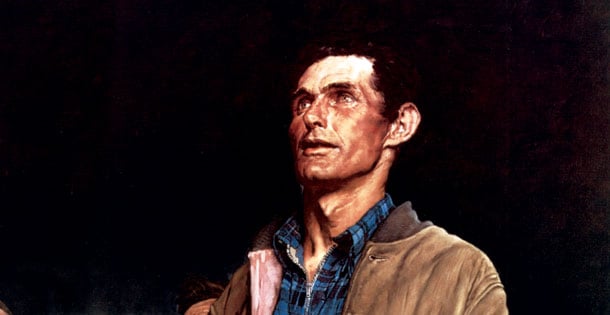

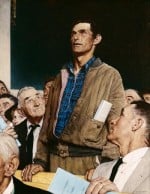

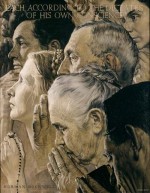

Inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous “Four Freedoms” speech delivered to Congress on the eve of World War II, Norman Rockwell created four paintings depicting simple family scenes, illustrating freedoms Americans often take for granted.

Rockwell spent six months painting the Four Freedoms, which were published in a series of Saturday Evening Post issues in 1943, accompanied by short essays from four distinguished writers. The U.S. government subsequently issued posters of Rockwell’s paintings in a highly successful war bond campaign that raised more than $132 million for the war effort. Rockwell’s homey depictions of Roosevelt’s abstract concepts were widely popular across America, yet not everyone was completely in tune with the ideas elaborated in Roosevelt’s speech.

In an editorial published later in 1943 (reprinted below), Post editors addressed a controversy over the meaning of the freedoms, in a debate that still has relevance today. Is the dream still alive? As then, we are certainly permitted to hope and aspire to the same ideal today.

The Four Freedoms Are an Ideal

For millions of people throughout the world the Four Freedoms have come to represent something which gives meaning and importance to the sacrifices which the human race is now making, but these freedoms are by no means universally accepted as worthy aims for nations at war. Indeed, a not inconsiderable number of people regard the Four Freedoms as actually evil, an effort to deceive people into imagining that they will never again have to take thought for the morrow, since government will provide everything for them.

Few people object to the first two freedoms mentioned by President Roosevelt in his message of January 6, 1941. Freedoms of Speech and Religion are familiar to Americans and are already guaranteed to them. Some people wondered whether the President’s phrase “everywhere in the world” meant that the United States would be called on to fight until such liberties as we enjoy became the right of millions in Asia, Russia, and Eastern Europe. But what the President said was that we “look forward to a world” in which these freedoms are taken for granted. In as much as we Americans have prided ourselves on looking forward to such a free world ever since we became free ourselves, it is difficult to see that Mr. Roosevelt said anything very alarming when he led the world to hope that Freedoms of Speech and Religion might someday be the possession of men everywhere.

The real controversy, of course, rages about the other two freedoms: Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. The assumption by those who are alarmed at their inclusion in a body of doctrine is that they imply that men are to be guaranteed not merely against “want” in the literal sense, but against lacking anything they happen to desire at any given moment. Freedom from Fear, these critics affect to believe, implies that the Government is fraudulently promising to remove all the hazards of life which men have feared in the past.

If we believed that either Freedom from Want or Freedom from Fear meant that the New Deal was promising to pass a miracle which would end the necessity of individual work or foresight, reward the lazy and incompetent as richly as the able and conscientious, and set up a “welfare state,” we should be as dubious about the Four Freedoms as are some of our correspondents. Some New Dealers may misconstrue these freedoms, but there is little ground for such an interpretation. After all, “economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants” are as nearly realizable as “the full dinner pail” or “a chicken in every pot”— phrases seldom associated with radical welfare schemes. In fact, such understandings have been the professed goal of American statesmen for many years.

As to Freedom from Fear, it seems to us to contain no meaning more revolutionary than that suggested by Norman Rockwell’s touching artistic interpretation, in the picture of the parents regarding the untroubled sleep of their children. Mr. Roosevelt expressed Freedom from Fear as translatable into “a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point…that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor.” Nothing about guarantees against fear of measles, graying hair or the consequences of laziness or incompetence.

If there is genuine confusion about the meaning of the Four Freedoms, some of it is doubtless explained by failure to note that Mr. Roosevelt, in listing these objectives, used the expression, “we look forward to a world.” Well, so do the rest of us look forward to a world in which men shall respect the right of others to their own opinions; a world in which better use shall be made of the machinery of production, so that lack of necessities which are so easily produced shall be the lot of nobody who can and will contribute his labor; a world organized politically, so that men need not fear the horrors of destruction by weapons of war.

Few of us expect such a world to be attained all at once, by fiat of the executive or by mere use of phrases. But all of us are permitted to hope, in the midst of an unprecedently cruel and destructive war, that the peoples of the world will eventually understand their problems sufficiently to solve some of them. Thus interpreted, the Four Freedoms represent pretty well what men have always hoped for—political liberty, a better standard of living and an end to war. We should think all Americans could get together on such an expression of human aspiration.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I have the series of Norman Rockwell’s prints of The Four Freedoms, with accompanying texts on the same page.

How many sets of these prints were made? I would appreciate any information you may have available.

Thank you,

Elizabeth Killian

My mom Arlene Hess Bolster was his daughter. I couldn’t fix after I sent. Sorry.

My grandfather was the freedom of speech. Carl Hess. My mom Arlene Hess Bolster was his sister.

I have a freedom from fear print attached to the essay? Why? I can’t find another one anywhere. It is in original frame and about 2ft tall and 3 ft wide. No staples from the magazine. Wish I could have more info on it.

I remember these prints. And I find them as inspiring as ever. Nowadays freedom means everything from “nothin left to lose” to “greed …is good.” Pretty mean spirited “heck with you and the rest of the country as long as I get mine…” kinda stuff. What ever happened to bold leaders like FDR? What ever happened to “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself..”? The Four Freedoms? Instead we get the magnification of fear. Yes we can becomes a timid “no we can’t.” These prints remind of the greatness we once had. The bold vision we once possessed. Gone now. Kinda sad really. These prints bring it back for a time anyway.

Shilrey was in the four freedooms painting ,along with her brother BiLL. She is the girl with the pigtails and brother is next to her. She is now 72 and would like to know has the rights to the NormaN ROCKWELL PRINTS.

SHE WAS ALSO ON THE COVER OF THE POST IN1943. She believes the publishers name was Mead Schaffer. Is there any information you can provide to help her. her health is not great.

My great-grandfather was the subject Norman Rockwell used for the white-haired gentleman looking up. He died before my 1948 birth, but the resemblance of my grandfather in his old age to his dad was striking.

My cousin Toni in California has the original painting, according to my aunt.

It is fun knowing we have a bit of a family tie to this Americana, Rockwell and the Saturday Evening POST!