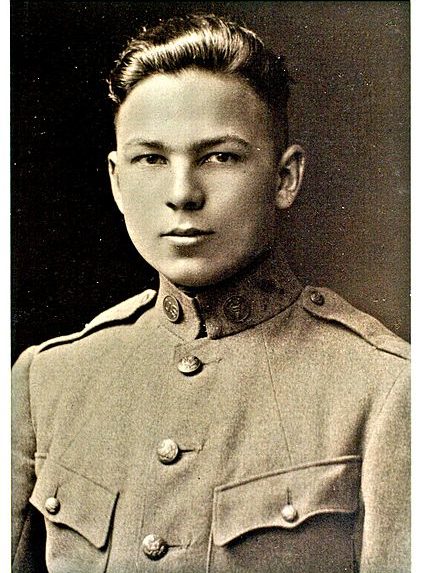

America lost a significant portion of its living memory on February 24, when Frank Buckles died. Mr. Buckles, who had recently celebrated his 110th birthday, was America’s last veteran of the First World War.

“Living memory” is the piece of history that reaches from the present moment back to the earliest memory of any living person. As long as Frank Buckles was among us, America had a link to the Great War and its entry into world politics. Now, that human connection is lost.

Admittedly, living memory isn’t as historically useful as documents and objective histories. Memories are personal, selective, and subject to fading and revision. But the idea of a bridge of memory spanning the 20th century give us the sense of a human connection to the distant past. And the past of Frank Buckles’ youth—on the other side of the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, and the digital age—seems particularly ancient to us.

Few events of that distant past seem as foreign as World War I. The motives and goals of the war are almost forgotten. Its weapons—barrage balloons, biplanes, and tanks that stumbled along at at 4 mph—seem quaint. The arch-foe, Kaiser Wilhelm II, looks like the comic villain from a silent movie. But the war was surprisingly modern in its use of machine guns, aerial bombing, torpedoing of passenger ships, chemical warfare, not to mention waging terrorism, executing hostages and running concentration camps.

Unfortunately, all of these weapons were applied with greater ruthlessness 20 years later, in World War II, which has become far more familiar to us, thanks to scores of popular histories, novels, and movies.

Frank Buckles didn’t want the First World War to fade into obscurity. Just last year, he was still actively campaign for a national monument in Washington to honor the 4.2 million Americans who served in World War I.

Gaining recognition for America’s role in the Great War has been a lengthy, uphill struggle. As long ago as 1958, the meaning and lessons of World War I were getting lost among America’s subsequent wars, as a Post editorial observed:

So much has happened since eleven A.M. on November 11, 1918, that many Americans have forgotten that Armistice Day was not originally proclaimed as a day in which to commemorate the dead who served in all American wars… On the contrary, Armistice Day began as a joyous, hysterical and in many places riotous shout of relief from all over the allied world, because one particular war was over. In Tennessee they call November eleventh “Victory Day,” which is closer to the original idea. The hideous four-year slaughter was over.

The victory, which was to have made the world “safe for democracy” and, in the view of even more imaginative individuals, to have made war forever impossible, has been disappointing.

The brains of the statesmen did not equal the sacrificial effort of the men in the trenches, in the air, and on the sea who had made the victory possible. For the moment, all that mattered was that we had “tied a can to the Kaiser,” and at long last the boys could come home.

All this was forty years ago, and the men who fought in that war are nearing their sixties or well into them. Younger people see them occasionally in convention assembled, driving around town in small locomotives or boxcars labeled “quarante hommes, ou huit chevaux‘” [40 men or 8 horses]— the big gag of World War I.

But the cause for which they fought and won is pretty well obscured by two later wars, one of which we described as a “police action,” and a bewildering series of crises imposed on us by our ex-allies, the Communists. Nevertheless, the victory of 1918 was important milestone in their history of the United States. For good or ill—but certainly inevitably—it precipitated this country into the stream of world affairs…

The finales of World War II and the affair in Korea were greeted by no such delirium as shook America twice in November 1918.

Now 15,000 marines are sent off to Lebanon with hardly a ripple of public excitement. Perhaps that is what happens when a nation becomes a “world power” loaded down with global responsibilities. Nevertheless on November eleventh, it is fitting to wonder whether world leadership can long succeed without some of the patriotic fervor which sent 2,000,000 Americans into a war overseas, and the bedlam of joy which welcomed them back.

History can’t preserve the past in its entirety; most of the details held in living memory will be lost to succeeding generations. But when America chooses which memories to preserve, it should give priority to those who served this country — and gave us the luxury to occasionally forget war and its cost.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Frank Woodruff Buckles is my name.

Died one hundred and ten years old.

The reason I have current fame

Is that I was the last, all told,

Surviving U.S. veteran

Who took up the proud Doughboy fight

To victory in World War I,

To pay the price for what was right.

The memories lack sight and sound.

There was no bearing witness press.

Some rally songs did come around.

I listened to them less and less.

After living the first World War,

I hoped that there would be no more.