From October 24-28, 1962, the world held its breath and waited for the news that the Soviet Union and the United States had launched nuclear weapons at each other. This was no media-manufactured event; the Cuban missile crisis had people glued to their television sets, crowding into churches, and pondering how they’d like to spend their last minutes on earth.

If Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev had not backed down from President Kennedy’s blockade of Cuba, the two countries would probably have launched their nuclear weaponry at each other—and half of you wouldn’t be alive to read this. (According to one study, the fatalities of a nuclear war in 1962 could have reached 100 million, more than half of the country’s population.)

For those not old enough to remember the Cuban missile crisis, it’s hard to believe how close the world came to Armageddon during those few tense days.

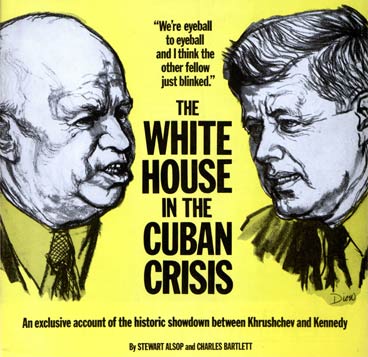

The entire crisis was covered in depth in a November 1962 Post article by Stewart Alsop and Charles Bartlett. The story, “In Time of Crisis” (December 18, 1962), recounts the long deliberations by Kennedy’s ExComm (Executive Committee of the National Security Council), which worked long, tense days from the start of the crisis to the first steps toward its resolution.

As the authors explained, when ExComm first learned the Soviets were building missile sites in Cuba, they weighed every option: invasion, bombing, and negotiation. Eventually they chose a strategy that was muscular enough to counter the perception that Kennedy was weak on foreign policy, but appeared reasonable enough to avoid immediate war. They would block Soviet ships from bringing the missiles to Cuba. “The option of destroying the missiles, and even of invading Cuba, would definitely be maintained,” Alsop and Bartlett wrote. “If the blockade did not cause Khrushchev to back down, then the missiles could and would be destroyed before they became operational.”

It was a risky move. The Soviet Union had a reputation for pushing its luck and rarely backing down. Very likely, it would consider the blockade reason enough to launch nuclear weapons toward America. Attorney General Robert Kennedy said, “We all agreed in the end that if the Russians were ready to go to nuclear war over Cuba, they were ready to go to nuclear war, and that was that. So we might as well have the showdown then as six months later.”

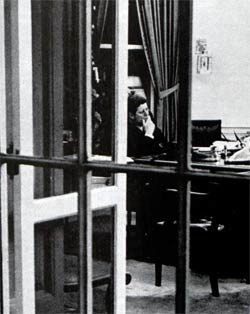

It might have been easy for Robert Kennedy to sound so certain a month after the crisis. At the time, the members of ExComm were anything but resigned to war. For five, nerve-wracking days, they sat with the president, trying out one idea after another, considering every possible move that would keep up the pressure without pushing the Russians too far.

In the end, to their unimaginable relief, Khrushchev backed down. He accepted a deal from Kennedy that would enable him to present the dismantling of the Cuban missile sites as a constructive move.

Alsop also recalls the evening after the crisis had passed that an elated and relieved John F. Kennedy chatted with his brother Robert. Savoring the moment of achieving peace, he was reminded of Abraham Lincoln’s brief enjoyment of victory between the end of the Civil War and his assassination. “Perhaps,” he quipped, “this is the night I should go to the theater.”

To read the full story, including the details of the weapons buildup and Khrushchev’s ultimate capitulation of the U.S., click here.

Also, check out our timeline of events—how the missile crisis started, and how President Kennedy brought it to a successful conclusion.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Nuclear chicken was the game.

U.S. missiles were in Turkey,

So Krushchev chose to do the same

With missiles in Cuba to be.

But Kennedy threatened nuke war.

Such grave threat made Krushchev rethink

This game too costly to play more,

And so the Soviets did blink.

Kennedy praised and Krushchev blamed,

Soon both of the leaders were gone.

The Cuban missile crisis named,

A close call but the world went on.

While blame against Krushchev was hurled,

Was he the one who saved the world?

This whole thing is absolutely mind boggling. I can’t imagine the stress the President and Bobby Kennedy were under. It had to have been incomprehensible to say the least.

What people had been fearing basically since the end of World War II was actually about to happen. In the end it didn’t, but came perilously close. The negotiations, persuasions and ulitimately the credit for preventing all-out annihilation must be given to President Kennedy. Just that alone ranks him up as one of our greatest Presidents ever.

This was my first memory of real fear as a child. Amazing to realize it was 50 years ago.