Maybe you have comforted a crying child by kissing her scraped knee to “make it all better”—and seen her tears turn to a smile and the pain recede. Perhaps you’ve stumbled to the medicine cabinet, half-asleep at 2 a.m., taken an acetaminophen for the headache that woke you, felt better—and discovered in the morning that you had actually taken a calcium pill.

Or maybe you took your arthritic knee to a hospital where you were prepped for arthroscopic surgery, wheeled into the operating room, and had a completely fake procedure in which the surgeon made a few incisions but did not remove the cartilage whose deterioration causes osteoarthritis—after which you had less pain and were walking better than you had in years.

Okay, you have probably never experienced the last one. But scores of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee did. They volunteered for one of the more astounding medical studies in recent years, in which researchers performed true arthroscopic surgery on some volunteers, flushing out the joint and removing cartilage, and sham surgery on others. The sham surgery is a form of placebo, an intervention that has no physical effect (inert sugar pills are the best-known placebos). In the groundbreaking study, when patients with osteoarthritis of the knee merely thought they had received arthroscopic surgery the intensity, frequency, and duration of their knee pain diminished as much as in patients who actually received the highly touted $5,000 procedure.

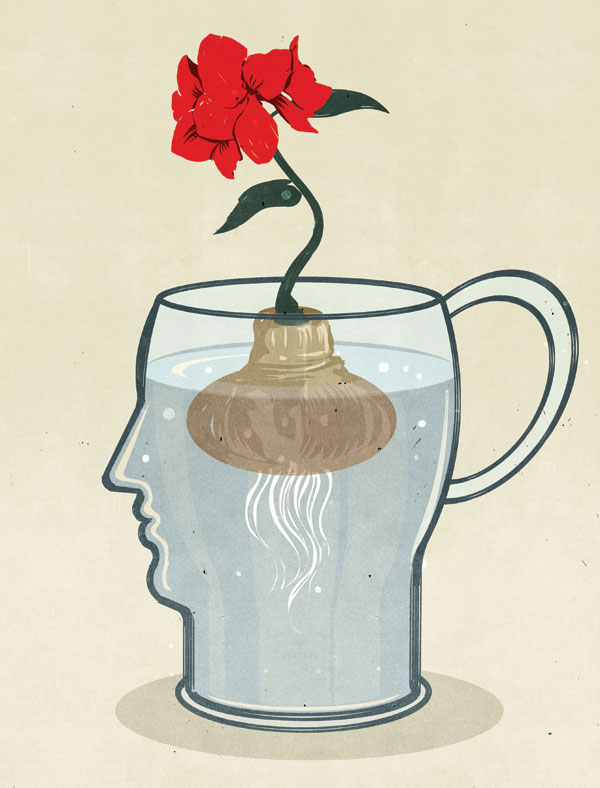

It is tempting to say that “mere thought” or “mere belief” caused these patients to feel and function better, just as the child’s trust in her mother made her knee feel better and our belief that little white pills will relieve a headache made the calcium tablet do so, even though it contained not a speck of headache-fighting medication. But if doctors and scientists have learned one thing about the placebo response or placebo effect, it is this: There is nothing “mere” about how thoughts, beliefs, and the power of the mind affect the body.

As researchers find more and more conditions that respond to placebos, they are gaining new respect for the power of mind. They are also learning how a belief or expectation can travel from the brain to arthritic knees, asthmatic airways, hypertensive blood vessels, and sites of pain. Understanding these mechanisms holds out the promise of tapping the placebo response more systematically, so more illnesses can be treated not with pills and operations (which almost always come with side effects or other risks) but with the power of the mind. “What we believe and expect can significantly influence the outcome of a disease, how much pain we feel, even whether Parkinson’s symptoms diminish,” says neuroscientist Mario Beauregard of the University of Montreal, who examines the brain basis for the placebo response in his 2012 book, Brain Wars.

To investigate placebos, scientists typically take patients with the same condition and give half of them a real treatment and the other half a placebo. Crucially, all the patients believe they are receiving the real treatment. Studies like these have shown that placebos can successfully treat pain and other problems, including angina, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, hypertension, gastric reflux, psoriasis, anxiety, and depression.

But while anecdotes are not science, it is stories of the placebo response that drive home its awesome power—much more so than reports in dry research papers. Placebos burst into the medical literature in 1955, with an article by Harvard Medical School anesthesiologist Henry Beecher, who had served as a medic in World War II. One day, when his field hospital was running out of morphine, a desperate Beecher had injected some of the suffering soldiers with a saline solution, assuring them that it would vanquish their pain. Miraculously, it did. With that, placebos had entered the medical mainstream as worthy of study and, increasingly, clinical use.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now