After 150 years, the Gettysburg Address remains one of the most powerful speeches ever delivered. It is also one of the most surprising. In just 270 words, a self-educated, frontier lawyer managed to convey a sense of national loss and give purpose to America’s civil war. He also produced as fine a work of prose as any American has ever created.

In 1959, historian Jacques Barzun invited Post readers to take a closer look at “Lincoln The Literary Genius.” If you only knew Lincoln from his Gettysburg speech, he wrote, you might get the impression of a man who sat down one day and wrote a masterpiece. But Lincoln had been working on his unique style for a lifetime before he spoke at the Gettysburg cemetery.

His talent with words seemed to come from nowhere. Certainly it wasn’t anything he learned; Lincoln’s formal education amounted to less than a year of instruction spread thinly across his youth. Learning all he could from borrowed books and stolen hours of reading, he left home and drifted between jobs, finally studying law and entering politics. It would have seemed like one more of Abe Lincoln’s poor career choices because, on the surface, he had little appeal. He was awkward, homely, ill-dressed, unkempt, and spoke with a high, nasal voice.

But his years of riding the court circuit in Illinois had taught him how to capture and hold the attention of strangers. He learned how to translate questions of law into simple, clear choices. He spoke in a comfortable, familiar style, which narrowed the emotional distance between himself and his audience. And when necessary, he could drop into joking talk, mimicking the drawl and twang spoken by Illinois farmers.

Lincoln learned to write standing up; that is, he developed his clear, powerful style while he honed his oral arguments for court. As a result, his writing and his speeches have a similar clarity and cadence. But Lincoln had a special genius for order and brevity, Barzun claimed; he presented his thoughts in the most convincing sequence using the least words. Barzun also stressed Lincoln’s gift for rhythm, illustrating it with a fragment from a lecture by Lincoln.

“There is a vague popular belief that lawyers are necessarily dishonest. I say vague, because, when we consider to what extent confidence and honors are reposed in and conferred upon lawyers by the people, it appears improbably that their impression of dishonesty is very distinct and vivid. Yet the impression is common, almost universal. Let no young man choosing the law for a calling for a moment yield to the popular belief—resolve to be honest at all events; and if in your own judgment you cannot be an honest lawyer, resolve to honest without being a lawyer.”

“The paragraph moves without a false step,” Barzun observed, “neither hurried nor drowsy; and by its movement, like one who leads another in the dance, it catches up our thought and swings it into willing compliance. The ear notes at the same time that none of the sounds grate or clash: The piece is sayable like a speech in a great play.”

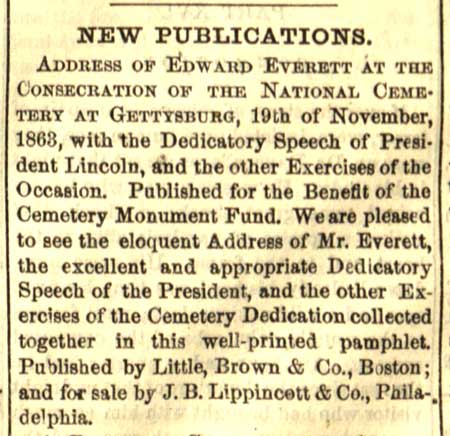

Lincoln never mastered the florid, wordy style that kept 19th Century audiences enraptured for hours. The admirers of fine oratory found Lincoln’s speaking style “flat, dull, lacking in taste,” Barzun wrote. When they came to the dedication ceremony at the Gettysburg cemetery, November 19, 1863, they were more interested in hearing the keynote speaker, Edward Everett.

The difference between Lincoln’s and Everett’s speeches that day illustrates the changes taking place in American thought and style. Lincoln spoke for two minutes. Everett spoke for two hours. Lincoln’s opening sentence, “Four score and seven years…,” was a concise statement of American principles. Everett began his speech with this windy fanfare:

“Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature. But the duty to which you have called me must be performed;–grant me, I pray you, your indulgence and your sympathy.”

In Everett’s defense, he knew what made a good speech. He wrote Lincoln on the following day, telling him, “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

The lean but powerful beauty of Lincoln’s prose impressed itself on Americans’ minds as generations of schoolchildren committed it to memory. It helped influence American writers to favor clarity over ornamentation. And its lean style, free of sentimentality and romanticism, brought a new honesty to the way Americans though about the Civil War.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now