© SEPS 2013

Entrepreneur and theme park magician Walt Disney was accustomed to difficulty; he’d overcome innumerable hurdles as he created his movies and his theme parks. But, as the upcoming movie Saving Mr. Banks (starring Tom Hanks and Emma Thompson) shows, he was unprepared for the challenge of working with P.L. Travers.

Disney should have known from the start that adapting Mary Poppins to the screen would be an uphill battle. He had already spent 20 years trying to buy the movie rights from Travers, the author of the popular children’s book. Travers resisted all offers until, on the brink of bankruptcy, she relented with great reluctance. She flew to Hollywood to consult with Disney, and that’s when the trouble began in earnest.

Travers didn’t like the music. She heartily disliked the animated penguins. She raised countless objections to the script, and even protested the use of the color red in the film. Nor did she approve of the casting; she suggested the male lead should not go to Dick Van Dyke, but to a British actor like Laurence Olivier or Richard Burton. Her objections continued all through the production. Disney didn’t even invite her to the premier for fear she would make a scene.

Travers’ biggest objection to the film was the way Disney portrayed Mary Poppins. In the movie, the magical nanny played by Julie Andrews is a sweet, gentle, and cheerful lady. In contrast, the character in Travers books was definitely not cheerful. Instead, as Travers’ biographer puts it, Mary Poppins was “tart and sharp, rude, plain and vain.”

Disney couldn’t have known that Travers was so protective of the character because she identified with her: “Mary Poppins is the story of my life,” she later told an interviewer. And Disney couldn’t have known the sad beginnings of Travers’ writing career; how Mary Poppins was born in the imagination of a destitute young girl living in a small town in Australia.

The year was 1913, and Pamela Travers’ alcoholic father, who had lost his job as a bank manager, had just died of influenza. Stricken by grief and sudden poverty, Travers’ mother left her children and attempted to drown herself.

Just seven years old, Travers found herself alone with her two younger sisters, listening to the monsoon rain drumming on the roof. Out of nowhere, the idea for a story came to her. She brought her sisters to the fire and there, as they huddled under a blanket, she spun them a story of a flying white horse whose hooves they could hear stamping on the tin roof above.

She also came up with stories about a magical nanny, giving her a name that she had found written into an old book: “M. Poppins.”

As a young woman, Travers began writing down her Poppins stories, and published her first book in 1934. Over the years, she added eight more titles to the series.

She also wrote adult non-fiction, including an article about her children’s books that appeared in the Post in 1964. In “Where Did She Come From? Why Did She Go?” she made no reference to her bleak girlhood, or the sad genesis of Mary Poppins. There is no hint of the woman who later told The New York Times, “Sorrow lies like a heartbeat behind everything I have written.” Nor is there any suggestion of the bitterness she was feeling about Disney’s version of her book.

In the Post article, Travers responded to the many fans who wondered how she came up with the idea for Mary Poppins. Travers never knew how to answer that question; she felt that her character had simply arrived, fully formed. It was easier, she wrote, to think that Mary Poppins had thought her up. “All I know is that without a word of explanation, a character…came in search of an author,” she added. “And the one she picked on, for whatever incomprehensible reason, was glad, surprised and grateful.”

But she acknowledged that the stories came from her life. For any writer, she believed, the material was always the author, “or the child hidden within her, perhaps, or the memories of her own youth, which are never far away.”

Consequently, her books always contained bits of autobiography. “Every story has something out of my own experience. Several record my dreary childhood penance of ‘going for a walk.’ But against that is set the blissful, forgiving moment at bedtime when I suddenly felt so very good.” In her books, she worked to recapture the sense of dread and delight that epitomized childhood for her.

Yet she insisted that she never wrote juvenile literature. “For me there is no such thing as a book for children. If it is true, it is true for everyone.” A writer, she believed, could never aim at a particular audience without becoming lost. Quoting Beatrix Potter, the author of Peter Rabbit, she stated, “I write to please myself. And so does everyone else.”

Travers felt that children wanted more than simple plots and happy endings—they were the ingredients put into children’s books to please adults. Children wanted stories that fit their experiences. Life, to them, was often confusing and frustrating, and they couldn’t be satisfied with tidy little tales. “What child enjoys being written down to?” she asked.

It’s interesting to speculate on what sort of movie Mary Poppins would be if Pamela Travers had been given creative control. Maybe she might have even secured Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton for the two leading roles. It would have been an unusual movie, but it wouldn’t have been as entertaining as the film Disney ultimately produced, which had removed so much of Travers’ original character.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Before I saying anything about this wonderful article, I have to state it’s GREAT having the comments back after being disabled since last December!!!

I knew there were problems only recently with Disney’s screen adaptation of Mary Poppins because of the new Tom Hanks film, but had NO idea to the depth and extent to which Walt Disney had problems with Ms. Travers, seemingly on most aspects, or that it they went back so many years before the film ever came out, which is literally one of the biggest miracles in film history.

It’s easy to make Travers a villian in the big picture, but this was her life. A creation that came out of terrible pain going back to her childhood, and there must be sympathy for her. If she had complete control over the film including casting, I don’t think it would have been the legendary, classic film it’s been since 1964.

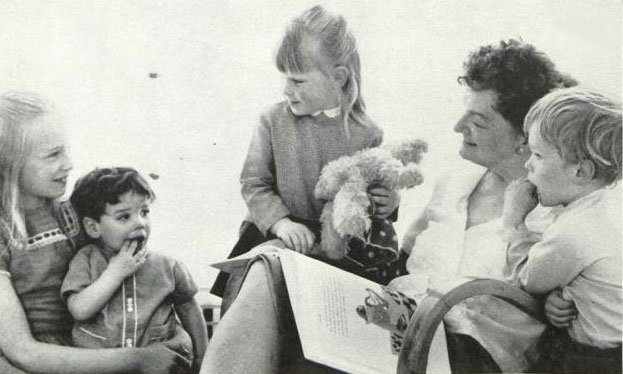

From looking at her picture above from 1964, I get the feeling she was a kind lady and enjoyed reading her stories aloud to children; these four look pretty enchanted to me, and she looks pretty happy herself. I’m glad.

Julie and Dick V. were perfect for this film, as were Liz and Dick for ‘Who’s Afraid of Virgina Woolf?” and “The Taming of the Shrew”. Thanks for this feature Jeff. I’ll get more out of the new Tom Hanks film because of it.