A recent Pew survey shows a growing division between Americans. Conservatives and liberals are increasingly separated by a political “chasm,” and hostility between the factions is rising.

At least one third of Americans on both the right and left wings believe their ideological opponents pose a “threat to the nation’s well-being.”

Troubling as this might be, we have seen far worse. Fifty years ago, the political divide in America involved more than media spin and postings on partisan websites.

In 1964, African Americans were struggling to win something closer to equal rights through demonstrations, marches, and bloc voting. On the other side of the racial divide, white political organizations in cities and states were opposing them through intimidation, legal obstruction, and violence.

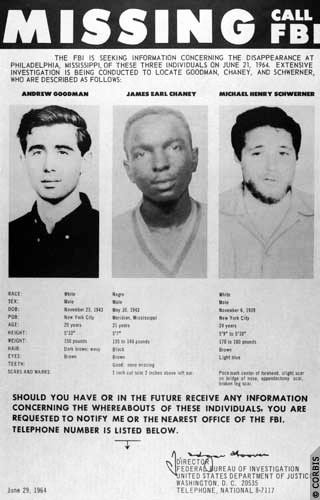

On June 21, the bitter contest reached a turning point when three civil rights workers–James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner–disappeared near Philadelphia, Mississippi.

It is significant that their disappearance–with no evidence of a crime—prompted a national outcry and a federal investigation, because it meant nobody believed civil rights workers just wandered off the map in central Mississippi in 1964. People rightly assumed they had been murdered.

Photo credit Lynn Pelham. © SEPS 1964

Their presumed deaths were another argument in favor of the recently passed Civil Rights Act. Surely, proponents argued, federal laws were needed to secure equal rights when local law enforcement appeared unable, or unwilling, to prevent such crimes.

The federal government had been intervening for years to prevent racial violence, but government efforts were often inconsistent.

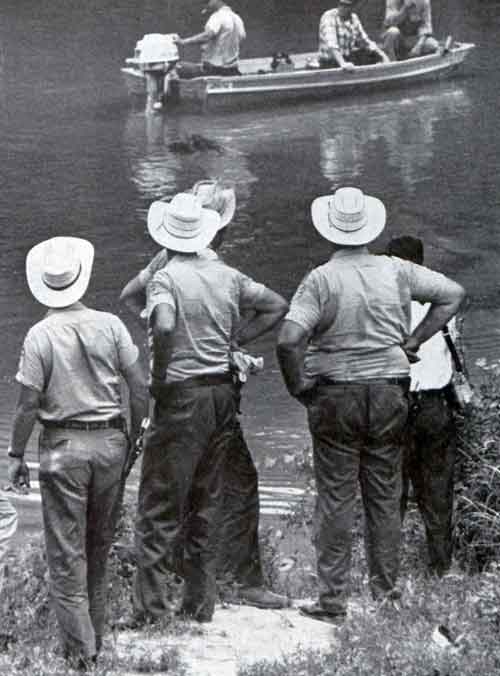

Under pressure from President Johnson, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent an agent into central Mississippi to investigate. Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent 150 federal agents.

Sailors from the nearby naval base in Meridian were ordered to help in the search. They began trudging through muddy swamps in Neshoba County and searching cotton fields for freshly turned earth.

But after a month of searching, they found nothing. Only when the FBI paid an informant $25,000 did agents learn the three men’s bodies had been bulldozed into an earthen dam at a local farm.

![“Robert Moses, 29, did most of the planning for this summer’s [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee voter registration] project. Raised in Harlem, he has a master’s degree from Harvard.” <br /> Photo credit Lynn Pelham. © SEPS 1964](https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/wp-content/uploads/satevepost/Moses1.jpg)

Photo credit Lynn Pelham. © SEPS 1964

In the Post’s July 25, 1964 issue, James Atwater interviewed a SNCC volunteer in Mississippi who told him, “I feel I would be willing to give up my life for this movement.” Another volunteer added, “I feel the same way, a willingness to give yourself to a cause that is really great, maybe the only great cause in America.”

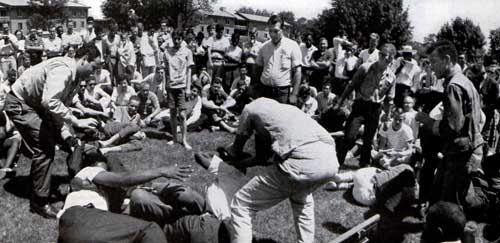

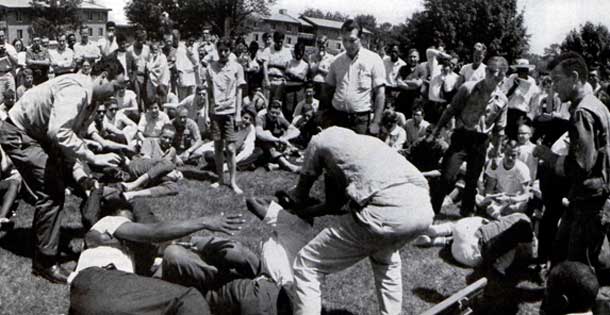

The men were not merely idealists. They had already met the hard edge of resistance. Recruited on college campuses to work in the Mississippi Summer Project, they were helping African Americans register to vote and learn reading and writing. And they were being beaten, shot at, and firebombed.

The students knew what awaited them if they met a lynch mob or, worse, hostile police officers. “When you go down those cold stairs at the police station,” said a SNCC volunteer, “you don’t know if you’re going to come back or not. You don’t know if you can take those licks without fighting back, because you might decide to fight back. It all depends on how you want to die.”

Photo credit Lynn Pelham. © SEPS 1964

After the bodies of the activists had been found, details of their murders emerged, which indicated far more planning than a simple lynching. The White Knights had specifically targeted Schwerner, who was working with members of the Mt. Zion Methodist Church in Longdale, MS. To draw him into a trap, Klan members attacked and beat members of the Mt. Zion congregation. On June 21, Schwerner, Goodman, and Cheney drove to Longdale to encourage the church members not to yield to intimidation.

When they left that afternoon, they avoided the lonely, backwoods road to Meridian and chose to take the highway through Philadelphia. Just as they entered town, Neshoba’s deputy sheriff Cecil Price stopped them for driving 65 mph in a 30 mph zone. He locked them in the county jail for seven hours without allowing them a phone call, and then released them on bail. The last he saw of them, he told the FBI, they had resumed their drive to Meridian.

Photo credit Lynn Pelham. © SEPS 1964

In fact, Price had used those hours to summon Klan members, who were waiting when Price raced after the blue station wagon and stopped it again just before it reached the county line. The Klansmen took the civil rights workers to a secluded area, shot them at close range, and disposed of the bodies.

Eventually, the FBI claimed 21 men were part of the conspiracy to murder Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. When the state of Mississippi refused to prosecute any of the men, the federal government charged 18 of the men with violating the victims’ civil rights.

Seven of the men were convicted, but none spent more than six years in jail.

Forty years after the killings, however, a group of white and black citizens of Philadelphia asked the state to reconsider the case. In 2005, state prosecutors charged Ray Killen with planning and directing the murders. He was convicted on three charges of manslaughter and is still in a Mississippi penitentiary.

Perhaps we exaggerate when we say the murder of Schwerner, Goodman, and Cheney marked a turning point in the dispute over civil rights in America. Such a term implies that matters improved afterward, or healing began between segregationists and integrationists. That simply did not happen. But, as with other bitter disputes in American history, extremists eventually committed an act that repelled the general American public, and cost them any chance of success.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The year was 1964.

Some places in the South were still

Fighting the U.S. Civil War,

In brutal ways as mad whites will.

A Mississippi murder case,

Three young civil rights workers dead,

Focused the nation, time and place,

On how mad white disease had spread,

Infecting local government

Into complicity with crime,

Encouraging mad whites, hell bent

Being racist in place and time.

In South and North there still exist

Mad whites bent on being racist.