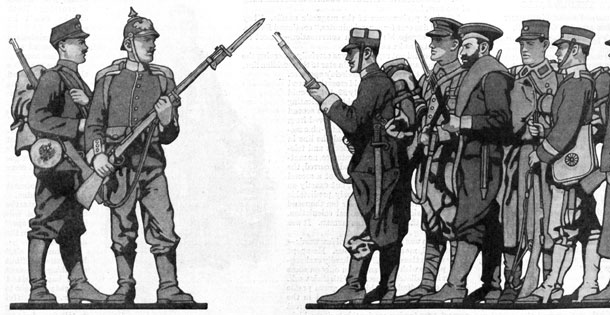

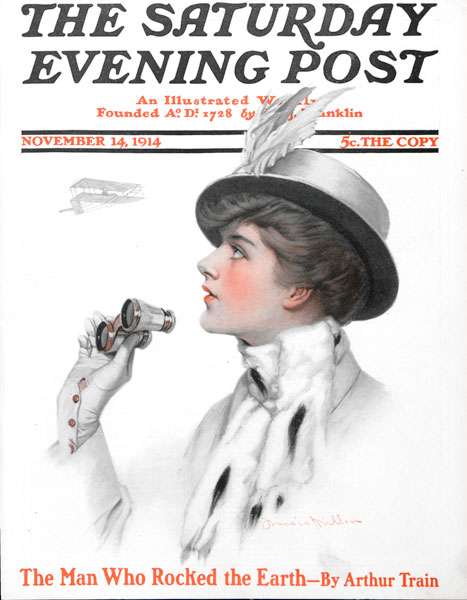

In the November 14, 1914, issue: Canada goes to war, Great Britain looks for a new theme song, and a journalist downplays the atrocities of a nation invaded.

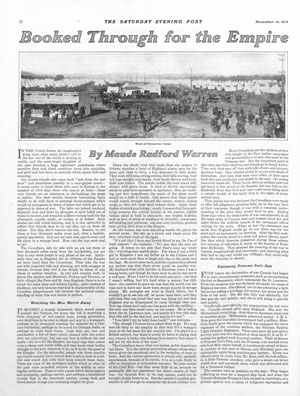

Booked Through for the Empire

By Maude Redford Warren

Over in Canada, the war enjoyed just as much support as in England, according to Warren. She wrote about the men she saw in an Ottawa parade of Canadian recruits. Their faces, she wrote, clearly showed“love for the Empire, the loyal urge that makes even a cheap soul worth while and that books their bodies through to the end, whatever it be, so it be for the good of the empire.”

But it wasn’t all flag-waving and happy parade. The author spoke with an elderly woman who had been walking alongside the recruits, among [whom/them] was her grandson. The woman spoke of the price she had paid to uphold the British Empire, and all the wars that were supposed to be the last.

“‘It seems to me now that that’s been my whole life — watching men march away. For when I was a little girl in Kingston I saw my father go to the Crimea and I had no more sense than to laugh and clap at the music and the flags. He never came back, and the comfort they offered my mother was that there never would be another war.

“‘My husband went with Gordon to Khartoum when I was a young bride, and though he came back to me he was never a well man. When I had to do his work and mine — not that I wasn’t willing, but it’s hard when a woman has children — the comfort he gave me was that the world was too wise now to have any more wars, except maybe in savage places.

“‘My youngest son went to South Africa, but I wouldn’t go to see him off; he never came back, and they said then that one proof that war was dying out was that England was so ill-prepared to carry through that one.

“Now my eldest son’s only son has gone with the artillery — the only one that could carry on our name. He is sailing down the St. Lawrence now, and maybe it’s true this time that this will be the last war, and maybe it’s not.’

“‘You didn’t try to hold them back?’ one ventures.

“‘No, though I’d never have asked them to go. If a man sees his duty to his country in that way it’s a woman’s place to do her share for the country too. I’m glad I’m a British subject, but there is surely no harm in saying that any woman is lucky who belongs to a country that doesn’t ask her for the lives of her men.’”

Vox Populi

By Samuel G. Blythe

The Briton spirit was just as determined and confident as the German, Blythe reported.

“There is no doubt that Great Britain is loyally and patriotically and unitedly in this enterprise, albeit there is a vast British population that does not yet appreciate the graveness of the dangers that threaten their land. Those who understand are loyal, and those who understand but partially are loyal also, so far as their understanding goes.

“‘This war,’ said [Home Secretary Reginald] McKenna, ‘was not of our seeking, but became our duty. Our case is clear, clean and perfect. It will be so held in the eyes of the world and so recorded in history. Therefore, we must win; and we shall win! There is no doubt of that.’

“‘We didn’t want to go to war,’ said the gardener at Sidcup, ‘but we had to go. Being Britons, we couldn’t do anything else. Now that we have gone to war, we’ll win!’

“Of all the men I talked to that Sunday afternoon there was not one who grumbled over the war, complained about it, bewailed his own hard luck — most of them had been hit one way or another — or expressed any but the most absolute conviction that Great Britain will win the war, and that the German Empire is to be eliminated. I did not find any whiners or any grumblers, or anything but a sort of stolid, philosophical view.”

One of the most discouraging war songs ever written appeared in Great Britain during these months. It was titled, “Your King and Country Need You!”

“This is sung nightly in every music hall and moving-picture show, and is more of a wail than an inciter to gallant deeds of arms.Here is the chorus, which is in slow march time, as the music says, and which the audience are invited to chant slowly with soloists:

“Oh, we don’t want to lose you, but we think you ought to go,

For your King and country both need you so.

We shall want you miss you; but with all our might and main,

We shall cheer you, thank you, kiss you, when you come back again.

“In order that the proprieties may be observed the author supplies a footnote, starred on the word kiss, which says: ‘When used by male voices substitute the word bless for kiss.’

Listen to “Your King and Country Need You!”, recorded by Helen Clark in 1914

Punitives Versus Primitives

By Irvin S. Cobb

Two weeks earlier, Cobb had brought up the topic of wartime atrocities: Germans slaughtering Belgians, and Belgians ambushing, poisoning, and torturing Germans. In this issue he reported on his investigation into the truth behind the rumors.

“From Belgian, from French, and from English sources I have had hundreds of tales of barbarities by Germans. From German sources I have had hundreds of tales of barbarities by Belgians, Russians, French and British — but particularly by Belgians. My deliberate personal opinion is that 80 percent of the stories are absolutely untrue.”

Cobb was, at the time of his writing, visiting the German side of the Western Front as a guest of the German army. For this reason, perhaps, he seems to have been quite sympathetic to their claims of innocence.

“I have found extended areas in Belgium through which hundreds of thousands of German soldiers had passed without signs of wanton damage of any sort — districts where the houses were all intact, the crops untrampled, and the fruit left hanging on the trees, and not so much as a window smashed or a haystack toppled over.”

He even seems to accept, with a regretful shrug, the Germans’ execution of a young Belgian woman. He heard the story from a German doctor in the border town of Aachen.

“During the investment and bombardment of the Liege defenses, a battery of German siege guns was mounted in the village of Dolhain. … From the accuracy with which shots from the Liege forts fell among them the Germans speedily became convinced that someone in the village was secretly communicating with the defending fortresses, telling the gunners there when a shell overshot the German lines or fell short. …

“A young girl, the daughter of a well-to-do citizen, was using a telephone that through some oversight the Germans had failed to destroy. From the window of her father’s house she watched the effect of the Belgian shells, and after each discharge she would call the fort in Liege and direct the batteries there how to aim the next time.

“For days she had been risking her life to do this service for her country. She was detected, tried by court-martial, convicted of violating the articles of warfare by giving aid to the enemy, and condemned to be shot. Next morning this girl, blindfolded and with her arms bound behind her, faced a firing squad. As I conceive it, no more heroic figure will be produced in this war than that Belgian girl, whose name the world may never know.

“‘I do not know how the American people will view the execution of military law on that brave young woman,’

said my informant. ‘I do know that the officers who tried her sorely regretted that, under their oaths to do their duty without being influenced by sentiment or by their natural sympathies, they sentenced her to death. They could do nothing else. She had been instrumental in causing the killing and wounding of many of our men. By the rules of war she had risked her life, and she lost it. Our troops … had no right and no power to spare the girl who, over the telephone, directed the fire of our enemies. But if I were a Belgian I would give my last cent to rear a monument to her memory.’”

Cobb never seems to think it outrageous that a young woman helping her country defend itself against an invading army should be executed as a spy or traitor. Yes, the monument idea was a nice touch, but it was a romantic gesture that saved no one’s life. There would be many more before the war ended.

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now