In December 5, 1914, issue: A senior British army officer predicts the war will last much longer than is anticipated, and a German officer shares the horrors of war.

An Interview with Lord Kitchener

By Irvin S. Cobb

Looking at the massive death toll of the First World War, it’s easy to believe the armies were led by incompetent, out-of-touch officers. In the British army, two officers have been picked out for heavy criticism: Field Marshal Douglas Haig and the man who preceded him, Horatio Herbert Kitchener. When historians speak of the British army of WWI as “lions led by donkeys,” they usually have Haig and Kitchener in mind. (You might recognize Kitchener’s face from “Your County Needs You.”)

In October of 1914, the Post correspondent became the first newspaperman to land a wartime interview with Britain’s top officer. Kitchener, as described by Cobb, comes across as both intelligent and farsighted, though Cobb comes across as more than a little dazzled by the field marshall. “From the dull-metal buttons to the arm-seam,” he wrote, “across the left breast of the coat, ran narrow twin lines of ribbon decorations … so numerous that it was of no use to try to count them. I know, because I tried.”

Kitchener began the interview by firing questions at Cobb, who had recently toured the German forces. Asked how the Germans justified their invasion of Belgium, Cobb told Kitchener the Germans initially regretted violating Belgian neutrality; later they began claiming Belgium was secretly allied to France. “In other words, Kitchener replied, “the Germans prepared their alibi after the act was committed — which weakens the alibi without excusing the act. It is a poor defense that must be changed in the middle of the trial.”

Kitchener has been faulted for several shortcomings: an inability to delegate, a lack of political savvy to hold his own in the British cabinet, his approval of Winston Churchill’s disastrous Gallipoli campaign. But Kitchener was smart and could be perceptive. He readily admitted the nature of war was changing. He also recognized, and planned for, a much longer war than many government officials expected. When Cobb asked how long the war would last, Kitchener replied, “Not less than three years. … It might last longer.”

“He said three years!” Cobb declared. “And at the time of speaking the war was a few days less than three months old. “Three months — the seas already empty of commerce and the lands of half the world shaking to the tread of marching millions who produce nothing and devour everything! … A year means half of Europe underground and the other half on crutches! Two years means a continent turned into a charnel house and a hemisphere ruined for a generation to come! … And the supreme head of the British forces had just said there would be three years of it, and perhaps more than three years of it!”

Four years, to be precise. Four years and four months.

War de Luxe

By Irvin S. Cobb

In his next report from the German lines, Cobb noted how the automobile and communication technology was changing the way soldiers fought wars:

“The day is done of the courier who rode horseback with orders in his belt. … And the day of the secret messenger who tried to creep through the hostile picket lines with cipher dispatches in his shoe, and was captured and ordered shot at sunrise, is gone too, except in Civil War melodramas. Modern military science has wiped them out along with most of the other picturesque fol-de-rols of the old game of war. Bands no longer play the forces into the fight — indeed I have seen no more bands afield with the lead-colored columns of the Germans than I might count on the fingers of my two hands; and flags, except on rare show-off occasions, do not float above the heads of the columns; and officers dress as nearly as possible like common soldiers; and the courier’s work is done with much less glamour but with infinitely greater dispatch and greater certainty by the telephone, and by the aeroplane man, and most of all by the air currents of the wireless equipment. We missed the gallant courier, but then the wireless was worth seeing too.

“Among the frowzy turnip tops two big dull-gray automobiles were stranded, like large hulks in a small green sea. Alongside them a devil’s darning-needle of a wireless mast stuck up, one hundred and odd feet, toward the sky. … From its needle-pointed tip, the messages caught out of the ether came down by wire conductors to the interior of one of the stalled automobiles and there were noted down. … The spitty snarl of the apparatus filled the air. … It made you think of a million gritty slate pencils squeaking over a million slates all together. We were permitted to take up the receivers and listen to a faint scratching sound that must have come from a long way off. Indeed the officer told us that it was a message from the enemy that we heard.”

One thing about war hadn’t changed though — the smell of the dead:

“A puff of wind, blowing to us … from across the battlefront, brought to our noses a certain smell which we all knew full well.

“‘You get it, I see,’ said the German officer who stood alongside me. ‘It comes from three miles off, but you can get it five miles distant when the wind is strong. That’ — and he waved his left arm toward it as though the stench had been a visible thing — ‘that explains why tobacco is so scarce with us among the staff back yonder in Laon. All the tobacco which can be spared is sent to the men in the front trenches. As long as they smoke and keep on smoking they can stand — that!’

“‘You see,’ he went on painstakingly, ‘the situation out there at Cerny is like this … the English held the ground first. We drove them back and they lost very heavily. In places their trenches were actually full of dead and dying men when we took those trenches. You could have buried them merely by filling up the trenches with earth.

“‘At once they rallied and forced us back, and now it was our turn to lose heavily. That was nearly three weeks ago, and since then the ground over which we fought has been debatable ground, lying between our lines and the enemy’s lines … literally carpeted with bodies of dead men. They weren’t all dead at first. For two days and nights our men in the earthworks heard the cries of those who still lived, and the sound of them almost drove them mad. There was no reaching the wounded, though, either from our lines or from the Allies’ lines. Those who tried to reach them were themselves killed. Now there are only dead out there — thousands of dead, I think. And they have been there 20 days. Once in a while a shell … falls into one of those trenches. Then — well, then, it is worse for those who serve in the front lines.’

“‘But in the name of God, man,’ I said, ‘why don’t they call a truce — both sides — and put that horror underground?’

“He shrugged his shoulders. ‘War is different now,’ he said. ‘Truces are not the fashion.’”

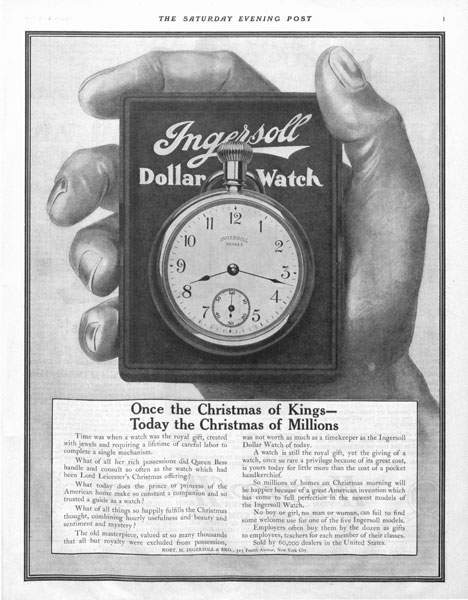

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post December 5, 1914 issue.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now