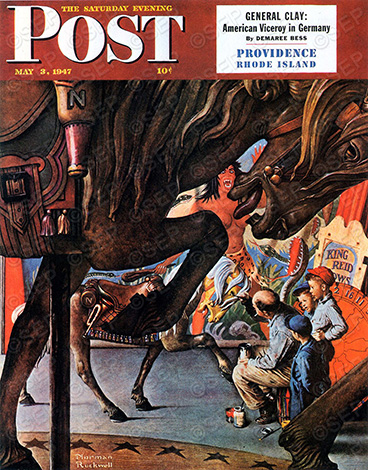

Norman Rockwell

May 3, 1947

Brown-tipped leaves hung between leaves clinging to their last shades of yellow and the sky was gray and flat, and the air metallic. Luc watched a squirrel flick its tail at the rust while his cereal sat untouched on the table behind him. He’d already dressed himself and for a second I missed the days when I could help him with that. His shirt was buttoned to the collar.

All summer, he’d begged me to take him to Coney Island. Now fall was almost over and still we hadn’t gone and I could tell he’d begun the slow process of letting hope go and turning against me. He was just like his mother in that way, holding so many small things against me.

“Change your clothes,” I said. “I’m not taking you to school.”

“Why not?”

“Because we’re going somewhere else.”

He turned back to the squirrel and it leapt away, landing on the nearest tree and running vertically down the trunk, leaves shaking in its wake. Luc wanted me to beg, but he wasn’t going to get what he wanted.

“You heard what I said, didn’t you?”

He nodded.

“Then don’t pretend like you didn’t.”

I watched him walk in sock feet down the hallway to change out of his uniform. Neither of us liked mornings. I think he learned from me how sensitive to be. Lately I’d noticed him smelling my coffee, which meant he was getting a taste for it, which was bad because he was already small for a 10-year-old.

Caffeine would stunt his growth and keep him from playing sports in middle school. Then again, maybe he wasn’t that kind of kid. I’d been made fun of when I was his age. Back then everyone just chalked it up to being boys.

I moved our bowls to the sink and rinsed them, holding my hands under the water to warm my fingers. Then I called the office and told them I was sick, and asked my coworker if he would process my orders this once, but I could tell he was busy. A wave of guilt rose in my chest and I decided to fill the smaller Thermos for Luc just for today. A little bit wouldn’t hurt him and he was old enough to practice moderation.

We packed sandwiches and took the scenic route down Beverley past the historic houses and the row of Hasidic houses where the little boy was murdered the year before. He was only eight and his body had been chopped into bits after a family friend went berserk, later claiming in court that inbreeding in the Hasidic community was to blame for his insanity. The boy’s feet were found in a freezer.

Winner

Runners-Up

Luc carried the Thermos by its handle and every hundred feet or so stopped to drink from it and let the steam warm his face. People passed us on the way to the train and I could tell Luc was feeling proud to be the only one of his friends not on his way to school that morning. After his fourth time stopping, I told him to drink slowly.

“If you drink fast, it’ll make you nervous.”

“I know.”

“Your mother liked coffee,” I said.

In the evenings, I’d walk around our apartment finding half-full cups with cigarette butts floating in them, which she’d forgotten during the day while she was writing, and she wrote everywhere. I’d leave them by the sink and wait for her to wash them herself, but after a few days they’d still be there, and I’d finally do them without saying anything about it, thinking erroneously that she had avoided doing them while knowing I couldn’t stand it, possibly to enrage me. It was one of the things we fought about in the end.

Our fights were circuitous and fruitless. I accused her of being avoidant and she accused me of being passive aggressive. I accused her of immaturity and she accused me of always trying to control her. I accused her of inconsideration and she accused me of manipulation and secrecy. Now it all seemed so stupid: just a lot of wasted words and wasted time.

“Last time we went to Coney Island, remember how the Wonder Wheel stopped at the top because that girl was sick?”

“That was scary, wasn’t it?”

He nodded.

We passed a cluster of Bangladeshi men conferring outside the fresh market and rounded the corner to the F train, descending a flight of concrete stairs covered in pigeon droppings and cooked rice, and receipts floating on the warm, rising air. In the station, Luc waited by the turnstiles while I refilled our MetroCards, and we continued on to the platform and stood near the benches. All the seats were taken.

We watched an older man stand and walk a few feet down the platform. A woman in heels took his place with her purse on her lap, scrolling through her iPhone. Her hair was tied at the back in a simple knot, from which some locks had come loose, and she wore a thin, gold band on her finger, but otherwise no jewelry. Her eyes were small and tired, staring down at the screen.

“Do you like any girls right now?” I asked.

“Not really.”

“Any guys?”

He looked at me. “No way.”

I looked back at him sideways and laughed. Luc didn’t think it was funny.

“Just asking.”

“I’m not like that.”

“I wouldn’t care if you were.”

He leaned forward to look down the tracks and I pulled on his hood to keep him from falling. A breeze floated into the station lifting a few strands of the woman’s hair from her suit jacket. All of us approached the doors as the train slowed to a stop, and we stepped into the cold, white light. Luc and I took a bench at the back of the last car. He stood to watch the tracks rush away behind us as we pulled south, entering the dark of the tunnel.

Even before Luc was born, we read to him every night. We stocked a bare-wood shelf with the books our parents read to us when we were little, and others we picked up at the bookstore around the corner. Quiet titles like Where the Wild Things Are and The Velveteen Rabbit were our favorites, including Luc’s. Even when he was too young to understand the stories, he’d lie down to listen to us read and play with his feet, always falling asleep before we got to the end.

There was something about The Velveteen Rabbit that got me every time: how loving a thing makes it real. But it doesn’t just stop with love, because when the rabbit becomes real, then it has to go away. The boy sees him again in the woods, at the end, and they look at each other before the rabbit disappears again. The boy’s life goes on as if the rabbit were never there.

And there is the fact that the rabbit has a body that can die, which he never had before. Only then can he be real.

On the train, Luc leaned against my shoulder, reading a horror novel.

“Is that scary?”

He nodded.

“What’s it about?”

He shrugged.

“You don’t know?”

“No, I know.”

Once, I caught him packing a book in his lunchbox, and when I asked him if he was really going to read it, he said, “I don’t know. I just want to have it with me.”

“Do you remember your mother’s favorite book?”

He shook his head.

“Me, either. If I thought really hard, I could remember.”

Luc closed his book in frustration and held it on his lap, glaring at the opposite wall.

“I’m sorry, you’re trying to read,” I said.

“It’s not that.”

“Then what?”

He stood and walked to the opposite benches, where two women in hijab leaned in opposite directions to let him look at the map. He placed his finger on a dot and traced it south to the water, wobbling as he turned around again and the train came to a stop. Then he sat back down next to me and looked straight ahead, as before.

“What did I say?”

“Nothing. You just talk about her a lot.”

I proposed to Luc’s mother on the Wonder Wheel when she was already Luc’s mother. She said no and we continued to ride in silence, the ground rising and falling beneath us, the car rocking back and forth in the air. Afterward, I went home alone. She called me that night to see if I wanted to talk about what happened, but I didn’t think there was anything more to say. She knew how I felt and I knew how she felt.

A few months later, we were living together. Luc was teething and sick all the time, and crying. We slept very little, and made love very little. I was jealous of the attention she gave Luc, as irrational as I knew that to be. She was a good mother, but more than that, she was a good human. She never allowed herself to be consumed by the role of motherhood.

She wrote just as often as before, but at different times of the day: early mornings, and while Luc was napping. Meanwhile, things like showering fell by the wayside. She never acknowledged my jealousy, though I knew she knew I felt it. She thought it was childish. She was right.

All of the rides were still as we approached from down the street, past our favorite pizza parlor, and the sky overcast as if it would rain, which meant that soon it would snow. Luc pulled my hand back in the direction of the pizza and we ordered two slices then continued on our way toward the water, eating them as we walked.

“I forgot they shut the rides down after Halloween,” I said. “I guess we’ll just play the games. I’m sorry.”

Luc didn’t respond.

“Are you disappointed?”

“No.”

“We can go to the freak show.”

“Sure, OK.”

He finished his pizza and threw the greasy plate in a trashcan as we crossed the road, entered the amusement park, and walked between the stalls. Cold air blew off the beach and the smell of salt mingled with that of hot dogs and axel grease, and fresh trash bags. The pathways were mostly empty save for a few older couples and families of tourists braving the cold, wet, late season.

From a distance, we heard a fuzzy recording of a bugle and a demented laugh, and made our way toward it. We found the building brightly painted in traditional circus posters and banana-yellow background, with loudspeakers shouting about the sideshow. A neon sign advertised “Freaks” and “Strange People.” I paid $15 and we took our seats before a low, red stage in an otherwise empty theater. Luc brought his knees up to his chest and rested his feet on the chair.

“You’re going to make it dirty,” I said.

He put his feet down. We waited.

People filed in and a few minutes later, a man in a black-and-white striped shirt took the stage. He carried a doll the size of his torso in one hand and a music stand decorated with gold fringe in the other. He placed the stand in the middle of the stage, rested the doll on it, and spoke into the microphone.

“Hello everyone, and welcome to the Coney Island sideshow. I’d like to introduce you to my friend Homer.”

“Homo, you idiot,” said the doll. People laughed.

“What?”

“Not Homer; Homo. My name is Homo. And you’re Limp!”

Luc laughed and brought his knees up again, resting his feet on the chair. I didn’t say anything.

“I’m Larry,” said the man in the striped shirt. “Not Limp.”

“That’s not what your wife told me,” said Homo. Uproarious laughter from the crowd. Luc looked at me. I smiled. He smiled and looked back at the stage.

“Homo, what’s this thing you’re wearing on your head?”

“It’s an Indian headdress. I’m Iroqueer.”

“Don’t you mean Iroqouis?”

“No, Iroqueer! I’m a gay Indian!” Laughs.

“And your sister?”

“Oh, she’s from New Mexico, she’s a Na-va-HOE.”

Luc laughed the loudest. I groaned and leaned back in my chair, covering my eyes. I glanced back at the door. A man stood in front of it with his arms crossed, leaning against the doorframe. He smirked at the stage. Luc noticed me looking.

“No, I want to stay,” he said.

“I think this might be too mature for you,” I said.

“No, it’s not! I can handle it!” he said. I motioned for him to lower his voice.

“I can handle it,” he said.

“Fine, but we’re talking afterward.”

He put his feet on the ground and sat up straight, to show me how adult he was.

“Homo, tell the audience about your childhood,” said Larry.

“My father carved me out of the hardest piece of oak in the forest,” he said. “Then he abandoned me. He was made of ASS-pen.”

We played some games afterward and Luc won a goldfish, which he promised to take care of. We bought ice cream and went to the boardwalk to eat it, and sat on a bench looking out at the gray water. Deep in the distance the horizon was blurred, and sea and sky churned together in the low-slung clouds. The air smelled ionic.

A woman jogged past us followed by a golden retriever on a leash tied to the woman’s waist. She kept her hair back with a headband that wrapped around her skull in a tight circle. Her leggings were the brown of the boardwalk with a silver stripe running from ankle to hip. I watched her until she disappeared into a cluster of people, then I couldn’t find her again.

“Remember The Velveteen Rabbit?” Luc said.

“Of course.”

“What happened to it?”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s not on my bookshelf.”

“You want to read it?”

“Yes.”

“You haven’t read that book for years.”

He got up and walked down the boardwalk and found a trashcan, then stopped and looked at me, holding the cone out over it. I nodded and he dropped it inside, apparently finished.

For a long time, we sat staring out at the water.

“Can I tell you something?” he said.

“Of course.”

“You promise you won’t be mad?”

“I promise.”

“I know you’re not my father.”

An artificial melody played in the distance, carried by wind. We were quiet for a long time.

“It’s OK,” he said. “I still feel like you are.”

“I’m glad. You know I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

“You are my son, though.”

“I know.”

I reached into my jacket and handed him one of the sandwiches we’d packed that morning, and opened the other for myself. Down on the beach, a couple walked along the line of the water, looking for shells in the sand. ![]()

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I definitely enjoyed reading your coming-of-age tale of a “father” and son rekindling their relationship. I really enjoyed the way you describe setting and place; it really cements the reader in this landscape of fun and revelation. The pacing was good and the characters were finely painted with delicate strokes of heartwarming honesty.