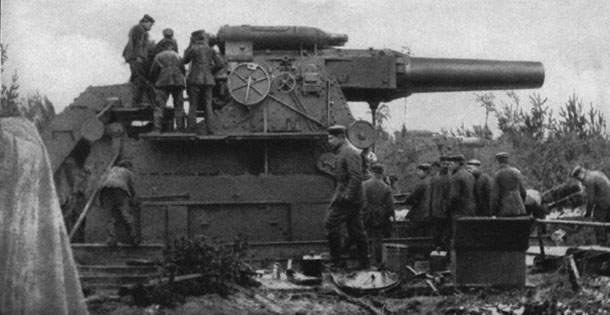

In the January 2, 1915, issue: Irvin S. Cobb predicts the end of walled forts as protection after witnessing the destructive power of the Krupp cannon.

In the Rut of War

By Irvin S. Cobb

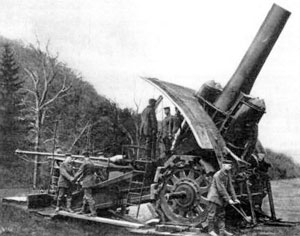

While the war was introducing new weaponry such as the airplane and poison gas, it was sweeping away some of the old standards of warfare. For centuries, the nations of Europe had relied on massive forts to defend their borders and cities. Their high, thick walls had long sheltered their armies and populations from enemy attacks. But the science of artillery changed that in 1915. Germany’s new cannon made raised fortifications obsolete.

Popularly called “Big Bertha,” the Krupp cannon (pictured at right) could level forts from a distance of 8 miles away. In his January 2 article “In the Rut of War,” Cobb reported his impressions upon seeing craters in Belgium that were made by the German weapon’s 42-centimeter shells:

“We were filled with astonishment, first, that [a shell], weighing upward of a ton, could be so constructed that it would penetrate thus far into firm and solid earth before it exploded; and, second, that it could make such a neat saucer of a hole when it did explode. Of the [displaced] earth … no sign remained. It was not heaped up about the lips of the funnel; it was not visibly scattered over the furrows of that truck field. So far as we might tell it was utterly gone.”

He had already learned that German artillery had destroyed the massive Belgian fort at Liege when he visited the remains of Fort de Loncin.

“I would have said it was some cosmic force, some convulsion of natural forces, and not an agency of human devisement that turned Fort Loncin inside out, and transformed it within a space of hours from a supposedly impregnable stronghold into a hodgepodge of complete and hideous ruination.”

Seeing this destructive power, Cobb felt confident predicting that “the day of the modern walled fort is over and done with.”

“I believe in future great wars … that the nations involved, instead of buttoning their frontiers down with great fortresses and ringing their principal cities about with circles of protecting works, will put their trust more and more in transportable cannon of a caliber and a projecting force greater than any yet built or planned.”

For the most part, he was correct. Most armies abandoned the use of forts after the war. France took a little longer to learn the lesson. It put its faith, and its army, inside elaborate defenses called the Maginot Line, which lined its border with Germany. It was meant to protect the country from any further German invasion. When the next war came, though, the Germans simply drove around it, entering France through Belgium and Luxembourg, where the Maginot Line was weakest.

Step into 1915 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post January 2, 1915 issue.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now