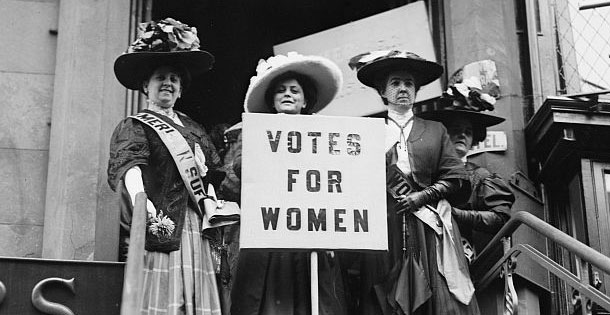

(Image courtesy of The Library of Congress)

The year was 1920 and U.S. politicians were worried.

Women had set aside their differences in income, education, and background to win the right to vote. They’d applied pressure to legislators and built support among the American public. Now, having achieved suffrage with the 19th Amendment, there was no telling what they might do next.

Some men feared women would take over the country’s political system. If women voted together, as a bloc, it would outweigh the male vote that was divided mainly between the Republican and Democratic parties.

To prevent women voters from creating a political party of their own, Republicans and Democrats began recruiting women. They also supported legislation on what we’d call “women’s issues.”

For example, Congress passed the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921 to help reduce maternal and newborn deaths. At the time, one in five infants died in their first year, and childbirth was the second leading cause of death for women. The new law provided federal funds to help states establish maternal and child health centers.

The bill was originally introduced by Jeanette Rankin, the first woman elected to Congress, but in 1921 it was voted down by 39 members, including the only woman holding a seat in Congress in 1921, Alice Mary Robertson.

It soon became apparent there would be no women’s bloc. Having won the right to vote, the women’s coalition broke apart. In subsequent elections, women’s voting patterns were nearly indistinguishable from men’s.

Realizing they didn’t need to pass targeted laws to obtain women’s votes, politicians ended the funding for the Sheppard-Towner Act in 1929.

In the following decades, women seemed to make little progress toward the equality suffragettes thought the vote would bring them.

In 1948, the grandniece of Susan B. Anthony looked back at what women had accomplished politically since women’s suffrage passed and was not impressed. As she concluded in her Post article, “We Women Throw Our Votes Away.”

“Women have frittered away our massive power at the polls,” Susan B. Anthony II wrote. “If we voted together on any issue … we probably could name the next president of the United States. … Our economic, political, and social position is only slightly better now than it was in 1920, when we got the all-powerful vote. The right to vote, in fact, is the only unqualified victory we have gained in a century.”

Because they wouldn’t cast a united vote for their rights, Anthony wrote, America’s women were barely represented in the government and in the workplace.

Much has happened since Anthony’s Post article. While women still don’t enjoy full, legal equality, there have been significant changes.

- “Women … form only one-fourth of all American workers,” Anthony wrote in 1948.

- According to the Department of Labor in 2010, 47 percent of America’s work force is female.

- “Women work at half the pay men get.”

- “About half of our hospitals don’t take women interns or let them hold staff positions.”

- “There are more than 50 men lawyers in the country for every woman lawyer.”

- “Only seven women sit in Congress today; men hold the 524 other seats.”

- In the 114th Congress, 104 of the 535 members are women; 84 women in the House of Representatives, and 20 in the Senate.

- “There are 7,500 state legislators in the United States, but fewer than 200 of them are women.”

- Nearly 1,800 women served in state legislatures (7,383 seats available).

There are several explanations for these changes. One would be a gradual shift in thinking about gender roles. For instance, many Americans began to rethink their ideas about women’s capabilities after seeing them take over men’s jobs during two world wars.

Another change was a shift in women’s voting. Beginning in 1952, Gallup polls noticed a 10 percent difference between men’s and women’s voting patterns in the presidential election.

Politicians realized they could no longer count on gathering women’s votes with the same appeal that worked for male voters. At least the presidential candidates would need to address women’s concerns.

The gender gap narrowed to 4 percent in 1992, but rose to 11 percent when Bill Clinton ran for re-election. By the 2012 election of President Obama, it had grown to 20 percent.

Today, women are not only becoming more independent in politics, they are also voting in greater numbers than men. But they are still a long way from flexing enough political muscle to obtain legal equality. American society can be highly resistant to change. Keep in mind that all the progress noted above took place over more than 60 years. And while the gender gap in pay continues to shrink, the change is coming at glacial speed. If it continues to narrow at today’s rate, it will take over 120 years before women earn equal pay for equal jobs.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now