News of the Week: The Dog Days of Summer, Delivery Drones, and Dating Dos and Don’ts

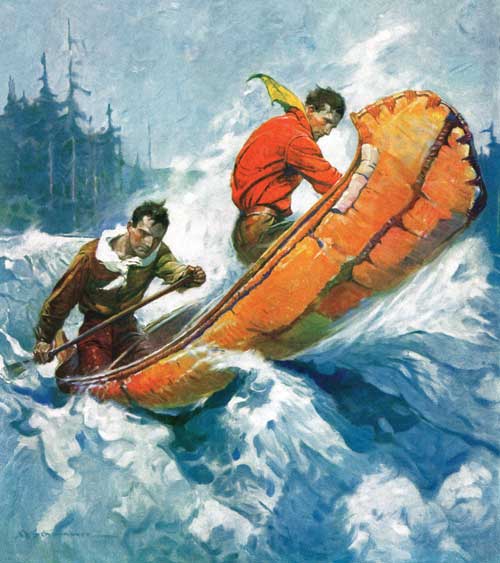

Thornton Utz

June 30, 1951

And It’s Not a Dry Heat

It’s 147 degrees where I live. Okay, that’s an exaggeration. It’s 91 degrees and humid. It only feels like 147.

These are “the dogs days of summer,” and the saying actually doesn’t have anything to do with dogs being lazy in July and August. It has to do with Sirius. That’s the dog star in the sky and not the satellite music channel. Though they once used a dog in their logo too. But I think it’s one of those sayings that changed over time and for all intents and purposes that’s what it means now.

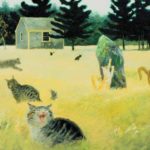

Here are some classic covers of The Saturday Evening Post that celebrate these summer days. My favorite is 1951’s Water Fight by Thornton Utz. There’s so much going on in that picture.

Knock Knock. Who’s There? Amazon. Amazon Who?

I don’t know if I ever want to open my front door and see a flying machine in front of it with my order from Amazon. How would that even work? Does a metal arm come out and ring your doorbell or knock on the door? Does a robotic voice call you on the phone and say “Hey, I’m outside!” or yell through an open window?

The company is testing drone delivery in Britain. Right now the tests, which aren’t allowed in the U.S., will be conducted under 400 feet, in rural and suburban areas.

These drones probably can’t deliver an 80-inch HDTV to you, but it might be great if you need socks.

Political Conventions on TV: A History

The Democrat and Republican conventions are officially over. We now return you to regular programming.

Atlas Obscura, a terrific site that explores the nooks and crannies of the world and its history, has an interesting piece about the first televised Democratic convention. It was in 1948 and it was the last one that didn’t have air conditioning (it was probably 147 degrees in there). And like this year’s Democratic convention, it was held in Philadelphia.

Goodbye VCRs!

I gave up my VCR years ago, which was probably an odd thing to do since I have many, many videotapes of TV shows that will probably never be on DVD or online (and I like the old commercials that are on the shows as well). I also don’t understand DVRs. They’re great and convenient, but more than once I’ll have a bunch of episodes of a TV show on them I want to catch up on and then my cable box will die, and I’ll have to give my cable company back the box, and I lose everything I’ve recorded. Is there an easy way to transfer stuff on my DVR to DVD or my computer?

After 40 years, VCRs are going away! Funai, the last company to make the devices, has announced that they will stop making them because not many people want them anymore and the parts are hard to get.

What’s interesting is that there were 750,000 VCRs sold last year, so somebody is still buying them. I’ll probably buy another at some point. Maybe they’ll become hip again, like vinyl records and flip phones and typewriters.

RIP Marni Nixon, Jack Davis, Richard Thompson, and Miss Cleo

Marni Nixon’s voice was known more than her name, even though you didn’t know she was singing. Does that sentence make sense? Nixon was the singing voice for various actresses in many movies over the years, including Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, Natalie Wood in West Side Story, and Deborah Kerr in The King and I. Her voice can also be heard in Cheaper By the Dozen, An Affair to Remember, Mulan, and other films. She passed away in New York City at the age of 86.

I didn’t realize that Nixon was the mother of Andrew Gold, who wrote and performed the hit song “Lonely Boy” and also wrote “Thank You for Being a Friend,” later used as the theme song to The Golden Girls. He died in 2011.

Jack Davis was one of the more influential pop culture artists of the 20th century. He was a cartoonist and illustrator and worked in many fields, from comic books and movie posters to album covers and magazines like TV Guide and Mad, where he was one of the founding artists in 1952. He was the last remaining EC Comics (Tales from the Crypt, etc.) artist. Davis passed away Wednesday at the age of 91.

Another cartoonist died this week too. Richard Thompson did the comic Cul de Sac until he had to retire because of Parkinson’s Disease in 2009. He was only 58.

Youree Dell Harris passed away this week too. You knew her better as Miss Cleo, the host of late night infomercials for The Psychic Readers Network. She died of cancer at 53.

Star Trek: Discovery

I know, I know, Star Trek posts two weeks in a row, but this is big news in Trekker-dom. At Comic-Con, CBS announced the name of the new series that will debut on the network’s streaming service All-Access in January (after the first episode is shown on CBS). The new show will be called Star Trek: Discovery (the U.S.S. Discovery is the name of the ship).

The show won’t follow the new timeline of the current big-screen movies, and executive producer Bryan Fuller says that each season of the show will focus on one story and won’t be episodic. Fuller also says the rumors going around that Discovery will take place before Star Trek: The Next Generation are false. No cast members have been announced yet.

Did You Miss Me?

Also coming in 2017 is season — or series, if you’re in England — four of Sherlock. Very excited. Here’s the trailer:

Smelly Apartments Are a Deal Breaker

One of my favorite episodes of Friends — it’s actually one of the greatest sitcom episodes, period — is “The One with the Dirty Girl.” Not only does it come in the middle of two of the show’s great story arcs (Chandler falling in love with Joey’s girlfriend; Monica and Phoebe doing their catering service), it’s also the episode where Ross dates a really attractive woman (Rebecca Romijn) and finds out she has a truly disgusting apartment, with garbage everywhere and rats running around. As the kids say, it’s LOL funny.

I thought of that episode when reading this list of the top dating dos and don’ts. The list comes from Wayfair, the home furnishing company that appears to have nine different jingles in their commercials. The thing that guys and girls equally hate the most about potential dates? Smelly apartments. Other deal breakers include grimy bathrooms, bad plumbing, poorly behaved pets, and lack of privacy.

Men and women also seem to hate ripped upholstery. Honestly, this is something I’ve never thought of when considering who I will date.

National Cheesecake Day

When I was a kid I hated cheesecake. Looking back it wasn’t because I didn’t like the taste. In fact, I don’t think I ever had cheesecake as a kid. It was more of a “Cheese? In a dessert?!?” type of attitude. But as an adult I learned to love it. Probably too much. But a lot of people love cheesecake too much. I mean, to keep up with demand there have been entire factories built just for their production.

Tomorrow is National Cheesecake Day. Here’s a recipe for chocolate chip cheesecake from Bake or Break, and here’s a classic no-bake version from Kraft that uses Philadelphia Cream Cheese. If it’s 147 degrees where you are, you might not want to turn on the oven.

A convention in Philadelphia and Philadelphia Cream Cheese. This was a theme week.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

I Want My MTV! (August 1, 1981)

Here’s the very first video that was broadcast on the network.

Germany and Russia go to war (August 1, 1914)

Is the Great War still relevant?

Iraq invasion of Kuwait (August 2, 1990)

After Iraq defied United Nations sanctions and orders, the United States and Coalition forces launched an attack on January16, 1991.

Ernie Pyle born (August 3, 1900)

The great war correspondent was born in Dana, Indiana, and was killed near Okinawa, Japan, in 1945.

First issue of The Saturday Evening Post published (August 4, 1821)

SEP Archives Director Jeff Nilsson takes a look at some of our earliest issues.

Marilyn Monroe dies (August 5, 1962)

Here’s a terrific profile of the actress by Pete Martin, from the May 5, 1956, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

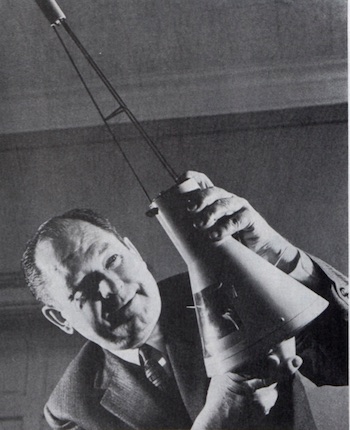

Our First Steps to the Stars

Humans could be landing on Mars as early as 2030 according to NASA administrator Charles Bolden. Which means that Americans who saw man first step on the moon may be alive to see a repeat event some 225 million miles away on the red planet.

When space exploration was still new, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration had to convince the nation that it would benefit from space exploration. In the 1959 Post article “Our Plans for Outer Space,” NASA’s first administrator argued for the fledgling space program and laid out plans for the first manned-spacecraft.

Our Plans for Outer Space

By T. Keith Glennan, NASA Administrator, as told to Robert Cahn

Excerpt from article originally published on February 2, 1959

Some people have asked, why all this urgency about a space program? There are several good reasons. The simplest is man’s basic curiosity. Throughout history he has attempted to get away from being earth-bound. He finally made it on a limited scale with the airplane. Now, for the first time, the advancements of science and technology have made it possible for him to take his first faltering steps toward the stars. …

Every week we get hundreds of letters with inquiries about manned space flight. Just the other day three boys in Oklahoma wrote, “… We would like to be on your first manned rocket to the moon, on the condition that you don’t send it in the next ten years. After that it will be O.K. because we will have finished college.”

While we can’t give encouragement to these Oklahoma youngsters, it is a fact that our present budget contains a project for a manned earth satellite. We call this effort Project Mercury, and the objective is to send a man into orbit around the earth and return him safely. …

No date has been set for this first manned-satellite operation. … We must establish adequate tracking and communications systems all over the world to monitor the orbit of our first man in space. We do not want to have him off in space without contact with our ground stations. We must be able to find him quickly if he lands in the jungle or the sea.

We will take no chances on Project Mercury. People may be killed in space exploration — many have lost their lives in aviation-flight testing. But no life will be lost because we tried to do something before we were ready.

In space exploration we are working with systems in which perfection is necessary. It is not like building a new airplane, where a pilot can test it and say, “Well, it doesn’t quite come up to maximum speed and is a little sluggish on the controls, but it is still a darned good air-plane.” For the highly complicated and difficult space missions, we have to expect that some developments will go slowly and some test vehicles will fail. We don’t like delays. But when pushing the state of the art so far and so fast, we have to operate on a flexible timetable to avoid disastrous failures. …

Once we have succeeded with Project Mercury and repeat manned orbital flights enough times to work out all the problems, it will be time to worry about journeys to the moon and the planets in our solar system. From our present viewpoint, manned exploration of the moon is dependent upon a technology not yet achieved. But we do have a long-range research-and-development program looking toward such a possibility.

Several items in our budget are vital to this long-range planning. Midcourse and terminal guidance systems to orient space vehicles is one research project. Developing improved tracking systems and better methods for transmitting and receiving data are others. We are also doing research toward launching into space laboratories themselves, which can be stabilized and used for experimental purposes. We are sponsoring a study of the systems and subsystems necessary for space rendezvous, where vehicles can be sent up to join satellites already in orbit. These space stations could be used for the assembly of large pieces of equipment — possibly nuclear reactors — needed in such really long-distance space travel as going to the far planets. …

The task ahead is not easy. It is going to cost a great deal of money. Our first year’s budget was $301,000,000, and for fiscal 1960 we will need nearly $500,000,000 to carry out our program. We hope and fully expect, however, that the long-range benefits in even the few practical applications we now foresee in weather forecasting and improved communications will far outweigh the costs.

I will not even try to predict when we will land a man on the moon. Nor will I try to predict what great things may be ahead for mankind resulting from our space exploration — although we already have learned enough not to be surprised at any possibility. I learned my lesson about crystal gazing more than thirty years ago when I was a young engineer installing sound-motion-picture equipment in theaters in the West. At that time, I made the bold prediction that there would never be a full-length all-talking motion picture. I don’t intend to repeat that kind of mistake.

Today, the benefits of space exploration and its refinement of satellite technology should be obvious to anyone using the Global Positioning System on their phones. Satellites are also tracking weather; relaying radio, TV, and telephone signals; and providing military surveillance. To see just how far NASA planned ahead, read Glennan’s entire article, “Our Plans for Outer Space.”

America Gets Weight Conscious

In the days of rotund President Taft, curvaceous Lillian Russell represented an ideal figure for women. “There was nothing wraithlike about Lillian Russell,” wrote Clarence Day in the Post, recalling Russell’s popularity. “She was a voluptuous beauty, and there was plenty of her to see. We liked that. Our tastes were not thin or ethereal. We liked flesh in the ’90s. It didn’t have to be bare, and it wasn’t, but it had to be there.”

Excess fat was regarded as a sign of beauty, maturity, prosperity, and even protection against wasting disease like tuberculosis. But in the new century, values were changing. The excerpt below is from an article that would have been many readers’ introduction to dieting.

Fear of Fat

By Margaretta Tuttle

Excerpt from article originally printed July 29, 1916

Twenty years ago, no man of 50 expected to have a waist and no woman of 40 a figure. If you looked pleasant and comfortable that was enough. You could wallow in fat and grow old in peace. … Nobody looked askance at you and said: “Why don’t you reduce?” Fat was fate, and no more to be helped than a crooked nose or big feet. …

These are the days of efficiency. … Fat has gone out with bonnets, and caps with lavender bows, and mufflers round the neck. … The fact is that we are eating more than we need, and working both brain and body less than we should, or we shouldn’t be fat.

You can’t get away from it. You may like to eat better than you do anything else, or you may think you need food ever so often to keep up your strength; but if you are fat you are eating more than you should or you are doing less than you ought, and both of these mean inefficiency. You cure yourself by eating less or doing more, or both; but it’s work and hard work either way.

The concept of healthy eating was so new when Tuttle wrote this article, she had to explain to readers what proteins and carbohydrates were. She also included a sample diet, which would probably not enjoy a doctor’s recommendation today. For more on 20th-century weight-loss, read the full text to Margaretta Tuttle’s “Fear of Fat.”

5-Minute Fitness: Yoga to Flex and Firm

Courtesy Acacia.tv

Strengthen leg, core, and arm muscles: “This pose opens the side of the body and brings flexibility to the spine,” says New York City and Acacia.tv yoga instructor Kristin McGee.

Reverse Warrior

1 Stand with right foot one leg’s length ahead of left foot, with right foot pointing straight ahead and left foot pointing to 10 o’clock as shown.

2 Bend right knee until it’s directly above ankle. (Be sure knee doesn’t roll inward.)

3 Pressing firmly into both feet, engage abdominals and stretch right arm overhead. (Keep torso squarely between hips.)

4 Lean back toward left leg, sliding left hand down calf. Look up to right hand. Work up to holding pose for 5 breaths. Come to standing. Repeat, other side.

Reps: 1 rep daily.

News of the Week: Star Trek 4, Retro Nintendo, and a Little Penuche (What the Heck Is Penuche?)

Beyond Star Trek Beyond

The third of J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek movies, Star Trek Beyond, hasn’t even hit theaters yet — it opens later today — but we’re already getting news about the fourth one. And this movie will be tied into events from the first.

In a press release this week, Abrams says that the fourth film will feature Chris Hemsworth as Kirk’s father. Hemsworth played the role in the first film in the series but only for what amounted to a cameo, as he quickly died. So it looks like this will be another time-travel adventure. I wonder if they’ll once again mess with the Trek timeline, maybe somehow putting it back to the way it was after changing it in the first film.

Abrams also says that the role of Chekov will not be recast in the fourth movie, following the death of Anton Yelchin.

Nintendo Goes Retro

I don’t play video games anymore, but if I did, I might buy something like this. It’s not the first game system of its type, but it comes with a lot of games and it’s pretty inexpensive. It’s the NES Classic Edition. It’s a mini-console that comes with 30 games already built in (no need for cartridges), including The Legend of Zelda, Donkey Kong, Galaga (which I was addicted to as a teen), Mario Bros., and Pac-Man. It will sell for $59.99 and will come out in November, just in time for Christmas.

Los Angeles: 1940s vs. 2016

The most recent video game I’ve played is L.A. Noire, a fun game that makes you a detective in 1940’s Los Angeles. It looks fantastic, with beautifully rendered cars and buildings. It’s the type of game where you don’t even have to play it. It’s a joy just to get into one of the cars and drive around.

I thought of the game after watching this video by Keven McAlester. It’s a 2016 retracing of a car trip someone made in the Bunker Hill section of Los Angeles in 1940. You get to watch the two videos side by side to see the changes (and there are many) to the area in the past 70 years. Bunker Hill was used in a lot of movies back then, especially film noir, but the city started a large redevelopment project in the area in 1959, which ended only a few years ago.

Confessions of a Republican, Part II

Remember back in March when I posted the video of the famous 1964 LBJ ad “Confessions of a Republican”? A lot of people thought that if you inserted the name “Trump” for “Goldwater,” it still works today. Well, it looks like Hillary Clinton’s campaign thought the same thing, as this week they released an update of the ad … with the same actor, William Bogert!

Oddly, I didn’t see this ad played at this week’s GOP convention in Cleveland.

RIP Garry Marshall and Norman Abbott

Garry Marshall passed away Tuesday at the age of 81. Before directing such movies as Pretty Woman, The Flamingo Kid, and The Princess Diaries, he was a writer/director/producer on a ton of classic shows, including The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Odd Couple, Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley, Mork & Mindy, The Lucy Show, and Make Room For Daddy. He acted in over 80 TV shows and movies, too. His sister is director and actress Penny Marshall.

The Washington Post has a list of careers that Marshall helped launch.

Norman Abbott was the nephew of comic Bud Abbott. After starting out as an actor, appearing in such films as the Abbott and Costello comedy Who Done It? and Walking My Baby Back Home, he became a top sitcom director. He directed many episodes of Leave It to Beaver, including the classic episode where Beaver falls into a giant bowl of soup, as well as The Jack Benny Program, Get Smart, McHale’s Navy, The Brady Bunch, Welcome Back, Kotter, Alice, The Munsters, and Sanford and Son. He was also a stage manager on I Love Lucy and the man behind the Broadway hit Sugar Babies. He served in World War II in the original Navy SEALs unit.

Abbott passed away at the age of 93 in Valencia, California.

How Did They Do That?

Last week I showed you a video of one of the finalists for the 2016 Illusion of the Year Award, and I promised that this week I’d tell you how it’s done.

The answer: It’s real magic!

Well, no. It’s actually simpler than that. There really is no “trick”; the shapes used look different depending on what angle you’re viewing them from. You can even see that if you pause the video when the shapes are turned around in front of the mirror.

Here’s a video that explains how it’s done:

Today Is National Penuche Day

Penuche is one of those foods that I’ve never heard of before but have eaten plenty of. Does that make sense? I mean I’ve eaten it but never knew what it was really called. I always just called it fudge, But penuche is lighter in color and made with brown sugar.

Here’s a recipe for penuche from Fearless Fresh. In fact, it’s two recipes. A new recipe was created for the site because the original didn’t set right. Both are included if you want to experiment and see which one works.

Or if you don’t want to bother making penuche, you could just buy some.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

Pioneer Day in Utah (July 24)

This official holiday celebrates the arrival of Brigham Young and his group of Mormon pioneers into Salt Lake Valley.

Discovery of Machu Picchu (July 24, 1911)

Archaeologists believe the mountain sanctuary was built for Incan emperor Pachacuti.

Mick Jagger born (July 25, 1943)

He may have been born during World War II, but he’s about to become a father again.

Sinking of the Andrea Doria (July 25, 1956)

The Italian passenger liner collided with the Stockholm near Nantucket, Massachusetts; 46 passengers and crew died.

United States Post Office established (July 26, 1775)

What became the United States Postal Service in 1970 has gone through financial problems in recent years, and the idea of stopping Saturday delivery is brought up every now and then.

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis born (July 28, 1929)

After the deaths of husbands John F. Kennedy and Aristotle Onassis, she became a respected editor at Viking Press and Doubleday.

Comfort

My 10-year-old nephew is skinny and has big ears. He admits to being timid about certain things — jumping off the raft into the lake, meeting new kids, hearing sudden noises. I too was afraid of things as a child — I like to think I understand David. I was delighted when his mother, my sister, asked me to take him to the circus. “Buy only one bag of popcorn,” she ordered.

“Is there anything we should avoid?”

“Yes, but you can’t avoid it. It’s the elephants’ parade around the ring.”

Oh, I remembered that circle of mournful pachyderms, plodding along until the crack of the master’s whip commands them to halt, to stand on their hind legs one animal by one, to place their front hooves on the hips of the poor guy in front of them, and then simultaneously to drop. Tail behind swings trunk in front. The act humiliates us all. David has read that the circus elephants are the most unhappy creatures in the universe. They’d rather be ripped open by a lion than make fools of themselves before a crowd. And so, when they start their act, his mother told me, David starts to cry. “Those big, big tears …”

“Is he scared of anything else?”

“If a clown boots another one across the ring, he winces. But he knows that the performers are padded. Those suffering elephants, though … Comfort him. Put your arms around him. Whisper into his ear.”

“Whisper what?”

“You’ll think of something.”

And so, eyes still dry, sharing popcorn, we watched the entire human and simian cast rush into the ring to a blare of trumpets. Then we watched the individual acts — the pyramids of acrobats, the monkeys from the Bolshoi, the famous clown who climbs the tallest pole and slips from noose to noose, hanging on by a finger, a knee, a nose. The clown raised laughter and gasps from the audience of children, and from their parents in puffy parkas, and from a group of oldsters in the row in front of us who had been hauled out of their Home for a treat, better than another afternoon of Bingo, I suppose. If the clown slipped, the net would catch him, although I have read that no net is ever to be trusted; it’s easy to fall wrong, and if you fall wrong you can break your silly neck. I would keep that information from David, I promised my schoolteacher self. I was the cool adult here.

Then jugglers threw their balls and dancers spun within hoops flung by other dancers. I waited for the elephants that would wring our hearts.

At last they came, each wearing a fez. If I were Turkish, I’d have been sorely affronted. The animals did their wretched parade. My arm slipped around my beloved nephew.

“Aunt Ella, they are so unhappy.”

“I believe they are. But some day this act will be outlawed.”

“Really?”

“Yes,” I hoped. “And the elephants will be returned to the savannah.”

“Georgia?”

“That’s Savannah capital S, a city in the United States. Our friends out there come from savannahs small s, grasslands in Africa. They’ll retire there and spend the rest of their long lives chomping green stuff and never having to grab a tail, only a banana.” I put my arms around him and whispered in his ear. “I love you,” I murmured.

And so he did not quite sob. He nestled closer to me.

The elephants were the last act of the first half of the show, and enduring their performance earned us another box of popcorn (I am not the most trustworthy escort).

The second half started with more clowns and then dogs jumping over each other.

The second half started with more clowns and then dogs jumping over each other. Next, a Cinderella ballet, mostly in the air.

My eyes wandered to the high corners of the big top. I could not make sense of the complication of guide lines, and pulleys, and ladders, and hooded lights turned this way and that, and cruel hooks dangling from ropes. While I was squinting at them, the high-wire funnymen appeared, riding small bicycles forward and backward across steel cables. And then came the high-wire acrobats, not at all funny, hurling each other from trapeze to trapeze, and then from person to person, one sequined performer hanging by his knees swinging another by her feet and letting go of her ankles a second too late, and she somersaulting through the air and then stretching out her hands to be caught, again at the wrong second, by someone on another trapeze. Only it was never the wrong second, it was the right second — how? In a flash, I remembered my childhood fears of falling, clawing at the air, smashing. My arm crept around David. “David!” I shamefully hissed. “A split second mistake could …”

“They don’t make mistakes. They practice and practice.”

Every time someone was in air, I buried my nose in his bony shoulder.

“He made it, Aunt Ella!” I heard.

And the next time …

“She made it!”

“Anyone could plunge,” I moaned.

“There’s a net,” he reassured me.

“It’s made of Kleenex,” I said. Where was my schoolteacher self?

“Oh, be quiet,” said an old man in front of us, and then put his head back and began to snore.

“There are wires at their waists, you just can’t quite see the wires,” said my nephew. “Or the ones at their wrists.”

I raised my head. Airborne twirls revealed no wires. “The wires are too narrow to see,” he explained. “The nets are strong. The performers know how to fall. Oh, dear Aunt Ella, I brought something for you,” and my magician of a relative withdrew from his pocket a red bandanna and lifted my head, which was now glued to his chest, and drew the cloth across my eyes as the stars of the show performed terrifying twists and somersaults and twists and somersaults combined … I had to guess what they were doing from the applause, which seemed to well up from the entire audience (excepting the one woman whose blindfolded head was now between her knees).

The applause rose again. Shrieks pierced our eardrums. But it was not the screaming that follows a disaster witnessed but one who pays tribute to disaster averted. I lifted my head from the vise of my knees and my eyes peeked above my bandanna. The stars were standing safely on their platforms, arms raised in triumph; and then, one by one, they swung themselves down on thick ropes and landed with a bounce on the safety net.

I untied the bandanna and held it in front of me as if I’d never met it before. “Well, well, well,” I said in a hearty voice.

David put his arms around me. “I love the circus,” he whispered into my ear. And then: “I love you, too.”

Getting Arrested at the Democratic National Convention

Hillary’s upcoming shindig is likely to seem sedate in comparison to the zaniness of last week’s spectacle in Cleveland. But, if anything, this is a turnaround from tradition. Historically, the Democrats have been the raucous ones.

Just look at the 1968 Chicago convention. For context, recall that President Lyndon Johnson, amidst abysmally low ratings due to the unpopularity of the Vietnam War, had announced in spring that he would not run for a second term. That decision opened up the Democratic field to JFK’s brother Robert Kennedy and antiwar candidate Eugene McCarthy, as well as the more centrist Hubert Humphrey, the incumbent vice president.

In the months before the convention, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. There was the palpable sense that America was coming apart at the seams. On the convention floor, the bitterness boiled over into shouting and shoving matches, but ultimately Humphrey and the status quo prevailed.

If this angered the antiwar delegates to the convention, it drove the 10,000 protesters outside into a pure and dangerous frenzy. Throughout the week, protesters were in open conflict with Chicago Mayor Daley’s security detail of 11,900 Chicago police — reinforced by more than 10,000 Army troops, National Guardsmen, and Secret Service agents.

Murray Kempton, a columnist for the New York Post and editor of The New Republic, was in Chicago to serve as a delegate for the liberal Senator Eugene McCarthy and also to write about the proceedings for the Post. After watching his candidate lose, he stepped outside to bear witness to the rioting in the streets, where he quickly found himself arrested along with hundreds of others.

The Decline and Fall of the Democratic Party

By Murray Kempton

Excerpted from an article originally published on November 2, 1968

We had arrived at 18th and Michigan, where the [national] guard and the police waited to say we could not go farther. The delegates had all found us and efficiently lined up behind Rev. Richard Neuhaus and me, since, for reasons obscure but connected with the failure of its beginning, ours was known as the Neuhaus-Kempton group. Such then was my last caucus; and, when Dick Gregory [the former comedian turned antiwar activist] went forward to get himself arrested and the Rev. Mr. Neuhaus to treat with the police, not knowing the procedure for getting arrested in Chicago as well as Gregory, I found myself stranded as its leader. Gregory’s blacks were juking in front of us; and [pacifist David] Dellinger’s strayed grays were no doubt preparing some manifestation behind us; and there fell upon me the sickening dread that at least two of our repertory companies were about to start their productions while ours, the amateur one, could not even think of its script.

Then Neuhaus returned at last, welcomed as no servant of the Lord often is, and said we should advance to confront the guard. There was nothing to do but get arrested, which took an unconscionably long time, during which we sat down symbolically, and then got up, because Gregory’s pards felt that it was about time to go into their performance and that we ought to stand and afford them free passage. A National Guard lieutenant colonel finally read his office over me, and I was moved, correctly but not cordially, into the wagon. Its bag was a mixed one of delegates and stray young people; riding over, the young called out “Free Vietnam” to the invisible streets outside. “Free assembly,” I ridiculously croaked.

In my usual job, you come to think of policemen as very much the same; when you are under arrest, they turn out to have quite extraordinary range. I should say that I met three nice cops for every nasty one; what surprised me was how far our permissive society has gone even with cops: A pleasant one feels free to be unusually pleasant and a mean one feels free to be unusually mean, neither of which tones is exactly what the book must command for treatment of that offender against society who is also its ward.

“Give me everything you’ve got with a sharp point,” the one who searched said. “One of you peace lovers put out an officer’s eye with a pin once. Do you know that?” He found a token that somebody had slipped me a long day ago and that I had put in my pocket without even looking at. It turned out to have the likeness of Martin Luther King on it; and he threw it to the floor. “Martin Luther Coon,” he said, grinding it with his shoe; “you all come from the same bag.” To my shame I did not make reply and only shuffled along, which is why it is so necessary never to be surprised. Yet, after this caricature, the trip to the Dark Tower, while tedious, had illogical moments of good manners. “What is a distinguished-looking man like you doing being arrested?” one of the booking detectives asked. I had no answer; the question, kindly meant, could only make me understand that I was getting old.

But, after a while, these desultory excursions into the study of policemen were driven away by the revelation of the other persons who had been arrested that night. The journey crept along in the company of The Professor of Physics at Stevens Institute and The Personnel Director of the Perth Amboy Hospital, The Telephone Company Lawyer, and then it would end in the waiting outside Riot Court, the Dark Tower itself, with the finding there of Harris Wofford, the President of A New York State University, of The Man from The New York Times, and The Rockefeller Man from Kentucky.

What could have brought them here in police custody? I knew why I was here; I had taken a contract. But what brought them, these safe men who had never before been arrested and probably never would be arrested again? It must be the indefinite suspension of their assurance of the virtue and redemption of America. The means of grace and the hope of glory had been taken away, because, after all, America had been their real God. And this night, otherwise inconsequential in our dreadful recent history, was The Night They Knew It.

But I could almost feel each of them, in his private heart, tending all afternoon toward this least dignified of places as the only one where they could be sure of being alone with their dignity. For them to have been in public that night would have been to rail or make bad jokes there; they had gone to the patrol wagon for privacy.

We stood about and talked among ourselves as men unused to arrest probably do; Dellinger’s stray young grays, who had been there before and would be again, slept on the floor. I felt quite tender about them, because I had noticed that although they sometimes carry signs bearing the device of some four-letter word or other when they are on-camera, they do not write dirty words on the walls of detention rooms. Do they, among other reasons, go to jail for privacy too?

There is very little to the rest. We went on talking; The Man from the Times came out from the Dark Tower and said this was a rough judge; he had been told to stop slouching. (I cherish The Man from the Times, but, in fairness to the judiciary, he does slouch.) My name was called; I entered the Dark Tower. And there, as usual with me, the first sight, instead of the Beast, was the warm bright greeting of William Fitts Ryan, my congressman; the convention was over and he had generously come down to be my lawyer. Bill Ryan unsheathed his congressional identification card and gave rein to his imagination for hyperbolic explanations of the distinction of his client; the judge struggled to the summit of whatever foothills of grace are afforded by night courts, and I was set loose.

For a complete inside look on the 1968 Democratic National Convention, read the full text to Murray Kempton’s “The Decline and Fall of the Democratic Party.”

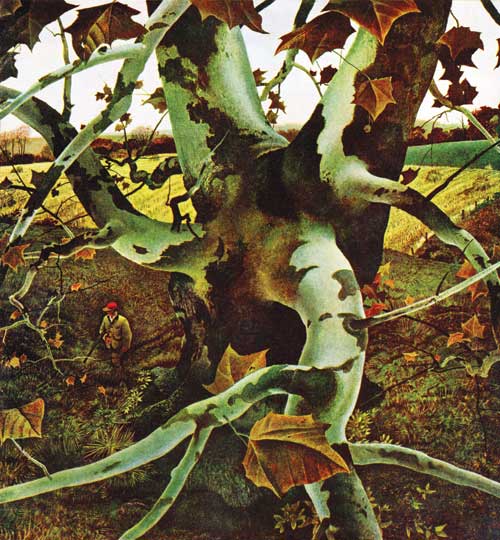

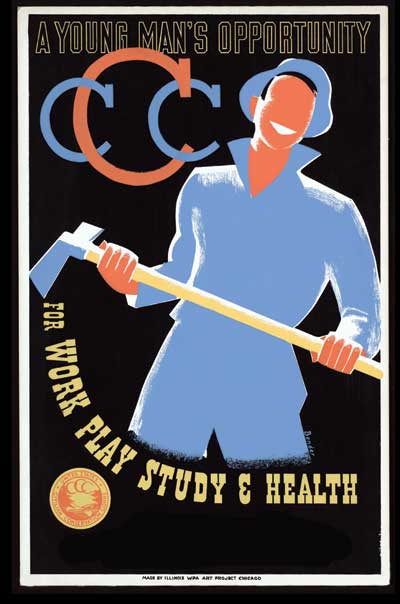

Gallery from the Archive: The Brandywine School

Art, American-style

In 1900, frustrated with formal art instruction, renowned illustrator Howard Pyle opened his own art school in the Brandywine Valley. Rather than teach technique, he encouraged students to capture a moment and bring it to life. His teachings would influence such greats as Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell.

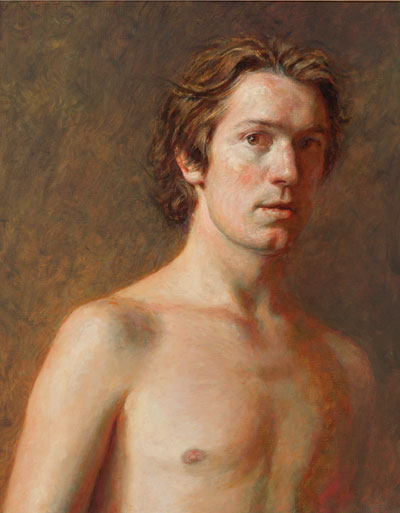

Andrew Wyeth

The Saturday Evening Post

October 16, 1943

The Wyeth Family

Pyle accepted only the most promising students. One of his most well-known was N.C. Wyeth, who enrolled in 1902 and who shared Pyle’s fascination with the landscape and history of America. Wyeth soon became a celebrity in his own right, painting several of the greatest early covers for the Post and, later, for The Country Gentleman. His work is known for its vibrant color and frequent high drama.

N.C. Wyeth

The Country Gentleman

June 1, 1944

N.C. Wyeth’s son Andrew, too, was inspired by the realism of the Brandywine School. But unlike his father, Andrew was a reserved and subtle artist who restricted himself to a limited color palette. Although he frequently painted landscapes like the one below, he described himself as an abstractionist.

Andrew Wyeth

The Country Gentleman

October 1, 1950

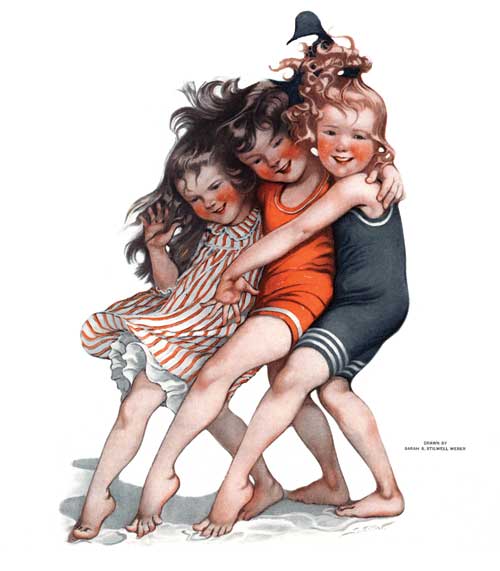

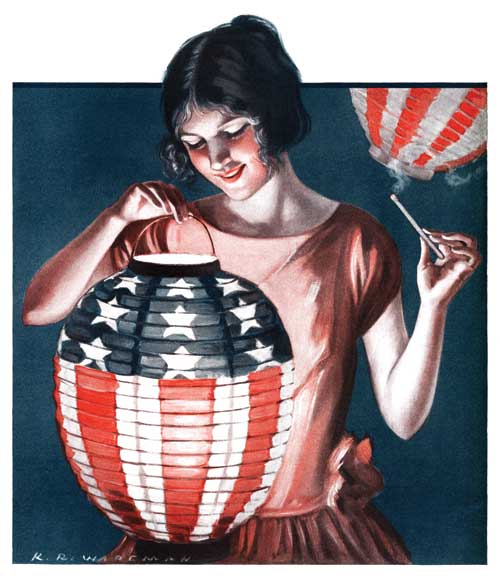

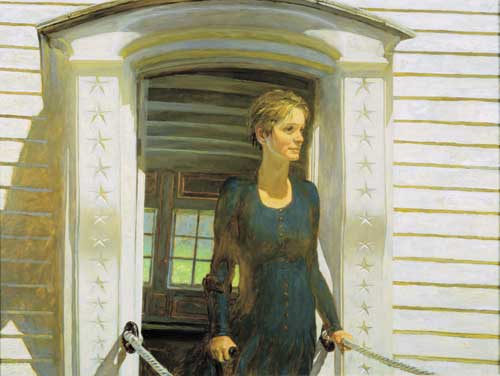

A Woman’s Place

In Pyle’s time, a career as an artist was not generally considered suitable for women. In a bold challenge to the art establishment, Pyle admitted as many women as men to his school. Several of his alumnae would become quite successful, including Sarah Stilwell-Weber and Katherine R. Wireman, both of whom contributed regularly to the Post.

Sarah Stilwel-Weber

The Saturday Evening Post

August 25, 1917

Katherine R. Wireman

The Saturday Evening Post

June 28, 1924

Down to the Sea

Anton Otto Fischer came to Brandywine after serving as a deckhand for three years. Under Pyle, he learned to apply his nautical experience to vivid seascapes like the one below.

Anton Otto Fischer

The Saturday Evening Post

September 20, 1930

Frank E. Schoonover’s early work was influenced by Pyle’s paintings of knights and pirates, but he soon developed his own style. He is remembered today for scenes of action and romance, frequently set in the wilderness.

Frank E. Schoonover

The Country Gentleman

March 1, 1930

Jamie Wyeth: Born to Paint

After the September 11 attacks, Jamie Wyeth was driving along the country roads — some as bumpy as washboards — in Pennsylvania’s pastoral Brandywine Valley when he saw a white barn with a huge American flag painted on it. The barn sat on top of a hill; a pond at the bottom of the hill reflected the stars and stripes. He immediately decided to paint it. He called this painting Patriot’s Barn.

“I had to record this stunning image,” he says. He goes on to call himself a diarist or recorder of everyday events and people. “I hate the idea of ‘now I’m creating a painting for an audience.’ My painting is simply recording my life and my thoughts, as if I were doing a diary.”

But if you look at the breadth of his work — from sketches to miniature mixed-media dioramas to children’s book illustrations to monumental landscapes to life-sized portraits — Jamie is much more than just a recorder. He is an expert painter of imposing realist paintings whose goal is to describe something authentic and American. “Whether I’m painting a person or a seagull or a pig, I like to think that if that pig painted, he’d paint himself exactly the way I was doing it. That’s what thrills me,” he says.

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth was born in 1946 with a silver paintbrush in his mouth as the third-generation champion for America’s first family of art — a family famous for distinctive and imaginative realism. Wyeth’s grandfather, Newell Convers Wyeth, better known as N.C. Wyeth, was an important illustrator whose swarthy, swashbuckling pirates, noble pilgrims, cowboys, and Indians embellished many children’s books — Treasure Island, The Last of the Mohicans, and The Yearling, to name a few. His very first sale (a cowboy riding a bronco) was for the cover of the February 21, 1903, issue of The Saturday Evening Post. N.C. was born in 1882 and died tragically in 1945 when his car stalled on the railroad tracks in the path of an oncoming freight train — just a few miles from his home near the village of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

Jamie’s father, Andrew (1917–2009), was world famous for painting stark, melancholy scenes depicting the hardscrabble life of farmers in rural Pennsylvania and fishermen in coastal Maine — people and places that seem worn down by time, the tides, and life’s worries. He worked in egg tempera — a medium dating back to the Middle Ages but not much in favor with 20th-century artists — to create his matte, mostly monochromatic, and often brooding images. He captured the same desolation seen in the lonely landscapes, Depression-era cityscapes, and isolated figures of painter Edward Hopper and that photographers Dorthea Lange, Diane Arbus, and Walker Evans captured on film.

Jamie Wyeth

Andrew’s loyalty to realism when every other artist in the world was going abstract marks him as both an iconoclast and a rebel in his time. Art critic Ray Mark Rinaldi notes, “No American painter was more skilled than [Andrew] Wyeth or possessed a greater ability to make marks with his artist’s tools, or with tempera paint, or pencil, or — and this is the revelation to most folks — watercolor.”

Jamie learned the family trade from his father and the basics of drawing from his aunt, Carolyn Wyeth (1909–1994), who, like her brother, learned painting at N.C.’s knee. “My grandfather’s studio was physically just up the hill from our house. It was left just as he left it,” Jamie says. “It was full of costumes and guns and all the other trappings of illustration. I would spend days upon days up there.”

“Both trained as if they were apprentices, Andrew to his father, N.C. Wyeth, and Jamie to both his father and his aunt Carolyn,” says Timothy Standring, Gates Foundation Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Denver Art Museum and curator of Wyeth: Andrew and Jamie in the Studio. While organizing this exhibition, Standring was given unprecedented access to the Wyeth archives and papers and could freely rummage through all the drawers of Jamie’s studios in Maine and Delaware, sometimes finding early sketches that Jamie had completely forgotten.

Jamie Wyeth started drawing when he was three and became a working artist when still quite young. “I had gone to public school like every other kid my age, but I was not interested in basketball or football. … I only wanted to paint,” he recalls. “My father was taken out of school because of illness when he was young. I thought that was a great pattern and determined that I was going to do the same thing,” he adds. His family agreed to let him leave school after the sixth grade, and that’s when he “seriously started painting.”

His father, Andrew, gave Jamie half the studio to work in. Jamie recalls that Andrew was a feverish worker who loved to play classical music loudly while he worked. Jamie preferred — and still does — working alone and in silence. “The only problem is that the record player was in my part of the studio, so I’d stuff my ears with wax.” Father and son painted together on many occasions, even modeling for each other. But were they pals or rivals? Jamie says that it was always a little bit of both.

Although their studio practices were different, they were similar in many ways. “Both used media in a highly unorthodox manner,” Standring says, noting that, even early in his career, Andrew blotted and smeared washes or scored through washes of ink with wire brushes or even his fingernails to get the desired effect. Similarly, Jamie often paints in mixed media — sometimes using watercolor, wash, and oil in a single painting. “I put paint in my mouth, on my fingers, on toothpicks, and often paint with the wrong end of the brush,” Jamie says. “I’m a terrible technician.” There was a period of time when he put his paintings into the oven because he wanted them to dry quickly, and when he wanted his paintings to dry slowly, he put oil of clove into the paint. “They smelled great,” he says, “but I think that Portrait of Lady took about a decade to dry completely.”

After a brief fling with egg tempera, Jamie chose to work mainly in oils, allowing him a broader and brighter palette than his father’s and bringing him into a direct line with his grandfather N.C. Wyeth, whose love of color and texture was legendary.

“But … like his father, he [Jamie] doesn’t want to paint under any fixed method or system, and instead treats each work individually as its images demand, which helps explain his obsessive search for new and interesting materials to experiment with,” Standring notes. “By allowing himself full rein with a multitude of media applied any which way, Jamie ultimately began to distinguish himself from Andrew.”

When he was just 17, Jamie painted Portrait of Shorty, an oil depicting a haggard, unshaven Chadds Ford neighbor wearing a dirty undershirt but sitting in what looks like a damask-covered antique wing chair. Jamie’s very first commission, the Portrait of Helen Taussig, was painted the same year. It was a commission from Johns Hopkins University, which wanted to honor Dr. Helen Brooke Taussig, a pioneer in pediatric cardiology. They could not afford Andrew Wyeth’s fee, but agreed when he recommended his son. Jamie recalls a gasp of horror from the assembled crowd when the flinty, intense portrait was unveiled. In fact, Johns Hopkins did not hang the portrait but gave it to Dr. Taussig, who wrapped it in a big towel and stuck it in her attic. “It is not a Betty Crocker portrait,” Jamie acknowledges.

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

But still, not an auspicious beginning to Jamie’s career, and in fact, he was quite devastated at the time and has done very few commissioned portraits since. It was a pleasant surprise when Johns Hopkins reached out to him recently to say that, after all these years, they were going to display the original portrait. But the mixed reaction to his portrayal of Helen Taussig was certainly a harbinger of the later reaction to portraits he did of Andy Warhol, which set off a tsunami of both praise and criticism in the art world.

“I work every day all day,” Jamie says. “I’m kind of a boring person because that’s all I do and that’s all I want to do. I don’t have any hobbies.” He goes on to say that painting does not require editors, sound people, lighting engineers, or an orchestra. “All you need is a stick with some hair on the end of it and sticky stuff called paint and a piece of cloth.” Jamie, by the way, paints with his father’s old paintbrushes because “they already made a lot of great paintings, so they know what to do,” he says with a smile.

“Although Jamie’s settings may look like the Brandywine Valley or Midcoast Maine of his father’s works, they are more a scenic backdrop for his quirky sensibility, which seeks out overlooked or peculiar objects, such as docking posts, plow blades, buzz saws, storage tanks, or sewer pipes,” Standring says. “One can look at his compositions as if they were repurposed accidental photographs; unintended compositions fraught with meaning,”

The subjects of Jamie Wyeth’s Pennsylvania paintings are agrarian — chickens, pigs, goats, horses, dogs, and barns — but freer and more humorous than those of his father. He also paints his wife Phyllis — a DuPont descendent and champion equestrian before she was disabled in an auto accident when she was in her 20s — standing in a doorway (Southern Light, opposite page) or capably at the reins of a carriage pulled by her Connemara ponies (And Then into the Deep Gorge and Connemara Four). In Maine, he paints lobster traps, circling gulls, white clapboard churches, weathered gray-shingled houses, and the lighthouse in which he lives (Tenants Harbor Light, aka Southern Island Light). “The sea has always attracted me,” he says, “and what’s more emblematic of the sea than to live in a lighthouse? It could be very cliché-ridden, but who cares … it is my home.

“My life is solitary. I’m alone on this island out at sea in Maine, but I don’t find it lonely,” Jamie says. “Here I am a mile offshore. I have to row back and forth, and that gives me focus in my work.”

He enjoys the solitary life when working. Sometimes, when painting outdoors on Monhegan Island, he sets up his easel inside an old, rank-smelling plywood fish-bait box (about the size of a refrigerator, with one side missing) to hide from tourists. “It is distracting when people talk to me while I’m painting,” he says. “When I’m inside the box, they can see that I don’t want to talk and, eventually, they go away.”

But when not painting, he’s quite welcoming to visitors, entertaining them with the stories behind his works. And every painting has one. For example, he painted Winter Pig (opposite page) in the dead of winter. In the midst of the project, he was called away. “When I returned, I discovered my model had eaten most of my pigments — some of which were very toxic,” he says. “For the next week, the farmer and I noticed that the pig was producing the most amazing rainbow-colored poop.” The 600-pounder survived the incident and stayed on as Jamie’s pet.

Jamie is always asked about Kleberg, the yellow lab with the black circle around his eye. “There’s a simple story,” he says. One day when Kleberg got too close to his easel, Jamie dipped his brush into black paint and put a circle around the dog’s eye. A few days later, a deliveryman remarked on the amazing marking on the dog — so did everyone who saw the dog. “Kleberg looked at me and I looked at him and we decided that the marking was here to stay,” he says. Eventually, he used mustache dye instead of black paint because the dye would last around a month. The dog seemed to enjoy the notoriety his marking gave him: “He would come to me when it needed to be redone,” Jamie says with a smile.

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

Although he demurs when you ask him about it, there is no doubt that Jamie Wyeth is the modern standard-bearer for the Brandywine School of art, founded by one of America’s foremost illustrators, Howard Pyle (1853–1911), who illustrated books by such luminaries as Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Pyle’s influence was rooted in his dissatisfaction with the confines of formal art education. His art school, set on the scenic banks of the Brandywine River, attracted such star pupils as Jamie’s grandfather N.C. Wyeth, Harvey Dunn, W.H.D. Koerner, Frank Schoonover, Jessie Willcox Smith, and Elizabeth Shippen Green. Pyle’s teaching was unique in that he rarely taught his students technique. Nor did he dictate what kind of paint or brushes to use. Instead, he taught what he referred to as “the pictorial idea” that an illustration should capture a powerful moment in time, a moment the viewer could comprehend in a single glance.

Pyle said that an illustration should make an impact and tell a dramatic story from a distance of 10 feet. He famously told his students: “Don’t make it necessary to ask questions about your picture. It’s utterly impossible for you to go to all the newsstands and explain your pictures.”

What became known as the Brandywine School of Illustration would influence many others at the turn of the 20th century and beyond, including Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell. Howard Pyle’s school was also famous for admitting women in equal numbers to men. Many of his students, including Sarah Stilwell-Weber and Kathleen Richardson Wireman, went on to illustrate covers for The Saturday Evening Post and numerous other magazines.

By the middle of the 20th century, realism (but, interestingly, not the Wyeths) fell out of favor, and illustration became a pejorative term in the art critic’s vocabulary. Abstract expressionism, minimalism, existentialism, pop art, and op art ruled the art world. “For years, you didn’t see art history or studio art students in the museum looking at illustration,” says James Duff, director emeritus of the Brandywine River Museum of Art. “About a dozen years ago, I became aware that professors were bringing their classes specifically to look at illustration … to look at Howard Pyle.” So, according to Duff, realism and illustration have come full circle. “If you live long enough, everything comes around again,” he says. Indeed, contemporary scholars and art critics are seeing Pyle’s influence in many spheres, from cartoonists Walt Disney and Charles Schulz to the current group of graphic-novel illustrators and beyond.

Jamie, too, has noticed that more and more young people are getting into making art and illustration, and he calls it an exciting profession. “I encourage art,” he says, “because you can work anywhere and with anything. Sometimes terrible messes come out of making art” — he admits to destroying half of what he creates — “but that’s okay, too.”

What is the Wyeth family’s place in the firmament of art today? Thomas Padon, director of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, summarizes: “Just as there’s a remarkable continuity in the three generations of Wyeth family artists in the sense of their shared creativity and abiding sense of place, there are interesting differences that set them apart in distinct ways. Taken together, their body of work is one of the major achievements in American art.”

Duff concurs: “N.C. Wyeth, Andrew Wyeth, and Jamie Wyeth are being increasingly recognized for their unique contributions to American art, and their importance will continue to grow through the decades with recognition of their amazing technical abilities, their perspectives on the human condition, and the sheer beauty of their accomplishments.”

Read our 2011 story about Jamie and his father and grandfather, “Wyeth Family Genius.”

News of the Week: Bad Emmy Noms, Brains on Facebook, and the Best Baked Beans in the World

And the Nominees Are …

Emmy nominations were announced yesterday morning. You can read the complete list of nominees here, but let’s talk about a few nods that stand out.

I don’t see how Cuba Gooding Jr. was nominated for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited Series or Movie for his portrayal of O.J. Simpson in The People v. O.J. Simpson. Talk about a miscast. But it was great to see Bryan Cranston nominated in the same category for playing LBJ in All The Way, and Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock Holmes in The Abominable Bride. Tom Hiddleston was nominated for The Night Manager. If he wins, maybe Taylor Swift will write a song about it after they break up, about how he cared more about the award than her.

The Outstanding Comedy Series category is a complete mystery to me. The Middle — the best comedy on television — wasn’t nominated yet again. Veep probably deserves to be there, but Modern Family for the 300th year in a row? Ahem.

It’s great to see Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee nominated for Outstanding Talk Variety Series, though we truly are in a different Emmy world now because that show is online-only. But I hope Seinfeld gets the award over Fallon, Kimmel, Corden, Maher, and Oliver. They’re fine, but CCC is truly something different.

The Emmy Awards will air September 18 at 7 p.m. ET on ABC.

Did anyone else find it odd that the nominations for the Emmys — the award that honors television — weren’t televised on television? They had a livestream online, but E! or one of the networks usually airs it. It’s true the nominees are announced later now — 8:30 a.m. PT instead of 5:30 a.m. — but one of the networks could have shown it, too.

This Is Your Brain. This Is Your Brain on Facebook. Any Questions?

I used Facebook a few times for around nine months total. I used Twitter every single day for eight years. I had to leave both of them for many, many reasons, and at the top of the list was that they were too much of a distraction. So I can believe the results of this study, which says that being addicted to Facebook isn’t that much different from being addicted to drugs.

Researchers at California State University-Fullerton published the findings in Psychological Reports: Disability and Trauma. They found that the brains of people who compulsively used Facebook showed the same brain patterns as people who used drugs and people addicted to gambling.

I bet a lot of people won’t pay any attention to studies like this, but you should think about it the next time Facebook is down and you go to Facebook to … post that Facebook is down, or go to Twitter to post that Facebook is down (or vice versa). If you use Facebook regularly, can you go even a few days without checking it?

Pokémon Go (No, Seriously, Please Go)

Sometimes a pop culture phenomenon comes along that completely takes me by surprise and confuses me. As I’m now in my 50s, I often think of what Danny Glover said in Lethal Weapon: “I’m too old for this &#*!”

The latest craze appears to be Pokémon. No, you haven’t traveled back in time to 1995; it’s something new, Pokémon Go, and it has apparently taken over the lives of everyone from the ages of 5 to 25. At least I hope that’s the cutoff age, because I don’t want to think about 47-year-olds walking around town with their smart phones, looking for various Pokémon (if that indeed is the plural — the name is short for the original Japanese name “Pocket Monsters”) that are hidden from view until you use that smartphone to see and “capture” them.

It sounds harmless enough, until you’re not watching where you’re going and you walk into another person or crash your car. Or you go to the 9/11 Memorial or Holocaust Museum to play your game. Both are official Poké Stops. And now I hope this is the last time I have to type Poké Stop.

Who Was D.B. Cooper?

Last week, the FBI officially closed one of the most famous hijacking cases in U.S. history, the D.B. Cooper case.

If you’re not familiar with the 1971 mystery, Cooper got $200,000 in ransom after hijacking a Northwest Orient plane to Seattle. He told everyone he had a bomb, and he then jumped out of the plane with a parachute and vanished forever. Cooper was never found — in fact, no one even knows if that was his real name — and a lot of investigators don’t even think someone could have survived the jump from a Boeing 727. In the past 45 years, none of the many tips have panned out (though a young boy did find a bunch of old $20 bills in 1980), so the FBI has decided to officially close the case. They say, however, that if any solid lead comes up, they’ll look into it.

One of the theories about the end of Mad Men was that Don Draper would turn out to be D.B. Cooper and vanish forever. It was a really goofy theory, but if you look at the artist’s sketch of Cooper, they do look a bit alike.

Is There Something Wrong with Lena Dunham?

If you’re at college and you eat sushi in the dining hall, you’re probably a terrible person.

That is apparently the opinion of Girls actress Lena Dunham, who says that serving sushi in the dining hall of her alma mater Oberlin (or any college or university) is “cultural appropriation.” It’s not only wrong that they’re serving things like sushi and banh mi, they’re serving bad sushi and banh mi, which is “disrespectful.” As The New York Post reports , Oberlin students protested because the sub-par versions of the ethnic foods served at the school disrespect the countries the foods are from and the people of those countries.

Sigh. I’m too old for this … well, you know.

Someone should tell Dunham that, in America, a lot of foods are “culturally appropriated.” I’ve had loads of bad pizza in my life, but I didn’t protest about how it was an insult to Italy (and I’m Italian). I’m not even sure the words “disrespectful” and “food” should appear in the same sentence. This whole thing is so stupid it’s almost painful.

By the way, Dunham also wants to remove guns from the subway ads for the action movie Jason Bourne. She wants you to deface the ads by actually ripping out the section where he’s holding a gun. (Note: please don’t do this.)

Maybe in the next movie, Bourne can attack the bad guys with culturally appropriated sushi instead.

The Ambiguous Cylinder Illusion

Can you guess the secret behind this finalist for the 2016 Best Illusion of the Year? It’s not special effects or an unfair trick, there really is something going on (and don’t read the YouTube comments, because that’s cheating):

I’ll have the answer next week.

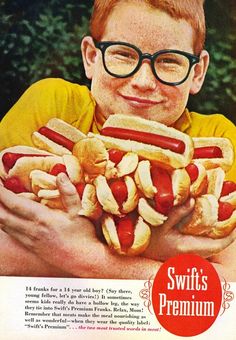

It’s National Baked Bean Month

July is National Hot Dog Month, and last week I told you about this year’s hot dog eating contest at Nathan’s. And what goes better with hot dogs than baked beans? July is National Baked Bean Month, too.

Here are two recipes for beans, one sober and one not-so-much. The first is Boston Baked Beans, because I’m from Boston and I get to pick the recipes that go here. It features molasses, brown sugar, bacon, ketchup, mustard, and Worcestershire sauce. And here’s a recipe from Epicurious for Drunken Beans. The “drunken” part comes from the bottle of beer you add.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

Joe DiMaggio’s streak ends (July 17, 1941)

The official Joe DiMaggio site has a multi-part podcast about his 56-game hitting streak.

Hunter S. Thompson born (July 18, 1937)

I wonder what the Gonzo journalist would think of this year’s election?

Bruce Lee dies (July 20, 1973)

Lee was in Hong Kong to have dinner with former James Bond George Lazenby when he collapsed from an acute cerebral edema caused by a reaction to medication.

Comic-Con opens (July 21)

Here’s the complete schedule for the San Diego pop culture convention.

Marshall McLuhan born (July 21, 1911)

The professor and philosopher who thought up the idea that “the medium is the message” also wrote a book a few years later called The Medium Is the Massage.

An Unobstructed View

Truth be told, Miriam was terrified of her grandson. When she looked at Mikie, she saw a shrunken version of her son. A brown cowlick sat straight up on his head like a pickaxe. The look of a serial killer flashed over his eyes when he was crossed. For Miriam, the pictures in her photo albums never aged. Life repeated itself in a continuous loop.

“It’ll only be for a weekend,” said Wendell. He didn’t have the nerve to lower the boom in person. Instead he phoned his mother at home.

“That’s, fine, Wendell, click, that’s fine.” It was 6 o’clock, dinnertime, the time of day when every taped political message, consumer survey and solicitor robo-called Miriam’s number. Miriam wistfully remembered when telephones were simple, when all your finger had to do was find the right hole and turn the dial. Now every conversation was punctuated by clicks.

“We’ll leave Miami Friday afternoon and be back Sunday click. Jolene’s making you a list. New York’s click just a phone call away. Heather and Glen click are down the street you remember Heather and Glen …”

Wendell and Jolene rarely left the boy. First her daughter-in-law nursed for two years. Then they spent the next two years trying to get Mikie to sleep in his own bed. The child was reading menus at restaurants but couldn’t cast his own shadow.

“We’ll be fine, Wendell. I can take click of a 4-year-old. We’ll be fine.”

“You’ve got to use call waiting, Mother! For the love of God use call waiting!”

Miriam pictured her son’s face reddening, exasperation working its way up from his starched shirt collar to his arched eyebrows. “You press FLASH,” boomed Wendell. “It’s that simple. You just click press FLASH.”

Miriam closed her eyes and kneaded the lids with her thumbs. “Add that to the list, Wendell. Add that to the list.”

The list was 10 pages by the time the weekend rolled around. Miriam arrived at Wendell’s home with an overnight suitcase in one hand and a sack filled with puzzles and toys in the other. Even though Miriam visited her son’s home each week, this was the first time she was asked to babysit overnight. Miriam wanted to meet the challenge head-on.

As usual, she had sought advice from her best friend. They ate at their usual lunch place at the usual time. The two elderly women sat face to face in a booth, bookended on each side by piles of sweaters, shopping bags, totes within totes.

“The child doesn’t like me,” said Miriam.

Sylvia was a breast cancer survivor. Her diet consisted of macrobiotic foods and the occasional pastrami sandwich. She Facebooked all of her grandchildren and prided herself on her computer savvy.

“Of course he likes you. It’s just that you’re a 33 and he’s a 45. Get with the program, Miriam.”

The past opened like a door. As if it were yesterday, Miriam pictured Wendell watching the black vinyl disc spin on the turntable, stepping first on one foot then the other, doing his own little dance. He especially loved those chipmunks, the ones with the high screechy voices.

“It’s all about Angry Birds,” said Sylvia, “and Power Rangers and Mutant Ninja Turtles. You can kiss Roy Rogers goodbye.”

Miriam blinked. There for an instant, for a fleeting moment, was Wendell’s arm sweeping the floor of his cowboys and Indians, his beloved fiefdom of plastic men.

“If it doesn’t have a battery,” said Sylvia, “if it doesn’t light up and make noise and give you a headache, don’t even bother.”

If Miriam expected to be greeted like Santa Claus, her fantasies were dispelled the moment she entered Wendell’s house. Her grandson thrust his head, neck, and elbows into the large plastic bag, rummaged around, and came up for air five seconds later.

“I don’t like dees toys,” said Mikie.

Miriam smiled. Then she craned her neck to the left and the right, listening. Wendell’s car had peeled out of the driveway. The coast was clear. Slowly she reached into her purse and retrieved the toy pistol.

“This was your grandfather’s,” said Miriam. “You feed the red paper in here and then you pull back the trigger …”

Mikie inched closer. He nestled Miriam like a cat, leaning into her body, clutching her blouse with his dimpled hands. “Can I touch it?” he whispered.

“Outside, on the sidewalk. This is an outside toy.”

They practiced for a full hour, aiming at the concrete. The air smelled like burnt toast. Wisps of smoke curled over their heads. Mikie jumped each time the gun snapped then just as quickly moved in for another try. Soon a parade of toys joined them. Star Wars stormtroopers, Buzz Lightyear, Wreck-it Ralph. With two hands clutching the gun, Mikie pointed the barrel and shot every toy figure dead.

Miriam looked to the left and to the right but not a single neighbor was in sight. She remembered streets filled with children, the ice cream truck drawing them like flies, mothers sitting on lawn chairs, fathers pulling up in driveways dressed in suits and ties. Like all of her memories, they were in black and white. Just like the television shows. Sometimes she couldn’t tell if the movies in her head were celluloid or real, the past blurred, the memories seeping like a sieve.

“It’s time to put the gun away,” said Miriam. She took Mikie’s hand and guided him inside the house. “We put it back in Grandma’s purse, and tomorrow we take it out again.”

He opened and closed his mouth like a small fish gasping for air. “But, I like it, Grandma. I really like it.” Again he leaned against her, his cheek rubbing against her leg.

“This is our little secret, sweetheart. The gun stays with me. When you come to my house, you can play with it there.”

She found Mikie’s favorite television channel and gave him a bowl of grapes to munch on. Then she grabbed both of his elbows and steered him towards the couch. “I’ll be right back,” she told him. “I have to warm up dinner.”

For three, maybe four minutes, her back was turned. The child was probably 15 feet away. If she pivoted counterclockwise at the sink, gazing over the counter and past the dinette set, she had an unobstructed view. Miriam put the frozen fish sticks in the microwave and pushed the buttons. For three, maybe four minutes, her back was turned. But when she glanced his way, the couch was empty.

The TV sang. Sunny days sweeping the clouds away.

“Mikie, sweetheart, dinner’s almost ready!”

On my way to where the air is sweet …

“Mikie! Mikie!” she yelled. “It’s time to wash up for supper.”

She sprinted into the den and ran her hand over the couch, as if the touching could magically summon her grandson’s bottom. It was still warm. In the middle of the cushion was a pancake-size depression, the soft weight of a child’s body pressing down.

She looked first in the downstairs bathroom, then in the living room. Next she opened the closet doors.

“Mikie!” her voice was louder now, a mix of irritation and fear. Fumbling at the locks, once twice three times pulling at the pegs, Miriam opened the sliding doors onto the patio. An uncle, it was Mortie or Bertie or Herbie, who could remember the name, had drowned at Coney Island. Her parents feared the water, were terrorized by the ocean, tucked her into bed with nightmare stories of people found beached on the sand like dead whales. The childproof fence was still intact. The water of the swimming pool clear.

She ran upstairs next, opening each door, checking under beds and behind curtains. Her heart pounded like a drumbeat. Mikie was nowhere to be found.

The gun! She must have been out of her mind to let him play with the gun! She flew downstairs and ran into the guest bedroom. There on the bureau was her purse. She poured the contents on the bed and shook it hard until every penny and pen rolled out. The toy pistol was gone.

She opened the front door slowly, whispering a little prayer as daylight inched in. Please God, let the child be there. Please God, let the child be on the sidewalk playing with the toy. She breathed in and out, prolonging the moment of knowing and not knowing, working up the courage to face the sun.

Her eyes swept the yard, the sidewalk, the neighbor’s yard to her left and to her right. There was no sign of her grandson.

Think, Miriam! Think! She ran inside and glanced at the list lying on the kitchen counter. There was a name. The name of a neighbor. But when she lifted the phone from its cradle, the touchpad looked foreign. It might as well have been written in Chinese with TALK and END in places where they shouldn’t have been and buttons, endless buttons that seemed totally irrelevant — why would anyone need so many buttons to make a simple call? She punched the numbers into the phone, but it wouldn’t ring. Instead she heard an electronic beeping, this house was filled with beeping, the doors beeped, computers beeped, appliances beeped, the beeping startling her and tormenting her like a finger poke in the ribs.

Miriam walked back into her bedroom, found her cell phone, and dialed 911. She could hear the blood pulsing through her ears.

“I’d like to report a missing child.”

They put her on hold. Beep. Can I help you?

“I’d like to report a missing child.” Miriam shouted into the phone as if the shouting would make them pay attention, would make them come faster, would bring the child who had disappeared back home.

How long has he been missing? someone asked.

She looked at her watch. “Maybe a half hour,” she said.

They put her on hold again.

“That doesn’t qualify as missing, you say?” Miriam paced the room, shouting. “Have you ever lost a child? Do you know what a half hour feels like when you’ve lost a child? It feels like an eternity,” said Miriam. “It feels like a lifetime.”

Suddenly the image of the Sears building in the Hollywood Mall flashed before her. More than 30 years back. She remembered when that little boy disappeared, the same age as Wendell. They had shopped in the store so many times, walking down the same aisles, the poor mother turning her back for a moment to look at a lamp. All it took was a moment.

Miriam hung up and dialed 911 again. “This is Miriam Lefkowitz and I’m having a heart attack,” she shouted. “3272 Andalusia. You better hurry.” Then she waited in front of the house.

Five minutes later a rescue truck pulled into the driveway. Miriam stood on the curb and waved her arms. Two people in uniform jumped out of the vehicle. A man and a woman.

“Is someone having a heart attack? We heard someone’s having a heart attack.”

“I was babysitting my 4-year-old grandson,” said Miriam. She pressed her palm to her chest. “It’s been 45 minutes. My hand to God if I don’t find that child I might as well be dead.”

“He probably ran to a friend’s house,” said the woman.

“I gave him a toy gun,” said Miriam. “He was playing with a gun.”

“The kind of gun that looks real?” asked the man.

Miriam squinted. Of course the gun didn’t look real. It was small and shiny and silver with a trail of red paper caps. What kind of an idiot would think that it was real? She smacked herself on the head.

The woman took to the street calling Mikie’s name as she made her way down the block. The man walked inside the house with Miriam. Hispanic. Tall. Beefy. Someone who couldn’t chase down a kidnapper but could easily tear him apart.

“Let’s look over the house one more time.”

Miriam nodded.

“If we don’t find him in five minutes, it’s time to call his parents.” The man looked over first one shoulder then the other. Then he stood up a little straighter and raised his voice. “Did you hear what I said, Miriam? IF WE DON’T FIND HIM IN FIVE MINUTES, HIS PARENTS WILL DEFINITELY FIND OUT.”

The man went to the kitchen and made a ruckus, opening and slamming the doors. Then he walked to the staircase, stomping his feet so hard the wood floors shook. “I’M WALKING UP THE STAIRS NOW, MIRIAM. I HATE WALKING UP STAIRS. WALKING UP STAIRS MAKES ME REALLY ANGRY. REALLY REALLY ANGRY.” When he got to the foot of the stairs, he stood like a statue and waited.

The sounds came from the powder room. The squeak of a cabinet hinge, the clink of metal falling onto tile. A roll of toilet paper unraveled down the hallway. Then a child’s voice.

“It’s me, Grandma!” Mikie rushed into his grandmother’s arms, buried his face into her lap, and started crying.

They ate their dinner of fish sticks cold and sipped their glasses of water. Miriam had never known such relief. She was too tired to be upset. She was too emptied to be mad.

Mikie finished his plate and licked his ice cream bowl clean. Then he sat and watched Miriam sip her tea. She took her time, swallowing hard, savoring each sip, willing her heartbeat to find a rhythm.

“Would you like to color with me?” asked Mikie.

“I’m not a very good artist,” said Miriam.

Mikie ran to get his crayons and a pad of drawing paper. He lay them on Miriam’s placemat, looked up at her and waited.

“Well, I do know one trick,” said Miriam. She took his water glass and traced the bottom.

“First you start with a circle,” said Miriam. Then she drew on whiskers, pointy ears, and a tail. “Now you have a cat.”

“More! More!” shouted Mikie.

She thought back and saw their kitchen in Brooklyn, the plastic peeling on the table, an icebox, a TV with rabbit ears. There was a child sitting at the table coloring. A little girl with skinned knees wearing an Annie Oakley hat. God, how she loved that hat.

“Now you have a dog,” said Miriam. “Now you have a rabbit.”

Mikie looked up. “Can I try?”

Together they traced the glass, her hand upon his. But this time when she pulled the glass away, the circle was broken. The crayon curved but one end didn’t meet the other. In seconds, Mikie’s face reddened and his lower lip shook.

“Let’s see what happens if we follow the line,” said Miriam. She took the crayon and continued the spiral toward its center. When she finished she added a small head with two tiny antennae. “Look what we’ve got now!”

“It’s a snail, Grandma! I made a snail!”

For the rest of the evening, until it was time for bed, they sat at the table and drew. Wendell and Jolene called. Sylvia checked in to make sure that Miriam was following the program.

“Couldn’t be better!” said Miriam. “We’re having a wonderful time.”

And when they woke up in the morning the kitchen was littered with papers. Spiral upon spiral. Coil upon coil. One unfinished circle after another. Their future lay before Miriam like a map. Clear. Unfettered and unencumbered. The Milky Way in the palm of her hand.

That Wild GOP: A History of Chaos at the Republican Convention

Anticipating fireworks at next week’s Republican convention? Think it’s going to be a huge shift from staid politics of the past now that Trump is leading the charge?

Turns out, those supposedly sober Republicans have a pretty raucous history. At the 1912 convention, barbed wire was secretly rigged under the bunting around the stage, presumably to keep Teddy Roosevelt’s rabble at bay. And, sure enough, TR stormed out of that one to hold a renegade convention a few weeks later. At that event, one of his Rough Riders was observed drunkenly walking the floor with guns drawn.