Alternative sports histories are nearly as popular as the sports themselves. Fans love to consider (and argue over) the effects of the ultimately unknowable “what-ifs” of sports. For example:

The most intriguing what-ifs concern the alternative histories of a sport. For example:

- What if Boston hadn’t sold Babe Ruth to New York, or if Ruth had continued playing as a pitcher?

- What if Jackie Robinson had never been allowed to play in the whites-only major leagues? Or what if the racial barrier had been breached before World War II, and renowned white batters had faced black pitchers like the phenomenal Satchel Paige?

- What if basketball hadn’t lost Bill Walton or Penny Hardaway to injuries?

- What if Muhammad Ali hadn’t had his boxing license suspended for civil disobedience during his late 20s?

- What if Bill Buckner hadn’t missed that ground ball in the 1986 World Series?

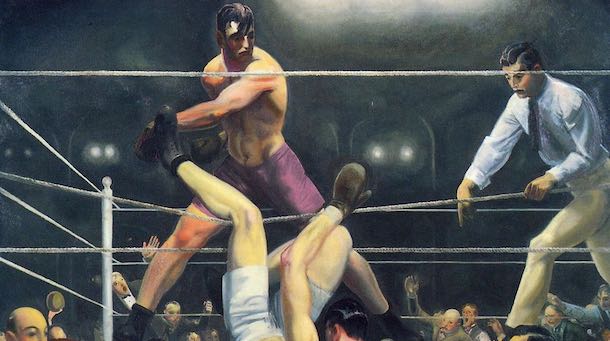

One of the great never-to-be-settled what-ifs involves the 1927 Dempsey-Tunney heavyweight championship fight and the infamous “long count.” On September 22 of that year, more than 100,000 boxing fans crowded into Soldier Field to see Jack Dempsey try to win back his heavyweight title from Gene Tunney.

In round seven, eight rapid hits from Dempsey sent Tunney to the mat. Usually, Dempsey would stand over his fallen opponent, ready to beat him back down. But a new rule required boxers to go to a neutral corner before the referee would start counting their opponent out.

Forgetting this, Dempsey remained beside Tunney. The referee finally shoved Dempsey to a corner and only then began his count — nearly five seconds after Tunney fell. At count “nine,” Tunney rose to his feet. Those extra seconds became known as the “long count.” Tunney later claimed he could have regained his feet early in the count, but took the extra time to recover. And Dempsey said he had no reason to doubt him.

When fans read about the match in 1927, they believed Dempsey was robbed. Only when films of the contest were released in newsreels did Americans see that the count was not as long as they’d imagined. But some fans held onto the idea that, with a proper count, Dempsey would have won with a technical knock out.

Boxing aficionados continue to speculate about what might have been. In the Post four years later, one man with a unique perspective on the fight weighed in: Jack Dempsey himself. In “In This Corner,” although he recounts the fight and the events surrounding it, he hardly lays the controversy to rest. He does, however, take a broader, more pragmatic view of his life as a boxer and of that fight in particular.

In This Corner

by Jack Dempsey

Excerpted from an article originally published on August 29, 1931

Following my knockout victory over Jack Sharkey, Tex Rickard immediately propositioned me for another match with Gene Tunney.

“The old iron is hot again, Jack,” Tex said to me. “Now is the time to strike. This win over Jack Sharkey puts you right out front with Tunney himself. You laughed at me a few years ago when I told you that we would draw $1,000,000 with the Carpentier fight. Laugh at me now, if you dare, when I tell you we’ll draw at least $2,500,000 with you and Gene in the ring again.”

Who can know but that man who has lived through the experience what it means to wonder whether you are good or bad? I had every reason to feel I had been a great fighter. I hadn’t as yet had incontrovertible evidence that my day was gone. The old fighting heart and the old fighting instinct throbbed within me for expression. I hated the thought of anybody else in possession of my heavyweight championship. I reasoned the thing out very carefully in my own way; thought it out when I was alone at night with none to bother me.

There was one thing which seemed certain to me. That was that I would knock out any man I hit right. What if my legs had slowed up a trifle? What if the old zip and speed were gone from my bobbing and weaving? These things must essentially be offset by experience and by knowledge. I felt strong as an ox, and because most of my contests had been short, I had never really taken any serious beatings. Why, then, should I not gamble that at least once in 10 long rounds I could tap Gene Tunney on the chin, or under the heart, with a punch that would win me back the heavyweight championship of the world? There was no good reason to suppose such a thing unreasonable. I felt that I could hit Gene; felt that I could plan out a campaign of battle that sooner or later would bring him to me for that one lovely punch.

With this in mind, I considered the possibility of a $3,000,000 box office. Aside from the money that would establish Tunney and myself as the greatest financial figures boxing had ever produced, I was a comparatively rich young man when these problems presented themselves. I could have retired then as easily as I retired later, and lived on my income.

So it was not entirely money by which I was actuated. There was — and I do not say it sentimentally — an appreciation and a love for the sport of boxing which superseded in my calculations every financial angle. I think, perhaps, I was a big kid who had lost a toy and wanted to fight to get it back again. In any event, I told Tex Rickard to match us and I promised myself that I would give Gene Tunney a whole lot better fight than I had given him that rainy night in Philadelphia.

My contest with Jack Sharkey netted me almost $500,000 and, to put it in the jargon, I was sitting pretty, financially. There was nothing between me and retirement other than a determination on my part to satisfy that hankering wonderment as to my own condition. I knew perfectly well that I wasn’t 30 percent of the old Jack Dempsey the night I lost my heavyweight championship. On the other hand, I knew perfectly well that Gene Tunney was a fine fighter and a whole lot better than the public has ever given him credit for being. There lay the problem.

I knew that my win over Sharkey indicated that I was in fair physical condition. I felt that a good training siege would put me back in excellent condition. Furthermore, I was perfectly certain that when I was in condition, the man did not live who could box me 10 rounds without at some time or other being hit on a vital spot. I knew perfectly well, as I have said, that anyone I hit on a vital spot was very apt to be counted out. That was my bet on the Tunney fight at Chicago. I believed that the worst I had was a 50-50 chance to regain the championship, and that is exactly the right percentage for a great fight.

I went to Chicago to train. Leo Flynn once again took charge of my training and acted in the capacity of chief adviser. I think that most of the fellows who realized my condition before the first Tunney contest favored me to win over Tunney in the second. There were all sorts of rumors floating about my camp to the effect that the gamblers had everything set against me once again. This time I did not easily fall for those rumors.

No Fixers Wanted

I had been knocking around the $1,000,000 gates long enough to know that a good many shady things were attempted. But I also had seen enough of Gene Tunney to know that it was not in his mind or his heart to fake a championship prizefight. This absolute confidence in Gene gave me the greatest weapon I had to use against the fixers who later approached me.

It is not easy to sit here and write these details. I feel that I must do it, however, in justice to myself and in justice to Gene Tunney. I have often hoped, to be truthful about it, that Gene would write his life experiences. I certainly would like to read them and get the other side of our two contests. In my own relation of events, I have stated the absolute and simple truth just as closely as I know how. I know that Gene would do the same thing. Out of a contrast of the two stories a pretty situation ought to develop.

I positively was approached by people in Chicago. I was, in fact, told that for $100,000 I could win the heavyweight championship. I laughed in their faces for a good many reasons, the principal ones of which I am going to relate. They are so obvious and so indisputable that none can deny them.

First, I refused because I had planned a careful campaign against Gene Tunney and believed that I could beat him on the level. Second, I never would trust anybody who would take or give a bribe. Third, I have never faked a fight in my life and I never will. Fourth, even if I did lose my head and pay such a craven bribe, I knew nobody could fix Gene Tunney, and Gene Tunney was the man I had to fight. Next, despite the advice of some people who harassed Leo Flynn and myself, I felt that my coming contest with Gene was the last I ever would fight, win, lose or draw.

If I won, I planned to retire undefeated. If I lost, nothing more need be said. So I laughed in their faces when they made me this proposition.

The fight itself has hardly wilted sufficiently in the public memory to warrant a detailed description here. I went into the ring planning to work on Gene much after the fashion I had worked on Jack Sharkey in my last contest. In Tunney, however, I was fighting a better fighter than Sharkey. I do not wish to be unkind in that statement; I merely state the fact.

Down for the Long Count

No matter what happened, Gene remained as calm as a mill pond. At times, his machine-like perfection was maddening to me. That darting, straight left jab of his, coupled with an inside, straight right cross that had great jarring possibilities, sufficed to fill anybody’s evening with bouquets that were loaded with reverse English. Gene could fade away from an attack and at the same time hook a jarring left to the liver as well as any fighter who ever lived. So I did not fight him exactly as I had Sharkey. I took more precautions. I felt from my first experience with Tunney that he would draw the lead from me and counter. I planned my campaign entirely on that supposition. It worked out perfectly.

Just as I had planned, I finally got my shot at him. The rest is history. The fact that it is disputed history is of no vital importance at this moment. I have stated previously in my story what Tex Rickard said to me on the afternoon I boxed Georges Carpentier. He told me that I was the sort of a kid to whom things happened.

There are people like that, and I am confident that I am one of them. Even in my present activities, events can run along at a fight club in the even tenor of their way, show after show after show. But let me appear in the capacity of referee and the unusual happens. This has recently been true twice in Madison Square Garden at New York City. It was true the other night in Los Angeles. It seems to me to be true wherever I go. It certainly was true that night in the Chicago Stadium when I caught Gene Tunney in a corner of the ring and knocked him down for the historic “long count.”

If anyone thinks that I am here to express any opinion as to the merit of that “long count,” they have another think coming. All I have to say about that hectic contest is that I fought the best that I knew how to fight. I put into that battle everything that I could summon in the lexicon of physical equipment and experience. When I cornered Gene and knocked him down, I felt the exultance that came to me that July Fourth in Toledo when I won the championship from Jess Willard. Gene was down, and, boys, he had been hit! A look at the motion pictures of the battle will indicate just how many punches Gene absorbed as he toppled over there against the ropes.

I want to say something else in terminating my story. Gene Tunney, on the floor of that Chicago ring, showed the world more of the stuff of which a champion is made than he did in the entire fight at Philadelphia. I don’t think Gene even knows how to spell quit, and I don’t think he’ll ever learn how to spell it. He has the equipment and the heart of a champion. Had he not, he never would have got up off that ring floor in Chicago inside a hundred count.

All the way through that contest, I figured it a hard-fought and close one. After Gene had got up, following that knock-down, he gave a great exhibition of thinking under fire. I could not catch him for the rest of the round to land a finishing punch. But I kept right on trying in the next round, and as a result of my over-anxiety, Gene dropped me to my knees for a count of one.

It was a red-hot fight, and I don’t think anybody could criticize the performance of either of the contestants. Gene won the decision and remained heavyweight champion of the world. To say that I was not disappointed would be to tell a lie. I was disappointed. But once again I had collected a modest fortune for my efforts, and there was a good deal in my life to console me for the missing heavyweight championship.

After the Fight

There was a home and a wife in Hollywood. There was plenty of money in the bank to take care of me and the family I had caused so much worry in my younger days. There was the Firpo fight, the Carpentier fight, the Fulton fight, and several others which had marked the very peak of thrills for the boxing public. Of none of these need I ever be ashamed. After all, that man who wins a championship should be content. He should not expect to hold it over the hurdles of the onrushing years.

In my dressing room after the second Tunney contest, I was momentarily dejected. As is always the case with dressing rooms, a great many people I did not know managed to crowd in. I presume this is curiosity on their part, and it may be morbid curiosity. A fighter, in defeat or victory, is much like a monkey in a zoo to those who can get close to him. They want to look at your eyes and your ears to see how badly you may have been injured. They want to pick up a word here or a gesture there which, later on, they can relay, magnified, to their own little public.

I have always regarded these curious fans in a tolerant, even friendly way. They are, I presume, out of the great masses which support professional boxing. But I never had come to regard them seriously, nor did I ever expect to receive from one of them a perfect gem of philosophy. But I did.

It came from an emaciated chap weighing not more than 130 pounds, in high boots and an overcoat. I never will forget him. He had a hooked nose and sharp little eyes that winked incessantly under thin, scraggly eyebrows. He was smoking a cigarette when first I saw him, puffing a cigarette and looking intently at me.

I sat down on the edge of a rubbing table and my handlers began removing the bandages from my fists. The little chap wore a brown suit and shifted uneasily from foot to foot. He smoked jerkily at his cigarette, inhaling nervously and blowing the smoke upward so that it curled under the brim of a shabby, brown felt hat.

What’s a Championship?

I noticed, for no particular reason, that his fingernails were in deepest mourning about their tips. I grinned at him and winked. He took the gesture as a personal salutation which seemed, from his expression, to illuminate his life.

“Okay, Jack,” he called to me.

I grinned and winked again. Newspapermen crowded about, but they did not get between us. The little stranger saw to that. One of the newspapermen said:

“Jack, do you realize that Tunney was down for 17 seconds?”

“No,” I said. “I don’t know how long he was down.”

“Why didn’t you go to a neutral corner?” the newspaperman demanded.

“I meant to,” I admitted, “but there didn’t seem to be any hurry about it. The count had started and I thought it would continue.”

One of my seconds growled: “He’s still champion of the world, ain’t he? How many times do you have to count a guy out to win? Seventeen seconds!” Some other newspaperman spoke up, “It was only 14 seconds,” he said.

“Well,” my handler growled, “up till tonight, 10 seconds has always made a champion! I’m tellin’ you guys right now that, with the great majority of American boxin’ fans an’ with everybody who knows anythin’ about the prize ring, Gene Tunney got a decision tonight, but Jack Dempsey is the heavyweight champion of the world!”

“No, he ain’t either,” the newspaperman returned laconically. “They don’t reverse those decisions. If you had a kick to make, you should have pulled Jack out of the ring when it all happened. It’s too late now.”

“Not with the real fans who know the racket, it ain’t,” my overenthusiastic second insisted. “With them, Jack Dempsey is the heavyweight champion of the world. It’ll never be any other way.”

The newspapermen looked at me.

“What do you say about it, Jack?” they demanded.

I shrugged. “I’ve got nothing to say, boys. You saw what went on in there and you’re damned sight better judges than I am. I was too busy trying to fight. But don’t get this handler wrong. It’s his loyalty as much as his judgment that speaks.”

Suddenly a piping, unimportant voice rose from near at hand. I glanced up, and it was the fellow in the little brown suit with the shabby felt hat and the fuming cigarette.

“What the hell!” he exclaimed stridently. “What if he is champ, or what if he ain’t? He’s young, ain’t he? He’s got dough, ain’t he? He’s famous, ain’t he? I ask you, what the hell’s the champeenship of the world to a guy like that?”

So, from the great mass whose gift to me was fame and fortune, came finally a philosophical gem in the shape of unintentional advice. This little chap was right. I had my share of the fame and the fortune. I had lived down the things that once were held against me. I had been champion of the world, and I had been a fairly good one.

Suddenly the sun-washed shores of California looked awfully good to Jack Dempsey. I urged my handlers to hurry with their tasks that I might the sooner get to a telephone and talk with my wife. I thought again of what good old Bill Brennan had said when defeat overtook him in the person of myself. “That’s the fight racket.” Two cannot win a fight, and I’d had more than my just share of victories.

I looked again at the anemic little man in the brown suit. His sharp little eyes peered right straight back at me. While the others worked on me, I grinned again and winked at him. Whether he knew it or not, there was a world of appreciation in that final gesture.

For Dempsey’s full account, including his views of his first loss to Tunney in 1926, read “In This Corner” in full here.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now