Put Away Your Smartphone

Last summer, my husband and I went to Italy for a second honeymoon with stops in Verona, Florence, and Venice, but thanks to modern technology, our dream vacation turned into something of a nightmare.

The al fresco operas held in a 2,000-year-old arena in Verona are impressive with massive sets, orchestras, and choruses. As the sky darkened on the evening we went, the overture began, the singers poured onto the stage. That is also when the people directly in front of us lifted up their iGadgets and began recording the performance. Occasionally they would lower their arms for a short rest between arias, but most of the time I was forced to watch the opera through the tiny screens of their smartphones. I felt like I was watching television with the picture within a picture feature on, except the smaller image was from the same show and corrupted the fuller picture with its intrusion.

From Verona we trained to Florence where there is more art than you could shake a selfie-stick at, so we rushed over to the Galleria dell’Academia to get started with Michelangelo’s masterpiece, David.

David, at 17 feet tall, towers above the crowds in magnificent milky marble splendor. However, standing in front of the sculpture I could only see slivers of him through the forest of arms holding up smartphone and tablet cameras that our fellow tourists brandished above their heads.

Being away from the noise and frenzy of modern civilization was all I could think about as our train carried us away from frenetic Florence. I was instantly captivated by Venice’s picture-postcard views of gondolas, canals, and colorful low-slung homes. On our first night there, the disappointments of Verona and Florence drained away as we sipped Prosecco in a charming café. I could almost hear the music of Vivaldi, Venice’s native son, ringing through the damp air. But what I thought was the opening to The Four Seasons violin concerti turned out to be a text notification on the smartphone of someone at the table next to me. For the following four days, until the end of our vacation, I heard cellphone alerts in some of Venice’s finest churches, galleries, and restaurants.

I am grateful for the technology that allows me to access email, driving directions, and answers to questions I have long since forgotten like “In what year was the film Sunset Boulevard made?” at the touch of a button or two. But while we can now see or hear any masterpiece of art, performance, architecture, or postcard-worthy nature vista on any smart gadget wherever in the world we are, I would prefer to view these things the old-fashioned way — standing right in front of them, absorbed by the atmosphere that transports me to a different time and place.

The Illustrator’s Apprentice

Roger Morgan/Boy Scouts of America

As a boy, I loved to sit in my father’s studio listening to the scratch, scratch, scratch of his paintbrush on the stretched canvas on his easel and see the strokes of color gradually grow into pictures. He whistled while he worked — mostly Sinatra tunes, Beethoven, some Willie Nelson. And he sang Roger Miller: “Two hours of pushin’ broom buys an 8-by-12 four-bit room. I’m a man of means by no means, King of the Road.”

Dad is one of the happiest people I’ve ever met. I mean, how could you whistle for 10 hours a day and not be happy? I’m sure it’s because, even at age 87, he’s doing exactly what he has loved to do since, as a child, he began doodling pictures of the Lone Ranger, sitting in a dress factory cloth bin next to his Hungarian mother, Emma, while she sewed.

Joseph Csatari tells stories in pencil and oil paint. He is a workman illustrator and meticulous draftsman in the tradition of The Saturday Evening Post artists Norman Rockwell, Stevan Dohanos, and Al Parker, who were his friends. In a career spanning 68 years, he has made thousands of paintings, portraits, and illustrations for magazines, books, advertisements, and collectibles. His work has appeared in Boys’ Life, Reader’s Digest, McCall’s, Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, and Time, among others. His cover illustrations have sold books for Simon & Schuster, Dell, Bantam, and Pocket Books. Csatari’s ability to depict the humor and wholesome ideal of American life made him a go-to illustrator in the 1980s and ’90s for advertising and corporate branding campaigns for the Coca-Cola Company, Coleman, Nabisco, Hardee’s, Taft Broadcasting, Stern’s Miracle-Gro, Chef Boyardee, Mutual of Omaha, and, of course, the Boy Scouts of America — where his professional career began in 1953 as a “layout man” in the advertising department.

After more than eight years as art director to Norman Rockwell for his annual Brown & Bigelow Scout calendar paintings, Csatari became the second “official artist of the Boy Scouts of America” after Rockwell’s retirement in 1977. In a letter to the Boy Scouts in 1976, Rockwell wrote: “In a sense there is a strange parallel between this young man and myself. Joe Csatari, until only recently, has been Art Director of Boys’ Life. In my own youth I worked for Boy Scouts in the same capacity.”

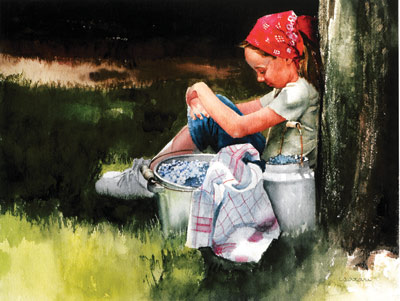

Csatari sits in the morning light in the studio of his home in South River, New Jersey, paging through volume one of Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue. On his easel is a nearly finished watercolor painting.

© Joseph Csatari

“I like watercolor; it’s fast and loose,” Csatari says. “As you can see, I’ve been painting a lot of ducks and horses lately. But what I really love is painting people.”

He stops flipping pages at Thanksgiving Day Blues, Rockwell’s November 28, 1942, cover for The Saturday Evening Post, showing an exhausted army chef having a smoke after preparing a 34-item meal for a brigade at Ft. Ethan Allen, Vermont.

“I remember copying this one when I was a boy,” he says. “Look at the detail in those hands. Amazing! Norman was a master of the human form.”

Csatari was 12 years old when he started copying Rockwell’s Post covers in a sketchbook. Each week, Csatari’s older brother Johnny, an aspiring artist himself, would bring home the magazine, and the two of them would practice copying the covers of Dohanos, John Falter, Rockwell, and other illustrators in pencil and oil paint.

“As long as I can remember, I wanted to paint like Rockwell,” Csatari says.

In elementary school, Csatari’s teachers recognized his proficiency early on and encouraged him. In fifth grade, he was selected to lead a crew of students to paint a 25-foot mural on the school’s walls titled I Will Prepare Myself Today, for Someday My Chance Will Come.

In high school, Csatari enrolled in the Famous Artists School, a correspondence course started by Albert Dorne and other members of the Society of Illustrators, because Rockwell was one the featured illustrators. Later, when Csatari attended the Newark Academy of Art, he took an after-hours job sweeping floors in the school’s museum so he could study the original paintings in the collection. One night, with his nose inches from a Rockwell painting, he noticed a loose paintbrush bristle stuck in a heavy stroke of paint. He plucked it, wrapped it in chewing gum foil, and put it in his wallet. He still had that purloined paintbrush bristle in his wallet in 1968, when he visited Rockwell’s carriage house studio in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, for the first time.

“Because of Rockwell’s tremendous workload, Csatari was chosen to assist him in coming up with ideas for future Scout paintings,” says Dr. Donald Stoltz, a Rockwell historian and author of several books on Rockwell. Stoltz and his brother Marshall owned the Philadelphia Norman Rockwell Museum, across the street from Independence Hall in the Curtis Building, where The Saturday Evening Post was published for many years.

Courtesy Joseph Csatari

Csatari’s task was to make preliminary rough sketches for Rockwell. When they were approved, his job intensified; he’d select models, gather props, and transport crew and equipment to the Stockbridge studio where he and Rockwell would direct photo shoots.

“They worked so closely together that they began thinking along the same lines,” Stoltz says. “Eventually, when Norman’s age started catching up with him, Norman asked the young artist to paint in some details. He really appreciated having Csatari’s help, and, of course, sitting in his mentor’s chair, using his brushes, was a huge thrill for Joe.”

On one of Csatari’s early visits to Stockbridge, he walked to The Old Corner House museum while Rockwell took his midday nap. Long before the current Norman Rockwell Museum was built, The Old Corner House displayed many of his paintings, including The Four Freedoms, large canvases illustrating the four fundamental freedoms Franklin Roosevelt outlined in his 1941 State of the Union address. “I remember feeling as if I had entered church,” Csatari says. “But then the reverence was broken when I noticed men painting the ceiling, and I worried they would spatter those glorious paintings below. I hurried to tell Norman. He just took a thoughtful puff of his pipe, smiled, and said, ‘Gee, Joe, maybe they’ll improve ’em.’ That’s how Norman was — very modest and always focused on what was the next job.”

“In a sense there is a strange parallel between this young man and myself.”

—Norman Rockwell

Csatari recognized Rockwell’s enormous talent and the value of his artwork perhaps even more than Rockwell himself, and certainly more than the critics did, during the late ’60s and ’70s. He recalls being asked in the late 1960s to transport four Rockwell paintings from a museum in central New Jersey to New York City, where Rockwell was to appear on NBC’s Today show. He placed them in his station wagon under blankets. “My teeth chattered the entire way, there and back,” Csatari says.

Upon taking over the Scout calendar commission from Rockwell in 1977, Csatari resigned as a BSA employee and began freelancing full time. He converted his garage into a studio, installing floor-to-ceiling windows to capture the northern light. Through contacts at the Society of Illustrators in New York and an agent, Csatari’s commissions grew, but slowly. With a young family to support, he supplemented his illustration income with portrait work.

Csatari’s talent for capturing a person’s image and personality on canvas became apparent in art school. While attending the Newark Academy of Art, Csatari worked from a photograph to paint a portrait of then-president Dwight D. Eisenhower. The school’s dean was so impressed with the work that he arranged for Csatari to present the portrait to the president at the White House.

“Eisenhower emerged from a meeting looking very tired when I met him, but he flashed that famous grin when he saw his portrait,” Csatari recalls. “He liked to paint, too. And he asked me if I used raw umber for the underpainting. He was right.”

© Joseph Csatari

Csatari recently learned the whereabouts of that portrait. When he left office, Ike gifted the portrait to his valet and family friend of 27 years, Johnny Moaney. Today, it remains with the Moaney family.

Csatari has painted the likenesses of Thomas Watson, Norman R. Augustine, Sanford N. McDonnell, Stephen Bechtel Jr., first lady Betty Ford, Archbishop Theodore E. McCarrick, musicians from Bing Crosby to Frank Zappa, and actors Leonard Nimoy and James Whitmore.

Portrait work filled in the gaps between illustration assignments, generally paid better than illustration did, and allowed him more liberal deadlines. “There was always something new to paint, even now, but I’m 87 and a lot slower with the brush,” Csatari laughs. Often, he had to create an illustration in just a few days — a deadline of a week or two was a luxury. For example, an art director for Time magazine once asked him to create a scene showing Jimmy Carter’s press aid and chief of staff, Jody Powell and Hamilton Jordan, dressed as Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn and whitewashing the White House fence. Csatari quickly recruited his niece’s husband to play Jordan while he himself posed as Powell. Both wore overalls and straw hats. My mother, Susan, took the photos of them in dad’s studio. The painting was finished in two days but ultimately wasn’t used due to a changing news cycle.

“As an illustrator, you had to move fast to keep up with the work when it came,” Csatari says. “And sometimes you were disappointed and had to settle for a kill fee, if you got anything at all.”

As art directors recognized his work, Csatari’s career became busier. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, longtime Post cover illustrator and fellow Hungarian Stevan Dohanos arranged for Csatari to create two U.S. postage stamps, Seeing for Me, honoring Seeing Eye dogs, and The Gift of Self, commemorating the American Red Cross. Through the 1980s and ’90s, Csatari illustrated hundreds of stories and articles for popular magazines. During this period, Csatari became a prolific illustrator of book covers, creating illustrations in oil for novels and nonfiction books by Bill Bryson, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, and Anne Baxter and for books for young readers by Paula Danziger and even Thomas Rockwell, one of Norman Rockwell’s two sons.

“I would read each manuscript and search for a high point of emotion or humor to illustrate,” Csatari says.

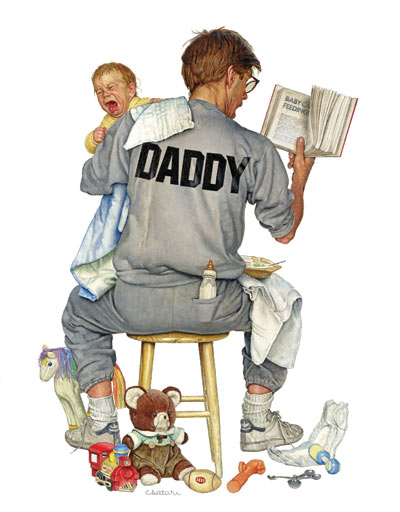

© Joseph Csatari

A book called Daddy shows a new father from behind holding his screaming child over his shoulder. Toys, rattles, and diapers are strewn on the floor, and in the father’s other hand is a book opened to the chapter “Baby Care and Feeding.”

“The problem was our baby model was so sweet and happy,” recalls Csatari, who felt he needed a wailing baby for the portrait. “She wouldn’t cry during the photo shoot. No matter what I did, she just laughed and smiled. Then the mom said, ‘Oh, wait a second,’ and she stuck her fingers in some water and flicked it in her face. Oh, geez, did that baby give me the cry I was looking for.”

Each piece of Csatari’s artwork reflects not just an image, but an impression, a story that needs to be told,” says Gail Mayfield, collections manager for the National Scouting Museum in Irving, Texas, which houses 50 of Csatari’s Scout paintings alongside those of Rockwell. Mayfield believes that while Csatari’s work is reminiscent of Rockwell’s, Csatari “developed his own personal style that reflects both the fun and service sides of Scouting with vivid color and emotion that draws viewers into his world.”

While probably best known for his Scouting illustrations, Csatari’s portraits, fine art watercolors, and cover illustrations have appeared in exhibits at the James A. Michener Art Museum, the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, the National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island, and the College Football Hall of Fame. A few galleries specializing in illustration art sell his paintings, but he has never actively sought out galleries to promote his work.

Courtesy Boy Scouts of America

Currently, my father is working on his 55th or 60th — he has lost count — painting for the Boy Scouts of America. It’s a piece showing Scouts trading patches at jamboree. I’m there, modeling as a Scoutmaster. My daughter Lydia is wearing the uniform of a Venturer, the BSA’s co-ed program for teens. We’re with a couple of older Scouts watching two young guys haggling over a trade. The Scouts are in colorful printed T-shirts and high-tech khaki shorts, very different from the immaculate starched uniforms emblazoned with insignia that Rockwell painted. Dad coaxed enthusiastic faces and “big eyes” from us at the shoot. (He, like Rockwell, works from photographs.) Maybe we look a little goofy, but it’s clear we’re having fun, and that’s his goal — to make Scouting look like a lot of fun.

For Stoltz, who authored Norman Rockwell and The Saturday Evening Post, that’s what makes Csatari’s artwork reminiscent of Rockwell’s. “His characters are filled with wholesome enthusiasm,” Stoltz says. “When my wife, Phyllis, and I lecture on Mr. Rockwell’s work around the country, the most asked question from our audience is, ‘Who paints most like Norman Rockwell today?’ And the answer I give every time is ‘Joseph Csatari.’”

Though flattered, my father has always struggled with such comparisons. “Norman was in another realm with the likes of Leyendecker, Dean Cornwell, and N.C. Wyeth,” he says. “I was certainly influenced by Norman and, like him, I love to paint people.”

“Why?” I ask.

“Well, because we are all made in God’s image, and there’s something spiritual about painting people that I find so very rewarding.”

—

To learn what it was like to model for Norman Rockwell, read “A Lofty Assignment” by Jeff Csatari.

The Beggar on Dublin Bridge

“A fool,” I said. “That’s what I am.”

“Why?” asked my wife. “What for?”

I brooded by our third-floor hotel window. On the Dublin street below a man passed, his face to the lamplight. “Him,” I muttered. “Two days ago —”

Two days ago as I was walking along, someone had “hissed” me from the hotel alley. “Sir, it’s important! Sir!”

I turned into the shadow. This little man in the direst tones said, “I’ve a job in Belfast if I just had a pound for the train fare!”

I hesitated.

“A most important job!” he went on swiftly. “Pays well! I’ll mail you back the loan! Just give me your name and hotel—”

He knew me for a tourist. But it was too late; his promise to pay had moved me. The pound note crackled in my hand, being worked free from several others.

The man’s eye skimmed like a shadowing hawk. “If I had two pounds, I could eat on the way—”

I uncrumpled two bills.

“And three pounds would bring the wife—”

I unleafed a third.

“Ah, hell!” cried the man. “Five, just five poor pounds, would find us a hotel in that brutal city and let me get to the job, for sure!”

What a dancing fighter he was, light on his toes, weaving, tapping with his hands, flicking with his eyes, smiling with his mouth, jabbing with his tongue.

“Lord thank you, bless you, sir!”

He ran, my five pounds with him. I was half in the hotel before I realized that, for all his vows, he had not recorded my name.

Purchase the digital edition for your iPad, Nook, or Android tablet:

To purchase a subscription to the print edition of The Saturday Evening Post:

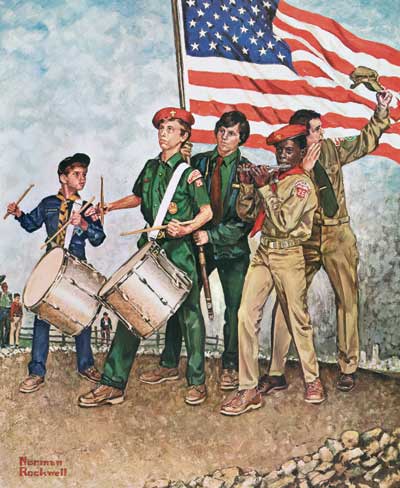

A Lofty Assignment: Modeling for Norman Rockwell

© Brown & Bigelow, Inc., St. Paul, Minnesota/Courtesy Boy Scouts of America

I was 10 years old when Dad made me jump into the station wagon with a bunch of Boy Scouts for a five-hour trip from New Jersey to Norman Rockwell’s studio in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

I didn’t want to go.

When we arrived, there was half an inch of snow on the ground. So I looked for pigeon-toed footprints in the snow leading to the red carriage house studio — having heard the story of the artist’s famously awkward feet — and found them.

Inside, I marveled at the African masks and spears on the walls and the replica of Ben Franklin’s printing press. On his easel sat a large horizontal painting of Abraham Lincoln having his photograph taken. On a low shelf, I saw a skull wearing a German spiked helmet. Springs attached to the jaw made it snap shut when you spread it.

Dad told me to stop touching stuff.

Rockwell and photographer Louie Lamone arranged the Scouts and Scoutmaster, my uncle Byron, in a line as if marching in a parade. My cousin Byron, in Scout uniform, carried a drum. An older boy held an American flag on a pole.

“It needs to fly,” Rockwell said as he tied a string to the top corner of the flag and turned to me. “Jeff, take this and climb up to the loft,” he said, sounding as if he had marbles in his mouth. I obeyed. It was hot up there. The flag rose in the simulated wind and the shot was snapped.

Rockwell gave me a check for $25 for the job. I cashed it when I got home and bought a Joe Namath football. The football’s long gone, but Dad was wise to make a copy of the check, which I now have framed, proof of the tiny role I played in Norman Rockwell’s last Boy Scout painting.

—

To read more about the author’s father, artist Joseph Csatari, read “The Illustrator’s Apprentice.”

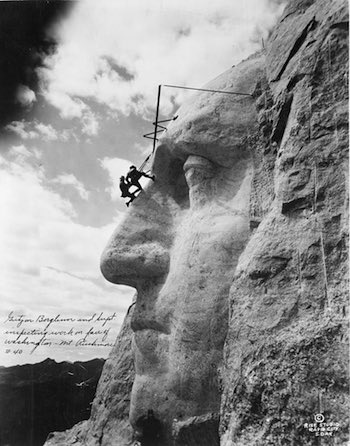

The Larger-Than-Life Artist Behind Mount Rushmore

It began as an ambitious plan to boost tourism in South Dakota in 1926. When it was completed 15 years later, it became an American landmark and a symbol of the nation’s determination and skill. In between 400 workers did the grueling work of blasting and drilling 410,000 tons of granite from the side of the mountain under the supervision of a gifted sculptor named Gutzon Borglum.

But Borglum’s gifts weren’t limited to pulling heroic images out of mountains. He also showed considerable talent in promotion, both for the project and for himself. As the governor of South Dakota during Mount Rushmore’s construction, William J. Bulow was well acquainted with this side of the artist. His article “My Days with Gutzon Borglum,” which appeared in the December 1, 1947 issue of the Post, outlines Borglum’s fickle and often maddening ongoing requests and demands, as well as his genius.

Securing the necessary funds for the project proved as difficult as carving the gigantic granite heads. The federal government approved the project in 1926, but most of the work was performed during the Great Depression, when money was particularly hard to come by. Ultimately, the memorial was a scaled-back version of Borglum’s original design. He had intended to sculpt the presidents down to their waists, but time and money were too limited.

Time was even more limited for Borglum himself. He died in March of 1941, leaving his son, Lincoln Borglum, to complete the project. Later that year, funding ran out: The government was focused on rebuilding national defense (the Pearl Harbor attack was just weeks away.) So Mount Rushmore was declared completed on October 31, 1941.

Though it wasn’t as grand as had been originally intended, Borglum left an enduring tribute to four presidents who represented the founding of the nation (Washington), its expansion (Louisiana Purchaser Jefferson), its development as a global power (Roosevelt), and the preservation of the union in the Civil War (Lincoln). Today, this national memorial is maintained by the U.S. National Park Service.

But Mount Rushmore is also a tribute to the artist, who emerges as a larger-than-life figure in Bulow’s article.

My Days with Gutzon Borglum

By William J. Bulow

Originally published on January 11, 1947

Ever hear about the time when the famous sculptor walked up Mount Rushmore in the rain and got his white pants dirty? The governor of South Dakota heard plenty about it — and other unfortunate incidents.

In the spring of the first year I was governor of South Dakota, the annual convention of the Young Citizens League was held at Pierre. This was a new state-wide organization of school children below the high-school grades, and I was much interested in its welfare and success. At one of the convention sessions, Doane Robinson, the state historian, submitted a proposition that the Young Citizens League take charge of raising funds for the Rushmore Memorial. Until that moment, I had never heard of the Rushmore Memorial.

I listened to the proposal and then asked for permission to appear before the league in opposition, contending that the children in the grade schools ought not to be burdened with a proposition of this kind. The league turned the proposal down.

Not so long after that, however, Doane Robinson, in company with Gutzon Borglum, came to me and with a good deal of enthusiasm discussed what they had in mind. It sounded all right, but at that time I was not much excited. Their plan was to raise the necessary funds by public donation and subscription. Funds for a starter had already been subscribed.

Borglum, who was a born promoter, then worked up a great advertising stunt by having President Coolidge, while he was visiting the state, dedicate the mountain. The services drew a tremendous crowd of people. In addition to the President’s address, the event gave Borglum a chance to make a speech and tell what he intended to do. He actually had the fortitude to “authorize” President Coolidge to prepare a short history of the United States, of a few hundred words, which he, Borglum, would then carve on the mountain peak opposite the gigantic statues of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt, which he planned to hew out of the granite. President Coolidge accepted the job, but he didn’t know what he was getting into. When the manuscript was completed and submitted several years later, about the time Mr. Coolidge’s term expired, the sculptor decided it was wholly unsatisfactory and turned it down flat.

Next, Borglum got the Hearst newspapers interested in a Mt. Rushmore promotion scheme and staged a widely publicized contest, offering a first prize of $10,000 for the best short history of the United States. More than 10,000 persons, from all sections of the country, submitted manuscripts. A general committee was named to select the five best, and the five thus chosen were submitted to a special committee of five United States senators for the final choice. By that time I was a member of the United States Senate and was one of the committee of five.

In my judgment, all five manuscripts were excellent; any one of them was worth carving on the mountainside. The committee made its choice, and Borglum promptly turned it down. Moreover, he took a look at the four others and threw them away. He said that someone would have to produce a better history than had yet been written or he would write one himself. Borglum had, however, accomplished one of the things next to his heart — the advertisement of Gutzon Borglum and Mt. Rushmore. A million dollars could not have purchased the advertising that the Hearst papers gave Gutzon, Mt. Rushmore, and the state of South Dakota in publicizing the contest.

The original Mt. Rushmore committee was a group of local citizens that Doane Robinson had gathered together and interested in the proposal. This committee was succeeded by a larger and very prominent group of wealthy and philanthropic citizens scattered all over the United States. Considerable sums of money were thus raised in the earlier stages of the work. In order to give more permanency to the project, Congress created the national Mt. Rushmore Commission, the members of that commission to be appointed by the President. Since the death of the sculptor several years ago, the Rushmore Memorial has been placed under the supervision of our national-park system. From the time Congress created the Mt. Rushmore Commission, the work has been financed by federal appropriations from year to year.

One of my headaches during my 12 years in the Senate was the obtaining of necessary appropriations to keep the work going. Gutzon Borglum was not an easy man to work with, but he was, I am convinced, a really great sculptor. I doubt that any other artist living had the vision and the ability to carve those magnificent heads in the living granite of a mountainside. But as a financier and diplomat, Gutzon stood down on the bottom round of the ladder. To obtain the necessary appropriations for the first few years under the national commission was comparatively easy, but the job became harder each year, until toward the last it was nearly impossible.

Borglum always insisted that he himself should appear before the appropriations committee in behalf of his requested budget. His memory was not very good and he had difficulty in remembering his statements from one meeting to another. Some of the committee members, on the other hand, were hard-boiled and had good memories. Gutzon would nearly always end his plea to the committee with the promise that this would be the last appropriation he would ever ask; this would wind up the job. The next year he would be back asking for a substantial increase because he had thought of a lot of new things that he was going to add to the memorial.

At one point he decided that there ought to be a Hall of Fame. This was to be housed in a large cave excavated in the solid granite of the mountain and would include an archives room where the national records could be stored and sealed — to be opened in 10,000 years. In due course of time he had talked a number of prominent people into letting him make marble busts of them, to be placed in the archives room. And then he thought he ought to carve a stairway from the bottom of the mountain up to the doorway of the Hall of Fame and to the room of archives.

I remember particularly the bitter dispute between Mr. Borglum and Senator Norbeck about the stairway. This was in the New Deal leaf-raking days, the days when the government was hiring people to carry stones from one pile to another and then back again. Senator Norbeck had arranged for a government works project to build this stairway with idle labor in that vicinity. It would be paid for from relief funds and not from Mt. Rushmore funds.

Gutzon blew up when he heard this proposal, and he and the senator got into quite a row. Borglum was no financier, but he knew that he was getting a very liberal percentage commission for every dollar that he spent on the memorial; if the stairway was built with relief labor, he would get no commission on that part of the project. This would be bad, and he would not stand for it. The plan to build the stairway with relief funds was dropped. In fact, the stairway has never been built.

Work was started on the Hall of Fame and the archives room, but never finished. Over the years I urged Borglum in every way that I could to devote all his time to completing the carving of the figures. That was work that he, and only he, could do. If he should die before their completion, the job would never be finished. Any miner, I told him, could blast out the cave in the mountain for the archives room, but there was no one else who could carve the face of Lincoln on the mountain.

Borglum did not expect to die when he did and leave the job uncompleted. The last talk I had with him was just a few weeks before his death. I was begging him to complete the figures, as I had begged him many times before. He said that I need not be disturbed about that. He had just gone through a clinic and had had a complete physical checkup; he was in perfect health, he said, and would live for many years.

I know from personal experience that no one could get along with Mr. Borglum for any length of time without losing his temper — unless one was a saint, and there are few human saints. I never had so many rows with any other person as I had with him — sometimes over important things, but more often over little, insignificant things. We were probably equally to blame. Borglum never carried a grudge.

Early in our acquaintanceship, we often parted in the evening with Borglum vowing he never would speak to me again. But the next morning would be a brand-new day, and Borglum would extend a hearty handshake and a cordial good morning. That cordiality would hold good if we did not visit too long. If we talked too much and discussed too many subjects, it would become necessary for us to part again in anger. Most of my first year as governor, Gutzon constantly made life miserable for me. His chief peeve at that time was that there was no road to Mt. Rushmore. There was just a trail that could be traveled only on foot or by horseback.

When President Coolidge dedicated the mountain he rode horseback up the mountain trail and wore a ten-gallon cowboy hat. There were a few other horseback riders, including Senator Fess, of Ohio. Senator Fess was not a good bronco rider and he was lagging a little behind. The President said, “Senator, ride up here by my side — it won’t hurt you any.” There were not broncos enough to go around, so I walked, as did several thousand other people who climbed the mountain trail that day.

To Borglum, Mt. Rushmore was the most important thing on Earth — the center of the universe. Everything else was of secondary importance. But Mt. Rushmore had no highway leading to it. It must have a highway. The State Highway Commission must build this road at once. The governor was chairman of the highway commission, so Mr. Borglum took all matters up with me. Almost every day he would demand that the road be built, and after each demand he expected that the job be completed before breakfast next morning.

I especially recall one telegram that he sent me. I recall it because it was the longest telegram I ever received and contained the most expressive language. There were more than 300 words in that telegram, and Gutzon didn’t repeat himself. Every word meant something. It was a masterpiece. I wish now that I had kept it to insert here. I remember, among other things, he said that he had just returned from the mountain. That it had rained. That he had worn white shoes and a new pair of white dress pants. That he had driven his car as far as he could and then walked. That he had ruined his shoes and new white pants. I wired him suggesting that the next time he went to the mountain in the rain he ought to put on a pair of overalls and go barefooted. This advice held him down for several days, but in a short time he was lambasting again.

We got the road built as soon as we could. First a good graveled highway and later a hard-surfaced road. After that first dedication, people could travel to the mountain by automobile. Borglum had a habit of dedicating the mountain about once every year. I attended a number of these dedications. The last one I attended was when he had President Franklin D. Roosevelt come out and dedicate it. There was a tremendous crowd attending on that occasion. I thought then that now at last the mountain was properly dedicated, and that it would not be necessary for me to attend any further ceremonies of this sort. I never did. But I have visited Mt. Rushmore upon many occasions since then and always enjoyed the visit.

On one occasion when Mr. Borglum was in Washington urging the necessary appropriation to continue the work, he arranged with President Roosevelt for a meeting in the executive office, to which he invited all senators representing states carved from the Northwest Territory. Most of the senators attended. Borglum was the orator to make the speech to the president. He was a good orator. He was then stressing the importance of carving a short history of the United States on the mountainside. He said he intended to carve this history in four languages, English, Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit.

Senator Tom Connally, of Texas, thought it was time for a question. He blurted out, “What in the world do you want to cut it in Sanskrit for? Nobody reads that.”

Borglum turned on Tom with a withering look of scorn. Striking a dramatic pose, he said, as nearly as I can now recall: “Sir, Mount Rushmore is eternal. It will stand there until the end of time. This age will pass away and all its records will be destroyed; 10,000 years from now all our civilization will have passed without leaving a trace. A new race of people will come to inhabit the earth. They will come to Mount Rushmore and read there the record that we have made. If that record is written on that immortal mountain in four languages, those people will not have the difficulty in reading our record that we had in figuring out the hieroglyphics of Egypt.”

Gutzon Borglum never lived to carve that history on the mountainside, but he had the vision. No other man has ever had the perspective to carve such gigantic figures and make them look natural to the human eye from any spot below. Several times I climbed into the basket and rode up the cable to the mountaintop and inspected the carvings at close-up view. The close-up view is disappointing. You cannot see the face of Lincoln when you stand on his lower eyelid; you cannot see Washington while walking back and forth on his lower lip. It takes a genius to figure out the proper perspective so that the carvings will look right from the point from which the human eye beholds them. Gutzon Borglum was that genius.

On one occasion I was visiting him at his studio at the foot of the mountain. We were out on the porch looking up at the mountaintop, where a number of men were working on the carvings. He said Washington wasn’t right. His head did not sit right. He was going to turn the head around a little. I asked him how in Sam Hill he was going to turn Washington’s head around in the solid granite of the mountain. He took me into his studio and showed me his model, pointing out how he would chisel off a little here and a little there. I could not see his point at all. But a few months after that, I was up there again, and Gutzon Borglum had turned the head of Washington around.

Those of you who have visited our National Capitol and looked at the bust of Abraham Lincoln have seen a marvelous reproduction. Gutzon Borglum’s Lincoln is, I think, by far the best. Many times have I stood and gazed upon that marble bust and marveled at its beauty. No other artist in all the world could take a piece of cold and expressionless marble and reflect there so well the likeness of the face of America’s best beloved — the most beautiful face in all American history.

Upon one occasion Mr. Borglum and I were visiting in the Rotunda together. We stood before the bust of Lincoln. I complimented the sculptor, as best I could, on his work, and he told me that the Lincoln bust was the work of a lifetime. Before undertaking the task he had spent years in studying the life of Lincoln; he had read every book that had been written about Lincoln; he knew Lincoln and had his likeness emblazoned upon his own memory before he undertook to produce the likeness in marble. Those of you who have made a pilgrimage to Gettysburg have seen the memorial there erected by the citizens of North Carolina in honor of their heroic dead. That monument is a group of soldiers cast in bronze — and it was created by Gutzon Borglum. Everyone who has ever looked at that monument returns for a second look, and then for a third. It is by all odds the most attractive memorial on that historic field.

The best view of Mt. Rushmore, I feel, is the one seen as you look through the tunnel, as you drive up the paved highway toward the mountain. As you approach the entrance of the tunnel, looking through it, you see the four heroic figures as if they were encased in a picture frame. As one looks at Mt. Rushmore from any angle, it is awe-inspiring. I have never talked with anyone who has not admitted that his heart beat faster with patriotic pride as he gazed upon that heroic shrine.

People who claim to know tell me that Mt. Rushmore is not subject to erosion; that its granite is everlasting; that a thousand years of winter snows and winter storms, and a thousand years of summer rains and summer suns will leave no mark upon it. Generations hence, when we who had our troubles with Mr. Borglum are forgotten, the name of the man who carved those noble figures in the granite will be remembered. Gutzon could be a little difficult at times, but there was greatness in him.

Featured image: Borglum with his model of Mr. Rushmore (Library of Congress)

The Tragedy of Mallory and Benjamin

Mallory turned the key in the lock and stepped inside. She sighed, exhaling the stress of the past few hours, and glanced up at a handwritten sign on the elevator. Out of Service.

She whined. She groaned. But she had to take the stairs, so she slipped off her heels and did so.

Six awful, stupid, poorly designed, dumb, exhausting flights of stairs later, she unlocked the door to her apartment and, not bothering to change out of her dress, flopped onto the bed.

What an awful first date …

*

She woke to three taps on her bedroom window. She turned — yawning — and gasped.

“Egh!” Then “Oh.” She scowled. “It’s you.”

It scraped the window in an upward motion and stared at her with big moon-yellow eyes.

“No,” Mallory said.

The creature half-slithered, half-crawled onto the window ledge. “Please,” it said in a voice that sounded as if it came from an old radio. “It’s a wonderful play, and you’re one of the main characters!”

“I don’t care,” Mallory said. Her fingernails dug into a pillow.

The creature scraped the window again.

Mallory thought maybe she would lift the window, if only to give him a solid punch in the face, but decided against it. He was tricky. He would get in. And then she’d be awake for hours searching for him in the apartment, trying to get him out.

He tapped the window again. She smirked. Relaxing her fingers, Mallory put a hand up to her face and bit one of her fingernails off. The creature’s long claw (what he’d tap-tap-tapped on the window with) broke off. He howled and descended down the brick, down and away from her apartment.

Mallory wagged her finger around in pain. Blood was all over the bed sheets.

Half of her nail had been ripped off.

“Damn it,” she said.

*

Mallory tossed another piece of popcorn into her mouth and sipped her wine. On TV, an evening-television self-help program (one of those hosted by a Dr. Something who wasn’t, actually, a doctor) featured a middle-aged woman who had been recently widowed. “You have to confront it,” the doctor said. “Meet it in the flesh and acknowledge it, let it be your friend rather than your enemy. Fear can consume you, will consume you, if you let it.”

“But it’s just — that — voice, it’s so logical, I know the next morning I’m going to wake up and he’ll be there. But then he’s not,” the middle-aged woman said.

“Yes,” the doctor said, nodding. “Fear’s language is rational and logical, isn’t it? And worse yet, the voice always sounds suspiciously like your own. It’s a parasite. It feeds on pain.”

The middle-aged woman began to sob. “What can I do?”

Mallory blinked and shut one eye. She blinked again. Her contact lens was dry. She glanced up, dragged the lens down to the white of her eye and pinched it. She put the lens in her mouth, swished it around as if it were mouthwash, and put it back in her eye.

“… if you don’t, it’ll still be there, biding its time until it can combust. Because it will one way or another.”

The studio audience clapped, and the program went to a commercial. She muted it.

At her window, a little earlier than usual, she spotted Mr. Gravespeare. He had the Laughing Face on. She turned away from him. “Hmph.” His Laughing Face twisted into a Weeping Face, and both of his moon-yellow eyes darkened a shade.

“You won’t get any sympathy from me,” Mallory said. “Those are just masks.”

“I wrote an entirely new scene to the play,” Mr. Gravespeare said with a flourish of his claws. “Would you like to hear it?”

“No.”

“It’s an epilogue. And everyone loves epilogues!” Features warping, twisting simultaneously, the Weeping Face became the Laughing Face again. “It’s a Saturday, and the girl, Mallory, woe-stricken, heartbroken, and oh-so-sad, cancels the date she had scheduled that night. Oh, the misery!” he cried. “Oh, the pain!” he wailed. “Guess what she does instead?”

“Go away!”

“She gorges herself with wine, butters her popcorn with tears, turns on the programs that remind her most of the noble Benjamin, our beloved hero in this story, and lets the people in the television feel the loneliness so she doesn’t have to —”

Mallory got up and stormed out of the bedroom. It was time to get curtains for that window.

“Wait!” Mr. Gravespeare shouted after her. “You’re going to miss the best part!”

*

Under the store’s fluorescents, in wine-stained pajamas, and her hair in a bun, Mallory picked up and flung down every plastic-wrapped package of curtains on the shelf. She hated the selection. Everything was terrible and stupid. And her contact lens was getting dry again. She made herself take a breath, inhaling long and slow, exhaling slower and longer. She glanced up, dragged the contact lens to the white of her eye, pinched it, pulled it out, and put it in her mouth. She swished it around for a few seconds.

“Still doing that, huh?”

Mallory turned with her tongue out and her fingers poised to take the contact. Her vision was half-blurred, but she recognized Benjamin’s voice.

She chuckled, no humor in it, and put the contact back in her eye. He’d gotten a haircut. And his shirt was ironed. And that was a new watch — wasn’t it?

She became hyper-aware of the wine stain on her pajamas (as well as the pajamas themselves) and grabbed the first package of curtains she touched.

You have a motorcycle jacket on, steel-toed boots, and you look hot as hell, she told herself. “Hey. What’re you doing here?”

“Getting curtains, actually,” he said.

“Yeah? How come?”

“Sun’s waking us up in the morning.”

Us? “It’ll do that.”

“You?”

“Hm?”

“Sun waking you up in the morning too?”

“Oh. No. There’s this creepy, undead monster-thing that crawls up the side of my apartment at night and taps on my window. He’s always begging me to let him in so he can show me this play he wrote? … So, anyway, my battle-plan is curtains.”

Benjamin’s mouth dropped. Neither of them said anything for a moment. And then he cracked up.

“Wow,” he said, wiping his eyes. “All right. Well, um, good luck with that.” There was another silence. “It’s great to see you. You look — um —” Mallory raised an eyebrow. “Like you’re having a relaxing evening.”

Mallory nodded. She glared. She didn’t blink.

“They messed up the sides again,” she said, referring to his haircut. Curtains in hand, she power-walked to the nearest checkout lane. She still didn’t bother to read the packaging on the curtains as the cashier scanned them. They were ruby red, quite long, and very wide.

*

Mr. Gravespeare skittered spiderlike up the brick exterior of Mallory’s apartment and peered around the building at the entrance. One big moon-yellow eye studied her as she stumbled up the stoop. His face shifted from Laughing to Weeping and then to Laughing again. She didn’t remember to lock the door.

Gravespeare skittered farther up the building to Mallory’s window. Like a mechanic, he unscrewed one of his moon-yellow eyeballs from its socket and set the eye on the window ledge, facing the bedroom.

Mallory stepped into her apartment, shut the door, and then slid down to the floor with her face in her hands. Gravespeare nearly giggled with joy; what juicy, theatrical images she was giving him! Furthermore, in her despair (it could’ve only been a result of bumping into Benjamin — how much more perfect could this get?), she forgot to lock that door too.

Gravespeare snatched his eye from the window ledge and spun it back into its socket. He skittered down the building, claws clicking against the brick.

He paused for a minute to let passersby clear the area. Then he scuttled, slithered, and stretched his way to the front of the apartment and up the stoop, and in one fluid movement, Gravespeare turned the doorknob. He squeezed through the crack in the door, and continued into the foyer.

Gravespeare came to the elevator and read the sign (Laughing — Weeping — Laughing again). Out of Service. He hopped three feet up in the air, yanked the elevator door open, held it there, and dropped feet-first into the elevator shaft.

With one claw he grabbed hold of a steel column, hung from it for a second, swinging, and then scuttled up the elevator shaft — up-up-up.

At the sixth floor he pried open the elevator doors and vaulted himself into the carpeted hallway. He was so jittery with excitement (he would be performing soon!) he didn’t notice the young boy come out of an apartment just ahead, dragging a trash bag. The boy stared at him.

“What’re you doing here?”

Gravespeare put on the Weeping Face. “I’m about to debut a new play,” he said, his voice in several octaves at once.

“I hope it’s better than the last one,” the boy said.

Gravespeare might’ve scowled, if he could — that comment was certainly unjustified, if not also rude.

*

Mallory washed her face and changed into different clothes. She wasn’t going out again — and changing hadn’t exactly made her feel better. Actually, changing had made her feel worse. It was too late, now, to pretend she was having anything more than “a relaxing evening.”

From the bathroom, Mallory heard the rip of plastic being torn. “You didn’t get a curtain rod?” a voice said — a familiar, haunting voice. “Oh, well. The show must go on!”

Mallory pulled and twisted at the bathroom-door doorknob. It was stuck — no, it wasn’t stuck. It was being held.

She gripped the doorknob and turned it with all her strength. It wouldn’t budge.

“Hold on, now,” Gravespeare said. “I have to get everything set up.”

Gravespeare made his stage by dividing the sitting room from the kitchen. One arm stretched far and long to hold the bathroom door shut as the other fastened the curtains to the wall with claws he’d unscrewed from his toes. The sitting room would be where Mallory could sit during the play if she didn’t make a fuss. The kitchen, with the curtains drawn, would be his performance space.

“Let me out!” Mallory screamed.

“So you can destroy my stage?” Gravespeare said. “I don’t think so.”

“This is my apartment!”

“And you lending it to me is kind, given the circumstances.”

“Please, this is the worst time to do this.” Her heart thumped in her chest.

“What happened, dear? Tell me while I make the finishing touches.” Mallory began to cry. “No, no, no! Wait for the show, wait for the play! Don’t shed all your tears just yet. They’ll come soon enough!”

“I don’t want — I don’t want — ”

“You don’t want what, dear?”

He finished fastening the curtains and then drew them aside one at a time, pinning the midsections to the wall with two kitchen knives. He was out of toenail-claws.

“I don’t want to think about him!”

“Who? Benjamin?” The curtains set, he let that arm contract. “But dear, this play is all about Benjamin. And you, of course! You’ll just have to think about him!”

“No,” Mallory cried. “Please.”

Gravespeare stretched his neck until it was as thin as a rubber band, reaching his head toward the bathroom door. “After the play, I’ll go,” he whispered, head beside the door. “If I let you out, will you promise to be as sweet as I know you are and let me do the play for you, no fuss?”

“I’ll kill you if you let me out!” she said, and pulled and twisted and tugged at the doorknob.

“Tsk, tsk, tsk,” he said. “Fine.” The rest of Gravespeare’s body inched, like a centipede, toward his head.

Gravespeare put a claw in front of the bathroom door and scratched an X in the air. The door disappeared.

Mallory’s first instinct was freedom. She hurled herself forward, struck something, and stumbled backwards. She stared at the space where the door had been — when she set her hand there, she could feel the wood. He’d made the door transparent.

Crouched, with skin like volcanic rock and dull, jagged spikes at the shoulders, elbows, and knees — a face at Laughing, and two big moon-yellow eyes — Gravespeare cocked his head to one side, staring at her.

Mallory lifted her hand to her face and barred her teeth. His face changed to Weeping. Heart thumping wilder and wilder, she bit down on a fingernail and ripped half of the nail off. Gravespeare howled in pain and cradled his hand against his ribs. Blood dripped onto the tiles in the bathroom, and Mallory lifted her other hand to her face.

“No, no, no!” Gravespeare said. “Is emotional pain so much worse than physical pain? Come, now, don’t do this!”

She bit the fingernail, and this time, since she was already in pain, tore the whole fingernail off. Blood leaked steadily onto the tiles like a low faucet drip, and Gravespeare howled and howled and howled. His hold on the doorknob loosened. Suddenly his head began to spin. Mallory readied the next nail, grinning in the ecstasy at the pain, when the spinning ceased, and instead of Gravespeare’s head, it was Benjamin’s.

“Like you’re having a relaxing evening,” it said in Benjamin’s voice.

Mallory’s hand fell to her side.

“Still doing that, huh?”

Her breathing came slower and slower, her heart thumping at wider and wider intervals.

“Sun’s waking us up in the morning.”

They’d only dated for five months. Why had she fallen in love with him, why had she let him in? With steel-plated lies he’d built a bridge to her heart, and even though the bridge had been burned, she was still treasuring the ruin.

“Well, good luck with that.”

Her lips parted. She remembered the night — it was so many years ago, the memory had been buried for a while — after her dad had left. She’d met Gravespeare that night. She remembered thinking then that he was rather an amusing, if not also awful, actor.

Gravespeare’s head started spinning again. It paused on the Weeping Face.

“I’m not an awful actor,” he said.

Her eyes puffy and pink, her upper lip dotted with dark blood, and eyeliner smeared across her cheeks, Mallory smiled.

He changed to the Laughing Face.

“Will you listen to my play?”

Mallory inhaled. She exhaled.

*

Mr. Gravespeare, a top hat on his head tilted over one eye, struck a grandiose pose.

“The Tragedy of Mallory and Benjamin,” he started. “The players — myself. The characters — the heroic, handsome, slightly hard-of-hearing Benjamin.” (Mallory giggled.) “And the self-deprecating, somewhat bow-legged, pooper-of-parties, Mallory Winters. The play begins outside a noisy Manhattan bar, where Benjamin is outside smoking a cigarette, his hair coiffed and trimmed neat on the sides …”

He truly was an awful actor. But there was a charming quality to that. After the play, he bowed, and she gave him a standing ovation. As he left (once he’d unfastened the curtains, folded them up the way they’d been in the packaging, and put the kitchen knives back in the drawer), Mallory thanked him.

“I hope there won’t be any — well, um, any future performances anytime soon.”

The Laughing Face became the Weeping Face and then changed back to the Laughing Face again. Upside-down, hanging from the ceiling in the hallway, he said, “I am but a humble actor, not a fortune teller. But I am sure there will be future performances. Not of this play, of course. This play, my dear Mallory, is finished.”

Gravespeare scuttled across the ceiling to the elevator, popped it half-open, dropped into the shaft, and paused midair at the first floor. He wrenched the elevator ajar and flew like dark-gray smoke out the front door into the night. He fled like this because he had somewhere to be — and soon. There was a new play, he was sure, just a few blocks down.

News of the Week: Expensive Peanuts, Free Tacos, and Spiders You Can Actually Eat

MetLife Nixes Peanuts

I don’t know how the Peanuts gang ended up as the spokespeople (spokescharacters?) for an insurance company 30 years ago, but it’s going to be sad to see them go. MetLife has decided to end their relationship with Charles Schulz’s popular creations, for which they pay over $10 million a year to license. The company is going to be rebranding itself as it spins off its individual life insurance plans in the U.S. in 2017.

In related news, rebranding is one of my least favorite words ever.

Thanks, Francisco Lindor!

Even though the World Series is currently tied at one game apiece, there are already winners, and they are us. Because Cleveland Indians shortstop Francisco Lindor stole a base in game one on Tuesday night (sorry, Cubs fans), everyone gets a free taco at Taco Bell next Wednesday, November 2, between 2 and 6 p.m.

If a player steals a base in the #WorldSeries, America gets free #DoritosLocosTacos. Who will be our taco hero? https://t.co/ZxGL0QoJRB pic.twitter.com/cWIxXGHXbl

— Taco Bell (@tacobell) October 20, 2016

This promotion was based on stealing just one base in the entire World Series? Taco Bell must really love to give away tacos.

Is Coupon Pronounced “Koopon” or “Q-pon”?

It’s “koopon.” Hey, that was easy!

Well, okay, there’s more to the story. Over at Slate they’re debating whether coupon should be pronounced “koopon” or “Q-pon” (they write it out as “cyoopon,” but that’s just confusing). I hadn’t even heard of the second pronunciation until a friend of mine who travels the country selling coupons told me that he encounters many people who pronounce it “Q-pon” and it drives him crazy. I thought that it might be a regional thing, different areas of the country saying it a different way like we do many other words, but I don’t think that explains it. Coupons.com did a poll five years ago, and 57% of the people said they pronounce it “Q-pon.” I don’t know any of those people.

The writer of the Slate piece says “Q-pon.” His wife says “koopon.” Wars have started over disagreements like this.

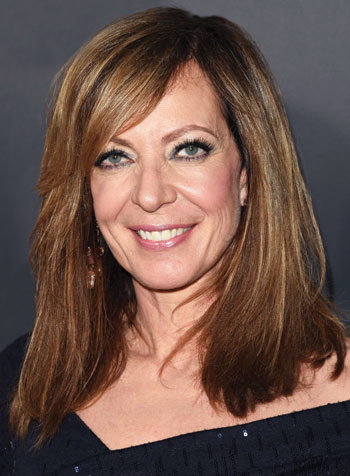

I’m So Glad We’re Gonna Spend More Time Together

One of my favorite childhood memories is watching the Saturday-night lineup on CBS in the ’70s. It’s hard to convince younger people today, when Saturday-night network television is for repeats and movies and maybe some news shows, that the night used to be worth staying in for. All in the Family, The Bob Newhart Show, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and The Carol Burnett Show all aired on one night and on one channel. Pre-VCR, who would want to go out and miss that lineup?

Burnett, who was interviewed for our upcoming January/February issue, is coming back to television. She’ll star in a new ABC sitcom produced by Amy Poehler. It’s about a family who gets to buy a great house really cheap, but on one condition: They have to live with the woman (Carol Burnett) who currently owns the house.

Click Your Heels Together Three Times …

What happens when an iconic movie prop is decaying and you don’t have the money to repair it? You start a Kickstarter.

That’s what the Smithsonian did. They wanted to restore Dorothy’s ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz, so they started a crowdsourcing campaign. They ended up raising more than $300,000! They’re also raising money to restore Ray Bolger’s Scarecrow costume from the movie.

They actually made as many as 10 pairs of ruby slippers for the movie. One pair was stolen, and another pair was sold at auction. These Smithsonian shoes are the ones Judy Garland used the most in the movie, especially in the dance sequences.

RIP Kevin Meaney, Bobby Vee, Kevin Curran, Kathryn Adams, and Pete Burns

I can still remember, vividly, Kevin Meaney’s HBO standup special in the ’80s. It was one of the first things I ever watched on cable, and some of his lines really stick in my mind: “That’s not night!” and “We’re big-pants people!” (There’s another line from the special that’s also really memorable, but I can’t repeat it on a family website.)

Meaney passed away last Friday at the age of 60. Many comics have penned tributes to the influential comedian, including Louis C.K.

Bobby Vee, who passed away Monday at 73 will be remembered for the song “Take Good Care of My Baby,” but he had another tie to history. In 1959, at the young age of 15, he filled in at a concert in Moorhead, Minnesota, after Buddy Holly, J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, and Ritchie Valens were killed in a plane crash.

Kevin Curran was a producer and writer for The Simpsons from 1998 to 2015. He was also a producer/writer for Married…with Children, Unhappily Ever After, and The Good Life, and for many years was a writer on Late Night with David Letterman. In fact, he wrote Letterman’s very first Top 10 List, “10 Things That Almost Rhyme with Peas.” He won three Emmys for The Simpsons and three for Late Night.

Curran was just 59 years old. He passed away Tuesday after a long illness.

Kathryn Adams appeared in such movies as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Saboteur, If I Had My Way, and The Invisible Woman, but she quit show business in 1946 to focus on her family and her husband, Leave It to Beaver’s Hugh Beaumont. She passed away this week at the age of 96.

You might not remember the name Pete Burns or his band Dead or Alive, but their most famous song has had amazing lasting popularity since its release in 1985. It was even used recently in a commercial for a Candy Crush game.

Burns died of a heart attack at the age of 57.

This Week in History: Black Thursday (October 24, 1929)

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 is usually referred to as “Black Tuesday,” but the events that led to the stock market disaster and the Great Depression actually started on Thursday of the week before. To make things even more confusing, Monday of that week is called “Black Monday.”

This Week in History: Statue of Liberty Dedicated (October 28, 1886)

Saturday Evening Post archive director Jeff Nilsson has a nice piece on our national symbol of freedom, a gift from the people of France.

This Week in History: Dr. Jonas Salk Born (October 28, 1914)

Salk’s injectable polio vaccine was released to the public in 1955. A few years later, medical researcher Albert Sabin came up with the oral version.

Spiders Aren’t as Scary If You Can Eat Them

In the past, I’ve given you various recipes for Halloween, including bat wings, pumpkin muffins, ghostly milk shakes, and fingers from a witch. This year, I thought I’d focus on arthropods.

Here’s a recipe for Spider Chocolate Chips Cookies, and here’s one for Oreo Spider Web Cookie Pizza. This recipe is for Scary Spider Web Eggs, and it’s so odd-looking that it might just freak people out.

I live in New England, born and raised, but I’ve never heard of New England Spider Cake. But apparently it’s a thing, and here’s the recipe. It’s a creamy cornbread you top with maple syrup.

Note: It has nothing to do with spiders.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Halloween (October 31)

Here are some of the great Halloween covers we’ve done over the years. (My favorite is the November 1, 1958, cover by John Falter.)

National Alzheimer’s Awareness Month starts (November 1)

Check out the Alzheimer’s Association website to find out how you can volunteer and find walks in your area.

National Novel Writing Month starts (November 1)

Or NaNoWriMo for short. I’ve never attempted to write a whole novel in a month, but it can be done.

The Little Yellow Flower That Turned to Gold

Originally published on July 7, 1945

Originally published on July 7, 1945

Money in your own back yard is the stuff dreams are made of, but George A. Campbell proved to his neighbors of Bigtimber, Montana, that such dreams can come true with a gratifying bang. For years, a small plant with tiny yellow flowers had been springing up in abundant patches in their gardens, fields, sheep corrals, and over the mountainsides. It came to be known as “that cussed poisonous weed,” for it was so fatal to chickens and turkeys that ranchers had to destroy every trace of it that appeared near their poultry houses.

Then George Campbell began to wonder if there mightn’t be some use for this weed. The ranchers pooh-poohed the idea; nevertheless, he took a bouquet of the dirty yellow flowers to a chemist.

“That’s henbane,” the chemist told him. “Find much of it? It’s worth a pretty penny on the market — a dollar and a quarter a pound, dried.”

Henbane, it turned out, is much in demand today for medicinal purposes. More properly called Hyoscyamus niger, it is the source of several poisonous drugs, including tincture of hyoscyamus and hyoscine, that are useful in the treatment of a number of ills.

Campbell hurried home and worked day and night in the henbane patch on the mountainside. The ranchers thought he was crazy, especially when he hired every available man, woman, and child in the community to pick henbane for him at eight cents a pound. On top of this, he hired another man during the season — June, July, and August — to help put up drying racks, and he gave 320 days’ work to women who averaged from three to seven dollars a day stripping leaves and flowers for drying. In all, he spent a pretty penny himself — something between $4000 and $5000 for labor, lumber, and transportation. But he sold 43,000 pounds of henbane at $1.25 a pound. So the profit was pretty too.

That was in 1943, and since then Bigtimber has enjoyed a new prosperity. School kids make enough in one season to send themselves through college or help stock a ranch. Enough henbane has gone to seed each year so that, thus far, the supply has been good. Apparently the plant does not lend itself to cultivation, but grows profusely in old sheep corrals, waste grounds, cemeteries, and in the mountains. No two reference books agree about the states where it may be found; evidently the full extent of its growth has not yet been determined. You may even have a few thousand dollars’ worth of it spreading itself around your own neighborhood.

July/August 2016 Limerick Laughs Winner and Runners-Up

It feels like a hundred and three!

And we’re both just as parched as can be.

We’re panting and moaning,

Perspiring and groaning…

So why are we drinking hot tea?

Congratulations to Guy Pietrobono of Washingtonville, New York! For his outstanding limerick, he wins $25 and our gratitude for this funny and entertaining poem describing Billboard Painters (above) by Stevan Dohanos. You can enter the Limerick Laughs Contest for our next issue of The Saturday Evening Post through our online entry form.

Guy’s limerick wasn’t the only one we liked. In nor particular order, here are some of our other favorite contest entries:

When the heat is uncompromising

And the work is ever-perspiring.

With the drink that you pour,

It is hard to ignore

That there’s truth in some advertising.—S. Pavelich, Grand Blanc, Michigan

Two painters named Willy and Fred,

Rode up in a truck that was red.

Old Fred should have learnt

That his head would get burnt

If his hat was not up on his head.—Tom Glatting, Chillicothe, Ohio

“Imagine us both in the shade

Sipping GALLONS of pink lemonade …”

“Imagine instead

That we’re working here, Fred,

‘Cause on Friday I’d like to get paid!”—Guy Pietrobono, Washingtonville, New York

I’m thinkin’ that drinkin’ this potion

Might make me go weak with emotion.

Up here on this deck,

It’s hotter than heck.

A refill? You’ll have my devotion.—Rebekah Hoeft, Redford, Michigan

The sign was for selling AC.

One painter explained it to me:

AC really cools

By transferring joules.

And a jewel of a painter was he.—Phillip T. Ross, Indianapolis, Indiana

Think back, now, to winter’s big chill,

And the snowball you rolled down the hill.

This heat wave won’t last,

It soon will be past,

And then you’ll miss summer, you will!—Grace Bates, Ft. Wayne, Indiana

It’s hotter than what it reads there,

And that big fan ain’t blowin’ cool air.

It sure would be nice

To sit on the ice

And pretend to be Big Papa Bear!—Dolores M. Sahelian, Mission Viejo, California

Of all the unfortunate luck,

Hot weather had actually struck.

Poor Robert and Casey!

If only the AC

Was working inside their own truck.—Neal Levin, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

Outdoor work that is done in the sun

Isn’t close to a job you’d call fun.

When the heat is so cruel,

Try to keep yourself cool

So not you, but the sign, is well done.—Thomas Eveslage, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Democracy in Suspense: Awaiting Election Results with Guns Drawn

Americans were shocked when, during the third presidential debate on October 19, 2016, GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump refused to say that he would accept the results of the presidential election, which he had long claimed would be rigged. Belief in the sanctity of popular elections and acceptance of their outcome are core principles of democracy. We have faith in the electoral process, even if we don’t like who gets elected.

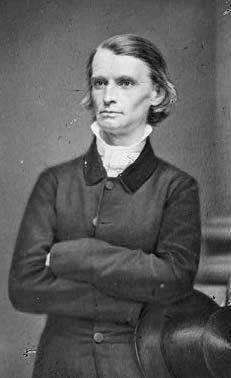

But Americans haven’t always been willing to accept election results. In the 1860s, weeks before any votes were cast, some people were ready to disavow an election: Southern politicians planned to take their states out of the Union if a Republican were elected. As soon as the news arrived of Lincoln’s victory in 1860, the South Carolina Assembly passed a resolution “To Call the Election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President a Hostile Act” and declared it was leaving the union. Ten more states followed its example.

But 1860 wasn’t the first time Americans prepared to defy the national will.

Four years earlier, the 1856 election was a three-way contest between Republican John C. Fremont, Democrat James Buchanan, and Millard Fillmore, candidate of the Native American/Know-Nothing Party. Emotions ran high during the campaigning; in Baltimore, for example, the election had prompted “continued and violent rioting during the afternoon and evening,” according to the Post.

A fierce engagement took place between the Democrats of the Eighth Ward and the [Native]Americans of the sixth. Each party was provided with muskets and cannons, and the fight was kept up for over two hours. Some fifty persons were wounded, including a large number seriously. In the Second Ward, the Democrats drove off the Americans. The Fourth Ward Americans came to the rescue, and after a prolonged and fierce fight, retook the polls and drove the Democrats off. The fight lasted over an hour. One man was killed and thirty wounded, several fatally. [November 8, 1856]

The newly formed Republican party opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories. It promoted the idea of a “Free Society” without slavery or control by an aristocratic class. This policy won Fremont broad support in the North, but the hatred of many in the South, where political leaders assumed Fremont’s election would doom slavery and the southern economy. Through their newspapers, Southerners vilified the North and its ideas of a Free Society without slavery or a planter aristocracy.

In October, just one month before the election, the Post ran an article titled, “The Union: Shall It Be Preserved?” It alerted readers to the secessionist movement in the South, which was stirring bitter resentments against the North and the federal government.

We allude to those Disunion doctrines now openly avowed and advocated by the Secession press in the slaveholding States! These Secession editors evidently are striving with all their might to reconcile the Southern mind to the idea of practical Disunion. They are doing all in their power to stir up bitter feelings against the Free States as Free States. Not content with warring against a particular party, they are warring against the structure of Free Society itself.

Do our Southern readers ask for the proof of this? — let them read the following. The Muscogee (Ala.) Herald says:

“Free Society! we sicken at the name. What is it but a conglomeration of GREASY MECHANICS, FILTHY OPERATIVES, SMALL FISTED FARMERS, and moon-struck THEORISTS! All the Northern, and especially New England States are devoid of society fitted for well-bred gentlemen.”

The Virginia South Side Democrat — Democrat, indeed! — says: —

“We have got to hating everything with the prefix FREE, from free negroes down, and up the whole catalogue — FREE farms, FREE labor, FREE SOCIETY, FREE will, FREE thinking, FREE children, and FREE schools, all belong to the same brood of damnable ‘isms.’ But the worst of all these abominations is the modern system of FREE SCHOOLS. The New England system of free schools has been the cause and prolific source of the infidelities and treason that have turned her cities into Sodoms and Gomorrahs, and her land into the common resting-place of howling Bedlamites. We abominate the system because the SCHOOLS ARE FREE.”

The Richmond Examiner (Va.) says:

“Repeatedly have we asked the North, ‘Has not the experiment of universal liberty FAILED? Are not the evils of FREE SOCIETY INSUFFERABLE? and do not most thinking men propose to subvert and reconstruct it! … free society in the long run is an impractical form of society; it is everywhere starving, demoralized, and insurrectionary … If free society be unnatural, immoral, unchristian, it must fall, and give way to a slave society — a social system old as the world, universal as man.”

The Post’s editors wanted to alert Northern readers to the South’s plans to defy the government if they disagreed with the results of the election. They cited this 1856 comment from the Baltimore Patriot:

Carolina fire eaters have pointed out in magniloquent sentences, the admirable capabilities of the South for carrying on a defensive war. They have shown how batteries placed in this pass and rifles bristling on that hill side, could work destruction on an advancing foe. Col. [Preston] Brooks has, moreover, advised, in the event of Fremont’s election, that a gallant army of Southerners, equipped with Bowie knife and revolver, shall march in grim procession to Washington, and there seize upon the Government archives and treasury.

(Library of Congress)

Governor Henry A. Wise of Virginia hosted a secret convention of Southern governors in Raleigh, North Carolina in the early fall of 1856. Shortly afterward, the Post ran this item in its October 4 issue.

Preparing for War — The Norfolk (Virginia) Argus states that Gov. Wise has issued through the Adjutant General orders to the commandants throughout the State to thoroughly organize the militia, that it may be qualified “to render effective service whenever Virginia may call for it.”

Fremont lost the election to James Buchanan, but his 1.3 million votes were sizeable enough to keep supporters of slavery worried at the growing support for antislavery candidates.

Four years later, a Republican candidate won the presidency. Southern states promptly withdrew from the Union, and Post readers learned what Governor Wise had been up to in the final weeks before the election:

At a late Union meeting in Knoxville, Tenn., Judge Bailet, formerly of Georgia, stated that “during the last Presidential contest, Gov. Wise had addressed letters to all the Southern Governors — and that the one to the Governor of Florida had been shown to him — in which Gov. Wise said that he had an army in readiness to prevent Fremont from taking his seat, if elected, and asking to co-operation of those to whom he wrote.

—Editorial, February 18, 1860

Featured image: Waiting for the Election Returns in 1856 (Library of Congress)

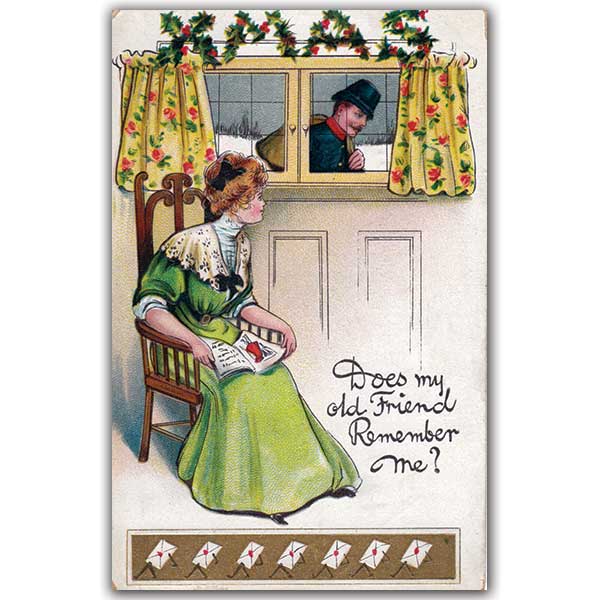

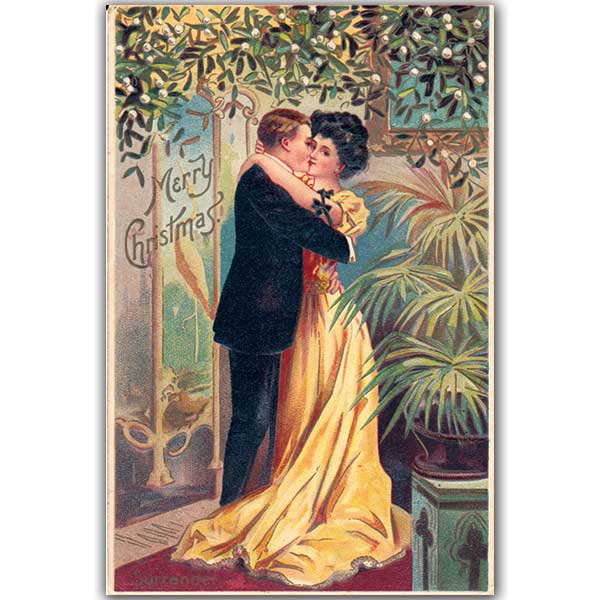

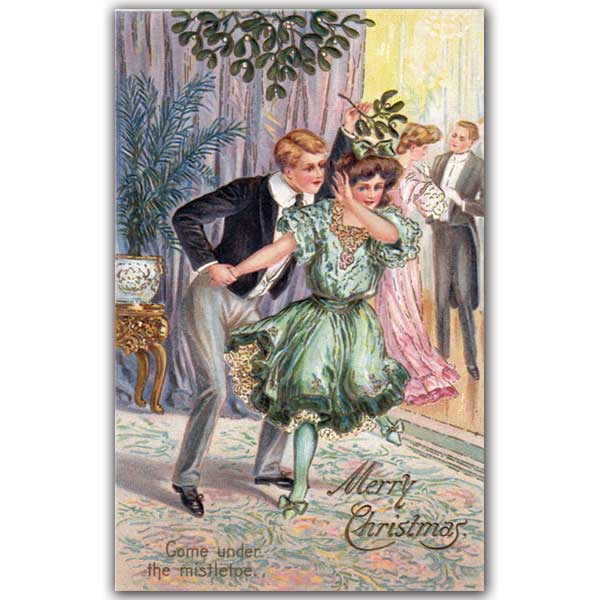

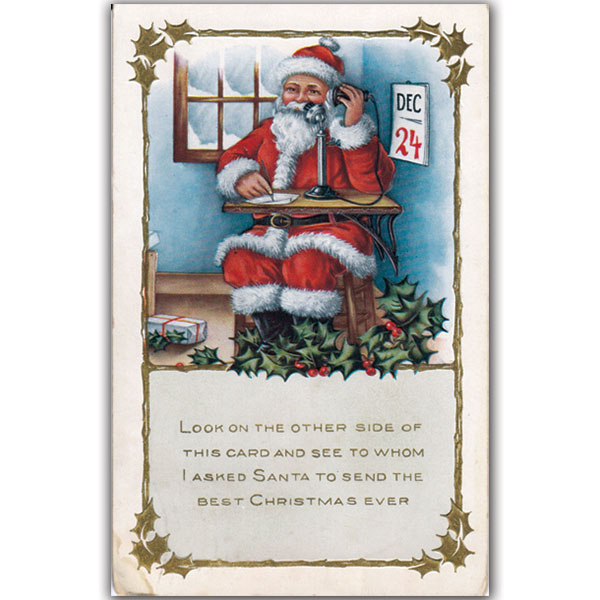

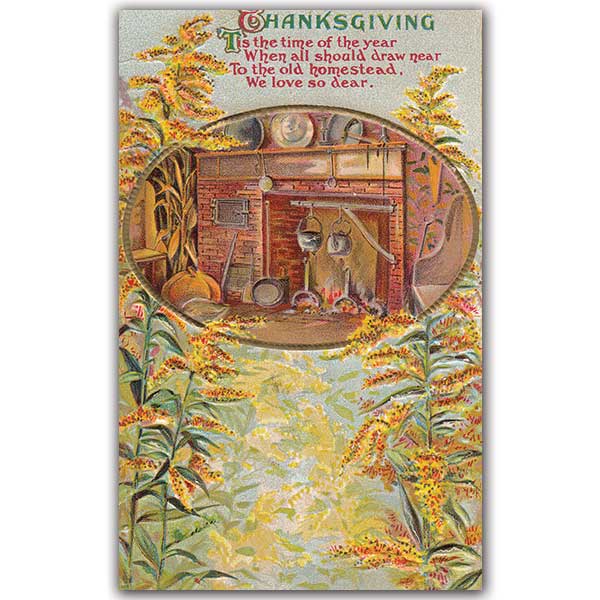

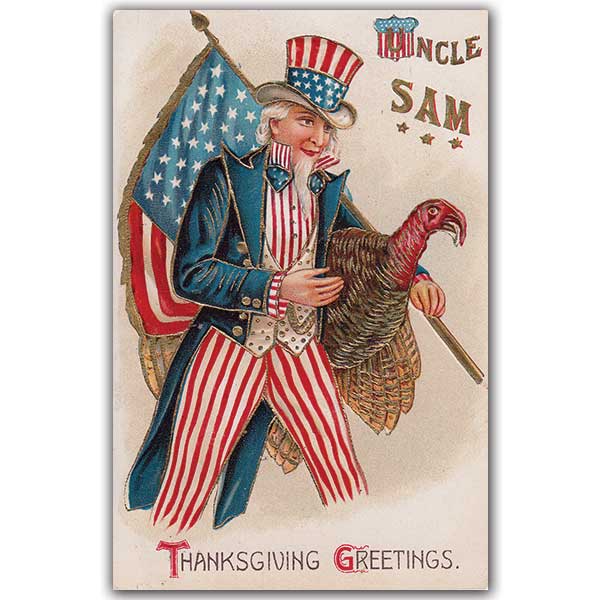

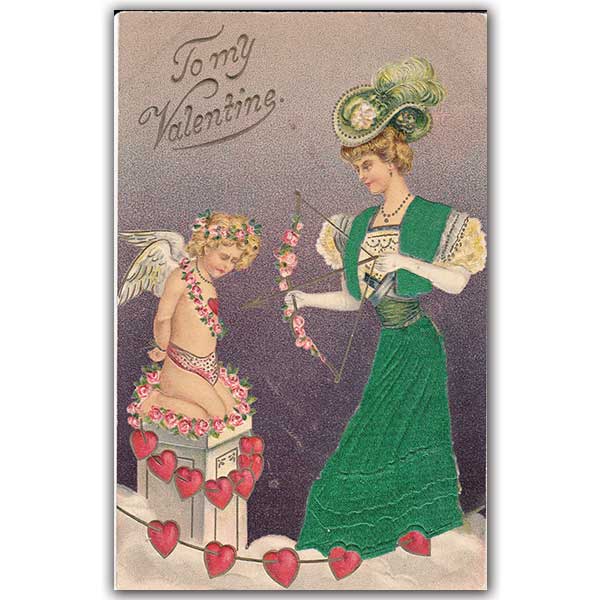

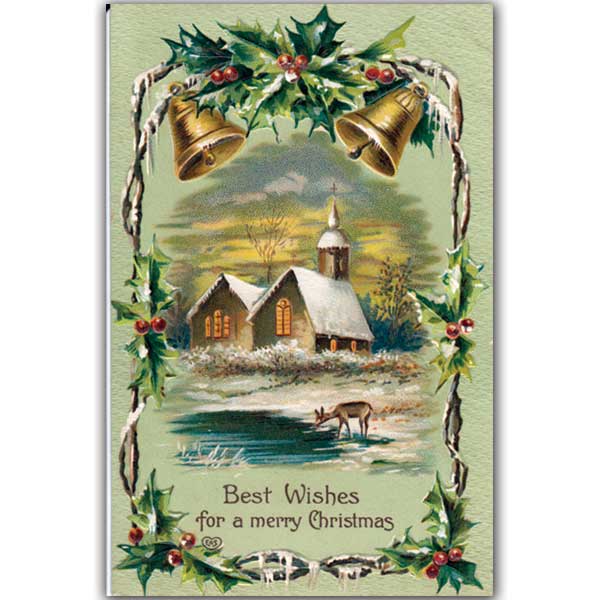

20th-Century Postcard Craze

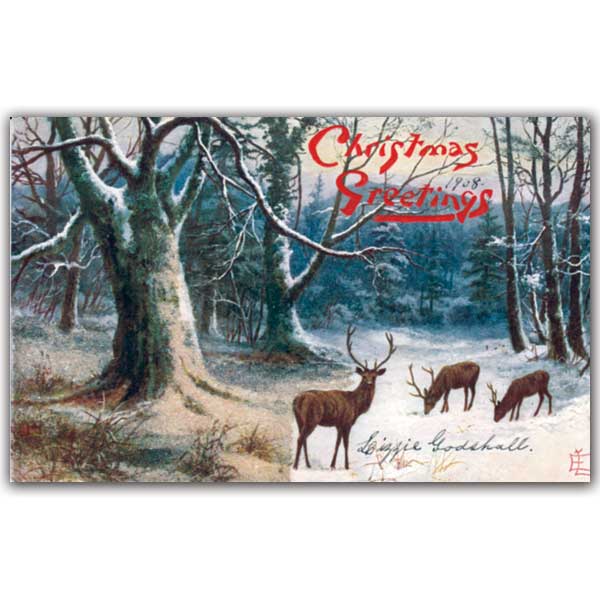

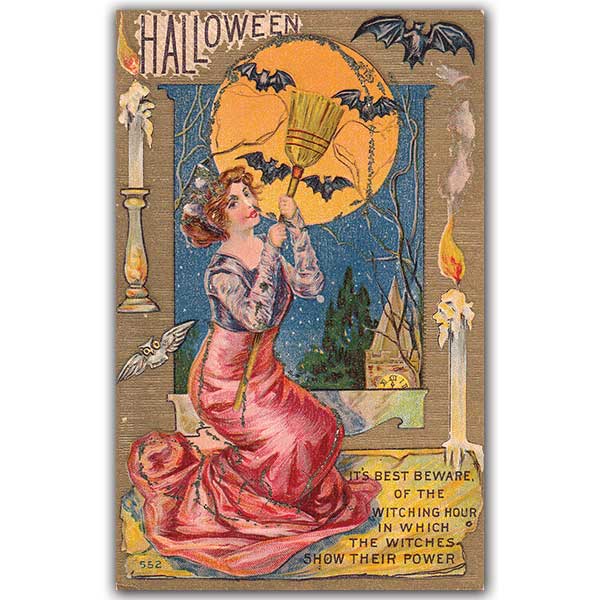

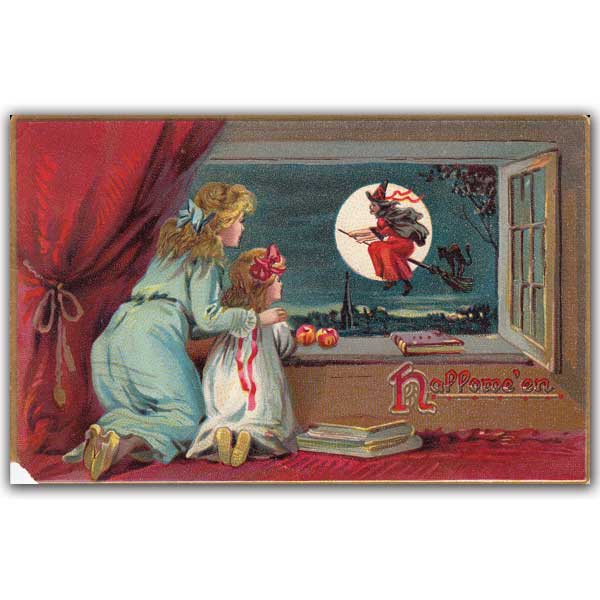

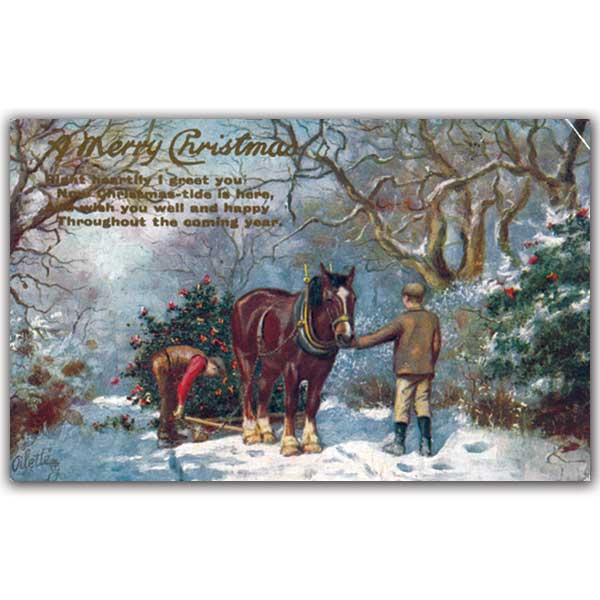

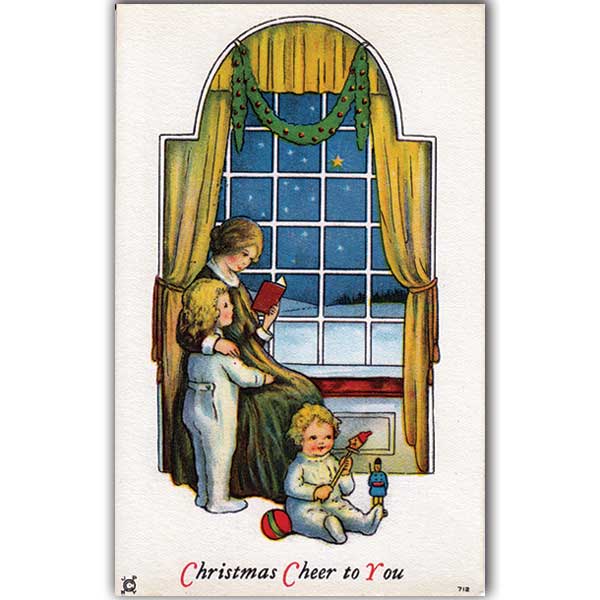

“For a few years in the early 20th century, billions of postcards flowed through the mail, and billions more were bought and put into albums and boxes,” writes Daniel Gifford, author of American Holiday Postcards 1905–1915. “And amid that prodigious output, holiday postcards were one of the most popular types, with Christmas reigning supreme.” Below, Gifford shares a small sampling from his personal collection of early 20th-century holiday postcards.

Click any image to enlarge.

Read more about the “Golden Age of Postcards” by Daniel Gifford in our November/December 2016 issue.

Getting Acquainted with Johnny Carson

By the time of his passing in 2005, he was a legend of the late-night talk show, paving the way for countless other household names of today including David Letterman, Jay Leno, and Joan Rivers. If nothing else, he’s remembered as being the wry, casual antidote to the glitz and glamour that otherwise characterized the scene. Back in 1962, though, he was just three months in as captain of The Tonight Show. Today we look back on the early career of a man who needs no introduction, but who warrants one anyway out of habit: Here’s Johnny.

The Soft-Sell, Soft-Shell World of Johnny Carson

By Edward Linn

Originally published on December 22, 1962

© The Saturday Evening Post

When Johnny Carson first heard he was the leading candidate to succeed Jack Paar as ringmaster of the highly publicized Tonight show, that late-hour NBC marathon of ad-lib humor, adjustable entertainment and adult (and sometimes addled) talk, his initial reaction was, “What do I need that for?”

He was, he explains, just beginning the fifth — and final — year of a daily half-hour ABC quiz program, Who Do You Trust?, and the prospect of tackling one hour and 45 minutes every weekday night was almost too much to contemplate.

His manager prodded him gently for two weeks by pointing out that he owed himself the chance to reach the mass nighttime audience. “I had been offered situation comedies dealing with everything from a bank clerk to a boy disc jockey,” Johnny says, “but the more I thought about it the more I became convinced that Tonight was the only network show where I could do the nutty, experimental, low-key thing I like best.”

Carson has always been a square, low-pressure peg in the round, dog-eat-dog world of show business. He himself likes to point out that he comes not from the Lower East Side of New York but from a Middle West, middle-class background, a situation that not only deprives him of all those “We were so poor that …” jokes but makes him a curiosity among comedians. Nor is he a small, fat or homely waif, searching for love and acceptance in a hostile and dangerous world. He is tall and slim and, at the age of 37, boyishly good looking. Viewing him on a television screen, it is hard to escape the feeling that if Peter Pan had grown old enough to become a naval ensign he would have looked exactly like Johnny Carson.

Since Carson is essentially a comedian who reacts to events around him, his innocent appearance has the added virtue of permitting him to make irreverent and sex-loaded comments without looking as if he really meant them. When Mr. Universe, an awesome tower of muscle, was on Tonight, he proved to have a missionary zeal for converting Carson to the good and healthful life. “Remember, Johnny,” he said earnestly, “your body is the only home you will ever have.”

“Yes, my home is pretty messy,” Johnny replied, looking suitably ashamed of himself. “But I have a woman come in once a week to clean it out.”