Originally published on December 1, 1977

There was such a pretty little fir tree standing in the wood. It grew in a good place, able to catch the sun, getting plenty of fresh air; and many bigger companions grew round about, both firs and pines. But the little fir tree was so impatient to grow: it thought nothing of the warm sunshine and the fresh air; it cared nothing for the village children, prattling away as they gathered strawberries or raspberries. Often they would come along carrying a whole jugful or a string of strawberries threaded on straw, and, sitting down by the little tree, would say: “Isn’t it a pretty little one!” The tree hated to hear it.

“Oh, if only I were such a big tree like the others!” sighed the little tree. “I’d be able to spread my branches right out and from my top see into the wide world! The birds would come and build their nests in my branches, and when the wind blew I’d be able to nod as grandly as they all do!”

Often in the wintertime, when the snow lay glistening white all around, a hare would come bounding along and leap right over the little tree — and how that did annoy it! But two winters went by, and by the third the tree was so big that the hare had to go round it. Oh, to grow, to grow, to get big and old! That was the only nice thing in all the world, thought the tree.

In the autumn the woodcutters always came and felled some of the tallest trees. This happened every year; and the young fir tree, which by now was quite well grown, trembled to see it, for the magnificent trees would fall creaking and crashing to the ground. Then their branches would be cut away, and they would look altogether bare and long and narrow; one hardly knew them again. And they would be laid on wagons, and horses would pull them away out of the wood.

Where were they going? What was in store for them?

When the swallow and the stork came, in the spring, the tree said to them: “Don’t you know where they were taken? Didn’t you meet them?”

The swallows knew nothing, but the stork, looking thoughtful, nodded its head and said: “Well, I believe so! I met lots of new ships on my flight from Egypt, and there were splendid masts on them. I dare say they were the ones — they smell of fir. I can give you news of them — they’ve come out on top!”

“Oh, if only I were big enough to fly away over the sea!”

“Be glad of your youth!” said the sunbeams. “Be glad of your healthy growth, of that young life that’s in you!”

And the wind kissed the tree and the dew shed tears over it, but the fir tree didn’t understand.

Now, at Christmastime quite young trees would be felled, trees which often were not even as big or as old as this fir tree which knew neither peace nor rest but was forever wanting to push on. These young trees — and they were the nicest ones of all — were always left with their branches on. They were placed on wagons, and pulled off out of the wood by horses.

“Where are they going?” asked the fir tree. “They’re no bigger than I am, and one of them was even a lot smaller. Why were they left with all their branches on? Where are they going to?”

“We’ll tell you where! We’ll tell you where!” chirruped the sparrows. “We’ve been in the town, looking in through the windows! We know where they go to! Why, they go to the greatest honor and glory you can think of! We’ve peeped in through the windows and seen them planted in the middle of the warm room and decorated with the loveliest of things, such as golden apples, gingerbread, toys, and hundreds and hundreds of candles!”

“And then. . . ?” asked the fir tree, trembling in all its branches. “And then? What happens then?”

“Why, that’s all we saw! It was marvelous!”

“I wonder if I was born for this glorious life?” thought the tree joyfully. “It’s even better than crossing the sea! I’m just dying for it! I do wish it was Christmas! I’m pining! I can’t think what’s come over me!”

“Be glad of me!” said the air and the sunshine. “Be glad of your healthy youth, here in the open!”

But it wasn’t a bit glad, though it grew and grew. Winter and summer, it was always green, dark green; and people who saw it said: “That’s a nice tree!” And at Christmas it was the first of all to be felled. The axe cut deep into its marrow and it fell with a sigh to the ground, feeling a pain and faintness. It was so sad at the thought of parting from home, from the spot where it had grown up, knowing that it would never more see its dear old companions, the little bushes and the flowers that grew round it, nor even, perhaps, the birds. Going away wasn’t a bit pleasant. It came to itself in the yard when, unloaded along with the other trees, it heard a man say: “That’s a beauty! We’ll have that one!”

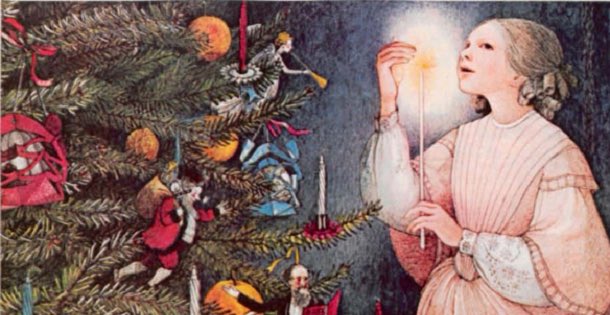

Now two servants in full dress came and took the tree into a lovely big room. There were portraits hanging on the walls, and standing by the large tiled fireplace were big Chinese vases with lions on the lids. There were rocking chairs, silk sofas, and big tables piled with picture books and toys worth a hundred times a hundred shillings — or so the children said. The fir tree was stood up in a big barrel filled with sand, though nobody could see it was a barrel, as green cloth was hung round it and it stood on a big gaily colored carpet. How the tree trembled! Whatever was going to happen? Servants and young ladies both began to decorate it. On the branches they hung little bags cut out of colored paper, each one filled with sweets. Golden apples and walnuts hung as though they had grown there, and over a hundred red, blue, and white candles were fixed on to the branches. Dolls that were the living image of people (and that the tree had never seen the like of) hung among the greenery, and right at the very top was a big star made of gold tinsel. It was gorgeous, positively gorgeous!

“Tonight,” they all said, “tonight it’s going to be all lit up!”

“Oh,” thought the tree, “if only it was tonight! If only the lights would soon go on! And I wonder what will happen then? Will trees come from the wood to look at me, I wonder? Will the sparrows fly about the window, I wonder? Shall I grow fast here and stand decorated winter and summer, I wonder?”

Oh yes, it had the right ideas. But the sheer longing had given it a proper bark ache; and bark ache is as bad for a tree as headache is for us.

At last the candles were lit. What splendor, what magic! The glory of it made the tree tremble in every limb: so much that one of the candles set fire to the greenery; it hurt horribly.

“Goodness gracious!” cried the young ladies, hastening to put it out.

The tree was too frightened even to tremble now. It was really horrid! It was so afraid of losing some of its finery, and was quite bewildered by all the glory. And then all at once the folding doors were opened and a crowd of children came rushing in, as though they would upset the whole tree; the older people quietly followed them. The little ones stood perfectly still, but only for a moment; for then they all shouted for joy, making the whole place ring with their cries. They danced round the tree, while presents were picked off one after another.

“What are they up to?” thought the tree. “What’s going to happen?” The candles burnt right down to the branches, and as they did so they were blown out and afterwards the children were allowed to strip the tree. And the way they rushed at it, making it creak in all its branches! If it hadn’t been fastened to the ceiling by its tip and its golden star it would have crashed.

The children were skipping around with their splendid toys, nobody looking at the tree except the old nurse, who went peering in among the branches, though only to see whether a fig or an apple had been forgotten.

“A story! A story!” cried the children, pulling a fat little man over toward the tree. And sitting down underneath it, he said: “Now we’re in the wood, and it won’t do the tree any harm to listen to it. But I’m only going to tell one story. Would you like the one about Imsy Whimsy, or the one about Willy Nilly, who fell downstairs and yet came out top and married the princess?”

“Imsy Whimsy!” cried some. “Willy Nilly!” cried others. There never was such shouting and screaming! Only the fir tree held its tongue, thinking to itself: “Don’t I come in here! Don’t I have a part?” Of course it had been in it; it had played its part.

And then the man told the story of Willy Nilly, who fell downstairs and yet came out top and married the princess. And the children clapped their hands and shouted: “Go on! Go on!” wanting “Imsy Whimsy” as well, but getting only “Willy Nilly.” The fir tree stood perfectly still and full of thought: the birds in the wood had never told anything of this sort. “Willy Nilly fell downstairs and yet married the princess! Ah yes, that’s the way of the world!” thought the fir tree, believing the story to be true because such a nice man had told it. “Ah yes, who knows? Perhaps I shall fall downstairs and marry a princess!” And it looked forward to being dressed in candles and toys and in gold and fruit the next day.

“I won’t tremble tomorrow!” it thought. “I’ll really enjoy all my splendor. I shall hear the story of Willy Nilly again tomorrow, and perhaps the one about Imsy Whimsy as well.” And the tree stood silent and thoughtful all night.

In the morning the servants came in.

“Now for the finery again!” thought the tree. But they dragged it out of the room and upstairs into the attic, where, in a dark corner, without a gleam of daylight, they left it. “What’s the meaning of this?” thought the tree. “I wonder what I’m going to do here? I wonder what I’m going to be told here?” And, leaning up against the wall, it stood thinking and thinking. And it had plenty of time for it, for days and nights went by. Nobody came; and when at long last somebody did, it was only to put some big boxes away in a corner. The tree stood quite hidden; anyone would have thought it was clean forgotten.

“It’ll be winter outside!” thought the tree. “The ground will be hard and covered with snow; they won’t be able to plant me. So they’ll be leaving me here in shelter till the spring! How very thoughtful of them! How good human beings are! If only it wasn’t so dark — and so dreadfully lonely! Not even a little hare! It was really so nice in the wood when the snow lay round about and the hare bounded past; yes, even when it jumped over me, though then I didn’t like it. It’s so awfully lonely up here!”

“Squeak, squeak!” said a little mouse just then, popping out of its hole, followed by another one. They came sniffing at the fir tree and slipping in and out among its branches.

“Isn’t it horribly cold!” said the little mice. “It’s a heavenly place, though, except for that! Isn’t it, old fir tree?”

“I’m not at all old!” said the fir tree. “There are plenty a lot older than I am!”

“Where do you come from?” asked the mice. “And what do you know?” (They were so dreadfully inquisitive.) “Tell us, please, about the loveliest place on earth! Have you been there? Have you been in the larder, where there are cheeses on the shelves and hams hanging under the ceiling; where life’s a bed of tallow candles, and where you go in lean and come out fat?”

“I don’t know the place!” said the tree. “But I know the wood where the sun shines, and where the birds sing!” And it told the whole story of its youth. The mice had never heard the like of it, and they listened and they said: “Why, what a lot you’ve seen! How happy you have been!”

“Have I?” said the fir tree, thinking over the story it had been telling. “Why yes, they were rather pleasant times, when you come to think of it!” And then it went on to tell of Christmas Eve, when it had been decorated with cakes and candles.

“Oh,” said the little mice, “how happy you’ve been, old fir tree!”

“I’m not old at all!” said the tree. “I only came out of the wood this winter! I’m in my prime and have only had my growth checked!”

“What a lovely storyteller you are!” said the little mice; and the next night they brought four other little mice to listen to the tree. And the more it told, the more clearly it remembered everything; and it thought to itself: “Yes, they were rather pleasant times! But they may come again; they may come again! Willy Nilly fell downstairs and yet married the princess, and perhaps I may marry a princess.” And the fir tree’s thoughts turned to a birch tree— such a pretty little birch tree—which grew in the wood; to the fir tree this was a real, lovely princess.

“Who’s Willy Nilly?” asked the little mice. And the fir tree told them the whole fairy tale; it remembered every single word of it. And the little mice were ready to jump right to the top of the tree for very joy. The next night many more mice came, and on the Sunday even two rats. But they said that the story wasn’t amusing, and this saddened the little mice, for now they, too, thought less of it.

“Is that the only story you know?” asked the rats.

“That’s all!” answered the tree. “I heard it on the happiest evening of my life; only then I never realized how happy I was!”

“It’s an extremely bad story! Don’t you know any with bacon and tallow candles in? No pantry stories?”

“No!” said the tree.

“Then you can keep it!” said the rats, and in they went.

In the end the little mice also stayed away, and the tree sighed: “It was so nice when the nimble little mice used to sit round me, listening to my story! Now even that’s all gone! But I’ll remember to enjoy myself when I’m taken out again!”

But when would that be… ? Well now, one morning somebody came rummaging about in the attic. The boxes were moved and the tree was pulled out. It was rather rough, the way they threw it on the floor, but then all at once a man dragged it toward the stairs where the daylight shone.

“Now for a new life!” thought the tree. It could feel the fresh air and the first sunbeam — and now it was out in the yard. It was all so quick; the tree clean forgot to look at itself, there was so much to see round about. The yard was next to a garden, and everything there was in bloom. Roses hung fresh and fragrant over the little railing, the lime trees were blossoming, and the swallows were flying about saying: “Twitter-twitter-tweet, my husband’s come!” But they didn’t mean the fir tree.

“Now I shall live!” it cried joyfully, spreading wide its branches. But, alas, they were all withered and yellow; and it lay in a corner among weeds and nettles. The gold paper star was still at the top, glittering now in the brilliant sunshine.

Playing in the yard were a few of the merry children who had danced round the tree at Christmastime and had been so delighted with it. One of the smallest rushed up and tore off the gold star.

“Look what’s still on the ugly old Christmas tree!” he said, trampling on its branches and crunching them under his boots.

And the tree looked at all the glorious flowers and fresh growth in the garden, and it looked at itself; and it wished that it had stayed in its dark corner of the attic. It thought of the freshness of youth in the wood, of the merry Christmas Eve, and of the little mice that had listened so delighted to the story of Willy Nilly.

“All, all over!” said the poor little tree. “If only I’d been happy when I could have been! All, all over!”

And the servant came and chopped the tree into little bits; a whole bundle of them. It made a lovely blaze under the scullery copper; and it sighed so deeply, every sigh like a little crackle. So the children playing in the yard ran inside and sat down in front of the fire, looking into it and crying “Bing, bang!”

The boys played in the yard, the smallest wearing on his breast the gold star which the tree had borne on its happiest evening. Now that was all over, and it was all over with the tree, and the story’s over as well! All, all over! And that’s the way of every story!

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now