Conflicts of Interest: The Post’s Solution

Conflict of interest has been a frequent topic in the news, as people debate the ethics of President Donald Trump’s foreign and domestic business dealings.

The principle of “conflict of interest” is clear: It’s the difference between personal interests and official responsibilities. Conflict-of-interest laws have been established, as Justice Antonin Scalia put it, to ensure each lawmaker will use his influence and his vote “as trustee for his constituents, not as a prerogative of personal power.”

What is less clear, though, is how to know when a politician has chosen personal gain over public good. How can you judge a senator’s personal intentions when he or she votes?

The problem of divided loyalties reaches back to the early years of our republic. Thomas Jefferson knew the money of special interests would tempt lawmakers. When he presided over the Senate in 1801, he established a rule that said, “Where the private interests of a member are concerned in a bill or question, he is to withdraw.”

Whenever a congressman did not recuse himself from matters touching on his personal interests, the law continued, his arguments and his vote should be tossed out.

It would be hard to say how faithfully Congress followed Jefferson’s law. But we know that, just seven years after Jefferson’s death, Senator Daniel Webster was selling his services to the Bank of the United States. Webster was on the committee that was considering the bank’s charter at a time when President Andrew Jackson wanted to shut it down. Webster strongly supported the bank, but not for free, it appears. In 1833, Webster wrote the bank president, “I believe my retainer has not been renewed or refreshed as usual. If it be wished that my relation to the bank should be continued, it may be well to send me the usual retainers.”

By 1874, the House of Representatives had fallen even further from Jefferson’s strict adherence. In that year, it passed a law that allowed congressmen to vote in their private interests so long as the measure benefitted others — presumably their constituents. The law was promoted by Speaker of the House James Blaine. At the time, Blaine was offering his services to the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad in exchange for stock.

By 1962, corruption scandals prompted Congress to pass Title 18, Second 208 of the U.S. Code. This law barred legislators from participating in matters in which they, their families, their business partners, or their associations could financially benefit.

When the legislators wrote the law, they made it apply to all public officials in the federal government except the president and vice president.

The law hasn’t resolved all the questions about conflicted interests. Enforcing the law requires investigators to prove that a legislator intended to benefit himself, and it’s hard to prove intentions.

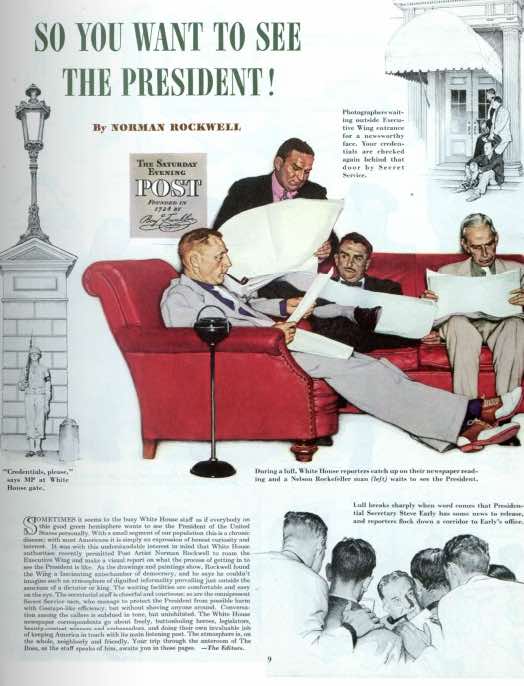

While the Post editors welcomed the 1962 law, they expected further problems with congressional corruption. So they offered a simple solution, one which would resolve questions of who benefited from what: disclosing personal finances.

Disclosure: An Antidote for Conflict of Interests

Last fall Post editors Ben Bagdikian and Don Oberdorfer explored in depth the problem of conflict of interests in the Congress of the United States. They reported that while the Congress forbade government officials and judges to hold private financial stakes which might conflict with their public duties, there was nothing to prevent members of the legislative body from doing that very same thing themselves. Bagdikian and Oberdorfer concluded that “one possible solution to the problem of hidden interests is for every member of Congress, or every candidate for Congress, to reveal his finances to his fellows and the public.”

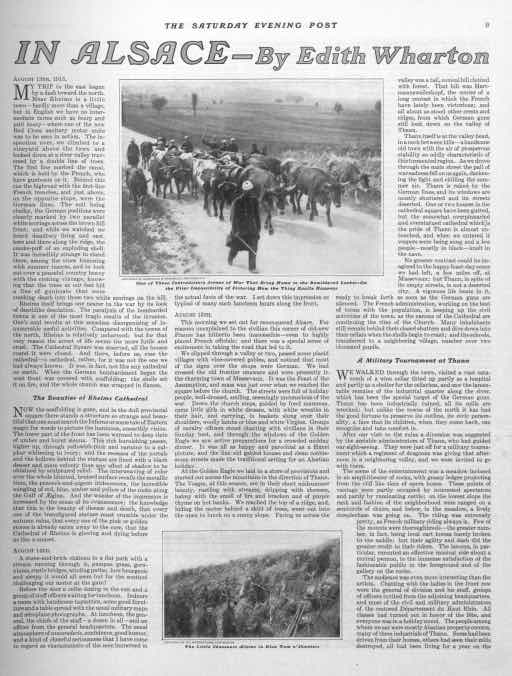

Several members of Congress had already taken this step. Sen. Joseph Clark revealed his wealth last fall, and his fellow Pennsylvanian, Sen. Hugh Scott, followed suit. Sen. Stephen Young of Ohio sold his stock in two sugar companies and an airline when committee assignments gave him special powers in these fields. He also disclosed his stock holdings.

Recently Sen. Jacob Javits of New York revealed his stock holdings on the floor of the Senate. His colleague, Sen. Kenneth Keating, announced his intention to publish a list of his securities holdings and introduced a bill to require such disclosure by members of the House and Senate. Congresswoman Edith Green of Oregon has proposed establishment of a 15-member commission on legislative ethics to study the conflict-of-interests question. She has introduced bills that would require, among other things, a full disclosure by congressmen of their financial interests.

Congress should pass such legislation. It would accomplish two important objectives: First, it would eliminate the double standard that now prevails by putting Congress on the same ethical footing with the executive branch of the Government; second, disclosure would be the most effective means of preventing members of Congress from taking advantage of the public trust that their public offices imply.

Editorial, April 6, 1963

Unfortunately, disclosing finances doesn’t end all questions of conflicts of interest. Last September, Donald Trump filed a 104-page financial disclosure, but he didn’t share his tax returns. For critics, many concerns remain.

Featured image: Shutterstock

“The Inhabitants of Venus” by Irwin Shaw

Originally published on January 26, 1963

He had been skiing since early morning, and he was ready to stop and have lunch in the village, but Mac said, “Let’s do one more before eating,” and, since it was Mac’s last day, Robert agreed to go up again. The weather was spotty, but there were a few clear patches of sky, and the visibility had been good enough for decent skiing most of the morning. The téléférique was crowded, and they had to push their way in among the bright sweaters and anoraks and the bulky packs of the people carrying picnic lunches and extra clothing and skins for climbing. The doors closed and the cabin swung out of the station, over the belt of pine trees at the base of the mountain.

The passengers were packed in so tightly that it was hard to reach for a handkerchief or light a cigarette. Robert was pressed, not unpleasurably, against a handsome young Italian woman with a dissatisfied face, who was explaining to someone over Robert’s shoulder why Milan was such a miserable city in the wintertime. “Milano si trova in un bacino deprimente,” the woman said, “bagnato dalla pioggia durante tre mesi all’anno. E, nonostante it loro gusto per l’opera, i Milanesi non sono altro cite volgari materialisti the solo it denaro interessa.” Robert knew enough Italian to understand that she was saying that Milan was in a dismal basin which was swamped by rain for three months a year and that the Milanese, despite their taste for opera, were crass and materialistic and interested only in money.

Robert smiled. Although he had not been born in the United States, he had been a citizen since 1944, and it was pleasant, in the heart of Europe, to hear somebody else besides Americans being accused of materialism and a singular interest in money.

“What’s the Contessa saying?” Mac whispered above the curly red hair of a small woman who was standing between him and Robert. Mac was a lieutenant on leave from his outfit in Germany. He had been in Europe nearly three years and, to show that he was not just an ordinary tourist, he called all pretty Italian girls Contessa. Robert had met him a week before in the bar of the hotel where they were both staying. They were the same kind of skiers, adventurous and looking for difficulties; they had skied together every day, and they were already planning to come back at the same time for the next winter’s holiday, if Robert could get over again from America.

“The Contessa is saying that in Milan all they’re interested in is money,” Robert said, keeping his voice low, although in the babble of conversation in the cabin there was little chance of being overheard.

“If I was in Milan,” Mac said, “and she was in Milan, I’d be interested in something besides money.” He looked with open admiration at the Italian girl. “Can you find out what run she’s going to do?”

“What for?” Robert asked.

“Because that’s the run I’m going to do,” Mac said, grinning. “I plan to follow her like her shadow.”

“Mac,” Robert said, “don’t waste your time. It’s your last day.”

“That’s when the best things always happen,” Mac said. “The last day.” He beamed — huge, overt, uncomplicated — at the Italian girl, who took no notice of him. She was busy now complaining to her friend about the natives of Sicily.

The sun came out for a few minutes, and the cabin grew hot, with 40 people jammed into such a small space, and Robert half-dozed, not bothering to listen to the voices speaking French, Italian, English, Schweizerdeutsch and German, on all sides of him. Robert liked being in the middle of this informal congress of tongues. It was one of the reasons he came to Switzerland to ski whenever he could take time off from his job. In the angry days through which the world was passing, there was a ray of hope in this good-natured, polyglot chorus of people who smiled at strangers, who had collected in these shining white hills merely to enjoy the innocent pleasures of sun and snow.

The feeling of generalized cordiality that Robert experienced on these trips was intensified by the fact that most of the people on the lifts and runs seemed more or less familiar to him. Skiers formed a kind of loose, international club, and the same faces kept turning up year after year in Mégève, Davos, St. Anton, Val d’Isére, so that after a while you had the impression you knew almost everybody. There were four or five Americans in the cabin whom Robert was sure he had seen at Stowe at Christmas. The Americans had come over in one of the chartered ski-club planes that Swissair ran every winter on a cut-rate basis. They were young and enthusiastic, and none of them had ever been to Europe before, and they were noisily appreciative of everything — the Alps, the food, the snow, the weather, the peasants in their blue smocks, the chic of the lady skiers and the skill and good looks of the instructors. They were popular with the villagers because they were so obviously enjoying themselves. Besides, they tipped generously, in the American style, with what was, to Swiss eyes, an endearing disregard of the fact that a service charge of 15 percent had been added automatically to every bill before it was presented to them. Two of the girls were very attractive, in a youthful prettiest-girl-at-the-prom way, and one of the young men, a lanky boy from Philadelphia, the informal leader of the group, was a beautiful skier who guided the others down the runs and helped the dubs.

The Philadelphian, who was standing near Robert, spoke to him as the cabin swung high over a steep, snowy face of the mountain. “You’ve skied here before, haven’t you?” he said.

“Yes,” Robert said, “a few times.”

“What’s the best run down this time of day?” the Philadelphian asked. He had the drawling, flat tone of the good New England schools that Europeans use in their imitations when they wish to make fun of upper-class Americans.

“They’re all OK today,” Robert said.

“What’s this run everybody says is so good?” the boy asked. “The — the Kaiser something-or-other?”

“The Kaisergarten,” Robert said. “It’s the first gully to the right after you get out of the station on top.”

“Is it tough?” the boy asked.

“It’s not for beginners,” Robert said.

“You’ve seen this bunch ski, haven’t you?” The boy waved vaguely to indicate his friends. “Do you think they can make it?”

“Well,” Robert said doubtfully, “there’s a narrow, steep ravine full of bumps halfway down, and there are one or two places where it’s advisable not to fall, because you’re liable to keep on sliding all the way if you do.”

“We’ll take a chance,” the Philadelphian said. “It’ll be good for their characters. Boys and girls,” he said, raising his voice, “the cowards will stay on top and have lunch. The heroes will come with me. We’re going to do the Kaisergarten.”

“Francis,” one of the pretty girls said, “I do believe it is your sworn intention to kill me on this trip.”

“It’s not as bad as all that,” Robert said, smiling at the girl.

“Say,” the girl said, looking with interest at Robert, “haven’t I seen you someplace before?”

“On this lift, yesterday,” Robert said.

“No.” The girl shook her head. She had on a black, fuzzy, lambskin hat, and she looked like a high-school drum majorette pretending to be Anna Karenina. “Before yesterday. Someplace.”

“I saw you at Stowe,” Robert confessed. “At Christmas.”

“Oh, that’s where,” she said. “I saw you ski. Oh, my, you’re silky.”

Mac broke into a loud laugh at this description of Robert’s skiing style.

“Don’t mind my friend,” Robert said, enjoying the girl’s admiration. “He’s a coarse soldier who is trying to beat the mountain to its knees by brute strength.”

“Say,” the girl said, looking puzzled, “you have a funny little way of talking. Are you American?”

“Well, yes,” Robert said. “I am now. I was born in France.”

“Oh, that explains it,” the girl said. “You were born among the crags.”

“I was born in Paris,” Robert said.

“Do you live there now?”

“I live in New York,” Robert said.

“Are you married?” the girl asked anxiously.

“Barbara,” the Philadelphian said, “behave yourself.”

“I just asked the man a simple, friendly question,” the girl protested. “Do you mind, Monsieur?”

“Not at all.”

“Are you married?”

“Yes,” Robert said.

“He has three children,” Mac added helpfully. “The oldest one is going to run for President in the next election.”

“Oh, isn’t that too bad?” the girl said. “I set myself a goal on this trip. I was going to meet one unmarried Frenchman.”

“I’m sure you’ll manage it,” Robert said.

“Three children,” the girl said. “My! How old are you, anyway?”

“Thirty-nine,” Robert said.

“Where is your wife now?” the girl said.

“In New York.”

“Pregnant,” Mac said, more helpful than ever.

“And she lets you run off and ski all alone like this?” the girl asked incredulously.

“Yes,” Robert said. “Actually I’m in Europe on business, and I’m sneaking off for 10 days.”

“What business?” the girl asked.

“I’m a diamond merchant,” Robert said. “I buy and sell diamonds.”

“That’s the sort of man I’d like to meet,” the girl said. “Somebody awash with diamonds. But unmarried.”

“Barbara!” the Philadelphian said.

“I deal mostly in industrial diamonds,” Robert said. “It’s not exactly the same thing.”

“Even so,” the girl said.

“Barbara,”. the Philadelphian said, “pretend you’re a lady.”

“If you can’t speak candidly to a fellow American,” the girl said, “who can you speak candidly to?” She looked out the plexiglass window of the cabin. “Oh, dear,” she said, “it’s a perfect monster of a mountain, isn’t it? I’m in a fever of terror.” She turned and regarded Robert again. “You do look like a Frenchman,” she said. “Terribly polished. You’re definitely sure you’re married?”

“Barbara,” the Philadelphian said forlornly.

Robert laughed, and Mac and the other Americans laughed, and the girl smiled under her fuzzy hat, amused by her own clowning and pleased at the reaction she was getting. The other people in the car, who could not understand English, smiled good-naturedly, happy, even though they were not in on the joke, to be the witnesses of this youthful gaiety.

Then through the laughter Robert heard a man’s voice say, in tones of quiet, cold distaste, “Schaut euch diese dummen amerikanischen Gesichter an! Und diese Leute bilden sich ein, sie waren berufen, die Welt zu regieren.”

Robert had learned German as a child from his Alsatian grandparents, and he understood what he had just heard, but he forced himself not to turn to see who had spoken. His years of temper, he liked to believe, were behind him, and, if nobody else in the cabin had overheard or understood the words, he was not going to be the one to force the issue. He was here to enjoy himself, and he didn’t feel like getting into a fight or dragging Mac and the other kids into one. Long ago he had learned the wisdom of playing deaf when he heard things like that, and worse. If some bastard of a German wanted to say, “Look at those stupid American faces. And these are the people who think they have been chosen to rule the world,” it made very little real difference to anybody, and a grown man ignored it if he could. So he didn’t look to see who had said it, because he knew that if he picked out the man he wouldn’t be able to let it go. This way — as long as the hateful voice was anonymous — he could let it slide, along with many other things that Germans had said during his lifetime.

The effort of not looking was difficult, though, and he closed his eyes, angry with himself for being so disturbed by a scrap of overheard malice. It had been a perfect holiday up to now, and it would be foolish to let it be shadowed, even briefly, by a random voice in a crowd. If you came to Switzerland to ski, Robert told himself, you had to expect to find some Germans. But each year now there were more and more of them, massive, prosperous-looking men and sulky-looking women with the suspicious eyes of people who believe they are in danger of being cheated. Men and women both pushed more than was necessary in the lift lines, with a kind of impersonal egotism, an unquestioning assumption of precedence. When they skied they did it grimly, in large groups, as if under military orders. At night, when they relaxed in the bars and Stüblis, their merriment was more difficult to tolerate than their dedicated daytime gloom and Junker arrogance. They sat in red-faced platoons, drinking gallons of beer, volleying great bursts of heavy laughter and roaring glee-club arrangements of student drinking songs. Robert had never heard them sing the Horst Wessel song, but he had noticed that long ago they had stopped pretending they were Swiss or Austrian, or that they had been born in Alsace. Somehow to the sport of skiing, which is, above all, individual and light and an exercise in grace, the Germans seemed to bring the image of the herd. Once or twice when he had been trampled in the téléférique station he had let some of his distaste show to Mac, but Mac, who was far from being a fool under his puppy-fullback exterior, had said, “The trick is to isolate them, lad. It’s only when they’re in groups that they get on your nerves. I’ve been in Germany for three years, and I’ve met a lot of good fellows and some smashing girls.”

Robert had agreed that Mac was probably right. Deep in his heart he wanted to believe that Mac was right. Before and during the war the problem of the Germans had occupied so much of his waking life that VE Day had seemed a personal liberation from them, a kind of graduation ceremony from a school in which he had been forced to spend long years trying to solve a single boring, painful problem. He had reasoned himself into believing that defeat had returned the Germans to rationality. So, along with the relief he felt because he no longer ran the risk of being killed by them, there was an almost-as-intense relief that he no longer had to think about them.

After the war he had believed in establishing normal relations with the Germans as quickly as possible, both as good politics and as simple humanity. He drank German beer and even bought a Volkswagen, although he would not have favored equipping the German army with the hydrogen bomb. In the course of his business he had few dealings with Germans, and it was only here, in this village in the Graubünden where their presence was becoming so much more apparent each year, that the idea of Germans disturbed him anymore. But he loved the village, and the thought of abandoning his yearly vacation because of the prevalence of license plates from Munich and Düsseldorf was repugnant to him. Maybe, he thought, from now on he would come at a different time, in January instead of late February. Late February through early March, when the sun was warmer and shone until six o’clock in the evening, was the German season. The Germans were sun gluttons, and they could be seen all over the hills, stripped to the waist, sitting on rocks, eating their picnic lunches, greedily absorbing each precious ray of sunlight. It was as though they came from a country perpetually covered by mist, like the planet Venus, and had to soak up as much brightness and life as possible during their short holidays in order to endure the harsh gloom of their homeland and the conduct of the other inhabitants of Venus for the rest of the year.

Robert smiled to himself at this tolerant concept and felt better disposed toward everyone around him. Maybe, he thought, if I were a single man I’d find a Bavarian girl and fall in love with her and finish the whole thing off.

“I warn you, Francis,” the girl in the lambskin hat was saying, “if you do me to death on this mountain there are three juniors at Yale who will track you down to the ends of the earth.”

Then he heard the German voice again. “Warum haben die Amerikaner nicht genügend Verstand,” the voice said, low but distinctly, near him, the accent clearly Hochdeutsch, not Zurichois or any of the other variations of Schweizerdeutsch, “ihre dummen kleinen Nutten zu Hause zu lassen, wo sie hingehören?”

Now he knew there was no avoiding looking and there was no avoiding doing something about it. He glanced at Mac first, to see if Mac, who understood a little German, had heard. Mac was huge and could be dangerous; and, for all his easy good nature, if he had heard the man say, “Why don’t the Americans have the sense to leave their silly little tramps at home where they belong?” the man would have been in for a beating. But Mac was still beaming placidly at the Contessa. That was all to the good, Robert thought. The Swiss police took a dim view of fighting, no matter what the provocation, and Mac, enraged, would wreak terrible damage in a fight and would more than likely wind up in jail. For an American career soldier stationed in Frankfurt a brawl like that could have serious consequences. The worst that can happen to me, Robert thought as he turned to find the man who had spoken, is a few hours in the pokey and a lecture from the magistrate about abusing Swiss hospitality.

Almost automatically Robert decided that when they got to the top he would follow the man out of the car, tell him quietly that he, Robert, had understood what had been said about Americans, and swing immediately. I just hope, Robert thought, that whoever it is isn’t too damned big.

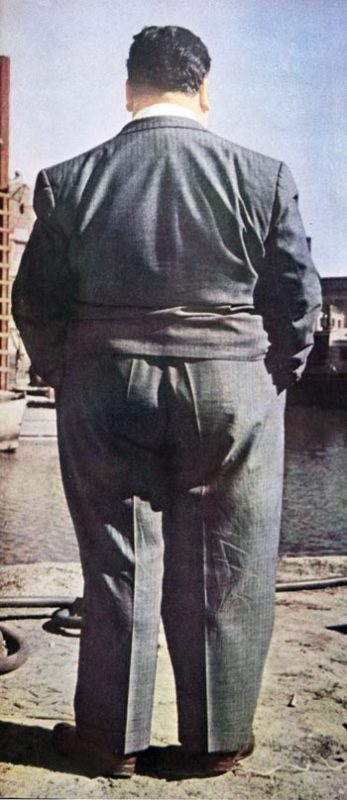

For a moment Robert couldn’t pick out his opponent-to-be. There was a tall man with his back to Robert, on the other side of the Italian woman, and the voice had come from that direction. Because of the crowd Robert could see only his head and shoulders, which looked bulky and powerful under a black parka. The man had on the kind of black cap that had been worn by the Afrika Korps during the war. Beneath the cap the blond hair, which was thick and very low on the back of his neck, was plentifully streaked with gray. The man was with a plump, hard-faced woman who was whispering earnestly to him but not loudly enough for Robert to hear what she was saying. Then the man said crisply in German, replying to her, “I don’t care how many of them understand the language. Let them understand,” and Robert knew that he had found his man.

A tingle of anticipation ran through him, making his hands and arms feel tense and jumpy. He regretted that the cabin wouldn’t arrive at the top for another five minutes. Now that he had decided the fight was inevitable he could hardly bear waiting. He stared fixedly at the man’s broad, black-nylon back, wishing the fellow would turn and show his face. Judging by the man’s height and the width of his shoulders he was at least 20 pounds heavier than Robert, but Robert was wiry and in good condition, and in the days when he still got into fights he had been a stubborn performer with a punch surprisingly damaging for someone his size. He wondered if the man would go down with the first blow, if he would apologize, if he would try to use his ski poles. Robert decided to keep his own poles handy, just in case, although Mac could be depended upon to police matters thoroughly if he saw weapons being used. Deliberately Robert took off his heavy leather mittens and stuck them in his belt. Bare knuckles would be more effective. He wondered fleetingly if the man was wearing a ring. He kept his eyes fixed on the back of the man’s neck, willing him to turn. Then the plump woman noticed his stare. She dropped her eyes and whispered something to the man in the black parka, and after several seconds he turned, pretending that it was a casual, unmotivated movement. The man looked squarely at Robert, and Robert thought, If you ski long enough you meet every other skier you’ve ever known. At the same moment he knew that it wasn’t going to be a nice, simple little fistfight on top of the mountain. For the first time in his life he wanted to kill a man, and the man he wanted to kill was the one whose icy blue eyes, fringed with pale, blond lashes, were staring challengingly at him from under the black peak of the Afrika Korps cap.

It was a long time ago, the winter of 1938, in the French part of Switzerland, and he was 14 years old. The sun was setting behind another mountain, and it was 10 below zero, and he was lying in the snow with his foot turned in that funny, unnatural way, although the pain hadn’t really begun yet, and the eyes were looking down at him.

He had done something foolish, and at the moment he was more worried about what his parents would say when they found out than about the broken leg. He had gone up alone, late in the afternoon when almost everybody else was off the mountain. And even so he hadn’t stayed on the packed snow of the regular runs, but had started bushwhacking through the forest, searching for powder snow that hadn’t been tracked by other skiers. One ski had caught on a hidden root, and he had fallen, hearing the sickening, dry cracking sound from his right leg even as he pitched forward.

Trying not to panic, he had sat up, facing in the direction of the normal track, seeing the markers 100 meters away through the pine forest. If any skiers happened to come by they might just, with luck, be able to hear him if he shouted. He did not try to crawl toward the line of poles, because when he moved a queer feeling flickered from his ankle up his leg into his stomach, making him want to throw up.

The shadows were very long in the forest, and only the highest peaks were rose-colored now against a frozen green sky. He was beginning to feel the cold, and from time to time he was shaken by spasms of shivering.

I’m going to die here, he thought. I’m going to die here tonight. He thought of his parents and his sister comfortably seated this moment, probably having tea, in the warm dining room of the chalet two miles down the mountain, and he bit his lips to keep back the tears. They wouldn’t start to worry about him for another hour or two yet, and then when they did, and started to do something about finding him, they wouldn’t know where to begin. He had known none of the seven or eight people on the lift with him on his last ride up, and he hadn’t told anyone what run he was going to take. There were three different mountains, with separate lifts and numberless variations of runs that he might have taken, and finding him in the dark would be an almost hopeless task. He looked up at the sky. There were clouds moving in from the east, a high black wall covering the already darkened sky. If it snowed that night there was a good chance they wouldn’t even find his body before spring. He had promised his mother that no matter what happened, he would never ski alone, and now he had broken the promise, and this was his punishment.

Then he heard the sound of skis coming fast, a harsh, metallic sound on the iced snow of the run. Before he could see the skier he began to shout with all the strength of his lungs, frantically, “Au secours! Au secours!”

A dark shape appeared high above him for a second, disappeared behind a clump of trees, then shot into view much lower down, almost on a level with the place where he was sitting. Robert shouted wildly, not uttering words anymore, just a senseless, passionate, throat-bursting claim on the attention of the human race, represented, for this one instant at sunset on this cold mountain, by the dark, expert figure plunging, with a scraping of steel edges and a whoosh of wind, toward the village below.

Then, miraculously, in a swirl of snow, the figure stopped. Robert shouted. The sound of his voice echoed hysterically in the forest. For a moment the skier didn’t move, and Robert shook with the fear that it was all a hallucination, a mirage of sight and sound, that there was no one there on the beaten snow at the edge of the forest, that he was only imagining his own shouts, that despite all the fierce effort of his throat and lungs he was mute, unheard.

Suddenly he couldn’t see anything. He had the sensation of something sinking somewhere within him, of a rush of warm liquid inundating all the ducts and canals of his body. He waved his hands weakly and sank slowly over in a faint.

When he came to, a man was kneeling over him, rubbing his cheeks with snow. “You heard me,” Robert said in French. “I was afraid you wouldn’t hear me.”

“Ich verstehe nicht,” the man said. “Nicht parler Französisch.”

“I was afraid you wouldn’t hear me,” Robert repeated, in German.

“You are a stupid little boy,” the man said severely, in clipped, educated German. “And very lucky. I am the last man on the mountain.” He felt Robert’s ankle, his hands hard but deft. “Nice,” he said ironically, “very nice. You’re going to be in plaster for at least three months. Here — lie still. I am going to take your skis off. You will be more comfortable.” Working swiftly, he undid the long leather thongs and stood the skis up in the snow. Then he swept the snow off a stump a few yards away, got behind Robert and put his hands under Robert’s armpits. “Relax,” he said. “Do not try to help me.” He picked Robert up. “Luckily, you weigh nothing. How old are you — eleven?”

“Fourteen,” Robert said.

“What’s the matter?” the man said, laughing. “Don’t they feed you in Switzerland?”

“I’m French,” Robert said.

“Oh.” The man’s voice went flat. “French.” He half-carried, half-dragged Robert over to the stump and sat him down gently on it. “There,” he said, “at least you’re out of the snow. You won’t freeze — for the time being. Now, listen carefully. I will take your skis down with me to the ski school, and I will tell them where you are and tell them to send a sled for you. They should get to you in less than an hour. Now whom are you staying with in town?”

“My mother and father. At the Chalet Montana.”

“Good.” The man nodded. “The Chalet Montana. Do they speak German too?”

“Yes.”

“Excellent,” the man said. “I will telephone them and tell them that their foolish son has broken his leg and that the patrol is taking him to the hospital. What is your name?”

“Robert.”

“Robert what?”

“Robert Rosenthal,” Robert said. “Please don’t say I’m hurt too badly. They’ll be worried enough as it is.”

The man didn’t answer immediately. He busied himself tying Robert’s skis together and slung them over his shoulder. “Do not worry, Robert Rosenthal,” he said. “I will not worry them more than is necessary.” Abruptly he started off, sweeping easily through the trees, his poles held in one hand, balancing Robert’s skis across his shoulders with the other hand.

His sudden departure took Robert by surprise, and it was only when the man was a considerable distance away, almost lost among the trees, that he realized he hadn’t thanked the man for saving his life. “Thank you,” he shouted into the growing darkness. “Thank you very much.”

The man didn’t stop, and Robert never knew whether his cry had been heard or not. Because after an hour, when it was completely dark, with the stars covered by the clouds that had been moving in from the east, the patrol had not yet appeared. Robert had a watch with a radium dial. Timing himself, he waited exactly one hour and a half, until 10 minutes past seven, and then decided that nobody was coming for him and that if he hoped to live through the night he would have to crawl out of the forest somehow and make his way down to the town by himself.

He was rigid with cold by now, and suffering from shock. His teeth chattered in a frightening way, as though his jaws were part of an insane machine over which he had no control. There was no feeling in his fingers anymore, and the pain in his leg came in ever-enlarging waves. He had put up the hood of his parka and let his head sink as low on his chest as he could, and the cloth of the parka was stiff with his frosted breath. He heard a whimpering sound somewhere around him, and it was only after what seemed like several minutes that he realized the whimpering sound was coming from him, and that there was nothing he could do to stop it.

Stiffly, with exaggerated care, he tried to lift himself off the tree stump without putting any weight on his injured leg, but at the last moment he slipped and twisted the leg as he went down into the snow. He screamed twice and lay with his face in the snow and thought of just staying that way and forgetting the whole thing, the whole intolerable effort of remaining alive. Later on, when he was much older, he came to the conclusion that the one thing that had kept him moving was the thought of his mother and father waiting for him, with an anxiety that would soon become terror, in the town below.

He pulled himself along on his belly, digging at the snow with his hands, using rocks, low-hanging branches and snow-covered roots to help him, meter by meter, out of the forest. His watch was torn off somewhere along the way, and when he finally reached the line of poles that marked the packed snow and ice of the run he had no notion of whether it had taken him five minutes or five hours to cover the 100 meters from the place where he had fallen. He lay panting, sobbing, staring at the lights of the town far below, knowing that he could never reach them, knowing that he had to reach them. The effort of crawling through the deep snow had warmed him, though, and his face was streaming with sweat, and the blood coming back into his numbed hands and feet jabbed him with a thousand needles of pain.

The lights of the town guided him now, and here and there he could see the marker poles outlined against the small, cozy, Christmasy glow of the lights. It was easier going, too, on the packed snow of the run. From time to time he managed to slide 10 or 15 meters without stopping, tobogganing on his stomach, screaming occasionally when his broken leg banged loosely against an icy bump, or twisted as he went over a steep embankment to crash down on a level place below. Once he couldn’t stop himself and fell into a swiftly rushing small stream and pulled himself out of it five minutes later with his gloves and midsection and knees soaked with icy water. And still the lights of the town seemed as far away as ever.

Finally, after he had stopped twice to vomit, he felt he couldn’t move anymore. He tried to sit up, so that if the snow came that night there would be a chance somebody might see the top of his head sticking out of the new cover in the morning. He was struggling to push himself erect when a shadow passed between him and the lights of the town. The shadow was very close and with his last breath he called out. Later on, the peasant who had rescued him said that what he had called out was “Excuse me.”

The peasant had been moving hay on a big sled from one of the hill barns down to the valley, and he rolled the hay off the sled and put Robert on instead. Then, braking carefully and taking the sled on a path that cut back and forth across the run, he brought Robert down to the valley and the hospital.

By the time his mother and father had been notified and reached the hospital, the doctor had given him a shot of morphine and was already setting the leg. So it wasn’t until the next morning, as he lay in the gray hospital room, sweating with pain, his leg in traction, that he could get out any kind of coherent story for his parents about what had happened.

“Then I saw this man skiing very fast, all alone,” Robert said, trying to speak without showing how much the effort was costing him, trying to take the look of shock and agony from his parents’ set faces by pretending that his leg hardly hurt at all, and that the whole incident was of small importance. “He heard me and came over and took off my skis and made me comfortable on a tree stump, and he asked me what my name was and where my parents were staying, and he said he’d go to the ski school and tell them where I was and to send a sled for me, and that he’d call you at the chalet and tell you they were bringing me down to the hospital. Then after more than an hour — it was pitch dark already — nobody came, and I decided I’d better not wait anymore and I started down and I was lucky and I saw this farmer with a sled and — ”

“You were very lucky,” Robert’s mother said flatly. She was a small, neat, plump woman with bad nerves, who was at home only in cities. She detested the cold, detested the mountains, detested the idea of her loved ones running what seemed to her the senseless risk of injury that skiing involved, and she came on these holidays only because Robert and his father and sister were so passionate about the sport. Now she was white with fatigue and worry, and if Robert had not been immobilized in traction she would have had him out of the accursed mountains that morning on the train to Paris.

“Now, Robert,” his father said, “is it possible that when you hurt yourself the pain did things to you and that you just imagined you saw a man and just imagined he told you he was going to call us and get you a sled from the ski school?”

“I didn’t imagine it, Papa,” Robert said. The morphine had made him feel hazy and heavy-brained, and he was puzzled that his father was talking to him that way. “Why do you think I might have imagined it?”

“Because,” his father said, “nobody called us last night until ten o’clock, when the doctor telephoned from the hospital. And nobody called the ski school either.”

“I didn’t imagine him,” Robert repeated. He was hurt that his father seemed to think he was lying. “If he came into this room I’d know him right off. He was wearing a white cap, he was a big man with a black anorak, and he had blue eyes. They looked a little funny because his eyelashes were almost white, and from a little way off it looked as though he didn’t have any eyelashes at all.”

“How old was he, do you think?” Robert’s father asked. “As old as I am?” Robert’s father was nearly 50.

“No,” Robert said. “I don’t think so.”

“Was he as old as your Uncle Jules?” Robert’s father asked.

“Yes,” Robert said. “Just about.” He wished his parents would leave him alone. He was all right now. His leg was in plaster, and he wasn’t dead, and in three months, the doctor said, he’d be walking again, and he wanted to forget everything that had happened last night in the forest.

“So,” Robert’s mother said, “he was a man of about 25, with a white cap and blue eyes.” She picked up the phone and asked for the ski school.

Robert’s father lit a cigarette and went over to the window and looked out. It was snowing. It had been snowing since midnight, heavily, and the lifts weren’t running today because a driving wind had sprung up with the snow and up on top there was danger of avalanches.

“Did you talk to the farmer who picked me up?” Robert asked.

“Yes,” said his father. “He said you were a very brave little boy. He also said that if he hadn’t found you you couldn’t have gone on more than another fifty meters.”

“Sssh.” Robert’s mother had the connection with the ski school now. “This is Mrs. Rosenthal again. Yes, thank you, he’s doing as well as can be expected,” she said, in her precise, melodious French. “We’ve been talking to him, and there’s one aspect of his story that’s a little strange. He says a man stopped and helped him take off his skis last night after he’d broken his leg, and promised to go to the ski school and leave the skis there and ask for a sled to be sent to bring him down. We’d like to know if, in fact, the man did report the accident. It would have been somewhere around six o’clock.”

She listened for a moment, her face tense. “I see,” she said, and listened again.

“No,” she said, “we don’t know his name. My son says he was about 25 years old, with blue eyes and a white cap. Wait a minute. I’ll ask.” She turned to Robert. “Robert, what kind of skis did you have? They’re going to look and see if they’re out in the rack.”

“Attenhofer’s,” Robert said. “One meter seventy. And they have my initials in red up on the tips.”

“Attenhofer’s,” his mother repeated over the phone. “And they have his initials on them. ‘R.R.’ In red. Thank you. I’ll wait.”

Robert’s father came back from the window and doused his cigarette in an ashtray. Beneath the holiday tan his face looked weary and sick. “Robert,” he said with a rueful smile, “you must learn to be more careful. You are my only male heir, and there is very little chance that I shall produce another.”

“Yes, Papa,” Robert said. “I’ll be careful.”

His mother waved impatiently at them to be quiet and listened again at the telephone. “Thank you,” she said. “Please call me if you hear anything.” She hung up. “No,” she said to Robert’s father, “the skis aren’t there.”

“It can’t be possible,” Robert’s father said, “that a man would leave a little boy to freeze to death just to steal a pair of skis.”

“I’d like to get my hands on him,” Robert’s mother said, “just for 10 minutes. Robert, darling, think hard. Did he seem — well — did he seem normal?”

“He seemed all right,” Robert said, “I suppose.”

“Was there any other thing about him that you noticed? Think hard. Anything that would help us find him. It’s not only for us, Robert. If there’s a man in this town who would do something like that to you, it’s important that people know about him before he does something even worse to other boys.”

“Mama,” Robert said, feeling close to tears under the insistence of her questioning, “I told you just the way it was. Everything. I’m not lying, Mama.”

“What did he sound like, Robert?” his mother said. “Did he have a low voice, a high voice, did he sound like us, as though he lived in Paris, did he sound like any of your teachers, did he sound like the other people from around here, did he — ”

“Oh,” Robert said, remembering.

“What is it? What do you want to say?” his mother said sharply.

“I had to speak German to him,” Robert said. Until now, what with the pain and the morphine, it hadn’t occurred to him to mention that.

“What do you mean, you had to speak German to him?”

“I started to speak to him in French, and he didn’t understand. We spoke in German.”

His parents exchanged glances. Then his mother said gently, “Was it real German? Or was it Swiss German? You know the difference, don’t you?”

“Of course,” Robert said. One of his father’s parlor tricks was giving imitations of Swiss friends in Paris speaking first French and then Swiss German. Robert had a good ear for languages, and, aside from having heard his Alsatian grandparents speak German since he was an infant, he was studying German literature in school and knew long passages of Goethe and Schiller and Heine by heart. “It was German, all right,” he said.

There was silence in the room. His father went over to the window again and looked out at the snow falling like a soft, blurred curtain outside. “I knew,” his father said quietly, “that it couldn’t just have been for the skis.”

In the end, his father won out. His mother wanted the police to try to find the man, even though his father pointed out that there were perhaps 5,000 skiers in the town for the holidays, a good percentage of them German-speaking and blue-eyed, and that trains arrived and departed with them five times a day. Robert’s father was sure that the man had left the very night Robert broke his leg, but during the remainder of his stay in the town Mr. Rosenthal prowled the snowy streets and went in and out of bars searching for the face that would answer Robert’s description of the man on the mountain. He said it would do no good to go to the police and might do harm, because once the story got out there would be plenty of people to complain that this was just another hysterical Jewish fantasy. “There are plenty of Nazis in Switzerland, of all nationalities,” Robert’s father told his mother in the course of an argument that lasted for weeks, “and this will just give them more ammunition — they’ll be able to say, ‘See, wherever the Jews go they start trouble.’”

Robert’s mother, who was made of sterner stuff and who had relatives in Germany who smuggled out disturbing letters, wanted justice at any cost, but after a while even she saw the hopelessness of pushing the matter further. Four weeks after the accident, when Robert finally could be moved, as she sat beside her son, holding his hand, in the ambulance that would take them to Geneva and then on to Paris, she said in a dead voice, “Soon we must leave Europe. I cannot stand to live anymore on a continent where things like this are permitted to happen.”

Much later, during the war, after Mr. Rosenthal had died in occupied France and Robert and his mother and sister were in America, a friend of Robert’s, who had also done a lot of skiing in Europe, heard the story of the man in the white cap and told Robert he was almost sure he recognized the man from the description Robert gave. It was a ski instructor from Garmisch, or maybe from Oberndorf or Freudenstadt, who had a couple of rich Austrian clients with whom he toured each winter from one ski resort to another. Robert’s friend didn’t know the man’s name, and the one time Robert got to Garmisch it was with French troops in the closing days of the war, and of course nobody was skiing then.

Now the man was standing just three feet from him, on the other side of the pretty Italian woman, his face framed by the straight black rows of skis, looking coolly, with insolent amusement, but without recognition, at Robert from under his almost-albino eyelashes. He was approaching 50 now, and his face was fleshy but hard and healthy, with a thin, set mouth that indicated control and self-discipline.

Robert hated him. He hated him for the attempted murder of a 14-year-old boy in 1938; he hated him for the acts he must have condoned or collaborated in during the war; he hated him for his father’s death and his mother’s exile; he hated him for what he had said about the pretty little American girl in the lambskin hat; he hated him for the impudence of his glance and the healthy, untouched robustness of his face and neck; he hated him because the man could look directly into the eyes of someone he had tried to kill and not recognize him; he hated him because he was here, bringing the idea of death and vengeance into this silvery bubble climbing through the placid holiday air of a kindly, welcoming country.

And most of all he hated the man whose cap was black now because the man betrayed and made a sour joke of the precariously achieved peace that Robert had built with his wife, his children, his job, his comfortable, easygoing, generously forgetful Americanism since the war.

The German deprived him of his sense of normality. Living with a wife and three children in a clean, cheerful house was not normal; having your name in the telephone directory was not normal; lifting your hat to your neighbor and paying your bills was not normal; obeying the law and depending upon the protection of the police was not normal. The German sent him back through the years to an older and truer normality — murder, blood, flight, conspiracy, pillage and ruin. For a while Robert had deceived himself into believing that the nature of everyday things could change. The German in the crowded cabin had now put him to rights. Meeting the German had been an accident, but the accident had revealed what was permanent and non-accidental in his life and in the life of the people around him.

Mac was saying something to him, and the girl in the lambskin hat was singing an American song in a soft, small voice, but he didn’t hear what Mac was saying, and the words of the song made no sense. He had turned away from the German and was looking at the steep stone escarpment of the mountain, now almost obscured by a swirling cloud. He felt confused and battered, and the images that raced through his mind were shadowy, veiled, like his glimpses of the mountain through the cloud — the man in the black cap lying in the snow, in a spreading red stain, himself standing over the man with a pistol in his hand (where could he find a weapon on this peaceful mountain?), the man struggling beneath him, the feel of the crushed, gasping throat between his strangling hands, the last terrified look of recognition and understanding, the man in the black cap sliding, skis flailing, hands clutching at the icy surface, going toward the brink, screaming as he went over and whirled down toward the rocks below.

And he himself? What? The plotter of a perfect crime? The joyous murderer? The just executioner? The prisoner in the dock, explaining his justifiable crime? Condemned and waking, morning after morning for the rest of his life, in a prison cell? Or exonerated and going back, as though nothing had happened, to his neat white house and ordering his wife and children to believe that nothing had changed, that although there was blood on his hands he was still the same husband, the same thoughtful father he had always been?

Murder. Murder. Men killed every hour for much less reason. They killed in the course of burglaries in which the loot was no more than 10 or 15 dollars. They killed in bars for differences of opinion. They killed in support of abstract political ideas; they killed for love, for religion, jealousy, out of exasperation.

In other times men had killed for a slight, for a glass of wine thrown in the face. Was he civilized beyond the point of avenging slights? What had to be thrown in his face before he acted, what sneers was he prepared to endure?

Was it cowardice that made him hesitate? Was he like his father, holding back because he was worried about the opinion of neighbors who said Jews made trouble wherever they went?

Other Jews had killed without compunction, careless of all opinion. The Stern gang terrorists in Palestine, Jewish gangsters in the United States. Not all Jews were like his father.

And in Europe and Africa and Asia there was constant slaughter — Algerian revolutionaries shooting policemen on the bustling streets of Paris, a student in Japan running a sword through a political leader, Congolese sergeants bayoneting tribal opponents. After all, murder was a commonplace event. Even in the United States, every hour of every day in the year, a murder was reported to the police.

During the war he had been ready enough to kill — for an ideal, for a country, for the safety of men who wore the same uniform he did. But it was harder to think of killing for himself, to avenge a wound out of his own past. Was it modesty on his part? Did he feel that he was not important enough for so grave and irrevocable an act? Was he finally the victim of his mother’s fussing and tender love, of nannies saying “Naughty boy,” of polite schools, of rabbis dreaming about Jerusalem, of children’s books, of coaches on long-forgotten athletic fields talking about fair play, of that vague, comfort-shaped, false, all-pervading doctrine by which Americans lived, whose key word was “arbitrate”?

What was there subject to arbitration between him and the man in the black cap who had left him on the mountainside to die?

It was not even a terribly special case. In the world of hatred and agony that the Germans had created, meetings between persecutors and victims were unavoidable. There had been so many persecutors, and for all their zeal they had left so many victims alive. There were the stories, so frequent in Europe, of men who had been in concentration camps who had confronted their torturers after the war and turned them in to the authorities, and had the satisfaction of witnessing their execution. But to whom could he turn this German over — the Swiss police? For what crime, under what criminal code?

He could do what an ex-prisoner had done in Budapest three or four years after the war when he had met one of his former jailers on a bridge over the Danube and had simply picked the man up and thrown him into the water and watched him drown. The ex-prisoner had explained who he was and who the drowned man was and had been let off and treated as a hero. But Switzerland was not Hungary, the Danube was far away, the war had been finished a long time ago.

Robert moved tensely in the crowded cabin. He could feel the sweat running unpleasantly down his ribs under his heavy sweater. The presence of so many people, chattering away with nothing on their minds but lunch or how to perfect the new Austrian ski technique, disturbed him and made it difficult for him to think. And he had to think. In a few minutes they would be on top of the mountain and a decision would have to be made, a decision which would change the course of his life.

No matter what he did, he had to get rid of Mac. This was something he could only solve alone. With Mac out of the way he could follow the man and wait for events to push him to one action or another. He might even surprise the man alone somewhere on the slopes and contrive a murder that would look like an accident. Maybe the man would insult him, enrage him to a point where instinct would take over, swamping all hesitation.

Whatever he did that day, Robert knew that he was not going to make it any kind of a duel. It was punishment he was after, not a symbol of honor. He closed his eyes and envisaged himself finishing the man off in some isolated place, hidden from all eyes by the enveloping cloud — how the finish would come he didn’t know. Somehow. Then he would pull the body off into the forest, leave it there for the snow to cover, for weeks, months (VICTIM OF SKIING ACCIDENT DISCOVERED BY FARMER TWO MONTHS AFTER DISAPPEARANCE), then get out of the country fast, divulging nothing to anyone.

Robert had never killed a man. During the war he had been assigned by the American Army as part of a liaison team, to a French division, and, though he had been shot at often enough, he had never fired a gun in Europe. When the war was over he had been secretly thankful that he had been spared the question of whether or not he was capable of killing. Now he understood — he had not been spared. The question was still open. His war was not over.

And if he didn’t kill — then what? Get the man alone, beat him to the ground, kick in his head with the big, heavy ski boots, leave him disfigured, marked for life with a broken face to bear witness to the vengeance he had so thoroughly deserved?

Maybe that, Robert thought; maybe that. Let him go to the police and complain. I would like that. He had a feeling that no matter what happened, the man would keep the police out of it if he could.

So, Robert decided, follow him. See what develops. Don’t let him out of your sight. Let what happens happen.

And swiftly — it had to happen swiftly, before the man realized that he was the object of any special attention, before he began to wonder about the American on his tracks, before the face of the skinny 14-year-old boy on the dark mountain in 1938 emerged in his memory from the avenging face of the grown man before him now.

“Say, Robert.” It was Mac’s voice finally breaking into his consciousness. “What’s the matter? I’ve been talking to you for thirty seconds and you haven’t heard a word I said. Are you sick? You look awfully queer, lad.”

“I’m all right,” Robert said. He made a great effort to make his face look like the face of the man Mac had skied with every day for a week. “I have a headache. That’s all. Maybe I’d better eat something, get something warm to drink. You go ahead down by yourself.”

“Of course not,” Mac said. “I’ll wait for you.”

“Don’t be silly,” Robert said, trying to keep his tone natural and friendly. “You’ll lose the Contessa. Actually I don’t feel much like skiing any more today. The weather’s turned lousy.” He gestured at the cloud that was blanketing the mountain. “You can’t see a thing. I’ll probably take the lift back down.”

“Hey, you’re beginning to worry me,” Mac said anxiously. “I’ll stick with you. You want me to take you to a doctor?”

“Leave me alone, please, Mac,” Robert said. He had to get rid of Mac. If it meant hurting his feelings he’d make it up to him someway later. “When I get one of these headaches I prefer being alone.”

“You’re sure now?” Mac asked.

“I’m sure.”

“OK. See you at the hotel for tea?”

“Yes,” Robert said. After murder, he thought, I always have a good tea. After murder — or whatever. He prayed that the Italian girl would put her skis on and move off quickly once they got to the top so that Mac would be gone before he started off after the man in the black cap.

The cabin was swinging over the last pylon now and slowing down to come into the station. The passengers were stirring, arranging clothes, testing bindings in preparation for their descent. Robert stole a quick glance at the German. The woman with him was knotting a silk scarf around his throat with little wifely gestures. She had the face of a cook, splotchy, with a red nose. Neither she nor the man looked in Robert’s direction. I will handle the problem of the woman when I come to it, Robert thought.

The cabin stopped, and the skiers began to disembark. Robert was close to the door and was one of the first out. Without looking back he walked swiftly away from the station and into the shifting grayness of the mountaintop. The mountain dropped off in a sheer, rocky face on one side of the station, and Robert went over and stood at the edge, looking out. If the German for any reason happened to come near him, to see how thick the cloud was on that side or to judge the condition of the snow on the Kaisergarten, which had to be entered farther on, but which cut back under the cliff lower down where the slope became more gradual, there was a possibility that a quick move on Robert’s part would send the man crashing down to the rocks 100 meters below, and then the whole thing would be over. Robert turned and faced the station exit, searching the crowd of brightly dressed skiers for the Afrika Korps cap.

He saw Mac come out with the Italian girl. He was talking to her and carrying her skis, and the girl was smiling warmly. Mac waved at Robert and then knelt to help the girl put on her skis. Robert took a deep breath. Mac, at least, was out of the way. And the American group had decided to have lunch on top and had gone into the restaurant near the station.

The Afrika Korps cap was not to be seen. The German and the woman had not yet come out. There was nothing unusual about that. People often waxed their skis in the station where it was warm or went to the toilets downstairs before starting down the mountain. It was all to the good. The longer the German took, the fewer people there would be hanging around to notice Robert when he set out after the man.

Robert waited at the cliff’s edge. In the swirling, cold cloud, he felt capable, powerful, curiously light-headed. For the first time in his life he understood the profound, sensual pleasure of destruction. I think I can do it, he thought; I really think I can do it. He waved gaily at Mac and the Italian girl as they moved off together on the traverse to one of the easier runs on the other side of the mountain.

Then the door to the station opened again, and the woman who had been with the German came out. She had her skis on, and Robert realized that they had been so long inside because they were putting their skis on in the waiting room. In bad weather people often did that so they wouldn’t freeze their hands outdoors on the icy metal of the bindings. The woman held the door open, and Robert saw the man in the Afrika Korps cap coming through the opening. But he wasn’t coming out like everybody else. He was hopping, with great ability, on one leg. The other leg had been cut off at mid-thigh. To keep his balance the German had miniature skis fixed on the ends of his poles, instead of the usual thonged baskets.

Through the years Robert had seen other one-legged skiers, veterans of Hitler’s armies who had refused to let their mutilation keep them off the mountains they loved, and he had admired their fortitude and skill. But he felt no admiration for the man in the Afrika Korps cap. All he felt was a bitter sense of loss, of having been deprived at the last moment of something that had been promised him and that he had wanted and desperately needed, because he knew he was not strong enough to murder or maim a man already maimed, to punish the already punished, and he despised himself for his own weakness. Now he understood something else too. He understood why the German had been so carelessly loud in expressing his contempt for the Americans in the cabin. His severed leg conferred on him a cripple’s immunity, and, cynically, he had enjoyed it to the full.

Robert watched as the man made his way across the snow with crablike cunning, hunched over the poles with the infants’ skis on their ends. Two or three times, when the man and the woman came to a rise, the woman got behind the man silently, and pushed him up the slope until he could move under his own power again.

The cloud had been swept away, and there was a momentary burst of sunlight. In it Robert saw the man and the woman traverse to the entrance of the steepest run on the mountain. Without hesitating, the man plunged into it, skiing skillfully, overtaking the more timid or weaker skiers who were picking their way cautiously down the slope.

Dully Robert watched the two of them descend the mountain, the man hideously graceful, wounded and invulnerable, and soon the couple became tiny figures on the white expanse below. Now Robert knew there was nothing to be done, nothing more to wait for except a cold, hopeless, everlasting forgiveness.

The two figures disappeared out of the sunlight into the solid bank of cloud that cut across the lower part of the mountain.

Then Robert went back to where he had left his skis and put them on. He did it clumsily. His hands were cold because he had taken off his mittens in the téléférique cabin in that hopeful and innocent past 10 minutes ago when he had thought the German insult could be paid back with a few blows of a bare fist.

He went off fast on the run that Mac had taken with the Italian girl, and he caught up with them before they were halfway down. It began to snow when they reached the village, and they went into the hotel and had a hilarious lunch with a lot of wine, and the girl gave Mac her address and said he should be sure to look her up the next time he came to Milan

Vintage Advertising: How Much Do You Know About Cracker Jack?

According to legend, a salesman accidentally coined the name for the Rueckheim brothers’ delectable snack food. After sampling the peanut-popcorn-and-molasses combination, he declared, “That’s a crackerjack,” using an old term for “first rate.”

The name stuck. And the packaging was also first rate — a cardboard box lined with wax paper so the contents stayed fresh. In 1908, Cracker Jack was immortalized in the song, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” which is estimated to be the third most frequently sung tune in America. In 1919, the company added a mascot, Sailor Jack, modeled after Frederick Rueckheim’s grandson Robert. When the boy died of pneumonia, his image was kept on the box as a lasting tribute.

Children appreciated that Cracker Jack cost only a nickel for over five decades. But they were especially drawn to the prizes in the box. In the course of 100 years, Cracker Jack delivered over 23 billion tiny prizes — puzzles, dolls, books, whistles, compasses, and hundreds more. Today, sadly, that tradition has ended, but you can scan a digital code inside the box — well, it’s a bag now — to play a “baseball-inspired mobile digital experience.” Oh, well. At least Sailor Jack’s image remains on the front of the package.

An Automobile Genius on the Secrets of Innovation

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

This year the company for which I work — General Motors — is celebrating its 50th anniversary. For 40 of those years I have been a consulting inventor for the company. We sometimes hear it said that necessity is the mother of invention. If that were true, then it might be said that for the last several decades I have been working my head off because of necessity.

I can’t go along with this maxim altogether. Necessity was certainly not the mother of the airplane. At the time the Wright Brothers were inventing the airplane there was no widespread clamor to fly. People did not believe it was necessary. The Wright Brothers just thought they knew how they could do it and so they went ahead and thereby opened up a huge new field.

It might be argued that it has not been necessary to invent the automobile or to improve it through many inventions in the last 50 years. We would have lived with no more than the horse and the buggy. But I believe we are all thankful for 50 years of improvement in the automobile, and I am sure we will keep trying for more improvement just as hard in the next 50 years.

I am a little afraid of reminiscing. But to measure the possibilities of the next 50 years, it may be worth looking back over the last 50. It is amazing what the invention and development of the automobile and its applications have done to influence the habits and customs of our people in this period. Since 1908, manufacturers in this country have produced 160 million motor vehicles, and today the automobile creates 10 million jobs in highway-transport industries, more than one of every seven existing jobs. It has created a quarter of a million businesses like motels and service stations, and influenced the building of 2 million miles of roads. It has made deep changes in how people travel, how farmers grow and market crops, and where schools are built.

The automobile industry pays about $8 billion a year in taxes. Almost one quarter of the retail price of each vehicle is tax money. This is an enormous burden, yet the automobile industry has produced the greatest transportation system the world has ever seen. One of the most important reasons for this growth has been the industry’s willingness to change its product and its production methods to suit customers’ demands. The industry has been willing every year to design and build new tools which can produce more and better cars.

I do not advocate change for the sake of change, nor do I say that a new thing is necessarily better because it is new or suddenly popular. But if there is one thing the automobile has taught Americans in the last 50 years it is to expect constant improvement in the product. In America we must constantly change and improve or fade away.

Too often people believe that change comes about through the simple process of handing a problem to a research laboratory where an answer is produced mysteriously but promptly. There is no such magic in research. Discovery and invention come only by hard work, disappointments, innumerable failures, and very often the consumption of much time and money. Research is based on patience, skill, and practice and more practice. A theoretical physicist may develop an accurate formula for the curve of a baseball in flight, but it takes a pitcher years of practice to control the curve.

Since its inception the automobile industry has worked and practiced to lift the automobile from the status of a rich man’s toy. It was only a few years before General Motors was born that Ransom Olds discovered one of the secrets of mass production — progressive assembly. And it was just 55 years ago that Henry Leland, who was then head of Cadillac, demonstrated that automobile parts could be made interchangeable. These two developments were basically important to the automobile, but they alone did not make the product a perfect one. Leland understood this very well.

At that time the automobile was cranked by hand, which was not a job for women and usually meant they were relegated to the backseat as passengers. Hand-cranking was not popular with men, either, since there was a constant risk of broken arms. Leland disliked this imperfection and when a dear friend of his died as the result of an accident during hand-cranking, he sent me an invitation to visit Detroit and discuss the problem of making car-starting a safer operation.

This was one time when I might agree that necessity mothered an invention, because in a moment of weakness I told him that I thought a car might be cranked with an electric motor driven from a storage battery. Having made the rash statement it was up to me to produce it, and I worked for months in my small laboratory which was part of a barn in Dayton, Ohio. Eventually we did produce an electric starter, a modification of which became production equipment on the 1912 Cadillac.

This outraged the electrical-equipment engineers. They looked at their formulas and said that it was impossible, that we would need batteries and an electric motor larger than the engine itself and wires five times as heavy as we used. But they were thinking about continuous-running electric equipment. But we were not planning to transmit current 100 miles or work our electric motors 24 hours a day. We wanted a spasm of power, a big torque for a short time, and after the engine was turned over and started, the little starting system could lie back and rest and be recharged for the next start. So we disregarded the power rules and made driving possible for millions of people who couldn’t or did not want to hand-crank an engine.

Ten years later we could manufacture automobiles at the rate of one a minute, but they were not getting to the customer at that rate. It took one or two weeks to paint the car because the system that had been used on carriages was being applied to automobiles. The increased production resulting from the growing demand for closed cars could not possibly be met by using the old finishing methods.

Eventually the answer was found in the chemist’s test tube, although the you-can’t- do-it boys were on our necks all the time telling us we were wrong. Now, instead of several weeks to paint a car, it takes an hour to spray on the required number of coats of quick-drying, durable, colorful lacquer. The bottleneck to customers’ demands was broken.

In this business of ours you never solve one problem without, nine times out of 10, coming face to face with another one. After we had put electric starting, lighting, and ignition on the Cadillac we became sitting ducks for attacks aimed at us by the people whose toes we had stepped on when we electrified the automobile. In those days the quality of gasoline was hit-or-miss and the quality went down as automobile production went up. Engines began to knock all over the place. Naturally our competitors blamed the increasingly prevalent knock on our new ignition system.

In order to defend ourselves it was up to us to find out what really did cause knock. It was a problem that had also arisen with the Delco farm-lighting systems which I had originally devised so that my parents could have light and running water on their Ohio farm. To do this job we put a fellow inventor, Tom Midgley, to work studying this annoying matter of knock which was keeping us from increasing the compression in our engines. Happily neither Tom nor I was an orthodox chemist or thermal engineer, so we were wholesomely ignorant of the obstacles. We had a fine chance to make some informative errors in this field.

In the period before World War I, we had found out first just when knock occurred in the combustion chamber. It was after the ignition spark; and not before, as everyone had supposed. With this knowledge in hand we started a series of experimental treatments of the fuel. I remember that the first one was the introduction of coloring matter based on the heat-retaining characteristics of a certain flowering plant. We got a promising result, only to learn by checking with another substance that color had absolutely nothing to do with it. Nevertheless we learned something from that, and as we went on to test other additives a pattern of behavior began to appear.

The motoring public will never know how lucky it was that we did not stop in the middle of our experiments. The pattern indicated that the compounds of the heavier elements were most effective in squelching knock. We found two or three that were so good we might have been satisfied with their performance if it had not been for one thing — they smelled terrible. They smelled so bad and the odor was so lasting that the men in the laboratory who handled them were on the verge of becoming involuntary hermits. They didn’t dare go to the movies. But with the pattern leading us in the direction of the heavy elements, I suggested that we take a big leap and try the very heavy metal — lead.

The result of that leap was a whole bookful of trouble — and tetraethyl lead antiknock gasoline, which Midgley and his boys worked out and which is now known as Ethyl to everyone. Before we perfected Ethyl for widespread use, we had to develop a method of extracting huge quantities of the element bromine from the ocean. The chemists again told us this was impractical, since there is only one-tenth of a pound of bromine in a ton of sea water. But we found a way, and now we extract 120 million pounds of bromine from the sea annually. If you want to put a value on the result of our long hard search, in which the entire oil industry cooperated, you can do so in three ways. The superior fuel made possible more efficient high-compression engines. It permitted us annually to leave 25 billion gallons of fuel in our underground reserves which otherwise would have been burned. And at retail prices of gasoline the American motorist has been saving $5 to $8 billion a year.

You can see from just these few examples that the automobile industry was teethed on trouble. Complacency has no place in this business. You have to break out of the ruts if you want to survive. The fact that of about 2,500 makes of automobiles that have appeared only a handful are in existence today is a good illustration of what can happen if you design to suit yourself and ignore the wishes of your boss — the customer.

I am a great believer in the “double profit” system. The producer must make a profit to keep in business, but the customers’ profit must be ever so much greater. If you don’t believe some of these modern necessities, comforts, and conveniences have a definite value to you, just try doing without them. Suppose you were suddenly deprived of your car, electric lights, and power, or the telephone, radio, or television. What would you give to have them back?

—“Future Unlimited,”

The Saturday Evening Post, May 17, 1958

Floating Toward Ecstasy: How One Man Overcame His Scuba Fears and Learned to Let Go

The fish are fine and all that, but the epiphany is the sensation of floating, of weightlessness. After two days in dive school, I know the term is neutral buoyancy, the state in which you are neither rising nor sinking, but that’s just the science. It’s like explaining why a fish is luminously blue, which doesn’t quite get to the wonder of it. Broad leaves of soft coral bend in the current, bowing in praise of my effort to inhabit their world. I hear the soothing susurrations of my own breath, and submersed just 40 or so feet below the surface, I have a feeling of mindfulness, of intense alertness within this aquatic womb.

“We ourselves see in all rivers and oceans,” wrote Herman Melville in Moby-Dick. “It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life.” Divers require no explanation. “I live to dive,” my instructor, Steven, liked to say. He was a Dutch expat who came for a visit when he was transfixed by the lapis lazuli sea in Playa del Carmen and decided he’d never leave.

When Steven first told me, I could see the water but I couldn’t relate, because after two days of watching videos and practicing in the pool of the Tank-Ha Dive Center, my first open-water dives made me want to go home. I hadn’t equalized my ears properly and felt the first atmospheric pressure like a vice-grip inside my skull. Once that resolved, an acute thought replaced it, that my life — my parents’ son, my wife’s husband, my children’s father — was hanging on a rubber thread linking my mouthpiece to my tank. One mistake or malfunction would set in motion a lot of logistics, such as how to transport the body and what kind of services and eulogies and, gee, I had meant to increase my life insurance, hadn’t I? It didn’t make me inclined to feel thanks for all the fish, and I even felt unkindly toward the divers who had all promised, every last one of them, “You’re gonna love it!” as if they’d been pledged to repeat the line as part of some fraternal code.

When I climbed back onto the boat 40-some minutes later, I was stressed, tired, and relieved, though the relief passed quickly as the waves started to make the boat, and my belly, surge and roll. Suddenly, even the briny smell of the sea was an unpleasant odor. “I’m feeling a little seasick,” I told Steven.

“You’ll be all right once we get back into the water,” he said.

Would he think less of me if I threw up or broke down? I might do either, or both.