Ben Franklin Used Fake News

It may seem like our political climate, in which politicians and journalists are accused of inventing phony stories, is unprecedented. Yet there are similarities to past events, and some of the perpetrators of early political chicanery may surprise you.

For example, in 1782, while still representing the United States in Paris, Benjamin Franklin printed a fake edition of an actual Boston newspaper, The Independent Chronicle. Amid the fictitious ads and articles, Franklin inserted a made-up story about the massive slaughter of white settlers on the frontiers of New York. Native Americans, in the service of the British forces, had collected 700 scalps from men, women, children, and even infants, Franklin lied.

When the news reached America, it was reprinted in papers throughout New England. The story helped stiffen American resistance to the British, who were now seen as using Indians to terrorize settlers. Released in Paris, the story also helped sway European opinion against England.

Franklin’s “fake news” was just the start of a long tradition in American politics.

As we noted in “Crude Language on the Campaign Trail,” presidential campaigns have often been marked by fabricated stories and synthetic scandals. Even after the race, the slander often continued.

In 1939, Stephen T. Early, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary, shared several examples of disinformation campaigns directed against the president.

Roosevelt enjoyed broad support among voters, particularly in the early years of his presidency. But he remained a controversial leader for many Americans. Some of his opponents hoped to blacken his reputation with reports of corruption or dishonesty in the White House.

In a file he marked “Below the Belt,” Early gave examples of these fake news stories. Some hinted at sinister, international conspiracies implicating Roosevelt, a foreign-born Supreme Court justice, and labor leaders, among others. One story claimed President Roosevelt had prevented the capture and trial of the true kidnappers of the Lindbergh baby. The kidnappers, it argued, were protected by the president and were still kidnapping and murdering.

Early wondered, as many Americans do today, “just how gullible do these muckrakers think the American people are?”

Roosevelt, however, refused to be baited by these stories. When a publisher reported that the president had fallen into a coma, he offered to print a retraction if the White House issued a denial. All he got was silence. Roosevelt refused to reward him with more media attention.

Unfortunately, in our era of 24-hour information, ignoring even flagrant fake news doesn’t seem to be an option. What and whom are we to believe? In both the literal and figurative sense, we are left to our own devices.

“The Monster and the Infant” by Paul Gallico

Although he is most remembered for his novels The Poseidon Adventure and The Snow Goose, Paul Gallico began his career as a sportswriter for the New York Daily News. Gallico was published in the Post continually throughout the 1940s and ‘50s. His story “The Monster and the Infant,” (1942) about a high-stakes golf championship, showcases Gallico’s folk tale writing style. Above all, he considered himself a storyteller.

Originally published on September 19, 1942

Funny how the mind works, isn’t it? You’ll see something in the papers that brings up memories and, bingo, back you go, living it all over again, as though you were sitting in a movie and seeing it on the screen.

It was just like that when I picked up The Morning Blade the other day and saw that picture on the front page and the story that went with it. It took me back eight or ten years, and presto! there I was on the eighteenth tee at Braewick, for the finals of the National Amateur Championship.

The handsome Infant, chalk-faced from strain and worry, was just setting to hit that life-or-death drive. Behind him, his back turned, a sour look on his big red face, stood the Monster. Down the fairway running between woods to the green stretched ten thousand spectators in an ugly mood.

There were the worried golf officials trying to calm the gallery while state troopers and harried marshals penned them behind ropes. There was that blot on an otherwise beautifully manicured landscape, by the name of J. Sears Hammett. And there was also yours truly, William Fowler, Esq., getting ready as usual to hold that sack.

Brother, it sure took me back, and I can’t say I enjoyed the trip. Because that was one tournament where your Uncle William took it right on the chin.

I know. You’ve heard that one before. And then it goes on to tell how in the end I wind up signing the star golfer for my outfit, A. R. Mallow & Co., makers of Far-Fli Woods, Tru-Distance Irons, and the Thunderbolt golf ball, straighten out the course of true love, and foil the villain, the same being that aforementioned understudy to a cottonmouth, J. Sears Hammett.

Not this one, chum. Maybe it’s time I let you in on one of my lemons.

Remember the finals of the Amateur back at Braewick between Francis Ogden Medford, of the Social Register and Boston’s Back Bay, and Ted Wilson, the high school kid from Lincoln Cross, Iowa? I thought you would. But what you don’t know is that it cost the good name of William Fowler, plus two hundred and fifty pesos in cold cash. For two years after, my best friends wouldn’t speak to me. And I used to be a pretty popular guy before upsetting those frijoles.

Why, I couldn’t even pick up a golf game with the club dubs, I was that shunned. Me, the sassiest advertising-promotion manager in the golf-equipment business, a pariah. And all because if it hadn’t been for my — Well, never mind that now. Let’s get on to the gruesome details.

What was I doing at the Amateur Championship? Just buzzing around to meet old friends, follow the matches, and help out with the lying in the locker room afterward. It was supposed to be a kind of vacation. Some vacation!

Those were still the dear, daffy days when we could run a temperature over a couple of comparative strangers beating a genuine rubber ball cross country with assorted hardware, and our idea of a hero was someone who could tank a putt from thirty feet when the chips were down. And did the country get heated up over young Teddy Wilson!

When the tournament started on Monday morning with the qualifying rounds, nobody had ever heard of Ted Wilson or Lincoln Cross, Iowa. By five o’clock of the same afternoon, that situation had been considerably remedied when he steamed in with a 67-68 for 135, to win the medal by five strokes and break the course record twice. And by Thursday, when he had ripped his way into the quarter-finals by knocking off four of the best amateur golfers in the game, there wasn’t anyone in the U. S. A. and possessions who didn’t know all about Ted Wilson. The newspapers took care of that.

You couldn’t blame them. He was a story. Sixteen years old, with dark, curly hair, apple cheeks, a sensitive kisser coupled to a square fighting chin, and those deep-set gray-green eyes under long lashes that had the hearts of females in the gallery from seven to seventy doing nip-ups, he was Young America. That was Ted Wilson — everybody’s kid, or what everyone hoped his kid would be like someday.

He was as poor as a church mouse’s second cousin, and supported his widowed mother in Lincoln Cross, Iowa, caddying, and doing odd jobs after school. I’m only refreshing your memory, since you read it all in the newspapers at the time: How he got to the tournament by hitchhiking across the country, sleeping in barns on the way, and arriving at Braewick with a canvas sack of rusty clubs, eleven dollars, and two clean shirts.

He got a room for two bucks a week about five miles from Braewick, and walked to and from the golf course every day. He lived on hamburgers and milk, and wouldn’t take a gift or a handout from anybody. Every night he washed out his shirts and ironed them in the morning before going to the club. Wow! Did the sob sisters go to town on him!

And those clubs of his! No two alike; they were patched, taped, warped, and held together with wire. He’d never had a new ball in his life, and used twenty-five-cent repaints. He played in sneakers because he couldn’t afford spikes. He would have carried his own bag if they had let him, but the day after he got there, old Pete the Grouch, assistant caddiemaster of Braewick, took his bag for nothing. He was that kind of a kid. Everybody fell in love with him.

And golf? Brother! It was just like the days when Bob Jones first popped over the horizon. From the first moment I saw that beautiful swing I followed him around in a kind of daze, hoping that maybe if I watched him long enough, some of his golf might come off on me. The first three days of that tournament were just like a beautiful dream for your Uncle William. Fun, no worries, and supergolf.

And then, blooie went the dream!

It went up with a loud bang when The Blade came out Thursday morning, the day of the quarter- finals, carrying an interview with Ted by Una Odell, one of the damper sob sisters. I still have the clippings, and I quote:

I asked him whether he intended to go to college when he finished high school.

“Gee, Miss Odell,” he said, and his wonderful deep gray eyes turned serious for a moment, “I’d like to go to college, but I can’t. We’re too poor. If I win the championship I’m going to turn professional right away and get a job, if I can. Golly, Miss Odell, I’ve just got to win it.” And here a look of tragic sadness came over his handsome young face, and his childlike mouth quivered a little. “We haven’t been able to pay the interest on the mortgage since dad died, and we’ll lose the house if I can’t make some money. But if I win the title, maybe I can get a good job with some club, and…”

Maybe! That was just putting it mildly. The facts in Una’s bilge were straight. The balloon went up shortly after. There were three telegrams on my plate when I came down to breakfast that morning:

IF WILSON WINS DO NOT FAIL TO SIGN FOR A.R. MALLOW & CO. STAFF. WORTH THOUSANDS IN PUBLICITY TO US. A.R. MALLOW, PRESIDENT.

EXERT ALL INFLUENCE OFFER EVERY ASSISTANCE TED WILSON WIN CHAMPIONSHIP MAKE ANY OFFER WITHIN REASON. ADVISE AND HELP HIM, INSTILLING FEELING OF GRATITUDE TOWARDS OUR COMPANY. WHOLE COUNTRY TALKING ABOUT HIM. IMPERATIVE YOU SIGN HIM IF HE WINS. WILL PAY SALARY AND BONUS ALSO MORTGAGE ON HOUSE. STRONGLY URGE YOU LEAVE NO STONE UNTURNED. WE ARE PREPARING ADVERTISING CAMPAIGN BASED ON WILSON. GO TO IT. A.R. MALLOW, PRESIDENT.

RE MY FIRST TWO WIRES. DON’T FAIL. MALLOW.

That was the Old Man for you. What he didn’t know about golf tournaments, if laid end to end, would reach from here to California. “See that he wins.” Huh! The Amateur Championship! What was I supposed to do, slip Mickeys into the soup of his opponents, or jog their elbows when they went to putt?

I tucked away a double of ham and eggs and coffee to give me strength and went out to try to tie an option on the kid in case he should come through. I found him finally off in a corner of the locker room, surrounded by the one guy in the world who can give the itch to poison ivy, J. Sears Hammett, advertising-promotion manager of the Fairgreen Company, our biggest rivals in the golf-equipment manufacturing field.

He had the youngster pinned up against a locker and was giving him that codfish eye and grade-B clabber smile. Before I could get in a word, he said, with that nasty, horse-cough laugh of his, “Ha-argh, ha-arrgh! If it isn’t my old friend, Bill Fowler, late again as usual. I’ve just finished telling my young friend here what Fairgreen is going to do for him. Too bad about you, Fowler. Asleep at the switch. Ha-argh! He’s practically signed with me, haven’t you, Teddy? Ah, what happy times we have over at Fairgreen.”

The kid blushed under the fuzz on his cheeks and stammered, “Well, gee, sir, I — I didn’t exactly. I mean — ”

I could see right away that Hammett was bluffing, but the kid was too decent and well-mannered to show him up in front of me.

Hammett waved a finger at him. “Ah-ah! Now, Teddy. I shall hold you to your word. Remember what I promised you.”

“Oh, boloney,” I said. “I don’t know what he promised you, Ted, but Mallow wants you if you win this thing and we’re prepared to double any offer this man made you right now, and what’s more — ”

“Gee, sir,” Wilson began, “that’s wonderful, but — ”

Hammett began to wave his arms and howl. “Don’t you listen to him, Teddy. You admit I spoke to you first. That’s as good as a contract. We’ll — ”

“Hammett, you’re a cockeyed — ” was the best I could come up with, when Ted extricated himself from the corner, saying: “Say, look, you’re both very kind, but I can’t sign with anybody until I win and the tournament’s over, or I’ll get in Dutch with my amateur standing. I just can’t. I have to go out and play golf now. I’ll see you both later. G’by.” And he ran down the aisle of the locker room and out the door.

I said to Hammett, “You’re a fine lug, trying to bully a sweet kid like that.”

“Ha-arrrgh! I suppose you think you’re going to get him.”

“You can just bet we’re going to get him.”

“Ahem. I take it you would wager on it.”

“Ya-a-as. I wanna bet. Make it easy on yourself.”

“I don’t bother with chicken feed, Fowler. Care to risk two hundred and fifty?”

“You’ve got a bet.”

“Okay, Mr. Sucker. Two hundred and fifty you don’t sign Teddy Wilson. Be seeing you out on the golf course. So long, sap!”

I guess I’ve told you there’s something about J. Sears Hammett that puts me right off my chump. When I’m face to face with that patent leather louse, getting that buck-tooth sneer out from under those six bristles he wears for a mustache, my brain addles like an egg dropped into a concrete mixer.

And this was no exception. Two minutes after he had gone out, I was still standing there banging myself on the brain box with the heel of my hand, and moaning: “Stung! Stung again!”

I had just realized what Hammett had put over. Like a copper-riveted, triple butt-welded boob, I had bet two hundred and fifty of my hard-earned piastres that we would sign up Wilson. And he hadn’t even won the tournament yet. He still had his two toughest matches to play. If he lost, nobody would sign him. I had given Hammett even money on a five-to-one shot, because even if he came through, I still had to put the deal over with him. That’s Fowler.

Maybe you think it was too early in the morning to start inhaling tall ones, but brother, I needed a couple. Of all the prize clowns, yours truly topped the bill. After the medicine had taken hold I went out to look at the bracketing on the scoreboard to see what my chances were of Ted Wilson winding up with the championship. It didn’t take much of a look, either. It was sure to be Ted Wilson against the Monster in the finals.

Of course you may not know him by that name, but just as the sports writers nicknamed Wilson the Infant, they hung the tag of the Monster onto Francis Ogden Medford, millionaire bachelor, socialite, blueblood amateur sportsman from Boston’s Back Bay. Nobody liked Mister Social Register Medford.

Most of my information on Medford came from the sports writers, whom he avoided and invariably refused interviews. They pegged him as a platinum-plated snob and stuffed shirt. And just hanging around the tournament, I could make out that he wasn’t exactly an ideal companion on a golf course.

He was as hard as nails, and a pretty tough customer, I guess, because he piloted a Spad in France in the last war. You had to hand him that.

At the start of a match he never more than nodded to an opponent. He shook hands at the finish, and if anybody got more than a grunt out of him at any other time during a round, it was scored as a double eagle. But I never saw a guy concentrate more on the game. His application was terrific. He played like a machine, and he played all out to win, which is all right in my book, except that I like to think of golf as a kind of sociable game.

But not Brother Medford. He didn’t seem to have any friends around the clubhouse, and as soon as it was over he would climb into his sixteen-cylinder chariot, piloted by a couple of Senegambians in livery, and buzz off to parts unknown. I told you he had a hot golf game, didn’t I? He’d been runner-up several times in previous amateur championships.

I was asleep at the switch again, and J. Sears Hammett snagged the Infant at noon recess and bought him lunch. I passed them on the terrace and Hammett was filling the kid full of chicken salad, ice cream, cake and lemonade. As I went by, J. Sears gave me that triple-fang smile which meant that he was feeling cocky, and said, “Haw-haw, Fowler. Sorry I can’t ask you to join us, but there’s no room. Anyway, Teddy and I want to talk over his contract with Fairgreen. So long, old boy, and never mind the check when you pay off. I’ll take cash. Haw-haw!”

I had one of my pure strokes of genius when I saw what he was feeding the kid, and went to the locker room shop and bought a box of indigestion tablets. It was a good thing I did, too, because halfway around in the afternoon the Infant got sick as two pups and blew four holes in a row, going three down to the Canadian champion. I went up to him and slipped him a couple of tablets. He felt better right away and began to pick up again.

He said, “I’m mighty grateful to you, sir. I don’t know what I’d have done if you hadn’t come along.”

Maybe you think that didn’t make me feel good. I stuck with the boy the rest of the round and did what I could to help him out by keeping too-enthusiastic galleryites and sob sisters off his neck. He just squeaked through with a birdie on the eighteenth to go into the finals the next day.

Fellow students, do you remember the papers that Saturday morning when Francis Ogden Medford, of Boston, and Ted Wilson, of Lincoln Cross, Iowa, met for the amateur championship? They pulled out all the stops, didn’t they? Without actually calling Medford a safecracker and second-story man, they made it clear that the forthcoming battle for the Amateur Golf Championship was the final and decisive struggle between wealth and poverty, freedom and tyranny, Good against Evil.

Of course, you couldn’t blame the press entirely. The contrast was right there before your eyes: Medford equipped with the best that money could buy — forty-dollar shoes, sharkskin slacks and Irish linen shirt, as immaculately groomed as a wealthy man can be. His personal African toted a tooled-leather sack of mallets that had been handmade and designed especially for him, each one a masterpiece of matching and balancing; he played the best and fastest ball on the market, each one neatly stamped with his initials, F.O.M.

And there, on the other hand, was the Infant, in sneakers, khaki pants and cotton shirt, with a torn canvas bag of miscellaneous warped, mismated hardware, and a handful of cheap, repaint golf balls that wouldn’t go over two hundred and thirty yards if you fired them out of a trench mortar. The papers didn’t miss any of that either.

The last time the country got as steamed up over who was going to win a big sports event was when Helen Wills played Suzanne Lenglen. Only this one was going on right under our noses, where the folks could get out and hiss the villain.

They did too. In the key of F. By the time the Infant and the Monster had finished the morning round of eighteen all square and had called a truce to take aboard some groceries, that golf match was a shambles and the unhappy officials had sent out a hurry call to the state troopers and fly cops to come over to the golf course and maintain law and order for the last holes that would decide the championship.

I can give you a picture of it in one line. Not even the gamblers were rooting for Medford.

Wilson and Medford played ding-dong golf in that morning round, but the gallery was brutal. There were nearly ten thousand of them out there, and they believed all the stuff they had read in the papers. Besides, they were seeing it with their own eyes: Medford, surly, taciturn, big and beefy, tough, conceding nothing, applying the rules and making them stick, never so much as by a smile or a gesture acknowledging anything the Infant did, while Ted battled on valiantly, the perfect little sportsman, applauding Medford’s good shots, and there were plenty, and conceding putts as much as a foot away from the hole. The Monster conceded nothing. He made Ted putt them out from two inches away. When we got onto that first tee after lunch for the final round, that gallery was loaded for Siberian bear.

Hammett and I were following the match together. He wasn’t exactly the kind of companion I would pick unless I were locked in the cooler with him, but we both had the same objective, which was to root that kid through.

Then the series of stymies happened. The Monster laid the Infant three stymies in four holes, and won them all. Of course it was only a coincidence, because anyone who knows anything about golf can tell you that if a man can putt well enough to lay three dead stymies he can also putt well enough to drop them into the can, which is a lot more conclusive. But that wild-eyed mob booed and hooted and yelled.

Hammett was trying to show off to the Infant by shouting with the rest: “Make him stop that! Bad sport! For shame!” to the kid’s distress. The behavior of the gallery toward his opponent was upsetting him.

I said to Hammett, “Oh, shut up, and don’t be an ass! You’re making Ted nervous. This isn’ t a prize fight. It’s supposed to be amateur golf.”

“Amateur golf, my eye,” said Hammett nastily. “It’s business, and I’m protecting my client. Of course, if you want to pull for Medford — ”

What was the use?

Ted was one down on No. 9 and lay on the green with a chance for a half, The Infant addressed his ball to putt, when he suddenly straightened up and stepped back.

“I’ve got to call a stroke on myself,” he said. “I moved the ball more than half a turn.” Nobody had seen it happen but the Infant himself.

Hammett was livid. “The young idiot,” he stormed. “He could have got away with it. We’ll soon cure him of tricks like that at Fairgreen.”

I was sick to see Ted lose that stroke and the hole, too, but, doggone it, I was proud of him! That’s golf. If you start out by not cheating yourself, you’ll never cheat anybody else.

Out of the silence that fell over the crowd as they realized what the boy had done, came a man’s voice.

“I’ll bet the Monster’s going to take it, too, the big bum.”

Of course they didn’t know that Medford had no choice in the matter. But the Monster didn’t make matters any better by failing even to acknowledge the kid’s fine gesture. He simply picked up his ball, turned his back, and walked off to the next tee.

That angry gallery really got articulate. “Boo-o-o! Why, he didn’t even say thank you! Oh, you big fat snob!” You could tell they’d been reading those newspaper stories. A woman threatened Medford with her parasol and screamed, “Aren’t you ashamed of picking on a fine boy like that?”

After that, some of the coppers and marshals formed a ring around Medford and the match got on a little faster. The Infant really began to pour on the golf, pulled up even, and went one up on the Monster at the sixteenth, when he tanked a thirty-footer for a bird and the crowd went nuts.

I was beginning to figure already how I would get his name on the dotted line for A.R. Mallow & Co., when he ran into a piece of tough luck on the dog-leg seventeenth. He tried to carry the corner of some houses with that cheap ball, and pulled a little. The fore caddie didn’t see it fall, and the ball was lost.

It was lost, too, because ten thousand people tried to find it. You never saw such a trampling as that landscape caught. I saw the Monster glance at his wrist watch and say something to the referee, who nodded, immediately called time, and ordered the Infant to play another ball, which of course he did, a nice spanking shot, which, however, wasn’t going to do him much good.

When word got around the gallery that Medford had notified the officials that the five minutes allowed under the rules to find a lost ball had expired, that mob really began to boil. I had never seen cops on a golf course at a championship match before, but, believe me, comrades, I was glad to see them now. They did a lot of circulating around and the sight of the uniforms cooled the populace off a bit. Still, that didn’t help our side. Ted lost the hole and the two men walked up to the eighteenth tee all square.

That eighteenth was a sight too. The fairway was lined solidly on both sides with people, and they were banked twenty deep around the green, four hundred yards away. And you couldn’t hear a sound as the Monster stepped up to drive.

Strangely, this time, the gallery didn’t make any noise or try to rattle him. I guess the drama of the match had got them. But, boy, you could just feel it. Ten thousand souls concentrated on hating one man and wishing him into trouble.

They got their wish too. The Monster made the only bad shot of his entire round. He hit a whistling hook that curved for the thick woods on the left. The crowd scattered in all directions to let it go in, running right over the fore caddies posted there. And that ball went bye-bye too.

Then the Infant teed up his ball. Even before I heard the yell of delight from the partisans, I knew from the clean “snick” that it was a honey. It was low, hard and perfectly placed. It left him with an easy mashie shot to the island green.

The Monster strode down the fairway, headed for the rough. You’d have thought there was poison oak, smallpox and mustard gas in that woods the way the crowd kept away from the spot where the ball might be. The only ones looking for it were the caddies, officials, Medford, and young Ted. But the citizens had plenty to say.

“There, how do you like some of your own medicine now? . . . Hope you don’t find it… Hey, kid, let him find it himself, if he can… Two minutes! Two minutes!”

Somebody had made note of the time the search began and the spectators took up the chant: “Two and a half minutes! Three minutes… Three and a half!”

There was a lot of tangled underbrush at that particular spot in the woods. Hammett and I walked past it through the edge of the rough on our way to the green just as the crowd let out a joyous roar of “Four minutes!”

One more minute, and the kid was in. With that position, he was a sure thing to get a four to Medford’s five. Some of the color had come back into his face, as the seconds ticked off. Well, you couldn’t blame him. It was the luck of the game. He had taken it on the chin at the last hole. Now it was his turn to get a break when he most needed it.

The mob chanted, “Four and a half minutes.” The kid’s face was working. He was trying so hard not to look happy about it. The Monster was preparing to go back to the tee and drive another.

And that was when I saw the ball.

It was buried almost out of sight in a tuft of thick grass in the rough in a wide space between trees that gave a difficult but clear shot to the green. It hadn’t been found because no one had seen it hit a tree and bounce back.

Hammett saw me goggle and stare and spotted it at the same time. It was the Monster’s ball, all right, because down through the grass we could see the red stamped initials, F.O.M.

Hammett grabbed me by the arm hard. “Hah!” he whispered. “By gad! Teddy’s won. They’ll never see it there.”

I guess I was just the biggest fool in the world that day. But, you know, golf is a funny game. You either love it or you don’t. And if you do love it you like to see it played the way it’s written.

I knew it was only a matter of seconds before time would be called, but I certainly managed to think about a lot of things while they ticked off. Sure, I knew all about Medford and his money and social position, and that it was just a cup he was playing for, maybe to bolster his own ego. And I remembered Ted, too, and how much he needed that victory, and what it would mean to lose. I even had time to toss a thought at my bet with Hammett and the value it would be to Mallow & Co., in publicity, to snag the Infant.

But, dammit, they were playing for the amateur championship of the United States, and that’s more than just a bunch of words. It was an honor to hold it. And no matter what kind of a slob he might be, as long as he stuck to the rules and played the game, Francis Ogden Medford was just as much entitled to a fair chance to win it if he could as Teddy Wilson.

Anyway, we’d all gone cockeyed on that newspaper publicity. What did I really know about Medford? Bob Jones used to play with that sick expression around his mouth, and it was nothing but just plain nerves. Maybe Medford was a snob, but that was his business, too, though I’ve seen a lot of shy men accused of the same thing. And he was no more responsible for the position into which he was born than as Ted. He had taken an awful horsing around from that gallery without a single beef.

But the point I couldn’t get away from was that those two weren’t out there to see whether Ted Wilson could get a job as a professional and lift the mortgage on the old homestead, or Medford add another pot to his collection. They were there to settle who was the best amateur golfer in the country that day.

Yes. You guessed it. I did the sappy thing. I yanked away from Hammett, raised my arm, and shouted, “Found!”

Just in time, too, because already the crowd was beginning to chant, “Five minutes! Yah, yah, Medford.”

The Infant turned as white as his shirt. Gee, I felt rotten. Medford didn’t even say, “Thank you.” He just walked up to the ball in a kind of daze and began studying the lie. After a while he pulled out a No. 3 iron, whaled with all the power of his burly body, and spanked it out of there and up onto the green a foot from the cup.

My pal, J. Sears Hammett, sure was a help at that moment. He ran up to the Infant, pointing at me and screaming, “He did it! There’s the man who did it! That’s your fine friend. I told him to keep quiet. That’s the kind of a deal you’ll get from that Mallow outfit!”

The kid, with a tired and kind of sick look on his face, just said, “Oh, please, leave me alone,” and walked away.

He still had plenty of guts. He went up to his ball and hit a good shot up to the green, but it wasn’t good enough. He took two putts to the Monster’s one, and that was that. Francis Ogden Medford was the new amateur champion.

There was only a bare handful of people stayed around for the cup presentation ceremonies. And for just a moment, when Medford accepted the trophy, that curdled expression left his face and he smiled like a human being. He turned to the Infant, stuck out his hand, and said: “You played a fine game. Thank you.”

The kid grinned like a sportsman and replied: “Thank you, sir. I enjoyed playing with you. I learned a lot.”

Medford smiled again, and patted Ted’s shoulder awkwardly. His big beefy face was redder than ever. If it hadn’t been Medford, I’d have sworn he was blushing.

I wired Mallow and asked to be allowed to sign the boy anyway, because he was such a comer, and stuck around the wire tent until the answer snapped back:

R. MALLOW & CO. NOT INTERESTED IN RUNNERS-UP. FEEL YOU HAVE FALLEN DOWN ON THE JOB. A. R. MALLOW.

And so that tournament melted away into the litter of torn programs, sandwich wrappers, squashed drinking cups and paper admission badges. I told you it was one of my lemons, didn’t I?

That’s how it ended. Except that as I stood waiting for a cab to get back to town, Francis Ogden Medford’s thirty thousand-dollar special Mercedes Hispano Snoozer went growling down the gravel driveway. There was somebody sitting next to the Monster for a change. I got only a flash of him as the car went by, and for a moment I thought it looked like the Infant. But of course it couldn’t have been.

The golf world never heard of the kid any more. It was too bad, but it often happens that way. They zoom up out of the unknown like skyrockets, take a licking, and that’s the end of them.

So that’s why I got such a kick out of that picture in the newspaper I started telling you about. It was a photograph taken in Washington recently, and showed Brig. Gen. F.O. Medford pinning the Distinguished Flying Cross to the chest of Capt. Ted Wilson of the U. S. Army Air Force for his share in dropping steel posies on Hirohito on the occasion of that little social call the boys made over Tokyo.

The Infant was taller and older, but he seemed just the same — a fine, wonderful kid, but the Monster, as he gazed at him and the medal he had just given him, looked as though he would bust right out of his uniform with pride. You would have thought you were looking at father and son.

Well, in a way, you were. There was a yarn went with the picture. A reporter had dug up the story of how Medford and Wilson had once met for the amateur golf championship and the way the match had ended. But he had dug a little farther than that, and told how the millionaire sportsman had become interested in the boy who had given him such a close battle and in the end had practically adopted him, looking after him and sending him through college.

The boy had given up golf to further his education. When the war broke out shortly after he graduated, young Wilson enlisted in the Air Force. Medford, too, returned to active duty and rose to be a flying general.

And so the story really ended in Washington with that look of glowing pride on the face of the Monster, and the Infant standing there so straight and happy with that little bronze cross.

I couldn’t help but wonder what would have happened if I hadn’t called that ball that day. The kid would have won, and probably signed with us, and been just another pro, touring the citrus circuit in the winter for coffee and cakes. Gee, I was glad I’d been a sap and hollered. I didn’t even care any more about that two-five-oh I had to hand over to J. Sears Hammett on that dismal afternoon.

Ogden Nash on the Car as Rite of Passage

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

In this charming 1934 essay, the great American poet and humorist treats on the “in-between” generation — those who grew up while the horse and buggy was giving way to the automobile, and trusting in neither.

Psychiatrists differ among themselves as to just what is the most important step in the progress of the human male toward the complete life. They differ noisily, they differ bitterly, pausing occasionally to split the profits resulting from the argument, then resuming anew, as psychiatrists will. “The first kiss,” says Vienna. “The first shaving lotion,” says Berlin. “The first tail coat,” says London. New York holds out for the first weekly salary check, while Baltimore meekly suggests that the first approach of paternity may mean a lot.

The only conclusion to be drawn from this futile bickering is that psychiatry is not only in its infancy, as the doctors themselves admit, but lingers in the halcyon days before horseless carriages, when people could think of no better ways to pass the time than osculation, self-adornment, self-support, and matrimony. Lurking in the furthermost leather recesses of their secluded and luxurious consulting rooms, lost in morbid contemplation of the horrific and scandalous details that fill their case books, psychiatrists have failed to remark a fact now so well established as to be obvious to any mind but their own — that modern man begins to live life to the utmost only after he has driven his first car its first 1,000 miles. Take the case of Mr. Migg.

Mr. Migg belongs to the unhappy generation that was psychologically squashed between the tailboard of the buggy and the acetylene headlights of the Pope Toledo. Children born five years earlier than he, arrived with a curry comb in one hand and a bridle in the other; five years later, they wore goggles and were equipped with drivers’ licenses. To this in-between generation belongs the doubtful privilege of instinctively distrusting both the horse and the automobile.

People proud of their modernity spoke rudely of horses during Mr. Migg’s childhood; they wondered how they had ever put up with horses; their skittishness, their viciousness, their sloth, their undependability; Mr. Migg received the ineradicable impression that a horse was a combination of tapeworm, tiger, and tornado. He was definitely off horses. Once in his youth he gave a horse an apple because a girl asked him to and stood over him till he did it. He thinks it was the bravest act of his life, for he expected to lose his arm at the elbow. True, he still has his arm, but only, he is convinced, because that horse at that moment was gorged with elbows.

On the other hand, the very people who were selling their horses down the river, trading in their whips for monkey wrenches, and turning their stables into garages, planted in Mr. Migg’s mind a leeriness of automobiles which it has taken many years to uproot. The conversation of the pioneer motorist was prideful, but it reeked of disaster. It seemed to Mr. Migg that automobiles were always breaking down or blowing up. If he had to go from one place to another, he thought, give him the good old choo-choos every time.

Years passed. Automotive engineers spent thousands of sleepless nights figuring out ways to make life easier for the motorist. Finally one automotive engineer said to another automotive engineer, “I’ve got it;” and the other automotive engineer said, “What?” and the first automotive engineer said, “Let’s fix it so the motorist can motor sitting down.” Everybody thought that was a splendid idea and wondered why no one had ever thought of it before. The first step was to move the gasoline tank out from under the front seat. There was some stiff opposition to this move, as many people complained that getting out and lifting up the front seat every 10 gallons or so gave them a needed opportunity to recover hairpins, love letters, odd change, latch keys, and other small objects which they had been wondering where they were for days. Public reaction, on the whole, however, was favorable, and the automotive engineers went ahead. Lights, for example. It used to take two people to turn the lights on. One to stand twisting the jigger on the acetylene tank on the running board, and another to stand with a lighted match by the headlights. It could be done by one man, but he had to be exceptionally fast on his feet. If he took too long to cover the ground between the tank and the headlights, he was likely to be blown into the livery stable when he applied the match. This elaborate process finally struck some automotive engineer as being highly inconvenient. He was probably a slow-moving man with sore feet; at any rate, he succeeded in correcting it, and the rest of us can now turn on the lights without first stopping the car.

The designers were overcoming Mr. Migg’s prejudices one by one. When they fixed it so that you could start the engine without going out front and winding it up, he succumbed. He even speculated timidly on the possibility of some day learning to drive. It took several years for this idea to blossom, but eventually, on entering college, he borrowed his roommate’s car, somehow passed a Massachusetts driver’s test, and three hours later, turning out to avoid a truck, drove rapidly into the side of the Odd Fellows’ Hall in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. He left his roommate to cope with the Odd Fellows and took a train back to Boston.

The next time he straddled a steering rod was, as in the episode of the horse and the apple, at the instigation of a lady. She would like to go for a drive in the country, she said. Mr. Migg could think of no one who would not be better off for a drive in the country, and he said so. It was only then that he discovered that the lady did not drive. She could, she said, get her brother to drive, if Mr. Migg wouldn’t mind sitting in the backseat. Mr. Migg said he loved driving. They set off in a stream of traffic that failed to diminish as they left the city limits behind. Nevertheless, all went swimmingly till, halfway up a steep hill, the lady decided that she liked the looks of a little road leading off to the left. Chivalrous as always, Mr. Migg stuck out his hand, racked the gears to shreds, stalled the motor, and coasted backwards to the foot of the hill through a shrieking maze of infuriated 10-ton trucks. “I guess you’re not used to this car,” she said kindly. Mr. Migg agreed, and started up the hill again. After a few more failed attempts, she said she thought she remembered hearing that there were bandits or wild dogs or something along that road to the left and she’d just as soon go straight home.

He passed the next few years pleasantly in qualifying for a driver’s license in New York State. He finally obtained it, and almost immediately found himself the head of a family three states away. Cause and result? Mr. Migg hesitates to say. He only knows that he found that he and his wife would have to get a car, and get one immediate.

Once having bought his own car, he could think of nothing else but getting those first 1,000 miles under his belt. Mr. Migg begs for errands to drive. He drives to the mail box and the drug store and the grocery store, none of them farther distant from the house than a clean three-base hit, and he wishes he could drive from the living room into the dining room. When you’re trying to cover 1,000 miles at 27 miles an hour every inch counts. If the Miggs have the choice of several movies, they go not to the best but to the farthest. Old ladies far out in the country whom they haven’t seen in years are being surprised every day by little visits from the Miggs. They never lose a chance to take people home from parties, particularly if they live well out of the way. They are getting quite a reputation for being friendly and obliging.

Mr. Migg still winces when he has to pull over to let a homemade sports roadster go by. But he checked the mileage this morning. Only 57 more to go. Only 57 miles from manhood. He notices that the speedometer registers up to 95.

—“The First Thousand Miles,”

The Saturday Evening Post, February 24, 1934

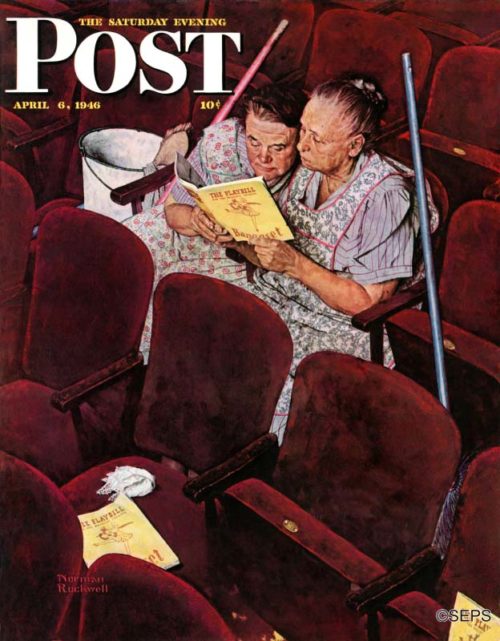

Master of the Seascape Christopher Blossom

Christopher Blossom has dreamed of tall wooden ships his whole life.

Enchanted by their mystique, he has watched the great vessels wend in and out of ports near his home in coastal Connecticut. He’s studied the lore of cutters, frigates, men-of-war, schooners, and other craft, and he’s brought their dramatic stories to life. A sailor for nearly as long as he can remember, Blossom grew up, too, around legendary people considered the tall ships of their own time — illustrators who painted the visual narratives of American life and history for the popular magazines of their day.

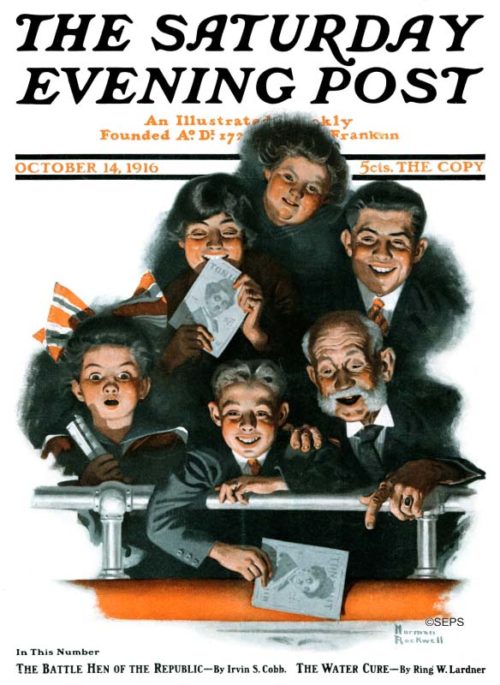

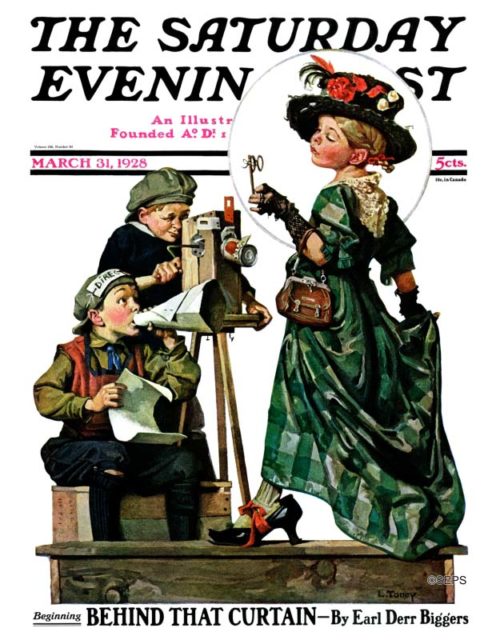

For Blossom, counted today among the greatest marine artists of his generation, those esteemed illustrators included his own late father, David Blossom, grandad Earl Blossom, and a broad circle of friends whose resonant work resides in museums and prominent personal collections. “Landing assignments with The Saturday Evening Post was considered the most prestigious, and winning the cover was a huge achievement,” Blossom says. “When I was young, I didn’t realize just how big it was for people of my father’s and grandfather’s eras. So many of my friends were the children of great illustrators, and when their parents’ work appeared in the popular magazines you saw at newsstands, you didn’t think about the fact that millions of people were seeing those pictures around the world.”

No one is more familiar with Blossom’s legacy than J. Russell Jinishian, owner of an eponymous art gallery in Fairfield, Connecticut, that represents the biggest names in contemporary marine and sporting art. Jinishian authored a book, Bound for Blue Water: Contemporary American Marine Art, that chronicles the best painters of the last 50 years. He puts Blossom at the very top.

“You have to understand that Chris is part of a very unusual lineage. The sons and daughters of most reputable artists tend to become anything but artists. Chris is third-generation, and his work sets the standard,” Jinishian says. “I liken the Blossoms to the Wyeth family [N.C., Andrew, and Jamie] in terms of talent and dedication to craft. I can’t think of anyone else in a third-generation art family who has risen to the top of the field, as Chris has, in both marine art and as a plein-air painter.”

Blossom’s portrayals of near-mythic ships have earned him favorable comparisons to master marine painters John Stobart and Montague Dawson. A prime example of Blossom’s talent is a piece titled U.S. Brig Porpoise Transiting Deception Pass, June 1841. It portrays the good ship Porpoise finding its way through coastal waters around the San Juan Islands near Seattle, a course purported to be perilous and unnavigable. Blossom puts the viewer into a fateful scene that proved the premise wrong.

Striking is the calming tranquility of the painting, summoning emotions in the viewer driven as much by the effect of color and light as by the setting and subject. Indeed, Blossom uses narratives to pique our attention, but it is his command of his medium that cements a sensual connection. His paintings read visually as places we somehow recognize in our minds’ eyes. “What I am trying to paint is a particular kind of atmosphere and mood that comes through in the way you present light,” he says, noting that it might be a sanguine sunset or a storm with high seas and muted illumination. “Mood is everything. It doesn’t matter where or when in terms of an exact place. The sensation you feel is universal, and that’s what gives it veracity.” This is also why, critics say, Blossom’s paintings evince a sense of timelessness.

Born in 1956, Blossom, perhaps surprisingly, had no inclination to paint during his early teenage years. His passion was sailing. Still, as a youngster, he posed in costumes for paintings made by illustration icons, including Harold von Schmidt, a noted Post illustrator who then was in the final years of his life. “Von Schmidt would have these big Western-style barbecues every Fourth of July upstate in Connecticut,” remembers Blossom, “and many great illustrators and their families would go there to eat and shoot off fireworks.”

Von Schmidt died in Westport, Connecticut, in 1982. During his prime, he was a contemporary of Norman Rockwell and John Clymer. And he had solid friendships with N.C. Wyeth, Harvey Dunn, and Dean Cornwell, prized students of Howard Pyle, considered the godfather of the Golden Age of Illustration. Many of Pyle’s protégés had pieces published in the Post.

Blossom’s grandfather Earl (1891–1970) had joined the Post’s stable of go-to illustrators when Pete Martin, whom he had known in Chicago, was named the magazine’s art director. Under tight deadlines, Earl Blossom delivered paintings that illustrated fictional potboilers, a Post hallmark. Later, Earl Blossom became a star with Collier’s, and its art director there once told a reporter, “He’s a masterful artist. You never have to tell him what to do.”

Such creativity was passed down through the Blossom clan. Chris Blossom’s dad, David (1927–1995), also completed illustrations for the Post, though he is most recognized perhaps for his movie posters, especially those featuring Clint Eastwood in the Sergio Leone “spaghetti Westerns” The Good, The Bad and the Ugly; A Fistful of Dollars; and For a Few Dollars More. He also did a tremendous number of book covers and was known for doing Outdoor Life covers.

Young Chris and his brothers, David and Peter, got to know illustrators like Paul Calle, Clymer, Tom Lovell, and others who literally lived next door. Next to Rockwell, Clymer was one of the most prolific Post cover artists ever, and later, in the late 1980s after he had resettled in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, he told me that he considered Blossom a promising talent to watch.

Although Blossom was raised with his father constantly working behind the easel, the idea of making painting a career didn’t readily enter his mind until he was nearly out of high school. When Blossom did start to draw and paint, the combination of innate talent and insight absorbed through exposure to the giants of pictorial painting turned him into something of a wunderkind. He was a student at the Parsons School of Design. At age 20, he won a scholarship in a national competition sponsored by the Society of Illustrators.

Blossom’s father had earlier introduced his son to maritime painter John Stobart, a transplant from England, and they became friends. It was not uncommon for them to stop by Stobart’s studio and see what vivid paintings he was working on.

During those impressionable years, Blossom became influenced by Impressionist painters John Singer Sargent, Joaquín Sorolla, Anders Zorn, and Russian Isaak Levitan. Famously, Levitan once observed, “What can be more tragic than to feel the boundlessness of the surrounding beauty and to be able to see in it its underlying mystery … and yet to be aware of your own inability to express these large feelings.”

Blossom’s work does not stand accused of suffering from repressed passion or an inability to make visible the unseen, though his play on the past is not sentimental or cheaply nostalgic.

For a time out of college, Blossom worked as a commercial illustrator, and the toils of having to work quickly, distilling the essence of subjects down to engaging visual statements, became a training ground just as it had for the Blossom elders.

For those who dismiss painters with a commercial illustration background as second-tier, Jinishian notes, “Michelangelo was an illustrator, and he invented, out of thin air, the scenes we equate with being the highest form of art. One of the criticisms people have used over time to try and diminish the talent of the great illustrators who worked for the Post and other magazines is the argument that, because they didn’t actually witness the scenes they painted, it was conjuring. But guess what: As far as anyone knows, Michelangelo never saw the moment of creation that he depicted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Nobody ever said, ‘Mike, that’s a made-up thing you’re painting.’”

Some of Blossom’s paintings carry an intensity reflected in the stormy ocean conditions being portrayed, where textured effulgent waves are rising and falling, putting water over the gunwales. You can almost see the wind being tacked. Maybe the only things missing are an actual spray of sea salt blown into the viewer’s eyes, the briny smell of the cold Pacific, and the taste of ocean air on the tongue.

A decade ago, Blossom and his wife took a year off and sailed up and down the Eastern seaboard from Maine to the Bahamas and back. He produced a stack of plein-air paintings along the way and returned to his studio refreshed. “The power of nature is pretty awesome,” he says. “To assume that you can push the limits of risk and never get caught is a fallacy.”

Skippering boats on the open sea is exhilarating for Blossom because there’s a very small safety net, set within the overwhelming forces of nature. “The thing I find most interesting about cruising is the exhilaration of exploring and the self-sufficiency which requires that you troubleshoot problems, think things through, and adapt. Yes, we have better weather information, but you’re still on your own. You are independent and isolated in the way that an astronaut might be.”

It’s a metaphor, he notes, that can also be applied to painting. After years of winning other honors, his greatest achievement to date came in 2010, when he won the top prize at the Prix de West Exhibition in Oklahoma City for his painting Sunrise in the Golden Gate; Downeaster Benjamin F. Packard.

At Prix de West, across a span of years, Blossom prestigiously has received the coveted Robert Lougheed Award four times. The accolade is bestowed by fellow artists for best grouping of three or more paintings. (Lougheed was another illustrator who, early in his career, contributed to the Post before becoming a figure in Western art.)

While some say winning Prix de West marked Blossom’s formal arrival in the pantheon of contemporary Western artists, friends like painter Jim Morgan say it only confirms a talent that he has demonstrated for years in his forays across the inner continent of North America and Europe. Blossom is, by his own admission, a modern Romantic Realist.

Morgan himself is a widely respected oil painter known for his portrayals of wildlife and landscapes, most often Western scenes terrestrial, the influence of the Pacific overlooked. Far from the dust of a rodeo ring, Indian pueblo, or vaulting jawlines of the Rockies, this vision, too, is an important visual aspect of the American West. The nautical tradition encompasses galleons of Spanish conquistadors, exploratory British flagships, cutters carrying Asian laborers to build the transcontinental railroad, and vessels ferrying gold miners north to the Klondike à la Jack London.

Blossom may be only an itinerant Westerner, but he has tens of thousands of miles and hours under his belt in the red rock deserts, inner mountain ranges, and Pacific coastline. He has also spent countless hours prowling the Atlantic, but he does not compartmentalize one from the other. “In fact, I view my maritime work as landscape with water and vessels,” Blossom says.

“Chris’ wonderfully unique marine paintings are as much a portal into the development of the American West as a Moran, Russell, or Remington, but from the perspective of the sea,” Morgan explains. “There seems to be a deep gene pool of imaginative, deliberate, thoughtful, no-accident fine art. The creative apple seems not to have fallen far from the family tree. Chris is continuing the fine tradition of great artists.”

A Utahan, Morgan has reverence for Blossom’s ties to the grand illustration heritage of the East. He has joined Blossom on treks, via horseback, into the Western wilderness. “Chris is solidly on the creative high ground of great representational art being done today. He has few peers anywhere,” Morgan says. “No matter if the inspiration for painting is a red rock desert canyon or the high seas, it is undoubtedly of the highest quality. Subject matter aside, Chris’ art has no boundaries.”

Scott Usher, the CEO of Greenwich Workshop, which has made available a number of Blossom paintings as limited-edition prints, credits the artist’s tenacity and instinct with consistently producing head-turning work, but he notes that on top of it, “there’s this 15 percent factor of pure magic.”

Blossom ponders aloud what intrigues him about the Rocky Mountains. “Conveying distance is something that has always intrigued me. Out on the ocean, you deal with a lot of distance, but there is no scale to put it in perspective. Out west, you can see for 100 miles. Color is brilliant because the air is clear and not humid or hazy. For me, it was eye-opening, and communicating it a challenge.”

What does Blossom prefer — the mighty Atlantic or spying peaks that rise a mile and a half above sea level? “The mountains are far more impressive. Ships make for fascinating subjects, but they are beautiful things humans have created. Mountains are elemental and have a monumentality, a sense and a presence that can’t be re-created with our hands. As artists, we can only try to catch a sense of them,” Blossom says. “I understand why so many illustrators, as their profession started to die with the advent of the camera, headed west.”

“The thing that distinguishes his work, and makes it interesting, is that he’s always looking for new and unusual approaches to presenting his subjects. He could make a lot of money painting a popular setting over and over again — which some artists do — but that’s not the way he is wired,” Jinishian says. “The simple fact is that he has a way of seeing the world that is different from other artists. His art is the way he processes the world, and his paintings are like he is, loaded with creative intelligence, but very lean, with no fat.”

An exemplar of Blossom’s authenticity is Pilot Boat Mary Taylor Off Sandy Hook 1849, which celebrates a boat designed by the same shipbuilder who constructed the racing yacht America, first winner of the America’s Cup sailing trophy in 1851. Another painting, Loading Lumber in Port Blakely, portrays a seaside town in Washington State that, in the 1870s, was home to one of the largest sawmills in the country. Using floating log booms as design elements, he delivers a mesmerizing composition that is also a reference point for pondering history.

“I covet his paintings as very subtle things of singular beauty,” Jinishian says. “For him to end up on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post just has a rightness about it.”

As Blossom demonstrates in his scenes, what’s old can brandish relevance anew as we sail off into his sunsets. Just as Blossom has returned to his roots of illustration for inspiration, so, too, does the Post.

Todd Wilkinson has been writing about art, nature, and the West for nearly 30 years. His last story for the Post was on Western artist Howard Terpning for the Sept/Oct 2015 issue. His most recent book is Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek: An Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Bear of Greater Yellowstone, with photographs by Thomas D. Mangelsen.

This article is featured in the March/April 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

A Quick Guide to Impeachment

February 24 is the anniversary of President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment in 1868. Many Americans are more familiar with Bill Clinton’s impeachment than with Johnson’s, but our un-scientific survey revealed that even well-informed people are a little fuzzy on what impeachment actually is and how it works, exactly. Here’s a quick overview:

What Is Impeachment?

Impeachment means indictment — specifically, a charge of serious misconduct against a high official by a legislature. Article II of the Constitution says the president, vice president, and “civil officers of the United States” can be impeached. Whether or not members of Congress are included in “civil officers” is still debated.

Two presidents have been impeached, but neither were convicted.

What Exactly Is an Impeachable Offense?

The Constitution defines impeachable offenses as “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” But these are broad, debatable terms.

Constitutional lawyers define “high crimes and misdemeanors” as anything that breaks existing law, is an abuse of power, or, as Alexander Hamilton wrote, is “the abuse or violation of some public trust.”

Gerald R. Ford gave a working definition of an impeachable offense: “whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment.”

In practice, articles of impeachment have cited acts that exceed the constitutional limits of the powers of an office, behavior at odds with the function and purpose of an office, or use of an office for improper purposes or personal gain.

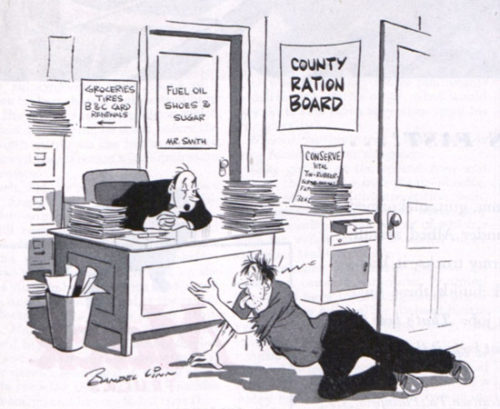

How Does the Impeachment Process Work?

The House Indicts

The House of Representatives begins the impeachment process. The House Judiciary Committee starts the process by sending to the House articles of impeachment, a resolution that spells out why impeachment is justified. The House then debates and votes on that resolution. An official is impeached only if two-thirds of the House approves the articles of impeachment. But the House can’t take action beyond this vote, and the impeached official isn’t removed from office.

The Senate Convicts and Expels

The impeached official now faces a trial in the Senate. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court acts as judge in the proceedings, and the Senators are the jury. After hearing the evidence, the Senators meet privately and discuss their verdict. If two-thirds of the Senators agree, the impeached official will be convicted and removed from office. The Senate may even pass a resolution forbidding the official from ever again holding public office.

Who Has Been Impeached?

- Moves toward impeachment were made against John Tyler (1841-1845) when Congress resented his use of the presidential veto, but the resolution against him failed.

- Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) was impeached for his lenient attitude toward the defeated Confederate states, which allowed many of its pre-war officials to return to office. The triggering event was his dismissal of Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s Secretary of War, who opposed Johnson’s policies. Johnson was impeached by the House, tried in the Senate, and acquitted by a single vote.

- Congress was debating the impeachment of Richard Nixon (1969-1974) over the Watergate scandal when he resigned.

- Bill Clinton (1993-2001) was charged in 1998 with perjury and obstruction of justice in the investigation of his affair with a White House intern. He was impeached by the House but acquitted by the Senate.

Extra Credit: The First Impeachment Hearings

Americans are naturally troubled by the prospect of a presidential impeachment. In March 1868, when President Andrew Johnson was being impeached, the Post reassured readers that impeachment was a necessary, vital part of our democratic process. It contrasted, perhaps unfairly, the orderly process of trying the U.S. president to the armed turmoil shaking the governments of Mexico and Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic). But it expressed ultimate faith in the American people and their Constitution.

Not Mexico

For a short period dining the first excitement of the Impeachment, we began to doubt whether we were living in the United States or in Mexico — but the sober second thought of the people soon rectified the blunders of foolish partisans.

The House of Representatives has an undoubted right to impeach the President, or the Acting President, whichever his true position may be. Its members have the right to judge for themselves of the propriety of their course.

The Senate has the undoubted right — nay more it is its duty — to sit in judgment on the charges that are brought by the House — and acquit, or find guilty, as a majority of two-thirds sees proper. If the Senate finds President Johnson guilty of high crimes and misdemeanors, he must, and doubtless will, without any hesitation, conform to that judgment.

It may be said, that both House and Senate may act in the spirit of mere partisans, and alike accuse and condemn without sufficient evidence. Undoubtedly they may. But the Constitution supposes that they will not. If they do act as mere partisans, their punishment will be the rebuke of the people.

In the Autumn, the Republican party goes before the People — with its candidate for the Presidency, its candidates for Congress. The fair or unfair manner in which the Impeachment trial has been conducted, will be an important element in the canvass. In fact, the Impeachers themselves will be then put on their trial, before the great Jury of the People of the United States.

And thus there is no need of soldiers and bayonets — no need to make these United States a Mexico or St. Domingo. Ultimately all these vexed questions must be decided by the people. Ultimately the will of the people will prevail. Both the contending parties profess to desire this. Let all then be done peaceably, legally, and in order. It will be no recommendation to either party, in the great Presidential and Congressional campaign of the coming Autumn, that it has needlessly broken the peace, and plunged the Union into civil strife.

Editorial, March 7, 1868

Featured image: Impeachment ticket for President Johnson (U.S. Senate)

Open Times

Blake reaches in his pocket and fingers a blue rubber band, the thick sort with resistance. He can already see the expectant faces, hopeful faces waiting for answers to impossible questions. How do you cope with stress? Do you ever lose control? He spreads his fingers.

It’s early, just before he needs to make rounds, and he attempts a few guiding notes, some lyrical words. He browses through online databases looking for quotes that aren’t completely misguided. He writes.

My scalpel is a telephone, a way of communicating with another human being. No. My blade is a paintbrush. It’s a light, a tiny flashlight. No. My work is to navigate the map of the human body, to reveal stories that are buried beneath the skin. No.

Blake circles the words map and buried before noticing a couple standing a few feet away. Public displays of affection are tolerable some days. Not today. Today, purple clouds are closing in around them, the only three in the park so early in the morning, settled near the basketball courts. He crosses out paintbrush because the line seems too pretentious and shifts on the hard bench as thunder rolls above. The storm charges forward.

Blake closes his notebook — those precious few words contained. Writing a presentation for third-year med students, something that will inspire some and scare off those who should be saved before they’re too far in debt, is a real pain. He never imagined he’d ever have to return to the horrendous lecture halls he’d barely survived.

The couple kisses with sloppy tongues, showing off their youth, as the rain begins. With less than two hours before he needs to deliver his speech, Blake nestles the notebook in his bag and makes his way to his new, custom-built BMW 230i convertible. It’s the kind of car a younger version of himself could never imagine owning. It’s a car he can barely imagine himself owning now. Every time he walks toward it, there is the feeling that he’s won something, game-show style, and he can’t help but swagger.

His stomach revs with the engine. His machine glides through the storm. It pauses in front of Scarlet Café, which is closed, and then Blue Coffee, which is also closed. Blake is an OSU grad, hardly a Michigan fan, but the service at Blue is better.

He idles for a few minutes, peering in the windows to make out a scrawny guy, who he thinks manages the place, refilling straws. Blake wonders if he has time to wait. It’s an 8-minute drive to work, and his first appointment is in 15. He could get there in 7, but he’s cutting it close as it is, waiting for inspiration to come.

No café is open until 5:30 a.m., even though this is the med center, a part of town populated by doctors who are crepuscular animals known for their staggering caffeine dependence.

With no immediate access to decent coffee, he moves a block down and stops at the gas station, jogs toward the small shop without umbrella, and watches, disdainfully, as the off-brand coffee percolates. “One minute,” the gas station attendant says with a smile. Blake has one minute. Not much more.

He hovers around a warming oven filled with donuts, watches the icing dripping from thin metal racks, and eyes the rows of lottery tickets across the aisle. There is a cluster of women, three of them, buying scratch-offs, scratching them with quarters, then buying more or cashing in for a few bucks. They look related, these three. They look as though they inhabit a different planet, all loud pastels against a backdrop of gray.

Blake watches one of the three, a middle-aged woman in ripped jeans with a touch of jaundice, lift her arms like a superhero. She squeals, “Forty dollars, forty dollars, ya’ll!” Her friends check the ticket, recheck their own tickets, and congratulate her without any apparent sincerity. The woman turns to Blake. “You! You’re my lucky charm. I won right when you passed. Bless you. Bless you. Can I buy your coffee? Will you walk by again, just like that while I scratch this last one?”

“No worries,” he says, smiling but not moving.

“I see. Well, can you stand there awhile, while I scratch off a few more?”

The coffee is ready. Blake can make out the grounds floating on the top of murky liquid. He glances at his smartwatch. “One more, then I have to go.” There is a short bottle of liquid next to him that promises a cornucopia of vitamins, along with a healthy dose of caffeine. It appears to be marketed as a panacea, with so many promises listed on the label that there is no room for readable text. He places it, along with a pack of gum fortified with Vitamin B2, on the counter.

“You a doctor?” the youngest of the women asks as he unrolls a few dollars from his money clip to pay. Her ball cap is bejeweled and spells out U.S.A.

“Have a good day, ladies,” he says, leaving them to tease out the mystery. His phone vibrates. He rushes out without getting his change, hearing another yelp of joy as he walks out and wondering what kind of jackpot was achieved.

Blake’s machine is efficient on wet roads, far more so than the Jeep he used to drive when he was still paying off loans. The tires do their work, angling and gripping and getting him to the dozen-decker parking lot without so much as a slip or skid. He takes one of the first reserved spots. Glancing in the rearview, he sees the gray in his beard. He downs the syrupy contents of the small bottle and scrambles to open the driver’s side door in enough time to spit it out. He jogs toward his office to collect his thoughts, his mouth watering around the acerbic remnants of the toxic energy drink.

The hospital café isn’t open till 8 a.m., and he has only a few minutes to sign in. He must check on two patients, then deliver his speech. The idea hits him that there should be drones delivering quality coffee to doctors at the press of a button, and he jots this note down. 5:30 a.m. exactly, and as he strides down the linoleum halls, he calls Blue Coffee, requesting a special delivery. He’ll order coffee for the whole floor so it doesn’t look so self-indulgent. He assures he’ll tip well.

As he waits, he finds a French press and searches his office for some leftover grounds. Nothing. Ani, one of his favorite baristas and usually the cashier at Blue Coffee, says she’ll check with her boss but will try to make it happen.

“So long as you can get me that coffee before 7 a.m. I have a speech to deliver,” he explains, angling the phone on his shoulder as he checks the break room, only to find some instant coffee — hardly enough for a cup.

After the third hold song, Ani returns. “I got it approved,” she says. “I’ll be there in a jiff.”

From Room 8A, Blake and his patient watch the rain as they go down a series of follow-up questions. Mr. Heller explains that he is in a lot of pain and would kindly like some Xanax. Blake assures him that the pain is temporary, and that the incision appears fine. “It’s healing just fine,” he says, assuredly, then offers a smile-nod combo that he tends to offer when refusing Xanax. He tells Mr. Heller to watch the rain a moment. “How’s your breathing?” he asks. “Really pay attention.”

A fill-in nurse, someone named Trudy, concurs. Mr. Heller breathes. He breathes slower, watches the rain, and, finally, closes his eyes.

“No one else can do that,” the nurse whispers on their way out. Blake worries she’s right.

The thing about Blake is, he knows how to focus — no matter caffeine withdrawal or whatever else. But as soon as he’s out of 8A, he’s wondering where Ani is. He checks his watch. Only 7,034 steps. Did he give her clear enough instructions? Does she have the common sense to take one of the good, RESERVED spots in the lot as opposed to walking a damn block from the visitors’ area?

Patient No. 2 is not an easy one. Mrs. Sebastian Willow, who insists being referred to as such, is what lesser doctors refer to as a frequent flyer. This is her third carpal surgery, second wrist. Blake counts backwards from 100 as he suits up. He’s filling in for yet another new surgeon who didn’t sign up on his round.

The precision of an endoscopic surgery for carpal on a woman with the tiniest wrists he’s seen in his lifetime is not something he’d been looking forward to, but it is something he will execute with precision and grace. Five, four, three, two … one. He enters the room to meet with two assistants and his station set up to perfection. The tiny tools that were once fumbled and dropped with his clumsy, big hands, are now a part of him, an 11th finger or a mechanical extension. He cuts away the flesh and navigates around the thin line to avoid nerve damage. He feels the pressure release, subtle, or thinks he does, as he places tiny incisions. This woman will be back to texting in a few hours.

Ms. Sebastian Willow will be checked out as soon as her paperwork is complete, Blake explains. He provides her with aftercare instructions and tells her to stay off Facebook for a while.

“Instagram okay?”

The coffee should be here. Blake made good time. He has almost 20 minutes to spare before his presentation and, still with no idea what to say, he figures he could give an account of the very surgery he just completed. Perhaps he could frame an entire speech around a surgery. His head screams at him, somewhere along the forehead just above the eyebrows. It screams out in withdrawal.

Speed-walking to the front desk, Blake glances down at his watch to see 11,000 steps. Most people are just waking up. He asks if someone has been around to deliver coffee, and Anita, the receptionist with phenomenally big hair and watery eyes, says no.

Blake’s headache seems to be wrapping around his head, scarf-like, now. He rushes down the hall, toward the parking lot, wondering if he could make it back to the gas station in time to return for his speech. He recalls the anxiety attacks he used to have in front of groups, the terror of being unprepared. He imagines himself in the audience of students, bored and eager all at the same, waiting to be a doctor. He remembers the invincibility of promise, endless promise. He tells Anita to wish him luck.

“Sweetie,” she says, with a maternal sweetness. “You got this, whatever it is.”

He lets out a breathy laugh as Ani, resplendent Ani, arrives with a tray full off coffee and one single small cup that promises to hold a quad espresso just for him. He wants to tip her $100. He reaches out his arms in joy as though ready to hug her as she sets the tray down on the counter.

He pulls out a $50 and hands it to her, which he thinks will leave her $10 for the trip. She smiles and turns on a heel, waving goodbye and explaining that she wants to beat the storm on the way back.

“Thank you,” he calls out. He sees she drops something, the cash! And he calls out, gesturing quickly to get her attention before she is out of earshot. Just as she turns, his hand gestures down. The tiny cup, the glorious one, falls to the ground. The small plastic lid bounces off and lands beneath a chair. The golden-brown liquid turns to a small puddle near Blake’s feet.

As the puddle spreads, a woman in a wheelchair screams out in pain. There is an emergency laparoscopic call to action. Blake counts backwards from 100. He realizes he’s the only one on-call right now and will have to meet with the students late.

The life of a surgeon, he’ll say, is such that you cannot over-prepare. Now is the only time you’ll have. Take advantage of it. The things, the lifestyle, the fancy car you may be able to afford, are all simply ways to get you back to the core, this hospital, where you will live to save others from pain.

Blake stands in front of over 100 med students and recounts his morning. “I’ve hit 21,000 steps since 4 a.m., I’d really like a cup of coffee, and I’ve met with three patients, executing two surgeries, one of which was an emergency.” He goes on. He examines their eyes, pulling a small rubber band out of his pocket. “I count down from 100 whenever I need to find my center. I stretch this small rubber band with each count.”

Four students drop out that week. Blake receives a single note, which Anita delivers with a smile. “It has a gift card in it, I think!”

When Blake opens it, he is in his office. It’s a Friday, and he’s fully caffeinated. It is a thank-you note from a student who says she is third year. The small plastic card containing a mantra: “Go on,” and the handwritten note, resplendent in barely readable doctor scrawl, simply says, “I carry a rubber band now. I’m ready.”

“Sure are,” Blake says. He reaches in his pocket, stretches the band, and takes a breath. The clock, such an archaic and beautiful thing, ticks, and he thinks about how precise the gears must fit to balance time. He looks down at his smartwatch and sees 28,439 steps. He writes the number down in a small notebook before standing to stretch, walking slowly toward his perfect car. He heads home to a quiet apartment, where he will sit with a novel, pausing now and again to acknowledge the hope he feels for the world.

News of the Week: Presidents, Pluto, and the Perfect Snacks for Oscar Night

And the Greatest President of All Time Is…

… Millard Fillmore! That’s right, according to a new survey that ranks our nation’s leaders over the years, the greatest president of all time is Millard Fillmore.

Okay, I’m lying (or maybe I’m just providing “alternative facts”). C-SPAN conducted a Presidential Historians Survey to rank the U.S. presidents. It’s probably not a surprise that Abraham Lincoln tops the list, followed by George Washington and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. But what about John F. Kennedy placing above Ronald Reagan? Or Barack Obama placing 12th even though he just left office?

William Henry Harrison isn’t last, even though he was only in office for 31 days. (He didn’t listen to his mom when she told him to wear a coat at the inauguration and died from pneumonia.) This is one of those surveys that’s built for an argument.

We once had a president named Chester Arthur. I always forget that.

NASA Wants to Make Pluto a Planet Again

Poor Pluto. One day you’re a planet, the next you’re not. But it’s another day, and maybe you’re going to be one once again.