Originally published on February 2, 1935

Originally published on February 2, 1935

No one in our town had ever known such a wholly devoted mother as Mrs. Estes was. “Maybe it’s only natural,” Mrs. Rogers said uneasily. “When you think she’s buried five. But my land, she don’t have a thought in her head but Lois. She just lives and breathes in that child.”

My mother didn’t glance at me, but her reply did. “Well, such a sweet, good, obedient little thing. Anybody’d be thankful to have a little girl like Lois you didn’t have to nag at the livelong time to make ‘em behave.”

Mrs. Rogers agreed: “If ever there was a little angel on earth — and those curls, just like sunshine.”

The worst of it was that we could not take it out on Lois. She was a constant good example, but somehow we could not wholeheartedly detest her. Her goodness did not seem to be quite her fault. She was good as if she couldn’t help it. “Mama says I mustn’t,” she’d almost whimper.

“All right for you, fraidy cat!” we’d answer, leaving her. It must be said that she was no tattletale. Of course, she was never questioned; no one could suspect her of even knowing about our naughtiness. Quite often she didn’t. She was a rather lonely little girl.

Mrs. Estes lived in a tiny unpainted house on the back street, behind the Shermans’ barn. Of course Mr. Estes lived there, too, but he was a little man with walrus mustaches, always answering advertisements which promised a live hustler as much as $10.86 a week. We connected him vaguely with books, perfumes, complexion soaps — things no sensible woman would spend good money for. Once he frightened us with the notion of burning gasoline in a lamp; it was a mercy the thing didn’t explode and burn everybody out of house and home. Then he tried to sell mats of a new thing called asbestos. He said fire wouldn’t burn them.

“Mercy, what next?” my mother said. “How Mrs. Estes ever puts up with it all — and she trying to hold up her head with the best, the way she does.”

“They won’t burn, for a fact,” said my father. “Most the men in the barber shop bet money on it. Jay Willard put up a dollar bill. So we all went across to the blacksmith shop and got Murphy to blow up his fire full blast, but to save our necks we couldn’t make the dang thing — ”

“Joe Allen!” my mother interrupted. “You mean to tell me you bet good mon — ”

“I am not telling you any such a thing!” my father almost shouted. “You want to know what goes on uptown, or don’t you?”

“Go on,” she said coldly.

“That’s all,” said my father.

We ate in silence, till at last she said, “So it wouldn’t burn.”

“You said yourself it would,” he accused her. “And it did turn brown and start smoking. We — that is, Jay let out a yell you could hear from here to breakfast and begun joshing Estes, when dummed if the dang thing didn’t turn white again.”

“You might as well swear outright as use such language,” said my mother.

He went on: “Estes was all set up, pleased as Punch and grinning like a Chessy cat. Said he finally got hold of the right thing, this time. He sold Jim Miller a mat right there, ten cents apiece, and you can boil potatoes plumb dry on it; Estes guarantees they won’t so much as scorch.”

“Let me catch you squandering ten cents for one,” my mother said ominously. “When did I burn potatoes? If that Estes comes around insinuating I let my cooking burn, he’ll get short shrift, I promise him! Even if it would keep anything from burning; a trick of some kind’s what it is. And ten cents don’t grow on bushes. Not for me they don’t,” she added, rubbing that bet in on my father.

I don’t remember what Mr. Estes died of, nor exactly when. His death was as vague as his life. Mrs. Estes did not put Lois in black; she herself had never got out of mourning for her children in heaven, and she could not afford widow’s weeds. We had always thought of the house as her house; no doubt Mr. Estes would have lived on the south side of the tracks but for her.

How she made both ends meet no one quite knew. Women who sank to taking in washing must have earned more money than she earned by dressmaking. But Mrs. Estes was determined to keep a social position for Lois.

It was true that she lived only for Lois. As Mrs. Miniver said, that woman didn’t seem to have a selfish bone in her body. My mother suspected that she scrimped herself even on food, to keep the child looking like a little doll.

“Our lives are past,” she said once to my mother, who accepted the statement as if it didn’t taste good. “I never had anything I wanted, and I never will, but Lois is going to. If I work my fingers to the bone, she’s not going to go without.”

She was a gaunt woman with a sallow complexion and mud-colored eyes set deep against a big nose. Even as a girl she couldn’t have been pretty; likely Mr. Estes was the best she could get. They had been country folks, and at least he had ambition enough to move to town, though in the upshot she hadn’t bettered herself much. It must have been a consolation to her to have the prettiest little girl in town.

It is hard to say why I felt in Mrs. Estes a kind of tigerish hunger. She was always a lady; I never saw her make a brusque gesture or heard her voice raised. She slept in her corsets to keep her straight, inflexible figure, and at dawn she incased herself in starched calico with a tall collar. Her nondescript hair was always smooth. Nothing less tigerish can be imagined than Mrs. Estes, swiftly making buttonholes or whaleboning a bodice, her skirts concealing feet planted on the thin clean rag carpet of her front room, and her mouth shut neatly. Lois and I would glance at each other with diffidence. Mrs. Estes was an even heavier constraint than one’s own mother.

“Well, I must go now,” I’d blurt. “I only came to bring the pickle receipt, mama said I had to.”

Mrs. Estes’ look at Lois made me uncomfortable. It was a pouring-out look, as if all of Mrs. Estes came out of her eyes and ate up the delicate little face, the golden curls topped by a blue bow, the big brown eyes and fringing lashes, even the pretty dress, the unwrinkled stockings and the shoes with not one button missing.

“Say goodbye to Ernestine, nicely now.” Her voice was like a mother cat’s loud purr, licking her kitten. And that look would follow Lois. None of us had such pretty manners. A crinkle went over me. It was somehow as if Lois really were a doll — one of those figures held on a ventriloquist’s knee and speaking unnaturally with the voices he put into them. They seemed somehow wrong inside, too, so that I didn’t like to hear them and was uncomfortable without knowing why. Lois would murmur, “Goodbye, Ernestine. I am glad you called. Come again.”

I would be glad to get away. And for no reason, while I wandered homeward, rattling a stick along the Shermans’ picket fence and dragging one foot after the other, I’d chant, “I don’t care; I do as I please, I do as I please, I do as I — ”

My mother’s voice would stop that: “Ernestine! Stop that caterwauling this minute! Shame on you! And how often must I tell you to stop scuffing out your shoes as if we’re made of money? My land, I don’t know what gets into you!”

Days were limitless then; summer was summer forever, and each year’s end was too far away to be seen from that year’s beginning. When did we leave childhood’s eternity, when did space begin to close upon us and time begin to hurry us toward the end too clearly known?

There was no moment when we might have felt a pang of hesitation. Yet it seems to me now that quite suddenly we were young ladies. Our battle was for recognition. “My goodness, mama, I’m not a child! I’m going on sixteen, and I can’t wear skirts way up to my ankles! I’d just die, I’d look such a freak. Elsie’s mother’s putting her in long skirts. It won’t take but a yard more of goods, mama, please. Please, mama!”

Elsie Miller not only wore the longest skirts; she put up her hair with rhinestone combs and barrette. The rest of us had to fold our braids on the neck, under a black ribbon bow. But out of sight of our mothers, with surreptitious hairpins we pinned those braids up on our heads. Only Lois still wore dangling curls, a rich mass now almost reaching her waist. Every morning Mrs. Estes brushed each of those curls around her finger until it was a shining, perfect tube. We thought they were babyish. But we did not ask Lois why she didn’t make her mother let her stop wearing them.

It was not that we ignored her, as we ignored poor girls from south of the tracks. She was with us in school and in Sunday school; she was always invited to parties, and came, beautifully dressed and with beautiful manners. At Easter she was chosen for the tableau, Rock of Ages. Clinging to a gilded cross, her golden hair rippling down a long white robe, her gaze fixed faithfully on Heaven above the rain spot on the church ceiling, and green cheesecloth waves agitated beneath her, while Mr. Sherman, choking, held the hot shovel from which tableau powder fumed a blue light, she was so beautiful that tears filled my mother’s eyes.

We did not dislike Lois. We didn’t like her either. You could not say she wasn’t there, when she was, yet in some indefinable way she really wasn’t. Elsie said, “Oh, she’s just a namby-pamby.” But I felt that there was a real Lois, far down inside her somewhere. And I was sorry for her. She was always so good, so proper and ladylike, and if you suddenly asked her whether she wanted this or that, an odd confusion came into her eyes. She didn’t know what she wanted; she had to have a rule to go by, and she’d say, “Well, I don’t know if mama — ”

“Oh, shoot your mama!” Elsie shocked us all. “I’d have a mind of my own, I guess, mama or no mama!”

“That is not a nice way to speak, Elsie,” said Lois, perfectly reproducing her mother’s dignity. Even Elsie was squelched. Lois was right, of course; it was not a nice way to speak.

We were seventeen then. Some were already keeping steady company and all of us had beaux, except Lois. She said, “Mama says I’m too young,” and didn’t seem to mind. In spite of her beauty and her clothes, no boy paid any attention to her until the night Dan Murphy taught her to skate.

She was outdressing us all that winter. It was the winter Mrs. Sherman died; not that we marked time from that event. The Shermans’ square white house was only a little way from ours, across the street, but I had seen Mrs. Sherman only when she was polishing windows or hanging out clothes. She slaved her whole life away taking perfect care of that big house which no one ever set foot into; not even Mr. Sherman, for in order to save the house they lived in the kitchen and its lean-to bedroom. A bedraggled wisp of a woman, she was so timid that if you knocked at the locked door, she wouldn’t answer, fearing tramps. So no one missed her except Mr. Sherman. But her going had been, you might say, a blessing for Mrs. Estes. Mr. Sherman was the station agent; he made good wages and had no time to cook. Mrs. Estes sold him bread and baked beans, cakes and pies, and spent the money on Lois.

“The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach,” Mrs. Rogers said, but my mother pooh-poohed her. “Mrs. Estes’d never set her cap for any man, and his wife not cold in her grave. No, all she’s thinking about is more falderals for Lois.”

I wasn’t interested. The mill pond had frozen, and for a little while a madness came upon us; we forgot we were young ladies now. Our mothers shook their heads dubiously, but on those starlit evenings sparkling with frost they couldn’t keep us indoors. A bonfire crackled and blazed by the pond; the keen air bit our cheeks and blew in steam from our mouths, and all the good ladies were faintly scandalized by our loud shouts and laughter.

Elsie and I were tightening our skates in the firelight when Dan Murphy came swooping toward us, and my heart thumped at my ribs. Dan was black Irish, like his father, the blacksmith, and he’d set any girl’s heart thumping. It was impossible to say why. Mothers didn’t approve of him. In that instant while he was flying toward us on one skate, I remembered how wild he was; he’d fight anybody at the drop of a hat; he played cards and was suspected of smoking; he loafed around the livery stable and the barber shop and spent money as fast as he got it and would never amount to anything, but my heart was pounding with a hope that he’d skate with me instead of with Elsie.

He wasn’t even good-looking. His nose had been broken in a fight and one of his flashing white teeth was crooked. He was wearing ragged overalls and an old jacket, and he had lost his cap somewhere. His black hair was intensely alive: a lock was always tumbling across his forehead, and when, with a quick jerk of the chin, he tossed it back, my very bones seemed to melt. Dan Murphy could have gone with any girl in town, no matter what her mother did. But no girl had ever got him.

His eyes narrowed when he smiled, and the dancing twinkles in them would dance out of reach if you tried to catch them.

“Hello, girls!” he said, and without a pause, “Come on, Lois.”

Elsie and I were too staggered to answer him. We had forgotten Lois. She was there only because my mother wouldn’t let me come alone, so I’d brought her. Elsie had lent her an old pair of skates and she’d buckled them on, but didn’t dare try to step.

“Oh, th-ank you — I ca-can’t — ” she said, teetering. Dan Murphy didn’t say anything. He gripped her mittened hands firmly, and the next instant they were gone. She couldn’t fall; he was too strong, and he was the best skater on the pond.

He didn’t leave her, and every time I passed them I was more astonished. Lois wasn’t like herself at all. I saw her, breathlessly laughing, tear off her coat and fling it on the snow. Most of us had taken off our heavy coats, but not with such abandon. Her pale blue, beaded woolen fascinator kept slipping, till she flung it away too. The tossing curls grew more and more tangled, and she laughed as I’d never heard her laugh. So did Dan. Everyone was noticing them, and Lois didn’t care. That was the incredible thing — that Lois didn’t care. Her laughter made me feel queer.

I was sober, feeling responsible because I had brought Lois. Indeed, we all grew quieter than usual. Long before ten o’clock I took off my skates and said to Elsie, “I’ve got to take Lois home.”

“You’ve got to, all right,” said Elsie. “But will she go?”

“Lois?” I said. “Why, of course she’ll — ”

Those two came swinging down the middle of the pond, so carelessly swift that others got out of their way. They were swaying as if they were one person and each flying stroke ended in their wild crescendo whoop. Lois, her hair uncurling, her mouth open, yelling, and her shape showing under the blown cashmere dress, flashed by so quickly that I almost succeeded in not believing what I saw. Before I could catch my breath, Dan was spinning her around him at arm’s length. They’d just missed going headlong into the snow banks. Still on one skate, her petticoat ruffles plainly to be seen, twice she circled around him, then they crashed together in what might as well be called outright a hug.

Lois was merrily laughing, and Dan yelled, “Ooooopeeeeee!”

“Well! If that don’t cap the climax!” said Elsie.

I walked straight up to them and said, “Lois, we’re going home.”

“It can’t be ten o’clock,” she said, and suddenly I felt that she wasn’t Lois. Her voice wasn’t the same, nor her eyes. Even her rosy face seemed less soft, as if her whole body, like her voice and her eyes, were rounded out, full of a girl I didn’t know. I wasn’t sure I could cope with her.

Dan said No. 5 hadn’t gone through yet. “If you’ve got to go, run along,” he said. “I’m taking Lois home.”

She laughed at him. “Are you?” I knew he hadn’t asked her. “Oh, don’t go yet, Ernestine,” she said carelessly. “I want to skate some more.”

From another girl the words would have meant nothing. But to hear Lois say them, in that sure voice, almost unnerved me.

“I am going,” I said firmly. “And what will your mother say?” I knew well enough that no mother would allow a girl to behave as Lois was behaving that night, especially with Dan Murphy; and I’d brought her, I could be blamed. Mrs. Estes always aroused my sense of self-preservation.

The color went out of her cheeks and I knew she’d come with me. There was never any resistance in Lois. After all, she had been brought up to do as she was told. Hesitant again, she looked at Dan to tell him good night. He spoke first.

“Rats!” he said, swinging her into skating position. “I’ll get you home by ten o’clock.” They were so far away that I couldn’t hear her reply.

I could do no more. Besides, Lois was no longer making an exhibition of herself. She and Dan were still skating decorously, swinging along together and talking, when my beau took me home. He stayed some time at the gate and it was precisely two minutes to ten by the dining-room clock when, all but frozen, I went in.

My mother, who had been sitting up for me, put away the sock she was knitting.

“Did you and Lois have a good time?” she asked kindly, and I replied, “Yes, mama.”

It was no conspiracy which kept Mrs. Estes from knowing what was going on. With parents it was always prudent, as well as respectful, to be silent until spoken to. And there was nothing definite to tell. We simply knew that Dan Murphy was gone on Lois and that she wasn’t discouraging him. Their eyes said that. In one way and another they saw a great deal of each other, not secretly, yet not quite openly. She didn’t, for instance, let him see her home from church; all that next summer they didn’t go buggy-riding, and when he asked to buy her ice cream at the Ladies’ Aid socials, she said, thank you, she didn’t care for any.

I think they quarreled about it. One autumn evening I passed them at the corner of Mr. Sherman’s yard, where the side street went to Mrs. Estes’ house. They were standing there, talking. Chrysanthemums, I remember, were ghostly along the fence and there was a scent of burning leaves. Dan was speaking vehemently:

“But why can’t I? What are you afraid of? What can she do?” Lois made some warning gesture and he was silent till I’d gone by. But, walking softly, I heard him ask, “We’ve got to tell her sometime, haven’t we? Lois? Haven’t we?”

When I told Elsie we were sure that Lois was secretly engaged. We were thrilled. This was the single romance in our experience which was one bit like the romances in books. We cultivated our friendship with Lois as we had never done before, partly from curiosity and partly from a mystic feeling that some magic might be communicated to us. I wondered endlessly how she had got him to pop the question.

She was changed, and not only because at last her mother had put up her hair. Mrs. Estes arranged it beautifully; the huge pompadour and piled coils made her head enormous. Beneath that marvelous golden weight, her face was like the flower faces in children’s picture books. But if she had been vague before, now she was quivering. The slightest incident, sometimes even a word, would throw her into excited laughter or tears. “Oh, I don’t know!” she’d say, sobbing. “It isn’t anything. It’s my hair, it makes my head ache.” Once she said appealingly, “Oh, Ernestine, don’t you wish we didn’t have to grow up?”

I hadn’t thought about it. “We don’t have to do anything,” I said. “We just do grow up.”

It must have been a May evening when my mother and I noticed the light in an upstairs window of the Sherman house. We were sitting on our front porch. I remember the slender moon and a feeling of springtime, and the maple leaves were young.

“What can be going on in that bedroom?” my mother wondered. “He can’t be dressing up; it isn’t prayer meeting night.”

Our side gate clicked and Mrs. Rogers came around the house, holding her skirts above the dewy grass.” You suppose that he’s moving in up there? Poor soul, she must be turning in her grave.”

“Take the other rocker,” my mother said. “Well, it’s no disrespect now if he does get some good out of that big house. Let’s see, was it a year in January? I remember the ground was frozen.”

“February third,” said Mrs. Rogers. “And you can’t tell me he didn’t begin taking notice again, last winter. All that traipsing back and forth; it wasn’t just pies and cakes he was after.”

We could make nothing of the shadows on the window shades. The lamp went downstairs; light glimmered briefly through the colored glass in the front door. Then the house was dark, until a lantern came around it. Pepper-and-salt trousers legs moved scissors-like in the glow.

“His Sunday clothes!” Mrs. Rogers exclaimed. The lantern twinkled down the side street beyond the pickets. My mother settled back then, and so did Mrs. Rogers, exclaiming, “What did I tell you!”

“And a good thing for both of them,” said my mother.

“Yes, Mrs. Estes won’t refuse him, a good man and a good home and all. I wonder how Lois’ll take it?”

“Lois’ll have nothing to say about it,” replied my mother. “And it’s high time her mother’s mind was on something else for a change. You mark my words, if Mrs. Estes don’t let up on that girl, Lois’ll break out somewhere in a way you’d least expect.”

Next day, like a bomb, the news burst upon us that Mr. Sherman and Lois were engaged.

I couldn’t repress a gasp, but my mother remained properly composed. Sitting in our parlor, her hands folded in her lap, she smiled politely at Mrs. Estes and at Lois. “I’m sure I wish you every happiness, Lois.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Allen,” Lois murmured. The thick lashes hid her eyes and she had never had much color. The air seemed heavy, yet dangerously unstable, as though it might explode. I didn’t dare speak.

“Mr. Sherman is a good man,” my mother said carefully.

“Yes, a most suitable match in every way,” said Mrs. Estes. Her sallow skin glowed, and so did the small eyes sunk against her big nose. She was a lady from the hem of black skirts to the velvet-and-jet toque she’d made from scraps of Mrs. Miller’s dresses, but I thought of tigers, of a tiger purring triumph. She purred satisfied pride and love. “He’s all I ever dreamed of for her.”

She had saved the announcement until the end of the15-minute formal call. Now she rose, and so did Lois. I had to say something: “Oh, Lois, I hope you’ll be awfully happy.”

Her lashes quivered upward. She seemed even more confused than I was. My mother was supposing they hadn’t yet set the date. “In June,” Mrs. Estes almost caroled. “I always said Lois should be a June bride.” We all began saying, “Goodbye, goodbye. I am glad you called; call again.”

My mother and I watched till they reached Mrs. Rogers’ gate. Yes, they were calling on Mrs. Rogers. Weakly my mother sat down. “My goodness gracious me, never in all my born days — She’s been maneuvering it all this time. For Lois. We might’ve known. But — but, my goodness Keep watching, Ernestine, and tell me when they leave.”

Before sunset the town was a stirred beehive. Mrs. Rogers declared it was a sin and a shame, marrying that poor girl off to a widower old enough to be her father. Mrs. Miniver said the sooner a girl was settled the better, nowadays; what with all the wild goings-on, you couldn’t tell what might happen. My father came home early, only to be disappointed when my mother told him the news before he could tell her. She said that, after all, mothers knew what was best for a girl’s happiness. But I knew she was saying something quite different to Mrs. Rogers, after she’d left me alone in the house to do the supper dishes.

I was meditatively stirring the cooling dishwater round and round in the pan when whirlwind and thunder came upon me. There was a clatter. I whirled to confront Dan Murphy’s wild face. He had to see Lois, he shouted; I had to help them. “You’re her best friend, you’ve got to! I tell you I won’t stand it! Don’t stand there like a fool! I’m going to see her, I tell you! You’ve got to!” He propelled me out of the kitchen; his grip hurt my arm while I tried to dry my hands and take off my apron, making incoherent protest and inquiry.

“You can get in,” he told me. “You’re going in there and tell Lois I want her.” He swore at Mrs. Estes with a fury that intoxicated me. I had never heard such language. There had been a violent scene of some kind. “She can’t throw me out of her house; she can’t get away with it!” was his description. Trotting beside him and pushing loose hairpins into my hair, I prayed that my mother wasn’t seeing me from Mrs. Rogers’ porch. We hastened through a faint haze lighted by the unseen moon. Mr. Sherman’s house looked flat as pasteboard, and trees loomed gigantic.

“But — what do you want me to say?” I hesitated at Mrs. Estes’ gate. The house was dark, the shades down; only a sliver of light showed under the warped door.

“What do I care? Get her out here,” Dan said.

In the very heart of drama, I didn’t feel so adequate as I had always thought I would be. Something told me that Dan would be wiser to wait a while. I tried to convey this wisdom to him. “But,” I began again, “if you really love her, might — ”

“If I — You don’t know what you’re talking about!” he exploded.

“Sh-h-h,” I breathed. “But after all, maybe — ”

“Yes, she does,” he said harshly. “I know. I tell you I know she does, and she knows it, if she only had the nerve to. Now, will you stop asking questions and get her out here?”

Desperately contriving a plausible lie, I stole up the walk. In Mrs. Estes’ front room there was the faint, recurrent swish of skirts in a rocking chair. I knocked.

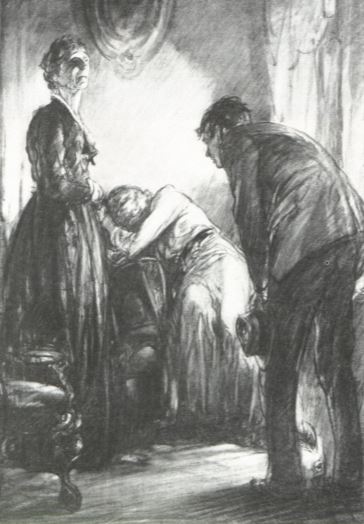

What I’d interrupted was clear. Mrs. Estes had been holding Lois in her arms. The empty chair still swayed; Lois stood near it. I could see only Mrs. Estes’ silhouette blocking the lighted doorway.

“Good evening, Mrs. Estes,” I began breathlessly. “I thought I’d run in just a minute to — Oh, hello, Lois. I — ”

Mrs. Estes did not move. “I am surprised at you, Ernestine,” she said, in that cold tone which indicates no surprise whatever — indeed, the reverse. “Your mother will not approve, I’m sure.”

“But, Mrs. Estes, I don’t know wha — what — ”

“You can tell that young man that Lois wants nothing more to do with him,” said Mrs. Estes, and Dan Murphy was there in one bound.

He was terrific and pitiable. After crying out, “No, no, Dan, no!” Lois collapsed and wept.

Mrs. Estes remained impregnable. Her manner said that Dan’s words and actions were in the worst possible taste. As always, she was right; they were.

Again and again he refused to leave until Mrs. Estes let Lois talk to him, though she told him that Lois didn’t want to.

At last she turned to Lois, huddled and sobbing in the rocking chair. “Lois, have you anything to say to — this young man?”

For a long moment there wasn’t a sound. Then Lois sobbed again.

A roar came from Dan. He swore; he accused Mrs. Estes of unspeakable cruelties; he begged Lois to be brave and to do something, it wasn’t clear what. Of course she couldn’t marry him: he hadn’t a penny.

“You are making an uproar to start the whole town talking and ruin her character,” Mrs. Estes told him, and that was true. “She wants you to leave her alone. . . Don’t you, Lois?”

The silence was not so long this time. Mrs. Estes repeated sharply, “Lois!” and Lois sobbed, “Yes.”

“You devil!” Dan shouted. “It’s a lie! Lois, don’t let her! Darling, you don’t mean it!”

“Will — you — go and leave my poor girl in peace?” Mrs. Estes said.

“Tell me it isn’t true!” Dan raved. “Tell her to go to hell! You won’t marry him, will you, Lois? You won’t let her! Speak to me, Lois, for God’s sake!”

“Lois, you must put a stop to — ” her mother was saying, when Lois screamed, a thin, high, piercing screech. Her face came up from her arms, blind, convulsed, screaming: “Go away, go away, go away and leave me alone! Leave me alone!”

Mrs. Estes softly closed the door behind us. My legs were quivering, I stumbled in the ruts of the side street. With a shock I perceived that Dan was sobbing — walking along with his fists in his pockets and his shoulders hunched and sobs tearing his chest. I didn’t say anything.

At the sidewalk we stopped. Two rockers creaked on Mrs. Rogers’ porch, and I thought I’d better get home through the alley and our back yard. I yearned to tell Dan how sorry I was, and timidly I touched his sleeve. “Dan — ”

“Oh, go to hell!” he cried, striking my hand away. That was the thanks I got. I was not surprised next day when my father told us that Dan Murphy had got rip-roaring drunk and fought the night watchman. “Took three men and his father to handle him,” he said, not without admiration. “That fellow can lick his weight in wildcats.”

Of course, that ended my knowing Dan Murphy. Even had I not given the solemn pledge that lips that touched liquor should never touch mine, no nice girl could know a man who drank. Reason told me that Mrs. Estes had acted for the best.

By a good fortune only too rare, I had reached our kitchen unseen. The scandal was dynamite which I longed to explode, but I couldn’t think how to explain my own part in it, and the first sight of my unsuspicious mother told me that silence was safety. I dared not trust even Elsie. I could speak only to Lois, and she retreated into herself like a snail.

“But, Lois, do you love him or don’t you?” I persisted hardily.

She was a timid thing, venturing, “How can you — Do you know how to — to tell, for sure? Do you, Ernestine?”

“Well, you just know,” I replied with assurance. “You don’t have any doubts about it — not if it’s real love.” We always said those two words with awe.

She murmured, trembling, “It’s so important — all your life long — and if you made a mistake — Mama says nice girls don’t ever know.” Her voice steadied: “Real love comes after you’re married. If you marry a good man you respect.”

Of course, we all fluttered about her in envious excitement. She was the first of us to be a bride. And she was making a match which we could only hope to equal. Her mother was sewing day and night, making her clothes. She had a diamond engagement ring. She would step right into that big house with all its furniture as good as new, and she’d never have to stint herself for anything she wanted. She was going to the St. Louis World’s Fair on her honeymoon, and when she came back she’d be Mrs. Sherman. Not even Mrs. Miller could look down on Mrs. Sherman.

When I thought of Mr. Sherman I felt a faint chill. He had always been simply Mr. Sherman; I had never really seen him before. Now I looked at him and could find nothing to dislike. His heavy gold watch chain curved across a front more portly than my father’s, but he was not fat. He had a gravely serious manner, suited to his position; he was a pillar of the church and superintendent of the Sunday school. He was really a good man too; strictly businesslike, but not merciless to the farmers whose mortgages he held. His large face was serious and rather heavy, with thick-lidded eyes of no particular expression, and all the lower part of it was brown whiskers, cut short and square. They were always neatly trimmed and combed. His clothes were of good substantial material and his clean hands, with blunt fingers and uncalloused palms, showed that he was able to hire work done for him. Nobody could object to anything about Mr. Sherman. He had proved that he was a good husband and a good provider.

Lois would not tell us how he had popped the question. Under Elsie’s prodding, she admitted that she hadn’t expected it.

“Did you think all the time he was making up to your mother?” Elsie asked.

Lois was startled. “Why — why, of course not! Whatever gives you such a — ”

“Oh, nothing,” Elsie said airily. “Only he’s more her age, and all. I bet he’s her ideal. I think you’re simply mean, Lois, but anyway tell me one thing — aw, please? Is it just wonderful when he kisses you, or do his whiskers tickle?”

“Elsie Miller!” I exclaimed. Lois was red as a beet.

Elsie was brazen. “Well, I don’t care! You know they say, ‘A kiss without a mustache is like an egg without salt,’ and I think Lois might tell us. He’s got mustaches and whiskers both.”

“It isn’t proper to be kissed till you’re married,” Lois said.

“Why, Lois Estes, it is too! It’s perfectly all right to be kissed as soon as you’re engaged. You mean to say you don’t even let him — “

“Oh, please, don’t!” Lois cried, and I said severely, “You shut right up, Elsie; be ashamed. Nice girls don’t ask such questions.”

It was a church wedding. The day was June’s perfection, and everyone said, “Happy is the bride the sun shines on.” There was not a vacant place in the church. The flowery lawns and silks and the flowers on new spring hats made it look, my mother said, just like a garden; though we had never seen a garden with anything in it but vegetables. Elsie Miller sang, Oh, Promise Me, and Mrs. young-Doctor Wright played on the organ, Here Comes the Bride.

Lois carried white roses. Their fragrance went up the aisle with the shimmering pure lengths of China silk and the misty veil, and its passing by seemed the passing of all lovely things — the sweetness of simple faith and unconscious hope, of dawns and noons and evenings twinkling with fireflies, of sun and wind and stars, and of all small homely matters, the sweetness of life itself. So that our awareness of the moment even then, in our first perception of it, eluding us and lost forever, was too poignant to be borne without tears.

“Beats me why women got to cry at weddings,” my father muttered huskily, turning his face from my mother’s wet glance. When the bride’s trembling voice repeated the irrevocable oath, “to love, honor and obey till death do us part,” sobs could not be choked.

Mrs. Estes had worked her fingers to the bone to make it a perfect wedding, and it was. Everything went off without a hitch. Lois, pale and remote in a bridal daze, was more beautiful than words can say. Her wide eyes saw nothing, and she quivered at a touch. Mr. Sherman, sleek in a new pepper-and-salt suit, plainly had a realizing sense of his responsibility and was able and willing to shoulder it. Her mother got her into traveling clothes for the train to St. Louis.

Climbing into the coach, she stepped blindly on her skirts and stumbled; Mr. Sherman seized her arm. Handfuls of rice were pattering; every train window was full of heads; we were all laughing or cheering. Lois glanced back at us and my heart contracted; her eyes were silent screams of terror. Trapped, I thought; no escape now, never any escape, all her life long. Mr. Sherman’s ponderous back came between us, and the grinning black porter mounted the steps.

It was over. The steel rails hummed behind the diminishing train. There was no Lois anymore; she was Mrs. Sherman. In her fawn-colored suit with bands and revers of brown velvet, with the little toque of massed violets on her golden hair and a tiny dotted veil to the tip of her small nose, she must begin now to love Mr. Sherman.

Tears dripped down Mrs. Estes’ sallow cheeks. But they were tears of joy, dried more by triumph than by her damp handkerchief. “I haven’t lost a daughter,” she said. “I have gained a son.” Nobody, she repeated, could be more generous, more kind and thoughtful; ‘a Christian and a gentleman in every way; she couldn’t want a better man for Lois. “I could die content now,” she said. “I’ve nothing more to wish for.”

“Well, it’s been all her doing,” my mother said. We walked sedately homeward in our best clothes. “And anyone can see she’s satisfied. I’m sure I hope it turns out for the best.”

From delicacy, we crossed the street to avoid passing the blacksmith shop. Mr. Murphy was striking showers of sparks from the iron on the clanging anvil. He would be ashamed to speak to us, for Dan, drunk and disorderly, had been arrested the night before. Dan was even then in the calaboose serving a two days’ sentence.

“That’s true, you never can tell,” said Mrs. Rogers. “But Lois might have gone farther and fared worse.” The words were as final as an epitaph. In those days all stories ended with the wedding.

Indeed, when Mr. and Mrs. Sherman came home, she had settled down. She was quieter and, if possible, even more proper. We called, dressed for the occasion and carrying our card cases, and she showed us pictures of the World’s Fair. In the parlor with its rich carpet, lace curtains and heavy furniture of real mahogany, we turned the album’s pages with gloved fingers and murmured what a privilege it had been to see such buildings and such flowers, and lighting by electricity.

“Yes.” Lois said.

“Look at this one.” Mrs. Estes was uplifted by pleasure. “They walked right along here. Just like paradise. Wasn’t it, Lois?”

“Mr. Sherman and I enjoyed it very much,” Lois said.

Mrs. Estes had rented her little house. Mr. Sherman was glad to have her live with them, and she did all the housework. She had never let Lois spoil her hands.

This exasperated Mrs. Miniver. “Too lazy to breathe! A married woman that don’t do a hand’s turn! It’s downright selfishness. Her poor mother’s given her whole life up to that girl, and what thanks does she get for it? The more you do for such folks, the more you can do.”

At first we girls ran in less formally to see Lois and her house. We admired the large square rooms and the good furniture so well taken care of by Mrs. Estes. The lean-to bedroom was not used any more. Mr. Sherman and Lois slept in the upstairs front bedroom with its massive walnut bed and matching bureau and washstand. The room was so neat that it seemed a little chilly. Lois had not changed it at all, and left nothing of hers lying about; everything was precisely as the first Mrs. Sherman had kept it.

“Yes, it’s a nice room,” Lois said. She agreed to everything we said about her house.

When Elsie asked outright how she liked being married, she replied in the same colorless way that she couldn’t complain. “We have to get married,” she said, “and Mr. Sherman is a good man. I try to be worthy of him.” Sometimes we were there when he came home. He was dignified and bland.

Lois met him at the door as a wife should, took the meat he had brought for supper and hung his hat on the hall rack for him. Young married women were then, among friends, calling their husbands by their first names but Lois always said, in the old fashioned way, “Mr. Sherman.”

“Blind Booth is coming next week Would you care to go?” he’d ask, and she would reply, “Just as you like, Mr. Sherman.”

They would go sedately and sit side by side in the opera house above the Racket Store, hearing the blind Negro play the piano. Then they would walk home again. She and her mother accompanied him to church, and at his request she took a class in Sunday school. She was definitely a married woman. Our mothers still masked anxiety, but Mrs. Estes rested in complacency.

Lois would undoubtedly live all her life as she lived the first two years of her marriage. The stork had not yet visited her, so probably it never would. She need not dread widowhood, though she was so much younger than her husband, because Mr. Sherman’s health was as substantial as everything else about him. His father had lived to ninety-six, his mother to eighty-seven. He often referred to their long lives and said that he didn’t feel a day older than when he was twenty.

My mother could hardly believe her ears when she heard that Mr. Sherman was down with typhoid fever. “Not Mr. Sherman!” she exclaimed.

It was the beginning of a nightmare summer. Within a month typhoid was in almost every home; whole families were down. Both doctors were working day and night; women abandoned housework entirely, eating when they could and snatching sleep when they could be spared in sick rooms. Disheveled and sandy-eyed from night vigils, we exchanged news in passing. More help was needed south of the tracks; Mr. Murphy had passed away; Gerty Bates was very low; both Mrs. Miniver’s girls were down now; old Mr. Whitty might not pull through.

The church bell tolled. We counted the funeral strokes, and the August weather seemed to have ‘a chill in it, the sunshine to be a false aspect of darkness.

Mrs. Estes was wonderful; nothing would persuade her to rest. Lois, of course, did all she could, but Mrs. Estes had never allowed her to do much. Now she took the whole care of Mr. Sherman upon herself. All the passionate intensity that had poured itself upon Lois now poured into keeping this husband alive for Lois. Her eyes burned deeper in her strained face; the sallow skin stretched taut over cheekbones and jaw. Mr. Sherman’s flesh had fallen off him. He was a foul and raving thing of skin and bones, on the walnut bed in the smothering room. Mrs. Estes bathed him every two hours, day and night. She held him when he fought her in delirium; she kept the covers over him when he tried to throw them off. She would let no one else give him medicine, dole out his spoonfuls of water and broth. She was magnificent and terrible.

The doctor himself gave her no hope. For sixteen days the fever burned unbroken, climbing higher. Day after day he was consumed by a heat that no living thing could stand. There could be only one end.

“We’ll lay him out today,” Mrs. Rogers said one morning. She had come to summon my mother. Even Mrs. Estes admitted that he was sinking into the last sleep; Lois had been at the bedside all night. “Poor soul, I wonder how she’s taking it?” I did not know whether she meant Mrs. Estes or Lois.

It seemed strange that anyone could die on such a morning. Beneficence poured from the sky, hens cackled in barnyards, and No. 4’s whistle cheerily echoed from the cut. I swept the porch slowly, in a dreamy awareness of time’s passing over the earth with the sunshine; summer was going, soon winter would come, then summer again, and at last the seasons passing over the earth would know nothing of me, nor I of them. But I did not believe it. Young Doctor Wright had gone into the Sherman house and, shocked, I caught myself thinking how pretty Lois would be in widow’s weeds. Thoughts must be controlled; triumphantly virtuous, I did not think of Dan Murphy. Nothing, I told myself, was farther from my thoughts, as certainly it must be from hers. And a terrible shriek ran up my spine and crinkled under my back hair.

I stared at the Sherman house. The shriek became a wild, uncontrollable sobbing. In a flash, while I ran, I saw that scene of tragic widowhood and wondered whether, with all that money, Lois would marry a mere blacksmith. The front door stood open to the unkempt hall and, amazed, I saw Mrs. Rogers coming downstairs. She urged me back to the porch.

“Sh! We must keep him quiet,” she murmured.

“Him?” I gaped at her. “Who?”

“Mr. Sherman’s improving; the doctor just said he’ll get well if Mrs. Cleaver reached us, and two or three others were coming. Those sobs upstairs were choked now; my mother’s firm tones could be heard.

“But that’s Lois, crying! Like that!” someone said.

“Yes. It’s — shock,” said Mrs. Rogers. “I guess.” The pause trembled with words that might be said, but weren’t. “Anyway, that’s what the doctor says: Shock. When we expected — He was getting cold at six this morning.”

Mrs. Cleaver gasped, “Did you ever!” and added hurriedly, “Well, no wonder — ” Everyone said hurriedly, yes, yes of course. Of course it was the shock, poor thing; such sudden good news and she so high-strung after those weeks of strain.

Mr. Sherman’s recovery was miraculous. Daily his fever was less, till at last he lay weak and thin, but himself again. He would get well; it was only a matter of time and of liquid diet. “Wait till you’re up and around again, good as ever,” the doctor told him jovially. “Then you can eat steaks and fried potatoes, all you want.” The patient’s outburst of temper was nothing to worry about, he said; it was another good symptom.

A blessed calm fell upon us; the epidemic was over. Wherever women met, they said they thanked God it had been no worse. With joy we attacked the delayed house cleanings and gossiped again across side fences. There was plenty of neighborly help in taking care of Mr. Sherman. He was mending; daily his temper grew worse and he demanded food so constantly and violently that even Mrs. Estes lost patience and my mother told him tartly, “You get what the doctor orders and not one sup more. We don’t want to bury you.”

Lois was an angel with him. Nothing he could say disturbed her quietness. She was thinner; shadows made her eyes enormous in the small pale face, and the golden hair was too heavy for her head, but she was still beautiful. Mr. Sherman’s eyes followed her while she went quietly about, carrying out basins and bringing towels, setting chairs in place. “Come here,” he’d say, and she came.

“Sit down, can’t you!” She did not mind his crossness; she sat down. He’d ask her, “Glad I’m getting well?” and she’d say, “Yes, of course.” She would sit for hours by the bed, doing nothing, looking at the idle hands in her lap. The thick gold wedding ring was loose on her finger.

When he spoke, she said, “Yes, Mr. Sherman,” and fixed his pillows or gave him a drink of water.

I had seen this so often that I knew what to expect when one afternoon I came into the still house. Everything was perfectly clean and in order; doors and windows were open to the balmy September day; nothing stirred but a fluttering curtain. The hush made me tiptoe before I realized that Mrs. Estes must be asleep. Carrying my bowl of steaming broth, I went noiselessly upstairs. The bedroom door stood open and for an instant, on the threshold, my mind rejected what I saw.

Mr. Sherman sat propped against pillows, and Lois was bending over him. Her whole body breathed angelic tenderness and an angel’s smile beamed from her face. I was not mistaken; it was a scene of pure love.

Her voice was sweet with selfless joy: “Would you like another, Mr. Sherman?”

Her two hands held a platter heaped with steaming sweet corn. Mr. Sherman laid down a gnawed cob and grasped a plump ear. “Butter,” he said.

“Lois!” I screeched.

She started and turned a clear gaze on me. The smile lingered in her candid eyes. “Mercy, you scared me!” she exclaimed. “What? What is it, Ernestine?”

“Don’t!” I cried. “You mustn’t!” The broth was slopping on my hands and I couldn’t find a place to set down the bowl. Mr. Sherman gnawed wolfishly. “You know better!” I told her. “Stop him!”

“Stop him what?” she asked, bewildered. The sense that Mr. Sherman was a sick man weakened my attack. He left a partly denuded cob in my hand and seized another ear. “What are you doing?” she asked me in shocked disapproval.

I said she knew it would kill him. She murmured dreamily, “Oh, no.” Mr. Sherman, ravenously munching, growled something about fool notions, starving a man. I noticed spots of melted butter on his nightshirt.

“The doctor told you!” I said furiously.

“Did he? I don’t remember,” she replied vaguely. Terrific power suddenly rose in her; in a voice I’d never heard, deep, resonant, vibrant with emotion, she said, “The doctor said nothing of the kind. Nourishing food will do him good.”

All this had occurred with utmost rapidity. I couldn’t have been half a moment in that room. I burst into Mrs. Estes’ bedroom, shouting. I sped across the street to my mother, and on her orders ran for old Doctor Wright. He was out on a country call. In a nightmare effort to hurry, I reached the other end of town. Young Doctor Wright was out too.

I forced quivering legs to bear this news to Mr. Sherman’s bedroom. It was crowded. He looked quite well. There was color in his sunken cheeks; the barber had shaved them and trimmed his beard that morning. He said doctors didn’t know anything; he felt well enough to get up right now. But he was watching the door.

Lois sat by the bed, shrinking from the looks cast at her. “Well, I didn’t know,” she breathed, trembling. “I don’t remember, really.” While her worn-out mother slept, Lois had gathered that corn from the garden, stripped the ears and boiled them, and carried them upstairs to Mr. Sherman. He had eaten eight. “He told me to get him something to eat,” she pleaded. “He was so hungry. I only thought — ” She twisted her handkerchief.

Old Doctor Wright came at dusk. Mrs. Estes lighted a lamp. Still dusty from the country trip, he listened while she told him what had happened; he took Mr. Sherman’s temperature and pulse. Lois watched him with terrible intensity. The click of his watchcase, snapped shut, made us all start. “Well, well, been cutting up didos, uh?” he said cheerfully. “Feeling pretty good? That’s fine. Take it easy, now, and don’t worry. Couple these good ladies’ll stay with you tonight, and I’ll be around again in the morning.”

We made way for Mrs. Estes and Lois to go with him into the hall. He beckoned my mother and Mrs. Rogers with a glance, and shut the door.

Mrs. Miniver said at once that she must get home to see about supper; so did Mrs. Miller, and defensively I thought of my father’s supper too. Mrs. Miniver opened the door. But the hall was empty.

Downstairs the parlor door was shut. We hesitated on the porch; it wasn’t right to go without knowing what the doctor said. The windows were open and the parlor lamp lighted. The doctor and the women were looking at Lois. She stood trembling and crying. “But I didn’t mean — I didn’t remember you said not to. I don’t remember. I can’t — ” her voice rose.

“There, there, of course you don’t, Mrs. Sherman,” the doctor said. “Of course not; we all know that.” There was a queer look on his face. Watching her under his bushy eyebrows, he shook some tablets into a twist of paper and gave it to Mrs. Estes. “Get her to bed right away. Two of these in water, and two more in an hour if she isn’t asleep. Come, come now, Mrs. Sherman; you mustn’t give way. Sorrow comes to us all.”

“Come, Lois,” Mrs. Estes said, as if she didn’t want to. She moved to put her arm around Lois, and quick as a cat, Lois turned on her.

“Leave me alone! Don’t touch me!” In the lamplight her face was hideous. “I can’t stand it! I can’t stand it! Leave me alone! I hate you, hate you!” Suddenly she screamed out the word that no one had said: “Murder! Murder! You killed him! Don’t touch me! Take her away! Don’t let her touch me!”

The old doctor picked her up, jerked open the parlor door and carried her, struggling and screaming, upstairs. Mrs. Rogers scurried after them; my mother ran to the kitchen. The hall was a babble.

“Lord save us, she’s gone stark raving — ”

“She don’t mean it, Mrs. Estes; they always turn on them they — ”

“You don’t mean she — ”

“What did she say? I didn’t — ”

My mother appeared with a steaming teakettle. “Go home, Ernestine. You hear me?” she said from the stairs. I obeyed.

Mr. Sherman lingered two days in agony. The doctor gave him morphine. He died about four o’clock on the third morning.

The funeral was perhaps the largest ever held in our town. We had to wait half an hour at the raw, open grave before the last buggies began to arrive. Mrs. Estes had aged terribly. Mrs. Miller and Mrs. Bates-that-was-Dorothy Brown supported Lois, drooping in rich black crape; the veil hid her face. Horses shook jingles from their bridles, stamped and whinnied. The sky was vibrantly blue and great shining puffs of cloud floated in it. Looking upward, one felt that heaven was a happy place to go to. We knew that Mr. Sherman, equipped with large white wings, was on his way there, or perhaps had already arrived and was even then playing a harp in the celestial choir.

The men with shovels settled to their work while the first mourners drove away. My father went to get our buggy, and Mrs. Rogers said, “They’ll have to patch it up somehow. Mrs. Estes hasn’t got a thing in the world but Lois, and Lois can’t turn her out; her own mother.”

“And just given up her whole life to that girl,” said Mrs. Miniver. We walked slowly down the grassy slope between the headstones; the iris blades were turning brown at the tips. “I must say I feel to sympathize with Mrs. Estes. I never saw anything so horrible as the way Lois turned on her. So much as intimating it was her fault Mr. Sherman passed away; I guess we know whose fault that was! I wouldn’t put anything past Lois. You mark my words, poor Mrs. Estes’ll find out how sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child.”

My mother said cryptically, “Well, she’s good, and she’s smart, and a lady if ever there was one, and she’s acted only for Lois’ good. But you can push a body just so far.”

The moment had for me a pleasant melancholy; I was thinking that never again would I see the sunlight slanting on those graves and the iris tips turning brown. I was going away; for months the day had been set. It came. My father took my trunk in his dray; my mother and I walked to the depot. The Sherman house was blank behind drawn shades; we did not know what had happened between Lois and her mother. Dan Murphy was shoeing a horse when we passed the blacksmith shop. He clapped the iron on the smoking hoof and with rhythmic, sure strokes drove the nails in. In spite of his grime, there was something splendid about him.

My mother wrote me that Lois had sold the Sherman house. She was boarding with Mrs. Cleaver; Mrs. Estes lived alone in her little house, taking in sewing again. “Mrs. Miniver says — ” I skipped. “Dan Murphy has taken the pledge and keeps himself spruced up nowadays. He comes to church regular and — ” The town already seemed far away and dull.

Twenty-five years passed before I returned to the place where it had been. I recognized some old trees in the Square; the Miller mansion was still standing. But I did not know the smiling woman who stopped her car beside mine at the gas pump and cried, “Don’t you remember me? Mrs. Murphy. We used to go to school together.”

“Of course!” I cried, as one does. A stranger looked at me with affection through brown eyes sparkling with life. The silvery pale hair was cleverly cut and waved, the hat smartly defied gravity. She was contented, merry, and full of pep. I rejoiced to think I looked as young as she, and the gaze of her two tall sons and daughter made me feel older than Methuselah. “You must come to our basketball games,” she said. “Ted’s captain this year. Can you believe my youngest’s a senior, and I’m almost a grandmother? Junior is in the garage business with his father.”

I like Mrs. Dan Murphy. We have good times together. Her house and her life are open to all weather, overflowing with energy and fun. There is no pretense in her; she is sincerity itself.

Only last week we chanced to meet at the grocer’s. The vegetable truck from the city had stopped and the driver unloaded a case of Southern sweet corn. Long ago I ceased to control my thoughts, and though I am fond of Lois Murphy, I saw no reason to resist a curiosity invaluable to a writer. I picked up an ear of corn and parted the husk to the clean, milky kernels. “This looks good,” I said.

“Doesn’t it?” she agreed. “But none of us care for sweet corn, for some reason. Dear me, it’s so hard to get men to eat vegetables!” Her eyes met mine. I had known that she didn’t know why she gave Mr. Sherman that sweet corn. Now I know that she has forgotten she did it.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I wanted to read something by Rose Wilder Lane. Now, I want to read something else.

This combines a well-drawn plot with sharp, stark characters. Few of the people are placeholders. They play roles, most of them.

Thanks for making this old story available.

I enjoyed this story very much, with all the details of the time period.