Originally published on April 7, 1917

Originally published on April 7, 1917

When Miss Elizabeth Robinson changed her first name to “Ysetta,” Mr. Brown knew that there was danger of her becoming incurably artistic. Mr. Dennis J. Brown lived with his widowed mother on Maple Hill, which is the guest-towel section of Northernapolis. Mr. Brown was thirty-seven — twelve years older than Ysetta. He was the general manager of the Inland Lumber and Construction Company. He talked quickly, and had a well-shaped nose, and wasn’t too bald, and sang a colorado-maduro barytone, and made eleven thousand dollars a year, and loved Elizabeth-Ysetta true. He had plans for a bungalow, with a vacuum cleaner and Ysetta as modern improvements.

But Ysetta’s plans were entirely different. She had Aspirations, and she was going to have a Career also, as soon as she could decide what to career about. She felt that it wasn’t respectable for one who was Different to be respectable. She tried to make Mr. Brown understand how Different she was; but he would stare at her delicate face, framed in an oval by coiled flaxen braids, and chuckle: “She’s a peach. She’ll make the dandiest wife in town, when she settles down and cuts out the Urges.”

For four years now Ysetta had had a new urge every season. The minute her family got back from the summer cottage at the lake she would catch an Urge. One winter she painted. The next she did interpretative dancing. Her demonstration of Esprit de Printemps, which is believed to mean The Spring Drive, was greatly applauded. It consisted of a foul, a bunt and a long slide for base. But Ysetta caught cold from wearing a dancing costume consisting of faith, hope and a good deal of charity, and she changed her Urge to being Economically Independent.

She borrowed eight hundred dollars from her father and Mr. Brown, and started Ye Precious Shoppe, where she sold tea, cakes, irregular jewelry, and orange tables with scarlet borders — that is, she really did sell some of the tea. She was so successful at being economically independent that she was only a thousand dollars in debt at the end of the season; but her father, who was a large red man with curvature of the waistcoat, grunted that she was a darn sight more independent than economical, and wound up the business.

Ysetta didn’t much mind, because she was coming to see that her Métier — a Métier is an Urge that you cash in on — was to deal in wares more subtle than tables, even orange-colored tables with bright red borders. She decided that she was going to deal in mystical and singing words, and reveal America to itself — in fact, run a Poetic Sightseeing Coach.

Mr. Brown encouraged her — when he had done a few calculations on the office adding machine, and estimated that for the cost of one quite small orange table Ysetta could get enough paper and ink to write two volumes of verse and one long novel. He gave her a box party at the best movie house in town to celebrate her inauguration as a genius. He pictured a future in which his clever wife, Ysetta, would come a-running, bringing a new poem along with his slippers in the evening. Chestnut eyes shining, she would cry:

“Dennis, I have written a poem to you, my hero!”

In intervals of selling laths and portable houses, Mr. Brown tried to keep up with the books she was reading. Now he could get private satisfaction out of the financial columns or the literary efforts of the biographers of Jess Willard and Fred Fulton, but he did not find much entertainment in An Analysis of the Sociological Factor in Realistic Fiction. He was a patient wooer, however, and he even permitted Ysetta to toll him to the Maple Hill Literary and Short Story Club.

The Short Story Club met in the charming residence of Mrs. Solomon Smoot, with its tufted leather chairs and prints of red-coated huntsmen. They were a jolly bunch, very modest and informal, despite the marked talent which had been discovered among them. There was the Reverend Justus Fliff. There was Mrs. Fliff, who wrote the sweetest little sunshine stories, one of which had been published in the Sunday News and had attracted attention all over the state — though you would never guess it, to see the deprecating way in which Mrs. Fliff replied to questions by the less successful writers. There was Nittie Smith, the child wonder, who at thirteen had written more than one hundred poems.

Besides these professional authors, Mr. Brown was introduced to some thirty intellectuals, all of whom showed remarkable promise.

It must be said for feminism that most of them were women.

Cowering behind the gilded pine cone portière, Mr. Brown discovered a large embarrassed male whom he had met at the country club.

“My Lord, what you doing here?” they said to each other, and shook hands desperately, just as Ysetta and the spouse of the large male bore down on them and dragged them out into the parlor, where thirty church-social chairs were arranged in rows.

Mrs. Fliff read a short story which she had written all by hand — she prefaced it by observing that the use of the typewriter explained the low level of style exhibited by the so-called popular writers of the day. She drew a long breath, tucked her hair back over her right ear, smiled nervously at her admiring friends, and read the story, “Dora of the Redwoods.”

It was a virile composition regarding a young woman who resided among the Sequoias, also among numerous handsome mountains and sunsets, but went to the city and got in wrong. The strong silent man back home, who had a heart of gold, even if he did not own a toothbrush, had been waiting for Dora all the time. He went up to the city and brought her back, presumably to tend the redwoods for the rest of her life. Mrs. Fluff gathered her daintily written pages of manuscript, rolled them and tied them with a blue ribbon, and begged:

“I didn’t know how terribly bad it was till I read it to all you terribly severe critics, and now I want you to tell me how terribly bad it is. I don’t want praise — I just want you to say frankly what you think.”

Mrs. Solomon Smoot confessed that “Dora of the Redwoods” reminded her of Stevenson, Jack London and Marie Corelli.

Mr. J. Edwin Bindle wondered if it wouldn’t be better to call it “Dora of the Redwood Forests.” He didn’t, he submitted, wish to be crankorious, and aside from this teeney-weeney point, it struck him as how the story was pos-so-lute-ly perfect. Everyone smiled; Mr. Bindle was so whimsical and original in the words he used. But everyone’s smile became uneasy as the authoress objected:

“Really, I should think you could see that my title is more crisp and powerful. I chose it as having that simplicity which is the brand new keynote in art. Please understand, I do want all possible adverse criticism, it is so helpful; but in this it does seem to me that you are most unjust.”

Everyone stared coldly at Mr. Bindle.

The librarian of the Maple Hill Branch asked Mrs. Fliff if she had submitted the story to the magazines. The librarian said that, from her long professional literary experience, she knew that any magazine would be glad to have it.

“Oh, I guess they wouldn’t care for it,” said Mrs. Fliff bravely, “though I must say that when I read the stupid hackneyed stuff that all these editors do print, I often think I just couldn’t help doing as well as that anyway! Now I want you good people to give me further frank criticism. ‘Tis only by correction, you know, that we can climb to fame and a wider usefulness.”

But it seemed that “Dora of the Redwoods” was one of those chaste gems in which no one, save a smart aleck like J. Edwin Bindle, could find a single fault. One club member pointed out that the dénouement was perfectly splendid, while another preferred the local color and heart interest, and a third moved that they give three rousing cheers for dear “Dora of the Redwoods.”

Mr. Brown, of the Inland Lumber Company, had been suffering in a manner suggestive of a person afflicted with neuralgia at an ice cream party. He had kept himself from saying anything by fingering a cigar in his upper waistcoat pocket till he had cracked the wrapper. Under cover of the cheer he leaned toward Ysetta and humbly inquired:

“Say, am I right? It strikes me that dear Dora is indescribably rotten.”

Ysetta stared.

“Why, no! Of course poor little Mrs. Fliff hasn’t had the opportunities that some of us have, but it’s a very sweet little story.”

“You’ll admit it’s hackneyed, and any fool could guess how it was coming out, and dear Dora is about as human as a crank case?”

“I suppose so.”

“And the story had all the pep of the McMac pages in the phone book, and Mrs. Fliff doesn’t know anything about redwoods — she’s got ‘em balled up with firs.”

“Still, it is a sweet little — ”

“I see. Otherwise it’s all right.”

“Of course it is!”

Ysetta seemed excited over all forms of optimistic fiction, from dear Dora to the charlotte russes which they later got as refreshments. Mr. Brown could not understand her exhilaration.

He did understand, a week after the club meeting, when he received a note from Ysetta informing him that she was going to New York to live. She was to take courses in English literature and fiction writing at Columbia University, and devote herself to the Life Beautiful. He was able to see her only once before she went, and then she was illusive and rather exasperating. She appeared to have been snatched up to a plane higher than his. Only when he took his hat and said despairingly, “I don’t suppose you’ll miss poor old Dennis at all in N.Y.,” did she come down to his level. She ran to him and put her hands on his shoulders. She let him kiss her once.

“Maybe I shall miss you there,” she murmured. “I’ll be such a little nobody in New York, among all those frightfully wonderful Bohemian people. And you are so staunch and good, even if you haven’t any artistic impulses.” She broke from him and skipped upstairs.

Mr. Brown retrieved his good new hat from the floor, rubbed it with his sleeve, put it on carefully, then remembered that he was a lorn lover and assumed a terrific aspect of hopelessness.

“I’ve got to lay in a supply of artistic impulses, then,” he said to himself. “It will raise hob with the lumber business, but I’ve got to come to it. Why not? Never saw the business deal yet I couldn’t pull off. Les-see. I guess I could learn poeting in a couple weeks.”

He went home rather thoughtfully. He took from his prim desk a bunch of discarded stationery. On the back of a letter headed “Lumber that Lasts. Inland Co. for Keeps,” he indited a small poem entitled “Thine Lips, Dear Love.”

He read it aloud.

“Gosh, that isn’t so bad!” he mused.

All next week he read a riming dictionary in the office. “The old man is up to something,” whispered the office force. “Can you beat it — him that always wears two-dollar neckwear coming out with one of those fluffy socialist ties? Betcha a hat he’s going out for amateur dramatics.”

To Miss Ysetta Robinson, in New York, Mr. Brown was writing long biweekly letters descriptive of the state of his business. Miss Ysetta, in short fortnightly letters, replied that New York was very large, and her instructors in college perfect dears, and had Mr. Brown read the latest novel? Mr. Brown never had. But he paid his secretary three a week extra to keep in touch with the bookstores, so that he might be able to write her such passionately intellectual phrases as, “Have you got hold of Gaston Rakowsky’s new novel yet? Tremendous! Never read anything more realistic than R’s description of the back room of a butcher shop.”

With a plaintive hope that Ysetta would approve, Mr. Brown joined the Short Story Club. When Mrs. Smoot, in her cunning way, tapped him on the arm and said: “Naughty, naughty mans! Oo haven’t written one bitsie story yet, and we all want to hear from you so much!” then Mr. Brown understood the pleasures of frightfulness. But he sneaked out for a smoke, and was able to hang on and write Ysetta full details about her admired friends, Mrs. Fliff and Mrs. Smoot and J. Edwin Bindle.

Ysetta never commented on his tidings about the Sapphos and George M. Cohans of Maple Hill. Her letters grew more infrequent. At last, when he asked about her return to Northernapolis, she broke out with one long letter.

She hoped that she would never see the provincial hole again till she was an independent and famous woman, she wrote. Her finer self had been bound by tradition and bourgeois ignorance, in Northernapolis. And at last she had been in Hobohemia.

Hobohemia is the place and state of being talented and free. It is to be found adjacent to the bar of the Café Liberté. In Hobohemia, Ysetta had seen several women drinking ojen cocktails, and heard a man in a sky-blue shirt with a soft collar say that he was an anarchist. She had been introduced to an actor in the Hobohemian Players, and to Max Pincus, the celebrated landscapist, and to Mrs. Saffron, the radical leader; and with her own eyes she had seen Jandorff Fish, the novelist, eating hors d’oeuvres.

Then Mr. Brown realized that it was useless to implore Ysetta to come back. If he ordered hors d’oeuvres in any restaurant in Northernapolis, the waiter would bring a Swiss cheese sandwich. The only thing Mr. Brown could do was to go to New York and become hors d’oeuvry.

He took a three-months leave of the Inland Lumber Company. He estimated that three months would be enough for a man who believed in card catalogues, instead of ojen cocktails and sky-blue shirts, to succeed in literature.

II

Upon the eastbound train Mr. Brown sat in his compartment and wrote short stories. Whenever he found them getting interesting to himself, he decided that they probably were lowbrow, and tore them up and took a fresh start.

Mr. Brown had been in New York before. He knew it as two hotels, seven theaters, six cabarets, three offices, a lumberyard and a subway. He went airily to the Grand Royal Hotel and telephoned to Ysetta.

She did not sound particularly welcoming as she demanded:

“What are you doing here?”

“Just got in sminit. I’m here on business. May be kept in the city for some weeks, working up some deals.”

“Deals! This isn’t the city of deals! It’s the city of the strong red wine of life.”

“Yeh, I know, honey,” he humbly agreed. “I’m going to shoot a beaker of that myself, as soon as I get out of this hot phone booth. But say, Bess — Ysetta — whatcha doing tonight? Can I take you out to dinner?”

“No, not possibly tonight. But you may come up tomorrow afternoon, and I’ll give you some tea.”

Did Mr. Brown spend his first evening in wandering solitary about the streets? No, Mr. Brown did not. Mr. Brown telephoned to the chief lumber jobber in New York, arranged for an introduction to the managing editor of the Morning Chronicle, and dined cheerful at the Hotel Gorgonzola y Vino, which is so expensive that patrons try to slip by the hat boy without claiming their coats at all. He attended the new musical review, Can You Beat It, Bo? and applauded, not like a soul recently called to the finer life, but like a buyer who had come on without The Wife.

At midnight, very pink and cheerful and brisk, with a carnation in his buttonhole and a stick swinging, all as glossy and luxurious as the orange back of a new ten dollar bill, Mr. Brown arrived at the office of the Morning Chronicle, and talked to the managing editor for ten minutes. He wanted, he said, to hire a good press agent, and a man who could think up plots for stories but was too lazy to write them.

For the publicity, the editor suggested Bill Hupp, who had been press agent for the Vampire Film Company till the recent consolidation. As to plots, there was Oliver Jasselby, who was always so exhausted by telling what genius his plots showed that he never wrote a thing, and had to hold down a job on the Plumbers’ Gazette.

At seven in the morning, Mr. Brown rose to lead the life literary, and get it over. He telephoned to Bill Hupp and Oliver Jasselby to come to his hotel at nine. He hustled out, and before the real estate offices were open he had routed out the superintendents of three buildings, examined seven offices, and engaged one. He dashed by taxi to a shop on Third Avenue which rents secondhand office equipment, and hired desks, chairs, rugs and a dictation machine. He bought carbon paper, typewriter ribbons, boxes of paper.

At nine he was prancing up and down his hotel room, planning a poem. Bill Hupp, the press agent, was announced at nine-one.

Mr. Hupp was built on the general lines of a motor van. He loomed into the room, glanced at Mr. Brown, chucked his yellow chamois gloves and fur coat on the bed, cocked his long ivory cigarette holder NW by N, two points N, and boomed “Well, what’s the sordid task? What am I to perpetrate on the public prints? Nice line about having organized a League for the Prevention of Cruelty to the Heathen, or just plain case of breaking into society?”

“Neither. I want to be a literary genius.”

“My Gawd, you don’t want me. I can’t help you. I’m a press agent, not a bartender.”

“Sure. I savvy. I guess the game is bunk. But I’ve got a girl who is artistic, and I got to follow suit, see? Me, I’m a lumber merchant. I never wrote anything in my life but ads and letters.”

“Got ye. We’ll put you across. I’m engaged. Salary, one hundred a week, and all we can drag down from the padded expense account. Name’s Bill Hupp.”

“All right. Now I want you to put me on to the very latest styles in literature. I don’t want to waste time on anything that isn’t dead highbrow.”

“Sure. Well, first, there’s this vers libre.”

“Huh?”

“Why, vers libre — free verse — so called because it doesn’t pay. It’s choppy stuff with no rimes or rhythm. Walt Whitman in kid gloves. You’ve seen it — this kind of poetry that you wouldn’t know it was poetry if it wasn’t printed that way. Then there’s these one-act plays for little theaters, like the Hobohemian Players. The plays have either got to be gruesome — cheery little jamborees, like a murder in a morgue — or else highbrow kidding stuff taking off all the playwright’s friends down in Greenwich Village. Third, there’s Russian realistic novels. That’s all.”

“Fine, Bill. Here’s your first week’s salary. Say, can you buy me about twenty-five dollars’ worth of samples of all this stuff, so we can model our own lines after them?”

“Right, boss.”

Oliver Jasselby did not float in till ten. Mr. Jasselby, the plot-hound, was a small little man with sandy hair and eyeglasses on a silk ribbon. He bubbled and squeaked when he talked. He agreed to deliver weekly at the office the following raw materials: One novel plot, four short story plots, six ideas for vers libre, and one outline for a morbid play.

When Bill Hupp returned with a consignment of the latest novelties in high art, Mr. Brown and he planned the first publicity. Bill suggested that Mr. Brown’s first name be temporarily changed from Dennis to Denis. The newspapers were to be permitted to run modest notes to the effect that Denis Brown, the distinguished California poet and dramatist, had come to New York to live. Not that Mr. Brown did come from California, but California is a good safe place for geniuses, climate and election returns to come from.

When Bill had gone off to supervise the furnishing of their new office Mr. Brown waded into the sample literature. By twelve, he believed that he had mastered the mechanism of the three forms of art.

He saw that vers libre was exactly like advertising, except that usually it was not so well done. The rules were the same — short snappy stuff, breaking away from old phrases, getting a unified impression. Now Mr. Brown had written advertisements. He remembered his masterpiece: “Who, is the bugaboo man who flags you every time you dream of the Little Cottage for Two? It’s your local builder! Let us bully him for you, soz you’ll get what you want, old top! Buy an Inland Portable Bungalow — you can clamp your eyes on it first, and know you’re getting what you wanta get — not what Mr. Local Builder thinks you think you want. Then it’s ho! for the Little House o’ Dreams among the trees, with You and Her sitting out on the 10 by 22 porch in the good old twilight dreamtime.”

When he had completed this advertisement, two years before, Mr. Brown had been rendered violently ill by it. But it really had sold bungalows, and now he perceived that it had in it most of the essentials of these poems about colors and twilight and mist and young women.

As regards the little plays for little theaters, he decided that they were exactly like smoking-car stories, related with gestures and snickers — except, perhaps, that the smoking-car stories were more moral.

And the final gasp in recent art, the Russian realistic novels, resembled the detailed reports on lumber-tract conditions which Mr. Brown had made for lumber companies in his early days. There was the same serious attention to dull details, the same heaviness of style, and the same pessimism about the writer’s salary.

Mr. Brown chortled.

“It’s just as I guessed. The reason why these guys get away with literature is because no business man has taken the trouble to go in and buck them. Oh, it’s a shame to take the money.” He telephoned to Bill Hupp, at the office. “Say, Bill, if you don’t mind, will you start sneaking in some press stuff about a Russian realistic novelist named Zuprushin?”

“Who’s he?”

“He ain’t yet. But he will be.”

“Then how do I get any dope about him?”

“He’s planning to come over here. His novels are being translated into English. He’s an immoral old hound. Primeval brute. His latest novel is a cheery thing called Dementia.”

“I get him. But what’s the idea?”

“We’ll write his novels for him. Bill, you listen to me: Inside of two months we’ll have every highbrow in New York talking about Zuprushin. From what you tell me, these New York littery gents don’t have time to read any of these foreign authors — they’re too busy talking about them. They don’t even buy the books. That’s done by the nice little old maids that overhear the talk. So the highbrows won’t dare to let on they haven’t heard of any new literary joker, and once we familiarize them with Brer Zuprushin’s name, they’ll all talk about him.”

“Yes, but say, boss — Hello! Hello! Get — off — the — wire — willyuh, operator! But say, boss, what’s the use of creating this Cossack cockroach?”

“Why, when he’s going big I’ll tell my girl I invented him, and she’ll know I’m the family genius.”

“Gotcha.”

Mr. Brown went out, humming. In four hours and a half he had made a scholarly study of all literature, created the poet-dramatist Denis Brown, and gently guided that unfortunate child of genius, Zuprushin, through his boyhood, studenthood, and the writing of his novel Dementia. For a person who had not been a literary gentleman till seven o’clock that morning, Mr. Brown felt that he was not doing badly, and he was whistling loudly when he arrived at Ysetta’s flat for tea.

III

Ysetta’s flat, on Morningside Heights, was a somewhat arty abode. There were curtains and a couch cover of gunny sacking, seven brass jars which held nothing in particular, candles which lighted nothing at all, and a near-silver percolator which was out of order.

Ysetta received him with marked calm. “So you are here!” she surmised by way of greeting.

“Me? Where? Why no; I can’t be here, can I, honey? Why, I’m just a little old bourgeois from Northernapolis.”

“Please don’t be so boisterous, Dennis. I suppose you are finding your business trip very amusing.”

“I’ll tell you about that later. First, you’ll want to know the news about Mrs. Fliff and Mrs. Smoot and Mr. — ”

“No, I can’t say I do!”

“Huh?”

“Poor earnest souls — it’s amusing to think of them trying to write.”

“Why, gee whiz, Ysetta, I thought you said they were such ink-pitchers?”

“Did I? Would you like lemon or cream in your tea?”

Mr. Dennis Brown had been thinking up a neat line on the subway, and he had his cue. He looked her over cynically. He smiled and pinched his lips.

Ysetta frowned, and roused from her Olympian ennui to demand: “What is it you find so amusing?”

“You, my child. It tickles me to hear all you highbrows use the word ‘amusing’ for everything from Mrs. Fliff to yellow vases with black spots.”

“How amus — How pleasant it must be to be tickled,” she sniffed.

But she didn’t seem quite so sure of herself.

“The other thing is: I wonder how you can be so banal as to say ‘lemon or cream in your tea?’ I suppose that at the present second more than forty thousand poor bourgeois females are saying just that.”

Ysetta completely forgot her superior attitude, and yelped “Oh, you do, do you!” in a manner which recalled the days when young Dennis Brown had pulled the hair of the little girl, Elizabeth Robinson.

“Yes, I’m sorry for you. But, of course, with this frightful handicap of coming from west of Chicago, you couldn’t expect — ”

“Then you may be pleased to know, my dear Mr. Brown, that I have had a vers libre — if you know what that is! — accepted by Direct Action, the one big, bold, free magazine in America!”

“That’s bully! It happens that I have just had a vers libre accepted by Direct Action, also!”

“I don’t think it’s very nice of you to joke about it. I think you might congratulate me.”

Ysetta spoke plaintively. Again there was more than a hint of the little girl from Northernapolis.

“No, seriously, hon, I mean it. You see, the deals that brought me to New York aren’t deals in lumber, but in ideas! Since you left Northernapolis I have felt the call of literature, too, and I have come here to learn. Humbly. Though I must say that the editor of Direct Action swore my poem was the finest he had ever seen.”

“Hon-est-lee? Oh, what is its title?”

“ Its — Oh! Oh, I see; you want to know its title.”

“Yes.”

“Why — uh — why, its title is ‘The Color of Thought.’”

“Why, that’s a wonderful title! Oh, Dennis dear, I can’t tell you how excited I am that you have seen how heavenly New York is. I’m still bewildered by it, but I’m so glad! Come down and hear the Hobohemian Players with me tonight, and meet Mrs. Saffron.”

“Hoozis? Mrs. Saffron that writes all this Woman-Can-the-Shekels — I mean Shackles — stuff?”

“Yes. She is the leader of the fight for woman’s freedom. And such fire! Such wit!”

“Gladmeeter.”

“Come for me at seven. And now tell me about those funny pathetic old hexes at the Short Story Club. I wonder if I ever told you about a terribly amusing story called “Dora of the Redwoods” that Mrs. Fliff wrote? I’ll never forget it. Even you would have writhed over it.”

“Yes, maybe I would,” he said a little wearily.

He perceived that he was going to have something of a task in keeping pace with Ysetta in his new occupation of forgetting that there was such a place as Northernapolis, where the benighted people did their work and went home at night to play with the kids, instead of leading the life literary. But he escaped without committing that worst of social errors — saying what he thought.

Between five and seven he had to have “The Color of Thought” accepted by Direct Action. Also, incidentally, he had to have the same written. For he had not exactly lied about the poem, he had merely sold short.

He sat down on the steps of Ysetta’s apartment house and did a job of thinking. It may be that his thoughts did not have the fire and glory which fill the meditations of all regular licensed public authors, but he did get down to business.

He had chosen the title because he had noted that color was a favorite theme in vers libre. Now he had to get some attractive new hues. He dashed to the subway news stand and bought a fashion magazine. On the subway he read the descriptions of new gowns, and encountered the color words “taupe” and “beige.” Mr. Brown did not know whether taupe was a watery pea-green, or a pink resembling the ears of a rabbit, and he did not care. On the margins of the magazine he wrote his poem. Between the subway and his hotel he stopped in at a jewelry shop and inquired for the name of a gem “that most people don’t know much about.” The clerk suggested “chrysoprase.” With that word Mr. Brown filled a space in one line of his poem. At the hotel he hastily dictated the poem to a stenographer. The completed product was as follows:

THE COLOR OF THOUGHT

Red that is blood —

Blue, soggy with the sky —

Green of the hackneyed spring —

Me, I hate these raw old colors, and I hate

White of dull purity,

But!

Taupe and the mystery of beige,

Colors inarticulate, moving, twisting, blind,

And color of a seadrowned chrysoprase —

These are the hues of thought,

Cruel,

Dread,

Power!

He expected to have to trace the editor of Direct Action from his office to some abode of rum and anarchism, but by telephone he found him at the office. He arrived there in seven minutes, two of which were spent in an impassioned debate between his taxi driver and a traffic cop.

He bounced into the office of Direct Action and beheld a young man writing at a small table which was so surrounded by piles of realistic novels, vegetarian pamphlets, pacifist manifestoes, bills advertising socialist dances, and suffrage banners, that it resembled a trawler in the midst of the British fleet. The young man looked up wearily.

“Brother, I want to see the editor.”

“Comrade, he is me. It’s after hours, but what can I do for you?”

“Shall I make Congress pass your bill, or shall I expose the governor, or do you merely want to sell me a story at three cents a word?”

“Brother, I suspect that you are a regular guy. It is none of them things. I would fain subscribe to your sheet, which I have never seen a copy of; and while you are recovering, I would still fainer get you to accept this poem in vers libre, and you don’t have to pay for it. I just want to see it printed. Honest, it isn’t as bad as some I’ve read.”

“Comrade, let’s gaze upon it — and hurry up with the introduction.”

“Brother, I don’t get you.”

“Why, the introduction; the spiel about your deep inner meaning in writing it — about its being vorticist verse, or a fugue in words, or whatever it is that distinguishes you from the ordinary apprentices.”

“Brother, there ain’t a darn thing that distinguishes me!”

The editor thrust the poem, unread, into a pigeonhole marked “Copy ready for printer.”

“In that case,” he said, “I accept it. Either it will be so good it’s worth printing, or so bad that my readers will think it’s some new brand of genius. Comrade, my name is Jerry McCabe, and when I gaze on your sprightly young face I suspect that you are a good guy. But don’t let that make you forget those dulcet murmurs about subscribing.”

Denis Brown, poet, arrived at Ysetta’s house only ten minutes late, which meant that he had to wait in the lower hall for twenty minutes. She appeared, in a clinging gown of green silk with a border of orange stenciling, and insisted:

“Dennis, you were joking about having a poem accepted by Direct Action! Why, I bet you can’t even tell the name of the editor!”

“Why, Jerry McCabe, of course! By the way, old Jer may be down at the Hobohemian Players tonight too.”

“Well, I don’t understand it. You only arrived in town yesterday,” said Ysetta with a restlessness not unnatural in one who has just been emancipated, and discovers that her home town has been sneaky enough to go and get emancipated also.

IV

They had dined at the Cunning Rabbit Tea Shop, Mr. Brown and Ysetta, and had witnessed four one-act plays presented by the Hobohemian Players.

Everybody in New York is always delivering something from some shackles, and the Hobohemian Players are an organization for delivering the stage from the shackles of the commercialized managers, and for developing a Native American Drama. Tonight the Players presented Native American Dramas translated from the Polish, the Siamese and the Esquimo, and one apologetic little curtain-raiser written in the United States.

Mr. Brown didn’t care much for the plays or the acting; and the audience, which kept telling itself between acts how superior it was to Broadway audiences, made him feel feeble; but aside from that, he enjoyed the show; and afterward he obediently tagged after Ysetta to meet Mrs. Saffron and her group at the Café Liberté.

Ysetta warned him:

“Now, Dennis, I want you to be careful what you say to these people — they are so clever and subtle and all — and don’t get off any of the noisy jokes you used to in Northernapolis. I’m as careful as can be what I say, till I’m admitted into their inner circle, and you — ”

As Ysetta expressed her timid admiration for Mrs. Saffron, her books on eugenics, and her participation in clothing strikes; for Max Pincus, the landscapist, Jandorff Fish and Gaston Rakowsky, the novelists, and Miss Abigail Manx, the anarchist queen, Mr. Brown became nervous.

With the feeling of a small boy on his first day at a new school, he followed Ysetta into the basement of the Café Liberté. It was only a fair-to-medium basement; Mr. Brown owned as good a basement himself, in the family mansion. It was painted a plain tan, and filled with chairs and tables that looked much like other chairs and tables. But the people were terrifying. When he could make out the individuals, through the confusion of talk that sounded like a phonograph factory next to a recreation park, Mr. Brown decided that Hobohemia was not going to be easy. There were large, bland, round-faced young men, with an air of inexpressible superciliousness. Two lads in evening clothes were being humble to a dismayingly pretty girl with bobbed hair, who laughed at them and made love to a stolid hulk of a man with a dark face, weedy blue-black hair, and a mustache so much like one whole live cat that it might at any moment have been expected to fly across the room and out of a window. Seven nonchalant and good-looking women were dining together, and they looked him over till he felt shredded. Behind them were babbling millions.

“Some bunch!” said Mr. Brown weakly.

“Oh, these are just imitations — society slummers, and artists that are as disgustingly respectable as though they were merchants. The real Greenwich Villagers always go in the next room.”

“Well, let’s stay here in the compression chamber a minute and get used to the air pressure before we try the real wild ones,” he begged, but she pushed through into an inner room. Round the table in the center were a dozen people, who bawled at her:

“Bonsoir, Ysette. Join us!”

Mr. Brown was conscious that they were all giving him what in less spiritual surroundings might have been called “the once-over.” He timorously sat down between Ysetta and a stern, smooth, tailor-made woman of thirty-five to forty. She was introduced to him as Mrs. Saffron.

Mr. Brown had expected Mrs. Saffron to be a wild-haired bouncer in a smock. He was rather uncomfortable in the presence of her mannish efficiency. A chinless redhaired young man dropped into the seat on the other side of Mrs. Saffron, and bawled at her in a raw prairie voice:

“How are you, honey? What you drinking?”

Mrs. Saffron turned her back on Mr. Brown, and he was left alone, a child in the dark. On one side of him Ysetta was talking to Max Pincus, the painter, a short, solid young man with a heavy and pasty face. Mr. Brown instantly developed a considerable degree of dislike for Mr. Pincus. who did not talk of landscapes but of Sex, with a capital S and four exclamation points after the word. In his rolling voice Mr. Pincus was assuring Ysetta that free love was the only possible life for a genius. Ysetta was attending meekly, and smiling — with the clear chestnut eyes that Mr. Brown loved — into Mr. Pincus’ glistening little eyes.

On the other side Mrs. Saffron was permitting the red-haired person to make violent love to her. She chuckled at him, and yawned “Oh, go home, you baby; you make me tired”; but she let him hold her hand and assure her that she was the only one in the world who encouraged him to keep up his artistic photography.

Jerry McCabe, the editor of Direct Action, came by and bent over to whisper to Mr. Brown: “I condole with you.”

“Say, McCabe, how do I get on the inside with this bunch of intellectual giants?”

“Make love to Mrs. Saffron. Watch Red. He does it badly and promiscuously, yet it suffices to keep him in the foreground.”

Two minutes after, when Red had departed, Mr. Brown leaned confidentially toward Mrs. Saffron and crooned just as though she were not a radical leader:

“Honey, I could slay our young friend for monopolizing you. Why do you think I came here? To see you!”

Mrs. Saffron didn’t seem in the least indignant.

“Well, you do see me, don’t you?” she replied affably.

Whereupon Mr. Brown forgot that he was to be modestly retiring, and with a high percentage of perjury informed Mrs. Saffron that she was fair to gaze upon and charming to talk to, that her revolutionary efforts were the one thing that inspired him in his poetry, that he wanted to buy her some more drinks and lots more cigarettes, and that he didn’t care a hang who saw them holding hands under the table.

Ysetta, who had been ignoring Mr. Brown, began to notice that he seemed to be able to get along with the lofty Mrs. Saffron. Then she discovered that the whole table listened to Mr. Brown when he told about the latest Russian novelist, Zuprushin, and his novel Dementia. She amazedly saw that Mrs. Saffron was urgently introducing her “nice boy,” Mr. Brown, to the other nice boys, Jandorff Fish and Gaston Rakowsky, who listened feverishly as Mr. Brown outlined the plot of Dementia, which, apparently, had recently been translated from Russian into French.

The unlettered business man demanded fiercely of the master novelist, Jandorff Fish — temporarily employed by an interior decorator:

“Why, surely you’ve heard of Zuprushin?”

“Certainly I have! In fact I have one of his books at home, in French, though I haven’t got to it yet.”

Abigail Manx, who had joined the bunch without invitation, declared:

“Of course Zuprushin is superior to any American writer, but he doesn’t compare with Artzibashef, or even Andreyeff.”

Max Pincus deserted Ysetta to get on the bandwagon.

“Nonsense, nonsense!” he roared. “Mr. — Your friend, Ysetta, iss right. Zuprushin is the ver’ latest manifestation of the somber Russian soul!”

“I told you so!” exclaimed Mr. Brown. “Look, Pincus: you’ve read your Zuprushin in the original, while the rest of us only know him in French. Don’t you think that Dementia is infinitely more — oh, you know.”

“Oh, yaas!”

“But Gray — Zuprushin’s new novel, Gray — the one that hasn’t been translated from the Russian yet — can you tell me about it?”

Though he was rather vague about the plot and characters of Gray, Mr. Max Pincus gave a discourse on its “vital motivation” which really did him credit, considering that Zuprushin was now only about twelve hours old.

When Mr. Pincus had turned again to Ysetta, and Jandorff Fish and Abigail Manx had sunk into a bitter wrangle as to the reason why there were no Zuprushins in poor sodden America, Mr. Brown went the verbal rounds of the rest of the table, and one by one he asked the yearners whether they were good little radicals and knew their Zuprushin. They did, oh, indeed they did!

Again Mr. Brown indicated to Mrs. Saffron that he was desirous of buying her a fresh box of cigarettes and a lot more drinks, that if they two could get rid of all these Little People they would stride across the mountains together, and that he cared less than ever who saw them holding hands. To which Mrs. Saffron listened with mockery and delight.

Max Pincus, fulfilling the onerous duties of genius, had to go over to another table and make love to some girls who had just come in. Ysetta was left stranded. She turned to Mr. Brown with more interest than he had seen for many months. But he paid no attention to her. He wanted her to be just a little jealous, and —

And he was surprised to find that he was actually enjoying making love to Mrs. Saffron. Although she devoured his compliments raw he was none too sure that she was not thoroughly on, and in the game of trying to find out what she thought he was not excited by Ysetta’s naïve tactics. When the Liberté closed for the night Mrs. Saffron was telling him the story of her life — at least one version of the story.

The Hobohemians stood unhappily on the sidewalk — exiles with no smoky place to go, though it was only one o’clock and the talk just beginning to get interesting.

“All of you come over to my place!” cried Mrs. Saffron.

“Shall I come?” Ysetta asked timidly.

“Oh, you — you most of all funny little child from the West!” purred Mrs. Saffron. But as she looked over Ysetta’s shoulder into the eyes of Mr. Brown her expression indicated that it wasn’t Ysetta she liked best of all.

Though the socks-trade strike and the Dakota mine strike had both been planned there, Mrs. Saffron’s flat was not exciting, except that pillows were used in place of chairs. The talk faltered. There were only eleven people there, instead of the jolly crowd at the Liberté, and they discussed scarcely any subjects except the war, sex, Zuprushin, Mr. Max Pincus’ paintings, birth control, eugenics, psychoanalysis, the Hobohemian Players, biological research, Nona Barnes’ new way of dressing her hair, sex, H. G. Wells, the lowness of the popular magazines, Zuprushin, Mr. Max Pincus’ poetry, and a few new aspects of sex. So the party broke up as early as two-thirty, and they all went home to get a good night’s sleep for a change.

Mrs. Saffron had invited Mr. Brown to come in for tea, and bring “your nice little friend, Ysetta.”

Ysetta had overheard this, and after a strained silence in the taxi on the way home, she observed:

“Dennis, do you know that you forced your attention on Mrs. Saffron to such an extent that one would almost have thought it was you that took me to the Liberté! And you promised to be so careful. What were you talking to her about anyway?”

“Oh, about Zuprushin.”

“Well. . . . Well, I must read some more Zuprushin too. . . . When I get the time. . . .”

“Sure.”

Mr. Brown grinned in the darkness. But he was in a turmoil, whereof these were the component parts:

Three hours of mixed drinks and cigarette smoke.

A feeling that Ysetta would have to be thoroughly spanked.

A feeling that he ought to feel that Mrs. Saffron was a crank, but —

A feeling that he would jolly well like to know whether she really liked him or was merely having a good time with him.

V

The office of the D. J. Brown Literary Productions Company, in the Knee Pants and Overalls Building, on aristocratic Fifth Avenue, was in full activity. Bill Hupp was busy with the telephone, getting little notes about Zuprushin and Denis Brown, the poet, into all sorts of publications, from the New York papers to the Zoölogical Quarterly Review. The stenographer was on the jump, with manuscript copying, and letters to editors. Oliver Jasselby arrived weekly with children of the brain which were to be incubated by the Productions Company. Mr. Brown supervised everything, and when he had time actually did some writing. In the morning he devoted himself to vers libre and one-act plays; in the afternoon he turned out short stories and a novel for M. Zuprushin.

The Zuprushin brand rapidly became their chief line of manufacture. The verse of Denis Brown didn’t sell very well, and it attracted no attention, while the readers for the Hobohemian Players and the Cockatoo Theater turned down all his plays. His name wasn’t foreign enough! But Zuprushin was so popular with the radical magazines that after the publication of his two stories, “The Faun of Folly,” and “Fog of the Samovar,” in Direct Action, his American agents, Messrs. Brown and Hupp, received dozens of letters from small but fiercely iconoclastic magazines asking for contributions.

There may be a wonder as to how Mr. Brown, of the Inland Lumber Company, could write the stories of M. Zuprushin of Moscow.

Efficiency, always efficiency.

First, he would secure a thoroughly disagreeable plot from Mr. Oliver Jasselby. Then he would think of the meanest possible character. He preferred a gentleman who was the descendant of a prince with paralysis and a gypsy with kleptomania. By preference the lad suffered from vodka, carcinoma, neurosis, Anglomania, vegetarianism, cocaine and artistic vision. He killed his baby sister because she insisted on playing with dolls, which he regarded as a weakness unworthy of the Great Russian Gloom. Whenever he gave the toast “The ladies, God bless ‘em!” he always made a slight change in the verb.

Mr. Brown would sit and brood about this hero till he hated him ferociously, then dictate a lucid but not necessarily polished account of him, occasionally referring to Mr. Jasselby’s plot for suggestions as to what the lively spalpeen could do next. As Mr. Brown’s knowledge of Russian daily life was comparatively slight, except for having once sold an old suit to a Russian Jew in Northernapolis — an incident which had caused him to distrust the whole Tartar race — he wisely laid the scenes of his stories in Northernapolis or New York.

He shipped the product in to Mr. Bill Hupp, who had once been on a newspaper copy-desk and was qualified to put in the adjectives, the spelling and the punctuation. Then it was routed to the latest member of the staff, Mr. Mischa Knippensky. Mr. Knippensky was a slender, sallow, bad-tempered young man who worked on a Russian weekly.

He inserted the Russian names and local color, and a few jolts of pessimism carefully culled from Pryzbyszewski, Artzibashef, and Dostoieffsky.

When the masterpiece left Mr. Brown’s own hands it would read thus:

“This fellow John Henry is sitting in his room and he looks out at the mist rising from Muskrat Creek and thinks the creek is getting low, the banks are so muddy, just then a Twin-Two car goes up Main Street past his window and turns onto Floral Avenue and stops in front of the Hartford Lunch. John Henry says, Gee, I don’t hardly know whether that is an automobile or my heart pounding, I got to stop smoking so much, now wouldn’t I look like a boob dying of smoker’s heart when I could get more publicity by croaking myself or pinching a horse and getting shot up by a deputy. I guess maybe I wouldn’t mind kicking off by biting J. Edwin Bindle and getting hung. Just then Gwendolyn De Vere trots into the room. ‘I made a getaway after all, she says, my mother is gassing with Mrs. Fliff, and I sneaked out on her.’

“John Henry kisses her, then remembers how she bores him. ‘I got to go down to the office and get out a form letter,’ he says, he grabs his top coat and just as he gets to the door she grabs his razor and cuts her wrist, it bleeds something fierce. ‘My Gosh, cries John Henry, I bet I get hung for this, probably I better commit suicide after all.’

“Memo: Bill: See what you can do along above line. It’s rotten, but you get the idea. Tell Knippensky to get in lots of the agony stuff here, and get the copy out of him before you pay another advance. D.J.B.”

After the joint efforts of Bill Hupp, Mischa Knippensky and the stenographer, the gay little paragraph would be transformed into the following:

“The room was crepuscular. A mist, vague, choking, chill as the tomb and inescapable as the burden of continued living, rose from the sluggish Neva. The hoofs of a horse racing down the Nevskii Prospekt echoed like the tick of a death-beetle. . . . Were they hoofs? Or his own heartbeats? He had been smoking too many cigarettes of Cairo, Ivan Nicholaievitch thought. He must stop smoking. . . . It would kill him else — him who was so proud, who had planned to die in some manner more dramatic, more fine and tender, than by too much smoking. . . . He forgot the sinister fingers of the fog as he treasured the superb ways in which he could die. . . . Lingering consumption, a duel, the barricades, hashish, suicide. . . . Yes, most of all, suicide. They would find his body . . . Corpse . . . Crushed, scarce recognizable . . . They would cry: ‘One of us, at least, has found something interesting to do, in this meaningless treadmill of life.’

“Polina rushed into the room. ‘I have come to you!’ she cried. ‘My husband sits sodden with a decanter of vodka before him. I gave him the vodka, the dear little father vodka.’ Ivan Nicholaievitch kissed her violently. ‘You are so strong, so brutal, so wonderful, Ivan Nicholaievitch,’ she said. He put on his caftan, started for the door. ‘Why do you leave me?’ she groaned. ‘You smother me,’ he said. ‘I was in the midst of a speculation which would have solved all the restless quest of this transitional age.’

“Polina took from the table his little pistol and quietly shot herself. He looked at her. ‘She really is dying,’ he marveled. Though that strange gentle soul of his was ruffled by her utter thoughtlessness, he added no word of blame. He sighed, ‘And it was such a little pistol. I would not have thought it would have killed her so dead. . . . It is time to go down to the barracks, and flay a soldier. To keep up discipline. . . . Is it not humorous that one should keep up discipline now, when the question that would console all noble beings for having to live is wavering in solution in my mind — hanging or suicide — a splendid hanging, under the fresh morning clouds, kicking at the banal sky in an ecstasy of torture — or suicide at midnight, alone, palsied by the funereal fog of Mother Neva?’ Ivan Nicholaievitch went sadly out and closed the door. . . . Polina bled a good deal, but presently she was dead. . . . Quite dead. . . . In the kitchen Genitchka could be heard shucking an onion and grumbling that the milk had curdled.”

VI

Though the tales of that grand old fake author, M. Zuprushin, revealing the somber hinterlands of the Slavonic temperament, issued from it, yet the office of the D. J. Brown Literary Productions Company was not scary, as ordinary readers of Zuprushin might have imagined. Mr. Brown and Bill Hupp worked at large roll top desks; they wore green eye shades and silk shirts and long cigars; they yelped excitedly “Landed an item in the Literary Review, Denny”; or, “Gosh, Bill, I got a humdinger of a detail for the hero of ‘Mute Madness.’ You know where he kills his grandmother? I’m going to have him chew a strand of her blood-stained hair and whisper ‘It tastes gritty.’ Class, what?”

Mr. Brown was used to the bustle of an office, to telephone bells and typewriters and the bang of elevator doors, and the activity of his new establishment was an inspiration to him. Whenever he desired to describe the vast solid silence of the steppes, he went out and listened to the stenographer pounding his machine and whistling The Honey-hu-hu Rag.

The stories of Zuprushin in the magazines, and the mention of his coming novel, Dementia, in the literary columns, were seriously received. Mr. Brown heard comments on them every time he went to the Café Liberté, to Mrs. Saffron’s or to Ysetta’s. He would in a very few weeks be able to tell Ysetta the truth, and take her back to Northernapolis without being spiritually henpecked.

There was only one trouble in regard to Zuprushin. He had no one theory of life which the Hobohemians could grasp and talk about. Something could be done along the line of feminism. You could always get a hearing in Hobohemia by discovering a new way of repeating that women were the equals of men. Then why not declare that women were the superiors?

You who daily hear of the theory of katanthropos will scarce believe it, but it originated in the mind of Mr. Brown, lumberman, and was fully developed by him after reading two articles on biology in the cyclopedia, and asking Mischa Knippensky, translator and scholar, for a couple of good snappy Greek words.

Katanthropos means that men are to women what drones are to the worker bees. It is derived from the Greek “kata,” meaning “down,” and “anthropos” meaning man — and as the two words together don’t mean anything in particular, they have enormously puzzled the college professors, who have explained the combination in nine-page articles ballasted with footnotes. I now reveal the truth, which is that “katanthropos” was Mr. Brown’s simple-hearted translation of “Down with the men.”

In two stories in Direct Action, Mr. Zuprushin used the word “katanthropos,” and in an article in Psycho he came out flatfooted and said what he thought about katanthropos. He pointed out that among the lower animals, though the males might be showier than the females, they were merely parasites; and he suggested, with that powerful irony of his, that in our own human experience men certainly are the most complete dubs that can be imagined, and, therefore, women must be better.

Aside from being old as the hills, and biologically incorrect, katanthropos was really a nice new theory. All of Hobohemia instantly began to talk about it. It almost wiped out psychoanalysis and sex inhibitions as the popular topics for discussion at the Liberté. Mr. Brown himself couldn’t keep up with the latest twists given to it. If he sat with Ysetta at a table for two at the Liberté Max Pincus would come darkly lumbering in, drag another chair up to their table, demand that Mr. Brown buy him a drink, make love to Ysetta, then plunge into a monologue on katanthropos.

Mr. Pincus didn’t exactly say so, but he let it be inferred that long before Zuprushin had been heard of in America he, Max, had met him in Little Russia and heard all about katanthropos from the lips of the Master — sure, Max called him “the Master.”

Mr. Brown was really impressed on the evening when Gaston Rakowsky informed the group that all of five years before he had talked over katanthropos with Herr Professor Dr. Hans Heinrich Wukadinovitch, of the University of Bonn.

Mr. Brown was grateful to them for helping him to lay the groundwork for a good paying. business. Meantime, he was getting into literary society. He found that all he had to do was to be around, and he would be invited to at least nine parties a week. Some agitated lady, with back hair that ought to have been subjected to universal training, was always getting up a studio party, and wildly looking for guests, and inviting whole tablefuls.

He found that he could not keep up with his literary social engagements. The Liberté group was only the beginning. There were at least three hundred distinct artistic groups in town.

There were crystal ball and table-tipping parties at large bare studios in uptown loft buildings; teas in duplex apartments near Central Park; anarchist songfests in cellars on Mulberry Street; “quaint” restaurants on Washington Square, where social workers and writers went for dinner; lunch clubs of young editors and writers and artists, who disapproved of the Liberté, and talked solemnly about the publishing business; dinner clubs composed of ex-soldiers of fortune who wrote tales of adventure; poker parties at which literary but raucous young men drank growlers of beer; a social set frequently attended by dowagers with lorgnons; and even a commuting literary set, which would invite you to weekends. All he had to do was to be at one party, and he was asked to nine others. So that the last state of that man became a lot worse than the first; and Mr. Brown’s notion of a real entertainment was to go home, play his own records on his own phonograph for half an hour and go to bed.

He met almost every well-known writer and artist in America — and the sight considerably saddened him. He got used to asking “Who’s that meechin’ jack rabbit of a man over there drinking tea with his chin and talking about his lumbago?” and hearing the horrified reply: “Why, that’s the most famous writer of cow-puncher stories in America!”

Sometime during these social explorations Mr. Brown discovered that Ysetta was becoming interested in him — and that he wasn’t quite sure that he was still in love with Ysetta. Ysetta had too much Northernapolis air in her system to get herself ever really to like the thick-lipped, blue-faced fervidness of Max Pincus. She was always a little bewildered at the Liberté. Once Mr. Brown became a favorite and an insider, she began to admire him. She assumed that they two had been comrades in the fight for Culture back in poor Northernapolis.

Mr. Brown should have been gratified. But, like every business man, he was excited by pushing through a deal; and now he was interested in the game of literary success for its own sake. At first he had gone to parties only to see Ysetta; now she was not present at half the gatherings he frequented, and he called her up for tea only once a week.

So she began to telephone him, to implore him to take her for walks in the country. She began to call him “Big brother” whenever there was moonlight, and to sigh contentedly if he held her hand. When he informed her that M. Zuprushin had read one of his free verses and had actually written to him — he showed her the letter, which was in Mischa Knippensky’s very best French — Ysetta almost kissed him. But he did not notice her intention. At that moment he was engaged in thinking “Time to beat it — due at Jane Saffron’s.”

For in the midst of his social rush he managed to see Mrs. Saffron at least three times a week. Whenever he thought Mrs. Saffron was in love with him, she would laugh at him; whenever he thought he bored her, Mrs. Saffron would whisper:

“Denny, dear, I need you near me this evening. These boys of twenty-five, with their theories, are so old. But you have the heart of eternal youth and daring. I suspect you of having been a gallant soldier.”

It is yet to be discovered that the firmest pacifist objects to being told that he has been mistaken for a gallant soldier, or that the most solid business man finds anything ridiculous in the statement that he has a heart of eternal youth. Mr. Brown could always be depended on for tea at Mrs. Saffron’s.

He may have dreamed of Ysetta’s pale pure face, framed in an oval by her corn-colored hair, but that does not imply that he still desired to be her private worm, ready to be trod upon at all hours. He was beginning to feel that he, too, was a person with a soul, and that he would free the same or bust something.

At which dangerous period in the history of Mr. Brown’s soul, was published Dementia, the first complete novel of Zuprushin.

VII

So far, Zuprushin’s message of Katanthropos and Gloom had been known only to the hardy thinkers of the cigarette belt. Now it was to be revealed to the whole hungry land. Dementia, by Serge Zuprushin, translated from the Russian by Mischa Knippensky, had been completed, accepted by a revolutionary publisher who had four times been pinched upon complaint of the Worchester Purity Society, and was now to be issued.

The newspaper world was prepared in advance. Mr. Brown and Bill Hupp had gone down to the East Side, picked out one Moe Witzig, a prophetic-looking Russian Jewish ol’ do’ man with a long black beard and an epileptic derby, kidnaped him, disinfected him, photographed him and released him in a state of wealth and bewilderment. Moe Witzig was a respectable kosher man who read nothing but Vorwaerts, and he might have been astonished to learn that in every newspaper and magazine art room in America was his picture, labeled “Serge Zuprushin, the most startlingly pessimistic of Russian novelists.”

Dementia, as published, wasn’t exciting to behold. It had a gray-blue cover, and a bilious frontispiece presenting a large unkind gentleman staring at a young woman in a painter’s smock. But the jacket was a striking thing in green and crimson, announcing that Dementia was not a book for children or old-fashioned moralists, but that it was “shot through and through with a brilliant and perilous genius.”

The advertisements also murmured modestly that it was shot through and through with this brilliant genius; and two weeks after publication, when the reviews began to come in, there was the strangest coincidence — one which shows the solidarity of thought in our land. Thirty-six out of fifty reviews asserted that while Dementia was not a book “for children or old-fashioned moralists” it certainly was shot through and through with that same kind of projectile.

In a month the real critical articles, by college professors, were appearing. Mr. Brown was slightly dazed to find out what a genius he must be. He was more dazed when he read a disquisition by James Jouse, the celebrated British novelist who had left England during the war because he felt that the British were becoming almost prejudiced against his friends the Germans. Mr. Jouse made a few scornful references to the poor American boobs who dared to criticize the titanic personality of Zuprushin, and told chattily about meeting Zuprushin in Paris. Zuprushin had said to him:

“Jim, you are the only one of the blooming Britishers who can understand my philosophy, and of course no American ever will.”

Mr. Brown was pleased to find that at the end of his article Mr. James Jouse let the public right in on a letter which Zuprushin had written to Mr. Jouse all of seven years ago, before America had even heard of Zuprushin.

“Gosh, that’s a fine letter,” sighed Mr. Brown. “I don’t know where I got that line about Tartar temperament, but it sure sounds good. I’ve been plumb wasted on the Inland Lumber Company, if I wrote a letter like that seven years back.”

Far beyond the reach of the novel itself was carried the theory of katanthropos. It became the favorite word of the hour. Vaudeville teams used it, and sob-squad newspaper women asked their readers to write in what they thought about it; cartoonists began to make fun of it — to spell it “catanthropos” was always knockdown humor; ministers denounced it; a Boston women’s club defended it; a prominent antisuffragist blamed it on the suffragists, and a suffragist on the antis. Katanthropos was an easy word — once you had learned to accent it on the an and to look superior while you said it — and millions added it to their vocabularies. If a teamster’s wife in South Bend wished to convey her impression that her husband was a drunken bum, she made a sound like “you old katanthropos,” in the belief that it was a new cuss word; and if a polo player at Coronado wanted to show off before a curly-headed debutante, there was no possible means of preventing him from being witty about katanthropos.

The Zuprushin vogue began to get away from its starters.

Hundreds of women, from twenty to fifty, wrote to M. Zuprushin, care of his publisher; and Mr. Brown and Mr. Bill Hupp were dismayed as they read that every one of these women had crushed souls, and that they were using Zuprushin and his theories as excuse for eating all the candy they wanted, or deserting their husbands, or refusing to wash dishes. Messrs. Brown and Hupp were reasonably strong for suffrage, but as the diabolical word katanthropos was fired at them in scented feminine notes they began to wish to take M. Zuprushin and beat him to death.

It was Ysetta herself who finally frightened Mr. Brown. He was under the impression that Ysetta was still in love with him, as she had been for all of five weeks. He was tired, one early evening. He wanted to be quiet. With a realization that the use of the expression would have got him court-martialed for espionage, in Hobohemia, he confessed to himself that he wanted to feel “homy.” He telephoned casually to Ysetta that he was coming up.

He pictured her dear serious face — so fine and clean and keen, compared with the wallowing Pincuses and the weary Mrs. Saffron.

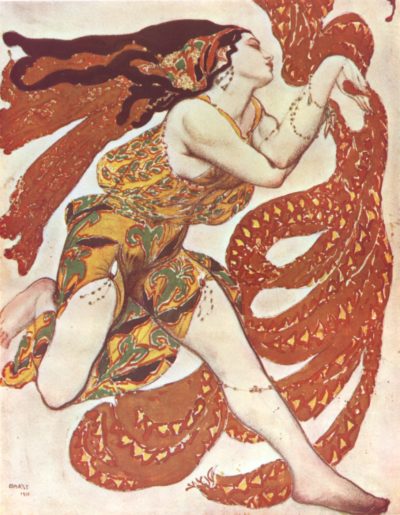

But he found Ysetta pale and abrupt and furtive. There was a change in her flat too. The picture Beethoven in Paris was gone, and in place of it hung a clever bit by Bakst, portraying a pea-green gentleman reclining beside a crimson bootjack and a delicately mauve caterpillar tractor.

“What’s trouble, Ysetta?” said Mr. Brown comfortably.

“Yes. . . . Yes, you may as well know now, and send the news back to Northernapolis, and be shocked with all the rest of your provincial neighbors and my family.”

“Why, gee, honey, I’ve canned every last shackle now. I’m as free a soul as the head waiter at the Liberté.”

“He isn’t free. He interrupts geniuses like Max Pincus to make them pay dirty, sordid, disgusting little bills.”

“Something to that. Yes, I wouldn’t call a head waiter that had as hard a job as that anything like free — ”

“And you, Dennis, despite your apparent interest in vers libre, you are at heart a Puritan.”

“Oh, no! Not that!”

“Yes! And you might just as well know that I have decided to enter into a free union with Max Pincus.”

Mr. Brown said a number of things which could not be reprinted except in a book by Zuprushin. He had learned to look calmly upon the “free union” — which means marriage to a man who is too near to get a marriage license now or a regular court divorce three years from now. But it was different to think of Ysetta in the same embarrassment. At the end of his few well-chosen remarks he classified Max Pincus as a “fat, dirty-fingered, unmanicured, hoggish, conceited, ignorant, loafing canvas-spoiler.”

“Even if I did agree with you,” said Ysetta in a bored manner which Mr. Brown recognized as an imitation of Mrs. Saffron, “I should still take Max under my wing and let his child-mind develop; because you see I have been converted to katanthropos, and I realize that, as a woman, I must control the inferior male.”

“Kat” groaned the stricken father of katanthropos.

“Yes. I have been reading Dementia, and I see what a thinly sentimental nation ours is. If I am unhappy with Max — and it may be that you are quite right in saying that he doesn’t bathe — my inner self will be developed by the splendid suffering. . . ‘Kicking at the banal sky in an ecstasy of torture.’”

“Say, for the love of Mike, do you mean to say you like that horrible Zuprushin rot?”

“My dear Dennis, your mode of expression — the elegance of your ‘love of Mike’ — excuses you from belonging to the group that can appreciate Zuprushin!”

“Now look here; you know perfectly well that I used to be one of the best little members of the Zuprushin Sewing and Conversation Circle, but I’ve come to see that the man’s plain crazy.”

“Oh, you think so, do you!” said Ysetta in a manner not entirely different from the way in which young women talk to fresh young men in Northernapolis.

Mr. Brown took a long breath. He said coldly, carefully:

“It may interest you to know that I have information from Paris that Zuprushin is a myth! A hoax! Some French journalist just faked him up!”

Ysetta neither fainted nor cried “My hero!” She changed the fingering on her cigarette and answered:

“And it may interest you to know that last night, at the Liberté, I met James Jouse — you know, the English novelist — and I heard him telling Max and Abigail that he has known Zuprushin personally for years! Oh, such a man! He says that Zuprushin drinks vodka before breakfast, and scorns all of us feeble Westerners who can’t stand manly drinks.”

“Say, look here, you aren’t trying this manly vodka before breakfast stuff, too, are you? I should almost think that was carrying your religious fervor too far.”

“No. I tried to drink some vodka once and it tasted like a sneeze. So I admire Zuprushin all the more.”

“When do you pull off this free union with dear old Max?”

“Well, I don’t know. I haven’t proposed it to him yet.”

“What d’yuh mean ‘proposed’?”

“Why, my poor Dennis, if I believe in katanthropos, naturally I shall direct both my life and his.”

It was indeed a homy evening at Ysetta’s.

VIII

Mr. Brown left Ysetta’s flat at nine-thirty to attend a conference with Bill Hupp at the office. He found Mischa Knippensky, the translator, there, unusually sallow and nervous. Mr. Brown looked at him with distaste.

“Say, Denny,” said Bill, “we got a letter from the Women’s Radical League asking us, as Zuprushin’s agents, to get him to come over to this country and lecture. They got a lot of pull too. Sort of a society anarchist bunch.”

“Nothing doing,” grumbled Mr. Brown.

Mischa Knippensky broke in:

“Yes, there is something doing.”

“What d’yuh mean?”

“I think I’ll have Zuprushin come over. Come over from the East Side of New York, anyway! I can find a good ringer for him, and tell him what to say.”

“What have you got to do with it, Knippensky?”

“Everything! I wrote him! You furnish a clumsy Yankee idea, and I make it live!”

“Yes, and you got paid for it.”

“Yes, and I get paid a lot more for it, Mr. Brown! Either I get a fifty-fifty cut on the royalties of Dementia, or I bring Zuprushin over to lecture — and remember I’m given in the book as his translator and representative.”

Bill Hupp was doing Swedish movements with his large square hands. He begged “Shall I choke him or just punch him, boss?”

“Wait.”

While Mr. Hupp and Mr. Knippensky glared at each other, Mr. Brown sat and smoked and thought.

“Knippensky,” he said, “I think I’ll let you bring Zuprushin over.”

“Oh, thank you!” caroled Mr. Knippensky, and, took leave.

“Look here,” said Bill Hupp: “I thought you said you had come to hate Zup as much as I do.”

“Sure do I, Bill. If we told the truth about him nobody would believe us, though. But I think maybe I see a way to slaughter him.”

IX

When he left the office Mr. Brown started on a walk, the object of which was to keep away from the Liberté. He told himself that he hated Hobohemia even more than, in Northernapolis, he had imagined he would. He walked briskly. He found that his steps tended to turn toward the Liberté, but that was merely because in that locality the streets were not so much torn into trenches and shell-pits by the subway. As he walked, violently anxious over Ysetta, loathing himself for having invented Zuprushin, he began to think of the Liberté as a warm and entertaining place. He felt lonely in these quiet side streets. Mrs. Saffron would be at the Liberté, with her curious exciting smile; and maybe that good soul Jerry McCabe, of Direct Action. He needn’t go near the nuts like Max Pincus and Abigail Mara. It would have taken Mr. Brown seventeen minutes to walk from his office to the Liberté, if he had been going to the Liberté. But as his chief object was to keep from going there, it took him all of twenty-seven minutes to get there.

He bolted in, and threw off his melancholy as Mrs. Saffron hailed him, “Come join us, Denny.” He sat down with Mrs. Saffron, Max Pincus, Abigail Manx, Jandorff Fish, and a man he had never seen before.

The stranger was introduced. He was no other than that monumental British novelist, the personal friend of Zuprushin, Mr. James Jouse.

Mr. Jouse was almost prominently dressed. He wore a light tan overcoat with a wine-colored collar, a check suit, a crimson waistcoat with canary-yellow buttons, a terracotta tie with a brass pin placed diagonally, two thumb rings of opal matrices, yellow shoes with rubber soles, and spats. A walking stick four feet long and a pearl-gray derby hung on his chair. From this debacle rose his round, smooth-shaven, red, foolish face, a bang of rope-colored hair, and a long Chinese tobacco pipe with a brass bowl, which he kept refilling with pinches of powdered tobacco. This refilling was of advantage in that it interrupted his talk, and the most important fact about his talk was that it ought to have been interrupted. It boomed an insulting bass, while Mr. Jouse informed his hearers — which meant everybody within a block of the Liberté — that England was an ignorant nation; that he had left England during the war because he could not stand its insular attitude toward his friends the Germans; that America was an ignorant nation, also insular; that we were ignorant of our only geniuses, Whitman and Max Pincus; that sex had an inevitable tendency to be sex; and that he, Mr. James Jouse, was the only modern who could appreciate Zuprushin.

Mr. Brown suddenly realized that he wasn’t being paid by the Inland Lumber Company to stand Mr. Jouse. He interrupted:

“Strikes me that this Zuprushin is simply a fad.”

Mr. Jouse came to a thunderous halt. He looked Mr. Brown all over. The Jouse fans began to snicker. Mr. Brown felt uncomfortable.

“Ah?” said Mr. Jouse. “It is very amusing to get the Typical American Business Man’s opinion of a great spirit like Zuprushin. I take it that you are a business man.”

“I certainly am!” growled Mr. Brown.

“Ah, my friend! You see? Only the Germans have been able to appreciate James Jouse’s penetrating vision. Now, my friend, have you found that your brain — which is doubtless a most tremendous brain for business problems — has it been able to stand the strain of reading clear through one whole chapter in Zuprushin?”

Max Pincus was laughing so merrily — Mr. Brown saw that if he did his duty, and beat both Mr. Pincus and Mr. Jouse, the Liberté would be in an unfortunate state. He ran away, pursued by the thunder of Mr. Jouse’s voice and the lightning of Mr. Jouse’s waistcoat. He found a perfectly respectable restaurant, into which he was sure no Hobohemian had ever gone. Pathetically solitary, he ate a Swiss cheese sandwich, while on the back of a couple of envelopes he wrote the following hate song:

I, Dennis J. Brown — of Northernapolis, by golly! — do hereby hate and do cuss out, for keeps, all authors of the following classes:

High brainy authors who do scorn and contemn commercialized writing guys.

Husky writing guys who play golf and wear brokers’ ties and scorn high authors and otherwise try to pretend that they are not authors also.

Radical authors with a mission.

Lady optimists.

Writers of moral stories about cow-punchers.

Writers of immoral sex stories.

Authors with social position, especially those related to the best families of the South.

Authors who write about the broad prairies of the Middle West.

Authors who write about the broad ocean at or adjacent to California.

Authors who write about authors.

He scratched his head for a moment, then firmly added to his list:

All other kinds of authors.

X

Here were no more masterpieces emanating from the office of the Brown Productions Company. The stenographer and Oliver Jasselby had been discharged. All day long Mr. Brown and Mr. Hupp sat around and hated Zuprushin and waited.

In about a week they were pleased to see large posters announcing that Zuprushin had secretly arrived from Russia and would give a revolutionary lecture on The Passing of the Male, at Yearner Hall. By speaking in false and sympathetic bird notes to Mischa Knippensky, Mr. Brown and Mr. Hupp learned that Mischa was going to use a Grand Street butcher as Zuprushin. The butcher had a criminal record, but he was a clever parrot and was busily learning a speech which Mischa had written for him.

Mr. Brown and Mr. Hupp had one of the standard press pictures of Zuprushin enlarged to a noble thing, nine feet by four. They informed the superintendent of Yearner Hall that, by orders of Zuprushin’s manager, Mr. Mischa Knippensky, this portrait was to be hung on the proscenic arch on the night of the lecture.

They sought the original of the Zuprushin picture, Moe Witzig, the dealer in old, very old and not very sanitary garments. They took along a trusty court interpreter, but even with his aid they had difficulty in making Mr. Witzig understand that he was to be paid large sums for the pleasant and easy work of heckling a Russian genius. Mr. Witzig was understood to observe that he would see himself in Gehenna before he would have anything more to do with two Goys who hitherto, in an hour when he had trusted them and believed them, had taken him and bathed him in a distressingly uncanonical manner, and practically ruined the appearance of his derby and the luxuriance of his beard. He was a poor man, but he was learned in the Talmud, and he would be verflucht before he would again trust himself to them. They had to out the petition entirely on moral grounds, and speak reasonably to his wife, who helped them to persuade Mr. Witzig, and was present on the afternoon before the Zuprushin lecture, when the wailing Mr. Witzig was again disinfected and arrayed in the Russian blouse with embroidered collar which he had worn when the Zuprushin picture had been taken.

The Zuprushin lecture was advertised like a prizefight. It was pulled off in Yearner Hall, and every yearner after culture from Weehawken to Flatbush was in evidence. Before eight o’clock a queue half a block long was in front of the ticket window for the gallery. It was not the typical gallery queue, but a line of entirely proper schoolteachers, social workers and club women, who felt that Culture demanded that they go and swallow a large bitter dose of Zuprushin. The smallest and most anæmic women in the bunch had stern words to say about the truth of katanthropos.

Mr. Brown had taken a box for Ysetta, Mrs. Saffron and himself. From the box they gazed on the somewhat undistinguished-looking heads of the most distinguished people in New York. Mrs. Vanzile Deuzen had brought a dinner party, which occupied a whole row in the orchestra. In two boxes were the owners of four-ninths of the real estate in New York. The most celebrated tenor in the world sat in a stall near that of the president of one of the state federations of women’s clubs.

The peculiar thing about this audience was that it did not wait decorously for the curtain, as did most of the gentle assemblages at Yearner Hall. Everybody talked loudly. They were all hot on the trail of the Newest Culture, and baying their quarry. Through a frog pond of weaving noises Mr. Brown could hear the basso-profundo of Mr. James Jouse informing the world that he had a rotten seat, in this rotten hall, to hear the rotten lecture of that discredited charlatan, Zuprushin, a person whom Mr. Jouse would certainly refuse to meet personally, even if he were invited to meet him.