January/February 2017 Limerick Laughs Winner and Runners-Up

As the mist on the battlefield clears,

And the enemy regiment nears,

This lass in her nook

Foreshadows the look

Of Where’s Waldo? by 60-odd years!

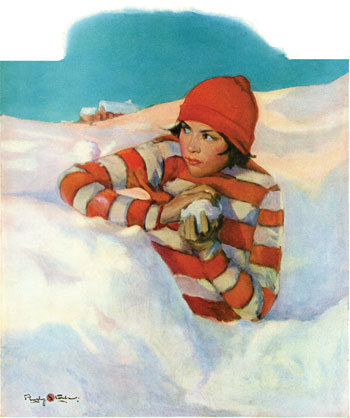

Congratulations to Jeff Foster of San Francisco, California! For his limerick, Jeff wins $25 and our gratitude for his witty and entertaining poem describing Penrhyn Stanlaws’ February 18, 1928, cover Snowball Fight (above). If you’d like to enter the Limerick Laughs Contest for our next issue of The Saturday Evening Post, submit your limerick through our online entry form.

We received a lot of great limericks. Here are some of the other ones that made us smile, in no particular order:

This red-hatted miss will aim true.

A snowball to her — nothing new.

Her eyes show her mettle;

There’s a score here to settle.

Aren’t you glad she’s not targeting you?—Diane Swan, Barre, Vermont

They laughed and they let her “pretend;”

The boys thought she could not contend.

A delicate flower?

They’d soon know her power;

They’d never again condescend.—Rebekah Hoeft, Redford, Michigan

When she throws as if pitching a batter,

Her snowball will make quite a splatter.

She’ll “powder” his nose

And make sure that he knows

That with snowballs, size really does matter.—Chris Bauer, Los Molinos, California

“There’s Sue (with her dumb, stupid bow)!

And that two-timing nincompoop Joe.

If I throw this just right

Using all of my might

I can clobber them both with one throw!”—Guy Pietrobono, Washingtonville, New York

Although she joined in just for kicks,

She soon realized it’s the pits

When the fight is to throw

Balls made out of snow

Constructed by hands without mitts.—Paul Desjardins, West Kelowna, British Columbia

My snow fort is ready to go,

Filled with balls roundly packed out of snow.

All I need is a chump

I can hit with a thump.

It’s all in the prep, as you know.—Louise DeDera

That girl in the red and white stripes,

I know her — she’s one of those types

Who tend to believe in

This way to get even

To settle her grumbles and gripes.—Neal Levin, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

A brazen young lady named Shammer

Threw snowballs that hit like a hammer.

But that came to a stop

When she hit a big cop,

And Miss Shammer wound up in the slammer.—Philip Simmons, Greenville, South Carolina

My advice — in a snowball fight, mind you —

Is to make sure that no one’s behind you.

If you just want to stay

Out of trouble, I’d say

Dress like Waldo, and no one will find you!—Jennifer Klein, Rehovot, Israel

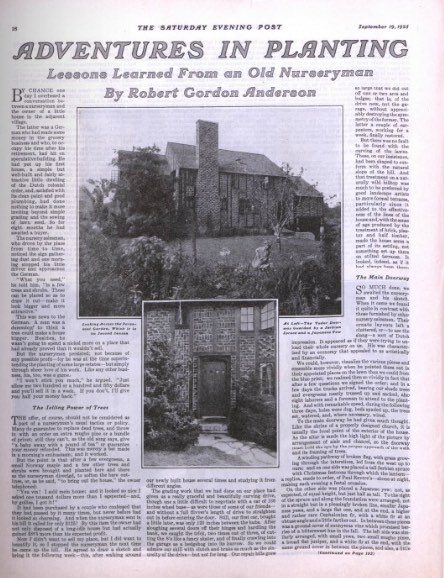

Was the American Chestnut Completely Wiped Out?

An Arbor Day observance would seem incomplete without a celebration of the majestic American chestnut. The tree is ingrained in our heritage, from the sweet, nutritious nuts “roasting on an open fire” to the sturdy, rot-resistant lumber that built our railroads and fences. From Maine to Mississippi, the American Chestnut once comprised up to 25 percent of the Appalachian forests. Early settlers admired these hardwoods that stood nearly 100 feet tall — that is, until we wiped them out.

The chestnut blight was first noticed by a forester in the Bronx Zoo in 1904. By the 1950s, the fungal disease had spread to Georgia, girdling every American chestnut in its path — an estimated four billion trees. The fungus was thought to have been introduced by way of chestnuts imported from Japan in the 1870s. These Asian varieties were resistant to the disease that devastated the eastern forests of the United States.

In a 1925 Post article, “Adventures in Planting,” Robert Gordon Anderson grimly predicted the chestnut blight: “Starting in New England some years back, it swept over the Hudson like an invisible prairie fire and so on to the West, making our American chestnut almost as extinct as the dodo; it will probably vanish quite as completely within the next 75 years.” As it turns out, Anderson’s prescient account underestimated the virulent fungus by about 50 years.

One question remains: Are there any American chestnuts left?

Many of the infected trees sent up shoots from surviving root systems after their demise. Unfortunately, these suckers succumbed to the same fungus after about 10 years — or 20 feet of growth. There are, however, many accounts of thriving American chestnuts in Michigan, Wisconsin, and the Pacific Northwest. These humble stands of trees could not possibly compare to the swaths of forests that once towered over a significant part of the country, but it’s a start.

The American Chestnut Foundation is a national nonprofit that collaborates with State University of New York to attempt a reintroduction of the tree to its original habitat. To accomplish this, the ACF is involved in continual research of the best way to utilize fungus-resistant properties of the Chinese chestnut in a hybridization with our beloved American chestnut. The research is slow-going because trees are slow-growing, but SUNY thinks they may have found the answer in transgenic trees. These are chestnuts that have been genetically altered by inserting one wheat gene into the genome of the American chestnut. That gene can help the tree fight oxalic acid — the toxin produced in chestnut blight.

Ruth Goodridge of ACF says they hope to crossbreed their hybrids with SUNY’s transgenic trees once approval is obtained from the USDA, EPA, and FDA. Since the organizations will be completing applications later this year, that approval could come by 2021.

“We hope to plant them everywhere. This is about the restoration of an ecosystem,” Goodridge said. She noted their interest in promoting biodiversity with American chestnuts, hoping to develop not only a blight-resistant tree, but also one that does not succumb to root rot, a malady more common in the South.

The chestnut blight was a devastating effect of globalization, but isn’t an isolated incident. Goodridge points to Dutch elm disease and the hemlock woolly adelgid as other examples of foreign pests and diseases that affect our forests in a big way. “We’re not just trying to save some old tree. This research could help prevent occurrences like this in the future.”

The prospect of American chestnuts stretching for miles again is an exciting one, but the only people likely to enjoy that view are the generations to come. If you want to view old-growth American chestnuts, there are some surviving specimens.

Perhaps the best way to commemorate the tragic tale of the American chestnut, however, is to appreciate the diverse species of trees that still cover this country: maples, oaks, tulips, and pines. You can start by planting one today.

News of the Week: Influential People, Landline Lovers, and the Most Expensive Dirty Jeans in the World

The Time 100

The annual Time 100 list celebrates “the 100 most influential people in the world.” But I think these lists are just an excuse for a publication to hold a big party where the people on the list have to come wearing fancy dresses and suits.

So who made this year’s list? Who is considered influential in 2017? Well, the obvious people are in the “Leaders” category, including President Trump, Pope Francis, and General James Mattis. But you’ll also find “Celebrities” like Emma Stone, “Icons” like writer Margaret Atwood, and “Titans” like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. Each person on the list has a little essay written by another famous person that accompanies their photo, such as Buzz Aldrin’s essay on Bezos and Oprah Winfrey’s essay on writer Colson Whitehead.

I don’t know if I learned anything from the list, except for the fact that ex-San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick is considered an “Icon.”

The Saturday Evening Post could probably come up with a list like this every year, but the people on it would all be dead presidents, artists, and writers, and the red carpet arrivals would be really boring.

Call Me

I’ve ranted several times in this column about the tyranny of smartphones and my love for landlines (you can also read Ron Carlson’s excellent essay about his love for them in the March/April issue). Robin Bernstein loves landlines too, and says in this Boston Globe essay that she still has one and she’s not apologizing for it.

Her reasons are not only emotional and nostalgic (and those are reasons enough to hold on to something in your life), but also logical. Landlines are more dependable and reliable than smartphones. They sound better, and they’re better for actual conversations. They’re the “sensible shoes” of the phone world, and there are many reasons to hope they never go away.

I still remember the big, black rotary phone that we had in the kitchen when I was a kid. Younger people today wouldn’t have liked the fact that it was heavy, you rented it from the phone company, and it wasn’t portable because it was attached to the wall by a wire, but I still think that’s the best phone I’ve ever used, and I miss it.

RIP Jonathan Demme, Erin Moran, Dick Contino, Cuba Gooding Sr., Kate O’Beirne, Chris Bearde, Kathleen Crowley, Robert Pirsig, Albert Freedman

Jonathan Demme was an acclaimed director, writer, and producer who could direct almost anything, from an episode of Columbo in the ’70s; to movies like Silence of the Lambs (one of the very few movies to win Oscars in all the top categories), Melvin and Howard, and Philadelphia; to concert films like Stop Making Sense and Storefront Hitchcock. He died earlier this week at the age of 73.

Erin Moran played Joanie, Richie’s sister, on Happy Days and the short-lived spinoff Joanie Loves Chachi. She also appeared in shows like Daktari, Family Affair, Gunsmoke, My Three Sons, The Love Boat, and Murder, She Wrote. She died last week at the age of 56.

Dick Contino was not only a famed accordionist, he was in one of the classic movies Mystery Science Theater 3000 took on, Daddy-O (“Must be Harry-O’s father.”). He was also in The Beat Generation, Girl’s Town, and I Was a Teenage Beatnik and was the subject of a James Ellroy novella, Dick Contino’s Blues. He passed away last week at the age of 87.

Cuba Gooding Sr. was the father of the Academy Award-winning son of the same name. You might remember him singing this great song with his band The Main Ingredient:

Gooding died last week at the age of 72.

Kate O’Beirne was a writer and editor for The National Review for many years. She also worked in the Department of Health and Human Services under President Reagan and was a regular panelist on the CNN politics show The Capital Gang. She died Sunday at the age of 67.

Chris Bearde created The Gong Show and was a writer on Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In and other shows. He also produced That’s My Mama and variety shows like The Andy Williams Show, The Bobby Vinton Show, and The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour. And he co-wrote Elvis Presley’s famous 1968 comeback special on NBC. Bearde died Sunday at the age of 80.

Kathleen Crowley was an actress who appeared in sci-fi/horror films like Target Earth and Curse of the Undead, as well as the classic drama Downhill Racer. She also appeared in dozens of TV shows, such as Perry Mason, The Donna Reed Show, 77 Sunset Strip, Bourbon Street Beat, Hawaiian Eye, Route 66, Batman, and seemingly every TV western ever produced. She died Sunday at the age of 87.

Robert Pirsig wrote the experimental novel Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. It was rejected by 121 publishers but is now considered a classic. He died Monday at the age of 88.

Albert Freedman was the producer who got Charles Van Doren on the game show Twenty-One in 1956 and later coached Van Doren on the questions he would be asked on the show. This led to the infamous quiz show scandals and Freedman’s eventual blacklisting from television. (Hank Azaria played Freedman in the movie Quiz Show.) He later went on to work for Penthouse. He died on April 11 at the age of 95.

For Sale: Marilyn Monroe’s House

I could have sworn that the house where Marilyn Monroe died had been torn down years ago, but apparently it wasn’t. In fact, if you have $6.9 million, you can buy her Brentwood, California, hacienda. It has four bedrooms, three bathrooms, a swimming pool, new additions to the kitchen and other areas, and a rather interesting history.

It was also once owned by Hill Street Blues actress Veronica Hamel, but I doubt that’s a real selling point.

For Sale: Muddy Jeans, Never Used. $425.00

If you can afford Marilyn’s house, you can probably afford these jeans, though I wouldn’t suggest buying them. They’re called PRPS Barracuda Straight Leg Jeans, and they’re absolutely filthy. I’m not insulting them, they’re actually filthy. They look like someone dropped a hot fudge sundae on them and then never washed them. They come that way, for all of you jeans-loving consumers who are too lazy to do any actual work that would get your pants all dirty and muddy.

I used to think that buying jeans that came with a hole already in the knee was ridiculous, but these jeans easily top those. Soon you will be able to buy jeans that are so ripped and dirty and frayed and filled with holes that the moment you take them out of the box, you immediately throw them away and buy another pair.

This Week in History

William Shakespeare Born (April 23, 1564)

I bet you’ve always wondered what happened when William Shakespeare tried bubble gum for the first time. Al Graham has the answer.

Library of Congress Established (April 24, 1800)

The Library of Congress is the nation’s oldest federal cultural institution. Its website is one you probably don’t think about visiting, but you really should. It has a ton of fascinating information.

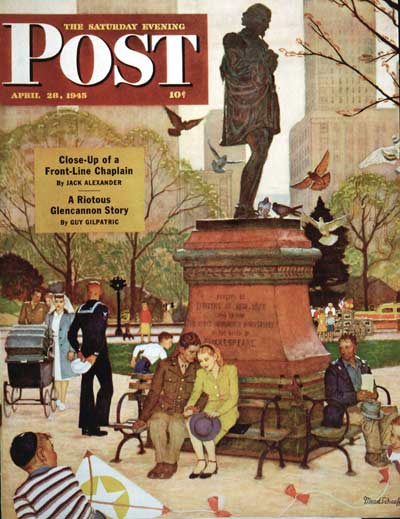

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: “Romance Under Shakespeare’s Statue” (April 28, 1945)

April 28, 1945

Mead Schaeffer

Speaking of the Bard, this cover is by artist Mead Schaeffer. He had to paint it twice because the Vermont set was so cold his canvas froze. He put his daughters in the picture: one daughter is the woman on the bench with the man, and the other is the nurse near the baby carriage.

National Blueberry Pie Day

What’s your favorite pie? Mine is a really boring choice: apple. Actually, I don’t know why I call apple a “boring” choice. It’s predictable and obvious, but a lot of favorite things in life are predictable and obvious. My favorite movie is It’s A Wonderful Life, and I love pizza.

But this isn’t about Jimmy Stewart or pepperoni, it’s about blueberry pie. Today is National Blueberry Pie Day. Here’s a classic recipe from Allrecipes, and here’s a Cream Cheese Blueberry Pie from Taste of Home.

You ever notice that when a pie-eating contest is depicted in a movie or a TV show, the contestants are always eating blueberry pie? That’s probably because it’s easier to show blueberries on someone’s face than apple or pecan. And it’s funnier, too.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Star Wars Day (May 4)

Why is it Star Wars Day? “May the fourth be with you!” Here’s the trailer for the next film in the series, The Last Jedi, which opens this December:

Cinco de Mayo (May 5)

This day celebrates the Mexican victory over French troops at the Battle of Puebla in 1862. But please don’t confuse it with Mexican Independence Day, which is a completely different thing.

Revelation

I don’t know if you’ve figured it out for yourself, yet, but you can’t trust grown-ups. Even the ones you think you can trust. Like your parents. It’s not like they actually lie to you, mostly, but they try to make you think about stuff the way they want you to think about it. It’s really just to make things easier for them. At the same time, you have to kind of admire the way they’re always playing the angle on you. Getting you to do things you really don’t want to do, and you never even know it. Smart.

Like last month, when I started digging around for my old catcher’s mitt. My old man gave it to me a couple years ago. It was really just a kid’s mitt — it was pretty flat, with no pocket at all. But Mr. Porter, the fourth grade gym teacher at Cherry School, said he was going to start up a Little League baseball team.

I’m actually not a bad player for my size — it’s just that my size is so small. Every single kid in the fourth grade is taller than me. In group pictures I always have to sit in the front row with the girls. That irritates the heck out of me, because Leon and his buddies always call me girlie names and give me a hard time.

Anyway, since none of the other kids ever wants to catch in pickup games, I thought maybe I could make the team as a catcher. Besides, catchers get to wear a mask and all those pads and stuff, which is kind of cool. They might make me look bigger. Plus, Yogi Berra was my favorite player and he was a catcher for the Yankees. I just read his biography. Believe it or not, his first name is really Lawrence.

About my mitt. I guess I must have left it lying around a lot. Anyway, Mom told me about a hundred times, “David Abbott, if I have to pick up that darn blah blah blah blah throw it out!” And then one day she did! It was just a kid’s mitt, and I didn’t miss it much. But then I needed it again. I started griping about how unfair it was to just toss something like that when it’s your kid’s favorite thing, a gift from his father. If I didn’t have it, I’d never get to play Little League. I’d never have any friends. I’d be a failure in life. Angling for a new one, of course.

One night, we were sitting around watching The Ed Sullivan Show. I was moaning about my mitt when my old man said, “You know, sometimes if you pray hard enough, God will give you what you want. Why don’t you try praying for your old mitt?” That sure sat me up straight. Yeah, he was always going on about God and trying to make me go to church. Even though he always slept in Sunday mornings. But whenever I asked him to name anything God had done since a bazillion years ago to prove he was still around, he’d get ticked off. I’d get the true believer speech.

“A true believer blah blah blah didn’t need deeds blah blah just has faith.”

Ha. To me, true believer was spelled s-u-c-k-e-r. I went to church, but only because he’d ground me if I didn’t. But there he sat, smirking at me over the top of his beer can, actually daring me to try it for myself!

Naturally, I had to take him up on it. I didn’t know how he expected to pull this off, but I didn’t see as I had anything to lose. When the mitt didn’t show, maybe he’d back off on the God thing for a while. For more than a week, I prayed every night for that mitt. I tried hard to stay serious. But if there really was a God, I knew he was getting a chuckle out of it.

Then one Saturday, as I was pawing around at the bottom of my little brother’s toy box, hoping to come up with a piece of red crayon — there it was! My old catcher’s mitt! Holy Toledo! I got goose bumps up and down my arms. Did this mean there really was a God? And worse — was I going to wind up a hunk of stew meat in the devil’s pot for all the grief I’d given my old man about it?

I knew the mitt hadn’t just been buried there all this time. I’d been through that toy box top to bottom a hundred times since my mom pitched it out. It was put there by someone. But by who? That was now the $64,000 question.

I went flying downstairs, mitt in hand. “Look what I found!” I shouted.

My old man pulled himself away from the television long enough to rub it in. “Well!” he said. “Your prayers must have been answered. I told you that happens sometimes. I hope you’ll be properly thankful.” He jabbed his cigar at me in emphasis.

“You put this there, didn’t you?” I demanded.

“No, I did not,” he said. “You told me yourself that your mother threw it out a long time ago.”

True. That was a stopper.

“Are you telling me that God put it there?”

“I’m not telling you anything. I didn’t put it there. You’re the one who did the praying — you tell me.” He sat there with his feet up, sucking his cigar and looking smug.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get anything else out of him. I gave Mom a shot. She stuffed her hands into the little pockets of her faded blue apron and said, “You’ll just have to listen to your father on this one. I don’t know anything about what God does or doesn’t do.”

I didn’t know what to believe. If my mom said she threw it out, she threw it out. But here it was. And my old man said he didn’t do it, and he probably wouldn’t tell me an outright lie. At least not one he could get caught in. And if there really was a God, my immortal soul was on the chopping block for all those years of cussing and joking about him. To me, the whole idea of a God just didn’t add up. But a heck of a lot of smart people went to church on Sunday.

Maybe they were right, and I was standing out in left field.

I spent the rest of the day worrying about going to hell and trying to put a pocket in that pancake of a mitt. I soaked it with water and put an apple where the pocket should have been. I folded the mitt around the apple, then tied it up tight with twine and put it in the sun to dry.

I pulled the Bible off the bookcase and tried to read a couple of pages. It was boring, and it had lots of weird words. I couldn’t make any sense out of it.

My agony ended the next day. Mom was in the basement doing laundry. My pipsqueak brother and I were eating lunch at the table in our tiny kitchen. He was busy trying to rub the freckles off the back of his hand. Nobody else in the family had freckles. My old man was always joking with my mom about the mailman having freckles, too, but I couldn’t figure why she thought it was so funny.

“Hey, Davy?” he said.

“What, Squid?”

“I know about your catcher’s mitt.”

“Yeah, it just turned up again — isn’t that really weird?”

“No, I mean I saw Mama find it.”

I froze, with half a baloney sandwich in my mouth. I had a feeling I wasn’t going to like this. I swallowed the whole thing without chewing.

“Okay, what?”

“I was up in the attic, looking in the old boxes, and I heard Mama coming. I hid in the blanket pile where she couldn’t see me. She went to the big black trunk and took out the mitt.”

I was stunned. I didn’t believe it at first, but the squid wasn’t bright enough to make that up on his own. It had to be true.

“Davy?” he said.

“Huh?”

“You okay?”

“Of course I’m okay. Whaddaya think? Anyway, you’re not supposed to be in the attic. How the heck did you get up there?”

“I sneaked up. I did the thing with the broomstick.”

Rats. I’d showed him how to lift a hook off the little screw eye with a broom handle. Maybe that wasn’t so smart after all.

“Don’t tell — I’ll get in trouble.”

“No kidding. You’re a regular Sherlock Holmes.”

“You’re not gonna tell, are you?”

“No, but you better not go up there any more — you were just lucky this time. Don’t forget about the belt!”

He turned pale. “I won’t, I won’t!”

I walked back into the living room and picked up the Bible I left out. I put it back on the bookshelf.

So, I’d been played for a sucker by my own loving parents. That seemed a little low, even for grown-ups. On the other hand, I had a catcher’s mitt I didn’t have yesterday. And I still might play Little League. And any interest I had in church and any fear of roasting my butt on a spit in hell were gone like a fart in a windstorm.

I decided to call it even.

The President with the Most Successful “First 100 Days”

The concept of the “first hundred days” reduces a large, complex undertaking — the achievements of a president — to a deceptively simple scale.

Franklin D. Roosevelt first used the term on July 24, 1933, to describe the early accomplishments of his administration. In a radio address to the nation, he said it was time to look back at “the crowding events of the hundred days which had been devoted to the starting of the wheels of the New Deal.”

FDR’s accomplishments were impressive. He called the 73rd Congress into session early, and before his first week was over, presented his Emergency Banking Act.

At the time, banks across America were failing at a fearful rate. Fourteen hundred banks had shut their doors in 1932. Before 1933 ended, another 4,000 banks would close. The Emergency Banking Act closed every bank in America for one week, enough time for the public panic to subside. When the banks reopened, Americans began re-depositing their savings.

The Act was only the beginning of Roosevelt’s initiatives over the first 100 days. Before Congress adjourned, the administration also

- took U.S. currency off the gold standard, effectively allowing the government to print and distribute money to the struggling banks

- imposed regulations on U.S. banks that separated commercial banking from investment banking, and prohibited banks from using their assets in stock market speculations

- established an insurance program for bank accounts (the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation)

- introduced new regulation of the stock market (creating the forerunner of the Securities and Exchange Commission)

- created an agency that paid farmers not to raise crops, in order to raise the prices they got for their produce

- launched the Civilian Conservation Corps, which eventually put 250,000 young men to work on conservation projects

- started a program (the Tennessee Valley Authority) to provide electricity to impoverished rural Americans and raise their standard of living

- created a controversial program that placed pricing controls on businesses in an effort to raise the cost of goods

- began the Public Works Administration to create jobs building schools, hospitals, airports, dams, and other public projects

- provided training and direct relief to the unemployed

If it seems impossible for a president to accomplish all this in 100 days, it is. Roosevelt couldn’t have done this on his own, and he knew it. He relied on three other factors.

The first was Congress. Most of the changes came through legislation, not executive orders. Roosevelt knew he could rely on the support of other Democrats who made up the majority in both houses. (The 73rd Congress had 311 Democrat, 117 Republican, and 5 Farmer-Labor representatives in the House; and 59 Democratic and 36 Republican senators, plus one from the Farm-Labor Party.)

Second, there was a national sense of urgency. One in five Americans was out of work. Employed Americans feared their job or savings might disappear overnight. Congressmen knew they had to act, even to try unconventional means. Southern Democrats sometimes objected to Roosevelt’s program, but progressive Republicans from western states stepped in to throw their support behind the president.

Third, Roosevelt had strong support from the American public, which had just elected him by 472 electoral votes to President Hoover’s 59. (Hoover lost the popular vote in 1932 by the same sizeable percentage he’d won it in 1928: 17%.) They had voted for, and would support, any new measures.

Other presidents haven’t had those advantages. When President Johnson entered the White House, he enjoyed a honeymoon phase with the press and the public. It enabled him to push the Civil Rights Bill, which had been hung up in Congress. He introduced a wide range of bills, hoping to beat Roosevelt’s record, but he failed.

President Reagan’s first 100 days got off to a promising start when 52 Americans being held hostage in Iran were released on the same day he took office. He also proposed $41 billion in budget cuts and major tax breaks during his first three months. President Obama took action on an ambitious number of foreign and domestic issues, including a $700 billion stimulus bill, but he still fell short of FDR’s record of change.

Roosevelt still holds the record for accomplishment in his first 100 days in terms of major legislation passed, but considering that it took a financial disaster and a desperate sense of national urgency to achieve so much, perhaps it’s just as well we never see his record beaten.

Featured image: Shutterstock

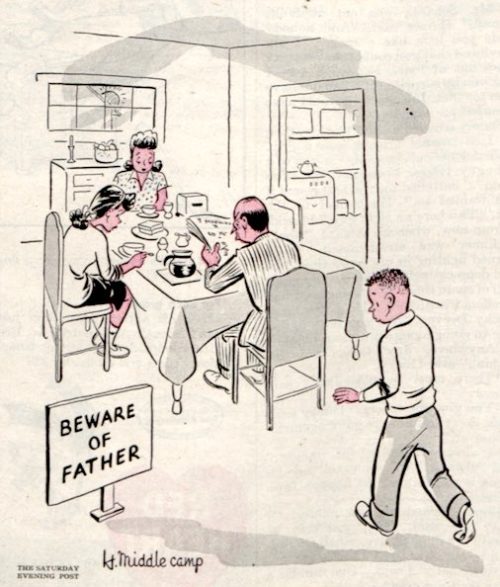

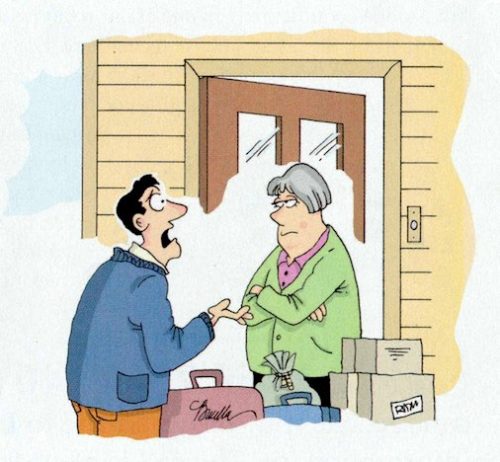

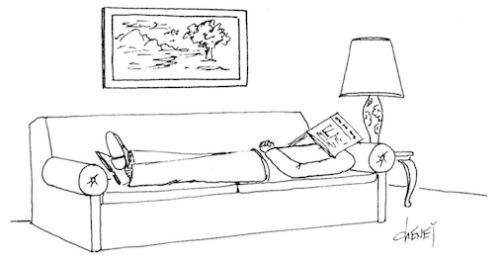

Cartoons: Home Sweet Home

Home: where you are loved the most and act the worst!

Fred Balk

December 28, 1940

December 11, 1943

H. Middlecamp

January 4, 1947

Stan Hunt

December 27, 1947

Shep

January 3, 1948

Stan Hunt

December 28, 1957

Nick Downes

July 1, 1991

Marty Bucella

September 1, 2010

Tom Cheney

June 1, 2015

Making the Case for ‘Big Brother’

A Look at the Post’s Occasional Lapses in Judgment

When Americans became concerned about FBI eavesdropping on private citizens, the editors of the Post dismissed such fears as paranoia.

There has been a lot of arguing recently about who is to blame for the large amount of electronic eavesdropping done by the FBI, but it seems worth asking why there should be any blame at all. It seems only reasonable that most of the information the police would like to get by eavesdropping is information that would lead to the prevention or solution of crimes. Is it not possible that our unthinking anxiety about “Big Brother” eavesdropping on us is a sign not of civic virtue but of paranoia?

—“Why Get Bugged about Bugging?” Editorial, January 14, 1967

This article is featured in the March/April 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Con Watch: How to Protect Yourself from Robocalls

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Technology has made life easier for us in many ways, but it also has made life easier for scammers who use computerized autodialers to blast millions of pre-recorded phone messages called robocalls. These calls are intended to cheat people out of their money in a variety of ways, including by luring them into providing personal information that is used for identity theft or to sign them up for worthless goods and services.

One of the most infamous robocall scams involves “Rachel from Card Services,” whose recorded message tells people they are eligible for a lower interest rate. You are then connected to a scammer who promises a low rate in exchange for your credit card number or other personal information.

“Rachel from Card Services” was a scam: Victims’ interest rates were never lowered, and the victims were charged for services they didn’t want. Scammers using the same “Rachel” recording have been shut down numerous times by the Federal Trade Commission and various law enforcement agencies, but, like playing whack-a-mole at a carnival, as soon as they stop one robocall scammer, another pops up. According to the FTC, Americans received approximately 2.4 billion robocalls each month during 2016.

Recently, the FTC and 10 states took action against a scammer who used illegal robocalls and telemarketing to sell Caribbean cruises. Victims were told they would receive a free cruise merely for participating in a survey; the callers would then talk their victims into paying for expensive, higher-level cruise packages. Between October 2011 and July 2012, the scammers made 15 million illegal robocalls each day.

Can’t You See Them Coming?

Through a technique called spoofing, some robocalls may appear on your Caller ID as coming from a legitimate source, such as the IRS (which does not use robocalls). This tactic tricks many people into believing that the call is legitimate. Fortunately, it’s easy to know when there’s a scammer on the other end of a robocall. Since 2009, it has been illegal for commercial robocalls to be made to you without your written permission. Politicians, pollsters, and charities are still permitted to make robocalls.

However, you can never be sure who is on the other end of the line, so you should never provide personal information, such as your credit card number, to anyone calling you. If a robocall gets you interested in donating to a particular charity, you should still terminate the call and look up the charity online to see where to make a donation.

How to Protect Yourself from Robocalls

One step you can take to help protect yourself from robocalls is to sign up for the federal Do-Not-Call List for both your landline and cellphone at www.donotcall.gov. Once you are on the Do-Not-Call List, legitimate telemarketers are not permitted to call you. So if you get a call from a telemarketer after you have enrolled, you know that the call is from someone who is violating the law and cannot be trusted.

If you ever do answer a robocall, never press 1 or any other number, even if it’s only to be taken off of a calling list. Pressing any number during a robocall only confirms to the scammer that your number is legitimate, which means they’ll keep calling.

You can also check with your phone company to ask what they are doing to help block robocalls. Phone companies and the Federal Communications Commission are both working to reduce the number of robocalls. AT&T recently announced that it is using analytic software to detect suspicious calling patterns, such as repeated short calls to phone numbers on the federal Do-Not-Call List. According to AT&T, it screens about 1.5 billion calls a day and blocks approximately 12 million robocalls each weekday. T-Mobile now offers a service called Scam Block that alerts its customers to likely robocalls. The customer can then choose to either ignore or answer the call.

Finally, you can use software to block suspicious calls. In 2013, the FTC had a contest to develop a way to effectively defeat robocalls. The winners were Aaron Foss and Serdar Danis, who developed software that filters out automated or suspicious telephone calls. Their software is available through Nomorobo; it’s free for landlines and $1.99 per month for cellphones.

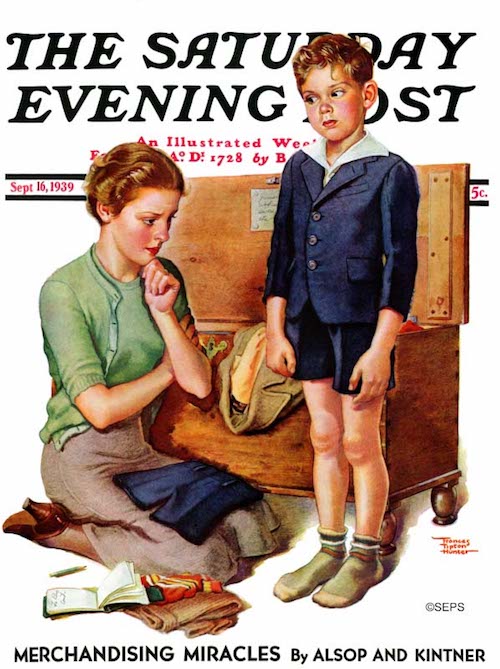

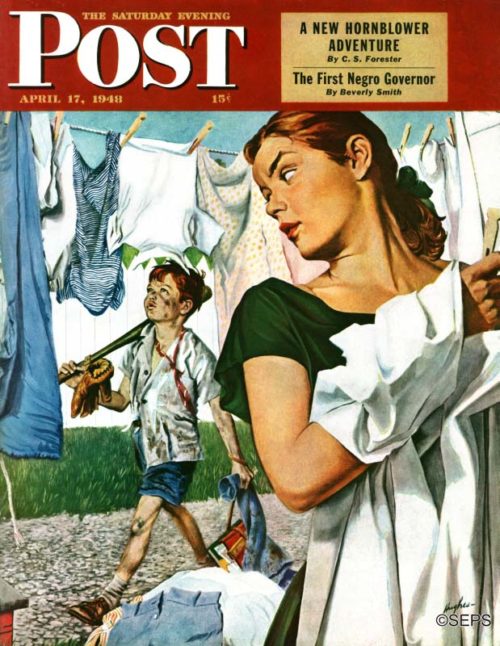

Cover Gallery: Mid-Century Mothers and Sons

People talk about the special bond between mothers and sons, but some of these ‘40s and ‘50s moms don’t look so sure.

Frances Tipton Hunter

September 16, 1939

Any mother can relate to the problem of the growth spurt, as painted by Frances Tipton Hunter, who created 18 covers for The Saturday Evening Post. Hunter was particularly interested in drawing children and animals. She also illustrated a series of paper dolls in the 1920s for the Ladies’ Home Journal, which proved to be extremely popular.

George Hughes

April 17, 1948

[From the editors of the April 17, 1948, issue of the Post] The old, old losing fight to keep a boy in clean clothes, when in five minutes he can get dirtier than a grease monkey, is noted here by an artist taking his first crack at a cover. He is George Hughes, one of the country’s best-known illustrators, whose work in that field is highly familiar to Post readers.

Stevan Dohanos

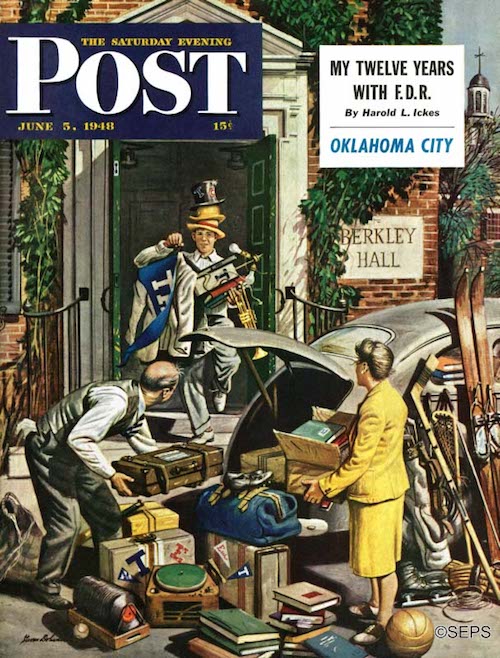

June 5, 1948

[From the editors of the June 5, 1948, issue of the Post] Stevan Dohanos’ two sons, Peter and Paul, were in an Eastern boys’ school and about this time last year, getting-out time, he took the family car up to help them move home. A passenger car, he learned, is no proper vehicle for such a job. It calls for a light truck or van. Brooding about this, and what it meant for the future, Dohanos mentioned his trip to a friend with a son or sons in college. They told him his real moving jobs are still ahead, when he tries to load the contents of one college room. The artist made his sketches on the Yale campus, but rearranged things to suit his purposes. The boy is George Ritter, of Westport, Connecticut, no Yale man. The artist didn’t use a Yale man, on the remarkable theory that none would like to cut class.

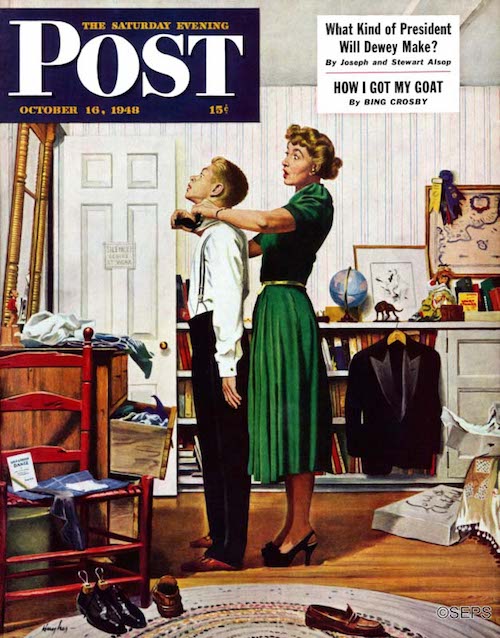

George Hughes

October 16, 1948

[From the editors of the October 16, 1948, issue of the Post] It’s that suspenseful occasion when a young man puts on his first tuxedo to go out to a formal party—or more commonly, first puts on his father’s tuxedo or one borrowed from an older brother. Looking around for models, it occurred to artist George Hughes that some of his neighbors would serve excellently. The boy getting ready to dazzle them at the dinner dance, if he doesn’t forget and wear moccasins, is Tommy Rockwell, son of artist Norman Rockwell. The woman essaying the puzzling job of tying somebody else’s tie is Tommy’s mother. That is Tommy’s room, in Arlington, Vermont, and Hughes was much impressed—he thought it remarkably tidy, as boys’ rooms go. Temporarily tidy, at least, and you can’t ask more than that.

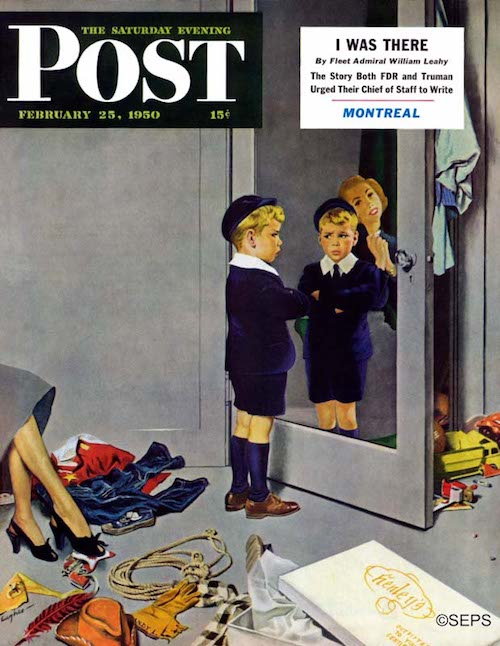

George Hughes

February 25, 1950

[From the editors of the February 25, 1950, issue of the Post] “Outfitters to Young Gentlemen,” proclaims the suit box, in a blundering effort to make the victim of its contents feel as swell as he looks. The young character does not wish to look like a young gentleman. What, he wonders in horror, will the gang down the street think when he bursts upon their gaze and is recognized as the guy they had always thought of as a normal, gun-toting cowboy? Will they clasp their hands as mother is doing, only with a less complimentary ecstasy? One ray of hope plays on the dark scene. In the next few weeks other misguided mothers will get this same new-suit fever, and on Easter Sunday many young cowpokes, in similar outrageous disguises, will be comforted by their companionship in misery.

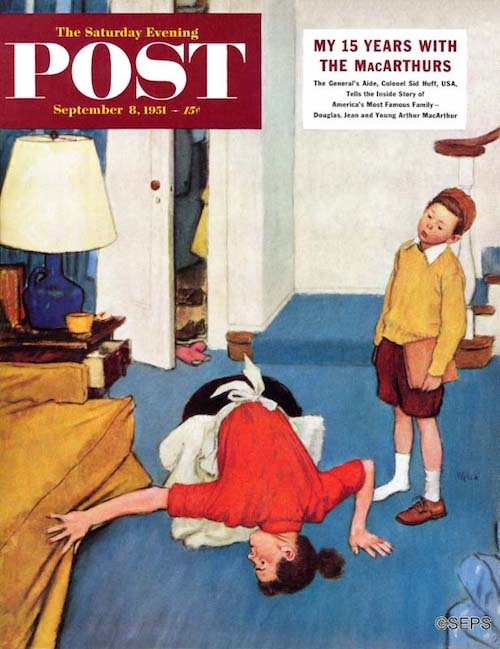

Jack Welch

September 8, 1951

[From the editors of the September 8, 1951, issue of the Post] This mother’s face is charming upside-down, but if you will also stand on your head, you will find that she wears a choleric expression. She is mad at her son, which is unreasonable, for she herself has lost his shoe. He took it off last June, and is it not a woman’s duty to take care of her men’s clothing? We know where the shoe is: it is either in the Apache hide-out under the forsythia bush, in the cowpoke’s corral in the vacant lot down the street, or Fido is preserving it in his kennel as an objet d’art. Junior will go to school in sneakers, and nobody will care except his mother, who doesn’t go to school. Next week she very likely will think all this is funny, and what the moral of Jack Welch’s theme is, we don’t know.

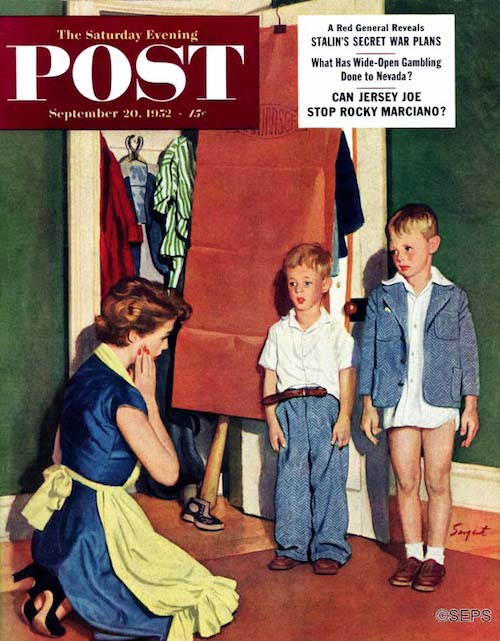

Richard Sargent

September 20, 1952

[From the editors of the September 20, 1952, issue of the Post] Inventors are so smart at dreaming up new types of cloth, why doesn’t some bright fellow concoct a rubber-base fabric, so that the suit of an expanding boy can occasionally be put on a stretcher and thus increase in pace with its master? When this idea goes into production, we get a 10 per cent cut or somebody gets sued. Meanwhile, Dick Sargent’s distraught homemaker can take a few gussets in that stationary suit and hang it on Son #2, but then the boy will promptly outgrow it. Oh, for the deflated old days when it wasn’t necessary to stop eating for a while to finance a new suit or stop buying suits to eat. Well, better times ahead, mother! Soon the lads will be big enough to hand down their clothes to their father.

Amos Sewell

November 8, 1952

[From the editors of the November 8, 1952, issue of the Post] Little Johnny Tomorrow has just walked past young Mr. Today, making the latter look aged and out of date. It reminds us of a sad occasion when an airliner captain asked a little passenger if this was his first time up. “Fourteenth,” said the lad. ‘Can’t ever get up higher ‘n five, ten thousand feet in these old planes, though. How’s the United States ever going to build a space platform if you fellas can’t make altitude?” The captain, epitome of modernism, turned green and crept away to rev up his creaky old engines; and the boy should have been spanked for insolence, except that actually he had his feet on the ground. When artist Sewell’s youngster gets tired of wearing that helmet, the hostess could put it on somebody who is snoring.

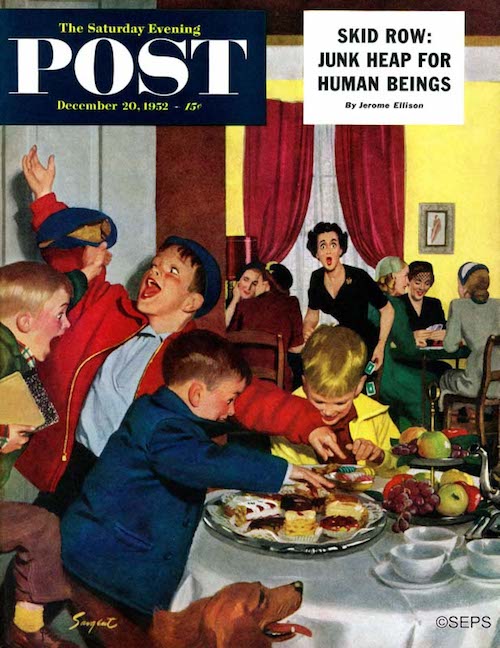

Richard Sargent

December 20, 1952

[From the editors of the December 20, 1952, issue of the Post] What is lovelier than the glow of care-free joy in the faces of happy children? Will the lady on the cover have the time to defend her food and change those expressions to the pinched melancholy of starvation? She will if she can make it across the room in time. It will be fairly cruel if she imprisons the lads in the kitchen with nice, healthy, disillusioning peanut-butter sandwiches, but not as cruel as the time Dick Sargent set up that enchanting pastry in his dining room to paint. He has sons. The mouths of the sons began to water. They watered for a week. Two weeks. Three. Then the sons were released at the pastry. They ate it so fast they apparently did not notice it was petrified, claims the fiendish father.

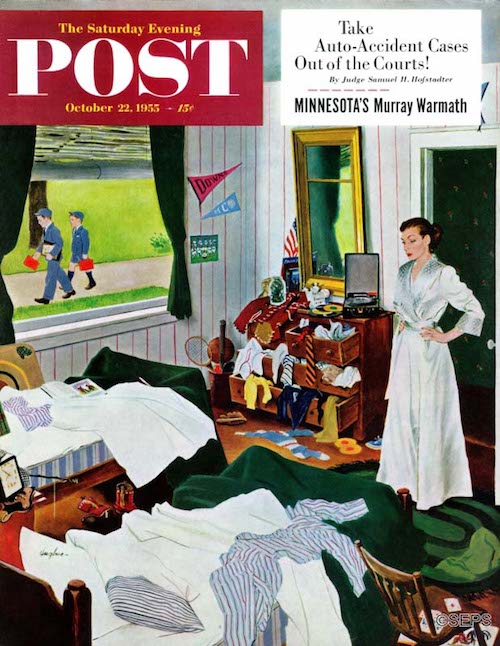

George Hughes

October 22, 1955

[From the editors of the October 22, 1955, issue of the Post] Mother is making rapid progress at teaching the boys to maintain a tidy room; if George Hughes had painted this the day school opened, the detail would have given him a lame arm. Now, here is portrayed an intelligent female who in her delicate way molds the character of men; so, when her boys are seniors in college, they will be 27 per cent tidier than now. Then they will get married and never leave so much as a pipe cleaner lying about—for six weeks. After that they will revert to human beings, and what they don’t chuck around will be what they haven’t got. A woman’s picking-up-stuff is never done. Why doesn’t this mother shock the boys into tidy conduct by simply leaving their shambles untouched? Because they like it this way. She’d better go buy herself a new hat.

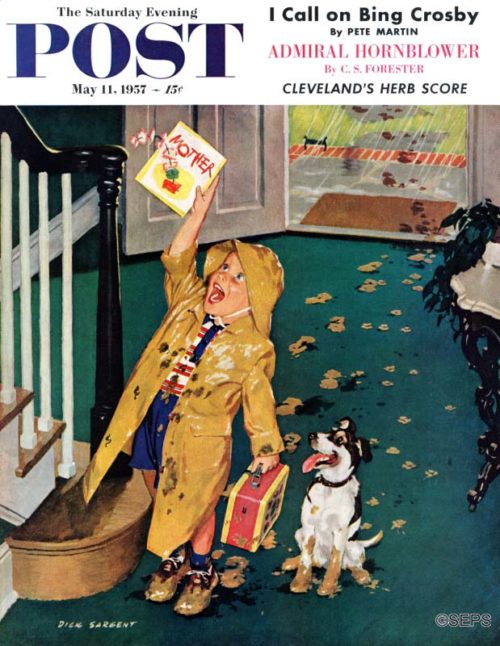

Richard Sargent

May 11, 1957

[From the editors of the May 11, 1957, issue of the Post] Johnny’s happy shout of “Mother, I’ve brought something for you!” is an understatement. Dick Sargent certainly can paint the most delicious-looking mud; did he use maple fudge for a model? Now then, when mother regards her ex-clean carpet and the adoration in the eyes of her seldom-so-soiled son, what type of emotion will possess her? Although a mother’s ups and downs often come simultaneously, and situations like this are all in the day’s work and love, the temperature of her reaction will depend partly on whether she’s a phlegmatic soul or pop-offy soul. Yet it’s a good bet that before she undertakes to make things come clean, she will administer to her son, fudge and all, a good, sound—kissing. Afterthought: if Fido decides to shake himself, all bets are off.

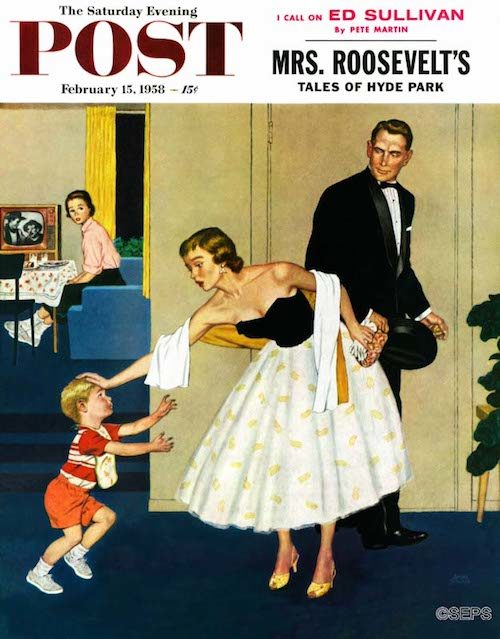

Amos Sewell

February 15, 1958

[From the editors of the February 15, 1958, issue of the Post] It’s typical of the male sex that Johnny is realizing how much his favorite lady means to him only when she is about to go away—and that’s enough psychology for this week. So John wants to cling to her, which will overlay a stunning new chocolate pattern on her dress, a chic addition to what seems to be a golden-fingerprint motif already put there by designer Amos Sewell. Without meaning to be unreasonable about this, is Miss Sitter going to come to the rescue or wait until the television program ends? Johnny’s situation is a bit pathetic as mamma delivers what football fans will recognize as a beautiful straight-arm; yet he does have loving parents, a swell home, luscious food, brisk entertainment and a pretty girl to dine with—what more can a young fellow ask?

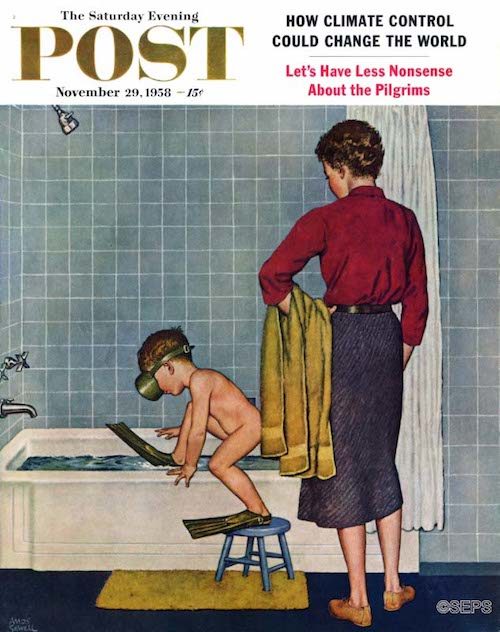

Amos Sewell

November 29, 1958

[From the editors of the November 29, 1958, issue of the Post] It looks as if artist Amos Sewell’s cover urchin is entering a bathtub of his own free will, and is therefore outwitting himself. Johnny’s decision to try out his diving gear has made him forget to remember that using water for the purpose of getting clean is bitterly repugnant to him. Mother could remind him of this, but why burden his little mind with confusing thoughts? So down Johnny will dive into the mysterious depths, seeking treasure on the floor of the sea, and down there he may well find a bar of soap. Then if mother and son excitedly agree that Johnny has found a rare specimen of submarine life worth maybe a trillion dollars or more, they will be sharing just a little white lie from which, as mother makes with the soap, great good will come.

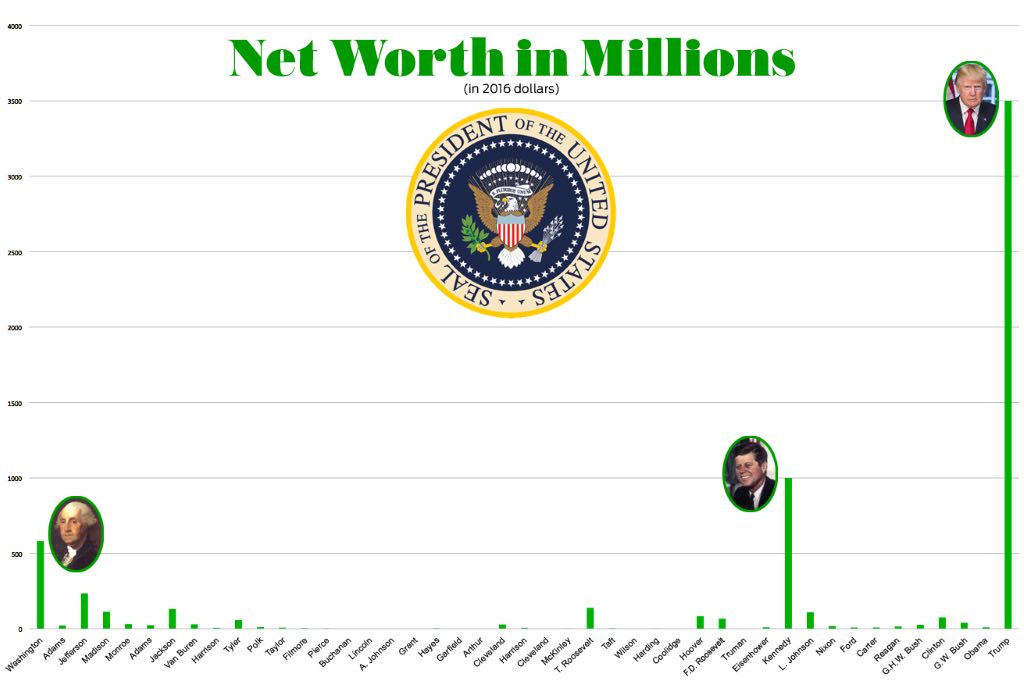

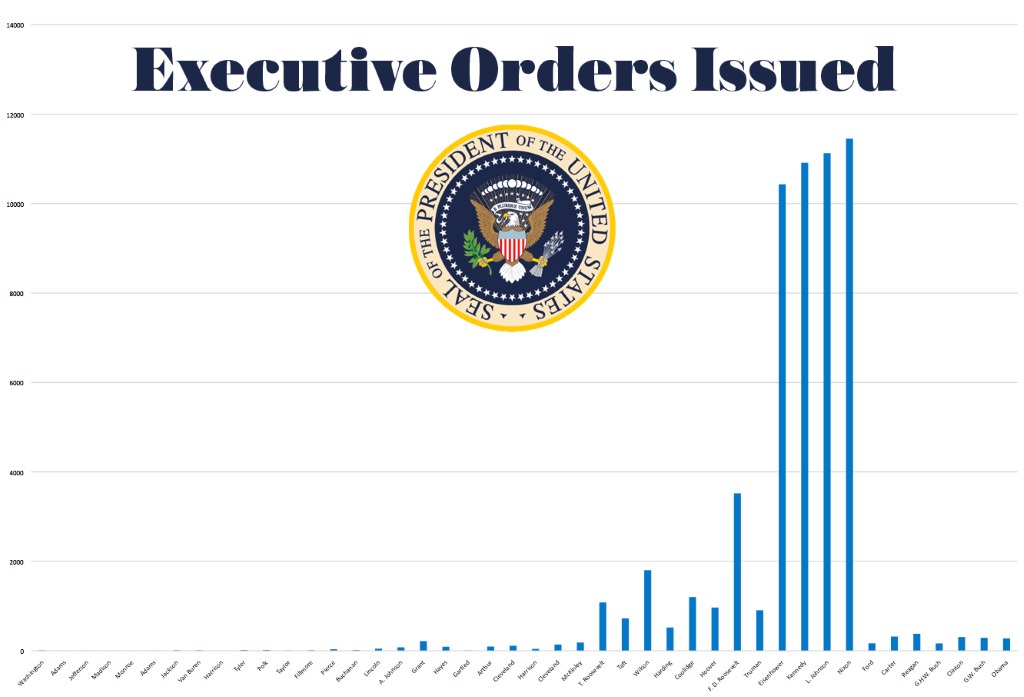

The Story of the Presidency in 7 Charts

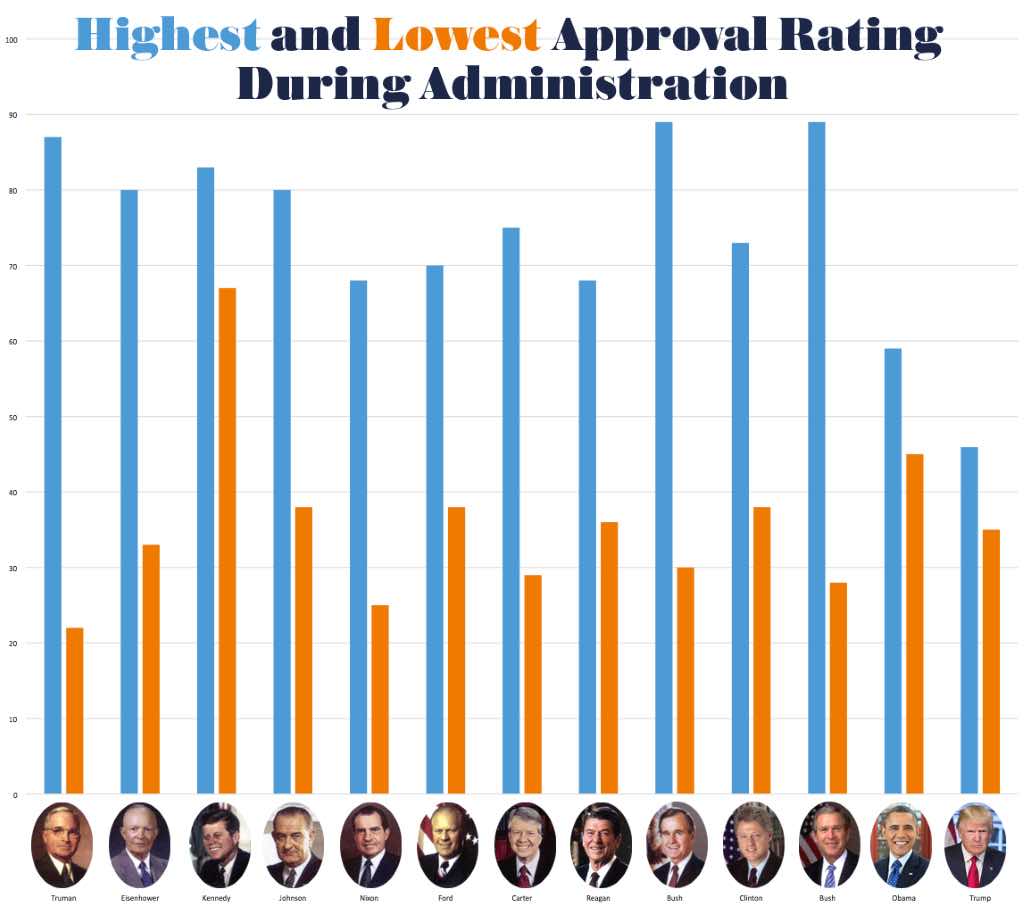

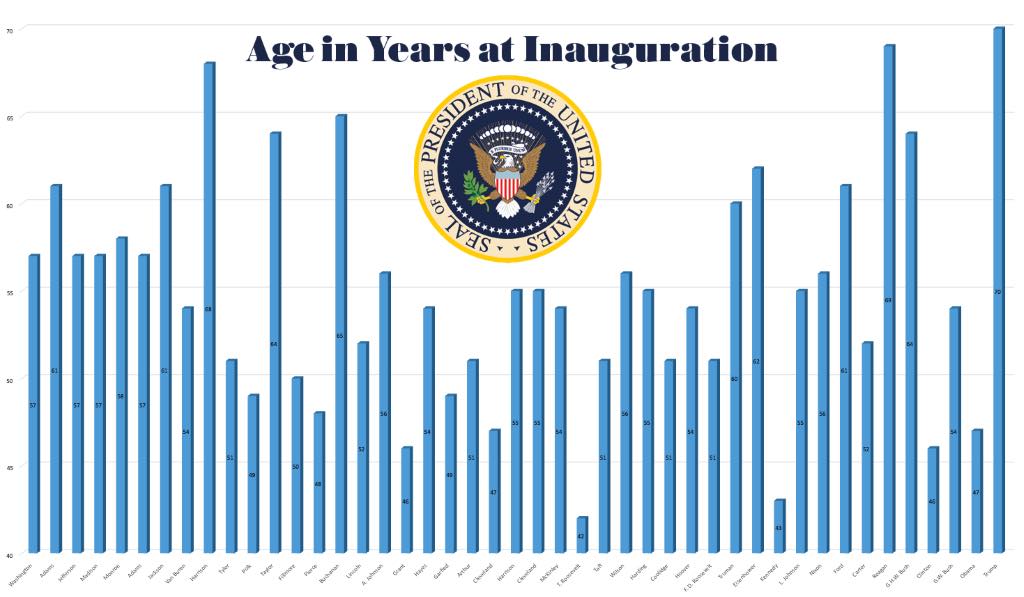

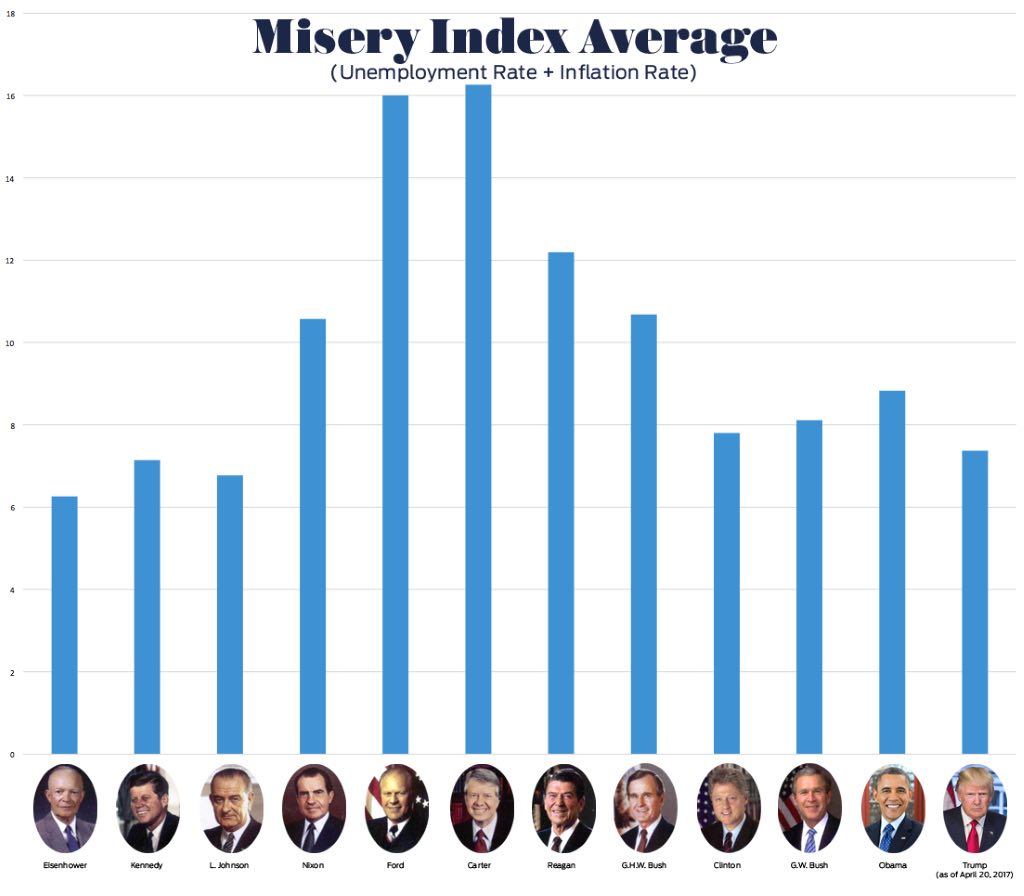

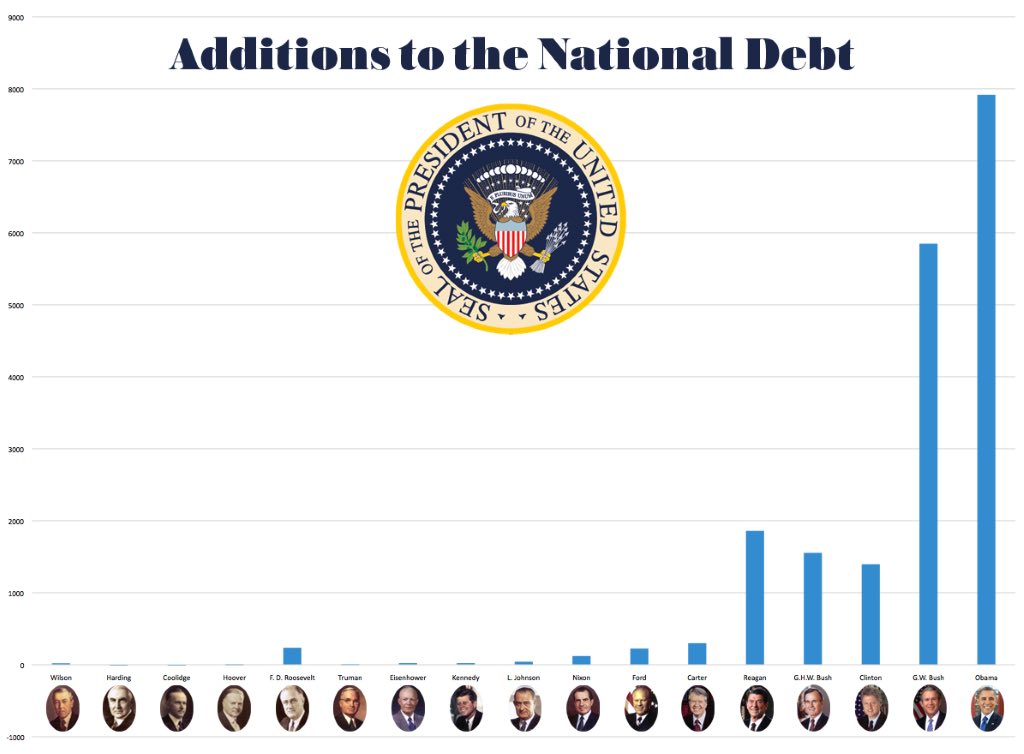

Which president issued the most executive orders? Who was the oldest at the beginning of his term? Which ones had mustaches? We tell the story of American presidents in these eight charts. Click on each one to see more detail.

Click on each chart to enlarge it. Charts created by Brian Sanchez.

The Discovery of DNA Marks a Turning Point in Science

“A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid” wasn’t the sort of title destined to grab the attention of the world’s press. Yet this article, published in Nature magazine on April 25, 1953, marked a turning point in biological science.

In the article, James Watson and Francis Crick described the structure of DNA and theorized how it faithfully reproduced itself in all living cells. Their discovery became the foundation for our modern understanding genetics and heredity.

Watson and Crick’s paper was the culmination of efforts dating back nearly a century. DNA had first been identified in 1869, and its components identified in 1919. A third scientist proved genetic material was carried on DNA in 1943. And in the 1950s, two more scientists’ studies of the DNA’s molecular structure enabled Watson and Crick to propose their double-helix configuration.

Eight years after the Nature article appeared, the Post published “The Messages of Life” by James Bonner, a professor of biology at the California Institute of Technology.

The article doesn’t show its age too obviously. Of course, biogenetics has progressed since 1961. For example, scientists know RNA does far more than simply direct enzyme production, as Bonner described. And researchers are more concerned with DNA’s role in making proteins, not enzymes.

Still, Bonner offers a clear, comprehensible explanation of the foundations of DNA studies and genetic science. If you are still uncertain what DNA does and how it affects your biological inheritance, you couldn’t do better than to read Bonner’s article.

“South of the Slot” by Jack London

Old San Francisco, which is the San Francisco of only the other day, the day before the earthquake, was divided midway by the Slot. The Slot was an iron crack that ran along the center of Market Street, and from the Slot arose the burr of the ceaseless, endless cable that was hitched at will to the cars it dragged up and down. In truth, there were two Slots, but, in the quick grammar of the West, time was saved by calling them, and much more that they stood for, The Slot. North of the Slot were the theaters, hotels and shopping district, the banks and the staid, respectable business houses. South of the Slot were the factories, slums, laundries, machine-shops, boiler-works and the abodes of the working class.

The Slot was the metaphor that expressed the class cleavage of Society, and no man crossed this metaphor, back and forth, more successfully than Freddie Drummond. He made a practice of living in both worlds and in both worlds he lived signally well. Freddie Drummond was a professor in the Sociology Department of the University of California, and it was as a professor of sociology that he first crossed over the Slot, lived for six months in the great labor ghetto and wrote The Unskilled Laborer — a book that was hailed everywhere as an able contribution to the Literature of Progress and as a splendid reply to the Literature of Discontent. Politically and economically, it was nothing if not orthodox. Presidents of great railway systems bought whole editions of it to give to their employees. A manufacturers’ association alone distributed fifty thousand copies of it. In its preachment of thrift and content it ran Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch a close second.

At first, Freddie Drummond found it monstrously difficult to get along among the working people. He was not used to their ways, and they certainly were not used to his. They were suspicious. He had no antecedents. He could talk of no previous jobs. His hands were soft. His extraordinary politeness was ominous. His first idea of the role he would play was that of a free and independent American who chose to work with his hands and no explanations given. But it wouldn’t do, as he quickly discovered. At the beginning they accepted him, very provisionally, as a freak. A little later, as he began to know his way about better, he insensibly drifted into the only role that he could play with some degree of plausibility — namely, that of a man who had seen better days, very much better days, but who was down in his luck, though, to be sure, only temporarily.

He learned many things and generalized much and often erroneously, all of which can be found in the pages of The Unskilled Laborer. He saved himself, however, after the sane and conservative manner of his kind, by labeling his generalizations as “tentative.” One of his first experiences was in the great Wilmer Cannery, where he was put on piecework making small packing-cases. A box factory supplied the parts, and all Freddie Drummond had to do was to fit the parts into a form and drive in the wire nails with a light hammer.

It was not skilled labor, but it was piecework. The ordinary laborers in the cannery got a dollar and a half a day. Freddie Drummond found the other men on the same job with him jogging along and earning a dollar and seventy-five cents a day. By the third day he was able to earn the same. But he was ambitious. He did not care to jog along, and, being unusually able and fit, on the fourth day earned two dollars. The next day, having keyed himself up to an exhausting high tension, he earned two dollars and a half. His fellow workers favored him with scowls and black looks and made remarks, slangily witty and which he did not understand, about sucking up to the boss, and pacemaking, and holding her down when the rains set in. He was astonished at their malingering on piecework, generalized about the laziness of the unskilled laborer, and proceeded next day to hammer out three dollars’ worth of boxes.

And that night, coming out of the cannery, he was interviewed by his fellow workmen, who were very angry and incoherently slangy. He failed to comprehend the motive behind their action. The action itself was strenuous. When he refused to ease down his pace and bleated about freedom of contract, independent Americanism and the dignity of toil they proceeded to spoil his pacemaking ability. It was a fierce battle, for Drummond was a large man and an athlete; but the crowd finally jumped on his ribs, walked on his face and stamped on his fingers, so that it was only after lying in bed for a week that he was able to get up and look for another job. All of this is duly narrated in that first book of his, in the chapter entitled “The Tyranny of Labor.”

A little later, in another department of the Wilmax Cannery, lumping as a fruit distributor among the women, he essayed to carry two boxes of fruit at a time and was promptly reproached by the other fruit-lumpers. It was palpable malingering; but he was there, he decided, not to change conditions, but to observe. So he lumped one box thereafter, and so well did he study the art of shirking that he wrote a special chapter on it, with the last several paragraphs devoted to tentative generalizations.

In those six months he worked at many jobs and developed into a very good imitation of a genuine worker. He was a natural linguist and he kept notebooks, making a scientific study of the workers’ slang or argot until he could talk quite intelligibly. This language also enabled him more intimately to follow their mental processes and thereby to gather much data for a projected chapter in some future book which he planned to entitle Synthesis of Working-Class Psychology.

Before he arose to the surface from that first plunge into the underworld, he discovered that he was a good actor and demonstrated the plasticity of his nature. He was himself astonished at his own fluidity. Once having mastered the language and conquered numerous fastidious qualms he found that he could flow into any nook of working-class life and fit it so snugly as to feel comfortably at home. As he said in the preface to his second book, The,Toiler, he endeavored really to know the working people; and the only possible way to achieve this was to work beside them, eat their food, sleep in their beds, be amused with their amusements, think their thoughts and feel their feelings.

He was not a deep thinker. He had no faith in new theories. All his norms and criteria were conventional. His “Thesis on the French Revolution” was noteworthy in college annals, not merely for its painstaking and voluminous accuracy, but for the fact that it was the driest, deadest, most formal and most orthodox screed ever written on the subject. He was a very reserved man, and his natural inhibition was large in quantity and steel-like in quality. He had but few friends. He was too undemonstrative, too frigid. He had no vices, nor had any one ever discovered any temptations. Tobacco he detested, beer he abhorred, and he was never known to drink anything stronger than an occasional light wine at dinner.

When a freshman he had been baptized Ice-Box by his warmer-blooded fellows. As a member of the Faculty he was known as Cold-Storage. He had but one grief, and that was Freddie. He had earned it when he played fullback on the Varsity eleven, and his formal soul had never succeeded in living it down. Freddie he would ever be, except officially, and through nightmare vistas he looked into a future when his world would speak of him as Old Freddie.

For he was very young to be a doctor of sociology — only twenty-seven, and he looked younger. In appearance and atmosphere he was a strapping big college man, smooth-faced and easy-mannered, clean and simple and wholesome, with a known record of being a splendid athlete and an implied vast possession of cold culture of the inhibited sort. He never talked shop out of class and committee-rooms, except later when his books showered him with distasteful public notice and he yielded to the extent of reading occasional papers before certain literary and economic societies.

He did everything right — too right; and in dress and comportment was inevitably correct. Not that he was a dandy. Far from it. He was a college man, in dress and carriage as like as a pea to the type that of late years is being so generously turned out of our institutions of higher learning. His handshake was satisfyingly strong and stiff. His blue eyes were coldly blue and convincingly sincere. His voice, firm and masculine, clean and crisp of enunciation, was pleasant to the ear. The one drawback to Freddie Drummond was his inhibition. He never unbent. In his football days the higher the tension of the game the cooler he grew. He was noted as a boxer, but he was regarded as an automaton, with the inhuman action of a machine judging distance and timing blows, guarding, blocking and stalling. He was rarely punished himself, while he rarely punished an opponent. He was too clever and too controlled to permit himself to put a pound more weight into a punch than he intended. With him it was a matter of exercise. It kept him fit.

As time went by Freddie Drummond found himself more frequently crossing the Slot and losing himself in South of Market. His summer and winter holidays were spent there, and, whether it was a week or a week-end, he found the time spent there to be valuable and enjoyable. And there was so much material to be gathered. His third book, Mass and Master, became a textbook in the American universities, and almost before he knew it he was at work on a fourth one, The Fallacy of the Inefficient.

Somewhere in his make-up there was a strange twist or quirk. Perhaps it was a recoil from his environment and training or from the tempered seed of his ancestors, who had been bookmen generation preceding generation; but, at any rate, he found enjoyment in being down in the working-class world. In his own world he was Cold-Storage, but down below he was Big Bill Totts, who could drink and smoke and slang and fight and be an all-around favorite. Everybody liked Bill, and more than one working-girl made love to him. At first he had been merely a good actor, but as time went on simulation became second nature. He no longer played a part, and he loved sausages — sausages and bacon, than which, in his own proper sphere, there was nothing more loathsome in the way of food.

From doing the thing for the need’s sake he came to doing the thing for the thing’s sake. He found himself regretting it as the time drew near for him to go back to his lecture room and his inhibition. And he often found himself waiting with anticipation for the dreary time to pass when he could cross the Slot and cut loose and play the devil. He was not wicked, but as Big Bill Totts he did a myriad things that Freddie Drummond would never have been permitted to do. Moreover, Freddie Drummond never would have wanted to do them. That was the strangest part of his discovery. Freddie Drummond and Bill Totts were two totally different creatures. The desires and tastes and impulses of each ran counter to the other’s. Bill Totts could shirk at a job with a clear conscience, while Freddie Drummond condemned shirking as vicious, criminal and un-American, and devoted whole chapters to condemnation of the vice. Freddie Drummond did not care for dancing, but Bill Totts never missed the nights at the various dancing clubs, such as The Magnolia, The Western Star, and The Elite; while he won a massive silver cup standing thirty inches high for being the best-sustained character at the butchers’ and meatworkers’ annual grand masked ball. And Bill Totts liked the girls, and the girls liked him, while Freddie Drummond enjoyed playing the ascetic in this particular, was open in his opposition to equal suffrage and cynically bitter in his secret condemnation of co-education.

Freddie Drummond changed his manners with his dress and without effort. When he entered the obscure little room used for his transformation scenes he carried himself just a bit too stiffly. He was too erect, his shoulders were an inch too far back, while his face was grave, almost harsh, and practically expressionless. But when he emerged in Bill Totts’ clothes he was another creature. Bill Totts did not slouch, but somehow his whole form limbered up and became graceful. The very sound of the voice was changed and the laugh was loud and hearty, while loose speech and an occasional oath were as a matter of course on his lips. Also Bill Totts was a trifle inclined to late hours, and at times, in saloons, to be good-naturedly bellicose with other workmen. Then, too, at Sunday picnics or when coming home from the show either arm betrayed a practiced familiarity in stealing around girls’ waists, while he displayed a wit keen and delightful in the flirtatious badinage that was expected of a good fellow in his class.

So thoroughly was Bill Totts himself, so thoroughly a workman, a genuine denizen of South of the Slot, that he was as class-conscious as the average of his kind, and his hatred for a scab even exceeded that of the average loyal union man. During the water-front strike Freddie Drummond was somehow able to stand apart from the unique combination, and, coldly critical, watch Bill Totts hilariously slug scab longshoremen. For Bill Totts was a dues-paying member of the Longshoremen’s Union and had a right to be indignant with the usurpers of his job. Big Bill Totts was so very big and so very able that it was Big Bill to the front when trouble was brewing. From acting outraged feelings Freddie Drummond, in the role of his other self, came to experience genuine outrage, and it was only when he returned to the classic atmosphere of the university that he was able, sanely and conservatively, to generalize upon his underworld experiences and put them down on paper as a trained sociologist should. That Bill Totts lacked the perspective to raise him above class-consciousness Freddie Drummond clearly saw. But Bill Totts could not see it. When he saw a scab taking his job away he saw red at the same time and little else did he see. It was Freddie Drummond, irreproachably clothed and comported, seated at his study desk or facing his class in Sociology 17, who saw Bill Totts and all around Bill Totts, and all around the whole scab and union-labor problem and its relation to the economic welfare of the United States in the struggle for the world-market. Bill Totts really wasn’t able to see beyond the next meal and the prize-fight the following night at the Gayety Athletic Club.

It was while gathering material for “Women and Work” that Freddie received his first warning of the danger he was in. He was too successful at living in both worlds. This strange dualism he had developed was, after all, very unstable, and as he sat in his study and meditated he saw that it could not endure. It was really a transition stage; and if he persisted he saw that he would inevitably have to drop one world or the other. He could not continue in both. And as he looked at the row of volumes that graced the upper shelf of his revolving bookcase, his volumes, beginning with his Thesis and ending with “Women and Work,” he decided that that was the world he would hold on to and stick by. Bill Totts had served his purpose, but he had become a too-dangerous accomplice. Bill Totts would have to cease.

Freddie Drummond’s fright was due to Mary Condon, president of the International Glove-Workers’ Union No. 974. He had seen her first from the spectators’ gallery at the annual convention of the Northwest Federation of Labor, and he had seen her through Bill Totts’ eyes, and that individual had been most favorably impressed by her. She was not Freddie Drummond’s sort at all. What if she were a royal-bodied woman, graceful and sinewy as a panther, with amazing black eyes that could fill with fire or laughter-love, as the mood might dictate? He detested women with a too-exuberant vitality and a lack of — well, of inhibition. Freddie Drummond accepted the doctrine of evolution because it was quite universally accepted by college men, and he flatly believed that man had climbed up the ladder of life out of the weltering muck and mess of lower and monstrous organic things. But he was a trifle ashamed of this genealogy. Wherefore, probably, he practiced his iron inhibition and preached it to others, and preferred women of his own type who could shake free of this bestial and regrettable ancestral line and by discipline and control emphasize the wideness of the gulf that separated them from what their dim forebears had been.

Bill Totts had none of these considerations. He had liked Mary Condon from the moment his eyes first rested on her in the convention hall, and he had made it a point, then and there, to find out who she was. The next time he met her, and quite by accident, was when he was driving an express wagon for Pat Morrissey. It was in a lodging house in Mission Street, where he had been called to take a trunk into storage. The landlady’s daughter had called him and led him to the little bedroom, the occupant of which, a glovemaker, had just been removed to a hospital. But Bill did not know this. He stooped, upended the trunk, which was a large one, got it on his shoulder and struggled to his feet with his back toward the open door. At that moment he heard a woman’s voice.

“Belong to the union?” was the question asked.

“Belong to the union?” was the question asked.

“Aw, what’s it to you?” he retorted. “Run along now, an’ git outs my way. I wants turn ‘round.”

The next he knew, big as he was, he was whirled half around and sent reeling backward, the trunk overbalancing him, till he fetched up with a crash against the wall. He started to swear, but at the same instant found himself looking into Mary Condon’s flashing, angry eyes.

“Of course I b’long to the union,” he said. “I was only kiddin’ you.”

“Where’s your card?” she demanded in businesslike tones. “In my pocket. But I can’t git it out now. This trunk’s too damn heavy. Come on down to the wagon an’ I’ll show it to you.”

“Put that trunk down,” was the command.

“What for? I got a card, I’m tellin’ you.”

“Put it down, that’s all. No scab’s going to handle that trunk. You ought to be ashamed of yourself, you big coward, scabbing on honest men. Why don’t you join the union and be a man?”

Mary Condon’s color had left her face and it was apparent that she was in a white rage.

“To think of a big man like you turning traitor to his class. I suppose you’re aching to join the militia for a chance to shoot down union drivers the next strike. You may belong to the militia already, for that matter. You’re the sort — ”

“Hold on now; that’s too much I — ” Bill dropped the trunk to the floor with a bang, straightened up and thrust his hand into his inside coat pocket. “I told you I was only kiddin’. There, look at that.”

It was a union card properly enough.

“All right, take it along,” Mary Condon said. “And the next time don’t kid.”

Her face relaxed as she noticed the ease with which he got the big trunk to his shoulder and her eyes glowed as they glanced over the graceful massiveness of the man. But Bill did not see that. He was too busy with the trunk.

The next time he saw Mary Condon was during the laundry strike. The laundry workers, but recently organized, were green at the business, and had petitioned Mary Condon to engineer the strike. Freddie Drummond had had an inkling of what was coming and had sent Bill Totts to join the union and investigate. Bill’s job was in the washroom, and the men had been called out first that morning in order to stiffen the courage of the girls; and Bill chanced to be near the door to the mangle-room when Mary Condon started to enter. The superintendent, who was both large and stout, barred her way. He wasn’t going to have his girls called out and he’d teach her a lesson to mind her own business. And as Mary tried to squeeze past him he thrust her back with a fat hand on her shoulder. She glanced around and saw Bill.

“Here you, Mr. Totts,” she called. “Lend a hand. I want to get in.”

Bill experienced a startle of warm surprise. She had remembered his name from his union card. The next moment the superintendent had been plucked from the doorway, raving about rights under the law, and the girls were deserting their machines. During the rest of that short and successful strike, Bill constituted himself Mary Condon’s henchman and messenger, and when it was over returned to the university to be Freddie Drummond and to wonder what Bill Totts could see in such a woman.

Freddie Drummond was entirely safe, but Bill had fallen in love. There was no getting away from the fact of it, and it was this fact that had given Freddie Drummond his warning. Well, he had done his work and his adventures could cease. There was no need for him to cross the Slot again. All but the last three chapters of his latest, Labor Tactics and Strategy, was finished, and he had sufficient material on hand adequately to supply those chapters.

Another conclusion he arrived at was that, in order to sheet anchor himself as Freddie Drummond, closer ties and relations in his own social nook were necessary. It was time that he was married, anyway, and he was fully aware that if Freddie Drummond didn’t get married Bill Totts assuredly would, and the complications were too awful to contemplate. And so enters Catherine Van Vorst. She was a college woman herself, and her father, the one wealthy member of the faculty, was the head of the philosophy department. It would be a wise marriage from every standpoint, Freddie Drummond concluded when the engagement was entered into and announced. In appearance, cold and reserved, aristocratic and wholesomely conservative, Catherine Van Vorst, though warm in her way, possessed an inhibition equal to Drummond’s.

All seemed well with him, but Freddie Drummond could not quite shake off the call of the underworld, the lure of the free and open, of the unhampered, irresponsible life South of the Slot. As the time of his marriage approached he felt that he had indeed sowed wild oats, and he felt, moreover, what a good thing it would be if he could have but one wild fling more, play the good fellow and the wastrel one last time ere he settled down to gray lecture rooms and sober matrimony. And, further to tempt him, the very last chapter of Labor Tactics and Strategy remained unwritten for lack of a trifle more of essential data which he had neglected to gather.

So, Freddie Drummond went down for the last time as Bill Totts, got his data, and, unfortunately, encountered Mary Condon. Once more installed in his study it was not a pleasant thing to look back upon. It made his warning doubly imperative. Bill Totts had behaved abominably. Not only had he met Mary Condon at the Central Labor Council, but he had stopped in at a creamery with her, on the way home, and treated her to oysters. And before they parted at her door his arms had been about her and he had kissed her on the lips and kissed her repeatedly. And her last words in his ear, words uttered softly with a catchy sob in the throat that was nothing more nor less than a love-cry, were, “Bill — dear, dear Bill.”

Freddie Drummond shuddered at the recollection. He saw the pit yawning for him. He was not by nature a polygamist, and he was appalled at the possibilities of the situation. It would have to be put an end to, and it would end in one only of two ways: either he must become wholly Bill Totts and be married to Mary Condon, or he must remain wholly Freddie Drummond and be married to Catherine Van Vorst. Otherwise, his conduct would be horrible and beneath contempt.

In the several months that followed, San Francisco was torn with labor strife. The unions and the employers’ associations had locked horns with a determination that looked as if they intended to settle the matter one way or the other for all time. But Freddie Drummond corrected proofs, lectured chases and did not budge. He devoted himself to Catherine Van Vorst and day by day found more to respect and admire in her — nay, even to love in her. The streetcar strike tempted him, but not so severely as he would have expected; and the great meat strike came on and left him cold. The ghost of Bill Totts had been successfully laid, and Freddie Drummond with rejuvenescent zeal tackled a brochure, long-planned, on the topic of Diminishing Returns.

The wedding was two weeks off when, on one afternoon, in San Francisco, Catherine Van Vorst picked him up and whisked him away to see a Boys’ Club recently instituted by the settlement workers with whom she was interested. They were in her brother’s machine, but they were alone except for the chauffeur. At the junction with Kearny Street, Market and Geary Streets intersect like the sides of a sharp-angled letter V. They, in the auto, were coming down Market with the intention of negotiating the sharp apex and going up Geary. But they did not know what was coming down Geary, timed by Fate to meet them at the apex. While aware from the papers that the meat strike was on and that it was an exceedingly bitter one, all thought of it at that moment was farthest from Freddie Drummond’s mind. Was he not seated beside Catherine? And besides, he was carefully expounding to her his views on settlement work — views that Bill Totts’ adventures had played a part in formulating.

Coming down Geary Street were six meat wagons. Beside each scab driver sat a policeman. Front and rear, and along each side of this procession, marched a protecting escort of one hundred police. Behind the police rear-guard, at a respectful distance, was an orderly but vociferous mob several blocks in length, that congested the street from sidewalk to sidewalk. The Beef Trust was making an effort to supply the hotels and, incidentally, to begin the breaking of the strike. The St. Francis had already been supplied at a cost of many broken windows and broken heads, and the expedition was marching to the relief of the Palace Hotel.

All unwitting, Drummond sat beside Catherine talking settlement work as the auto, honking methodically and dodging traffic, swung in a wide curve to get around the apex. A big coal wagon, loaded with lump coal and drawn by four huge horses, just debouching from Kearny Street as though to turn down Market, blocked their way. The driver of the wagon seemed undecided, and the chauffeur, running slow but disregarding some shouted warning from the policemen, swerved the auto to the left, violating the traffic rules in order to pass in front of the wagon.

At that moment Freddie Drummond discontinued his conversation. Nor did he resume it again, for the situation was developing with the rapidity of a transformation scene. He heard the roar of the mob at the rear and caught a glimpse of the helmeted police and the lurching meat wagons. At the same moment, laying on his whip and standing up to his task, the coal-driver rushed horses and wagon squarely in front of the advancing procession, pulled the horses up sharply and put on the brake. Then he made his lines fast to the brake-handle and sat down with the air of one who had stopped to stay. The auto had been brought to a stop, too, by his big, panting leaders.

Before the chauffeur could back clear, an old Irishman, driving a rickety express wagon and lashing his one horse to a gallop, had locked wheels with the auto. Drummond recognized both horse and wagon, for he had driven them often himself. The Irishman was Pat Morrissey. On the other side a brewery wagon was locking with the coal wagon, and an east-bound Kearny Street car, wildly clanging its gong, the motorman shouting defiance at the crossing policemen, was dashing forward to complete the blockade. And wagon after wagon was locking and blocking and adding to the confusion. The meat wagons halted. The police were trapped. The roar at the rear increased as the mob came on to the attack, while the vanguard of the police charged the obstructing wagons.

“We’re in for it,” Drummond remarked coolly to Catherine.

“Yes,” she nodded with equal coolness. “What savages they are!”

His admiration for her doubled on itself. She was indeed his sort. He would have been satisfied with her even if she had screamed and clung to him, but this — this was magnificent. She sat in that storm center as calmly as if it had been no more than a block of carriages at the opera.

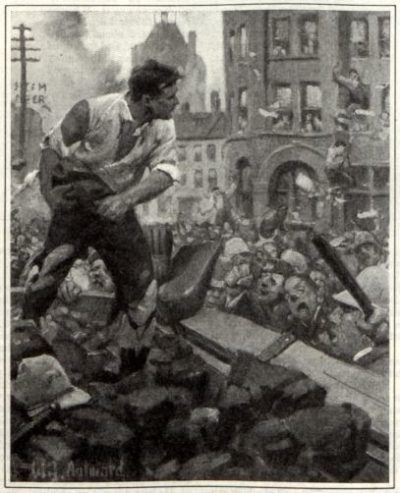

The police were struggling to clear a passage. The driver of the coal wagon, a big man in shirt sleeves, lighted a pipe and sat smoking. He glanced down complacently at a captain of police who was raving and cursing at him, and his only acknowledgment was a shrug of the shoulders. From the rear arose the rat-tat-tat of clubs on heads and a pandemonium of cursing, yelling and shouting. A violent accession of noise proclaimed that the mob had broken through and was dragging a scab from a wagon. The police captain was reinforced from his vanguard and the mob at the rear was repelled. Meanwhile, window after window in the high office building on the right had been opened and the class-conscious clerks were raining a shower of office furniture down on the heads of police and scabs. Waste-baskets, ink-bottles, paper-weights, typewriters — anything and everything that came to hand was filling the air.

A policeman, under orders from his captain, clambered to the lofty seat of the coal wagon to arrest the driver. And the driver, rising leisurely and peacefully to meet him, suddenly crumpled him in his arms and threw him down on top of the captain. The driver was a young giant, and when he climbed on top his load and poised a lump of coal in both hands a policeman, who was just scaling the wagon from the side, let go and dropped back to earth. The captain ordered half a dozen of his men to take the wagon. The teamster, scrambling over the load from side to side, beat them down with huge lumps of coal.

The crowd on the sidewalks and the teamsters on the locked wagons roared encouragement and their own delight. The motorman, smashing helmets with his controller-bar, was beaten into insensibility and dragged from his platform. The captain of police, beside himself at the repulse of his men, led the next assault on the coal wagon. A score of police were swarming up the tall-sided fortress. But the teamster multiplied himself. At times there were six or eight policemen rolling on the pavement and under the wagon. Engaged in repulsing an attack on the rear end of his fortress the teamster turned about to see the captain just in the act of stepping on to the seat from the front end. He was still in the air and in most unstable equilibrium when the teamster hurled a thirty-pound lump of coal. It caught the captain fairly on the chest and he went over backward, striking on a wheeler’s back, tumbling to the ground and jamming against the rear wheel of the auto.

Catherine thought he was dead, but he picked himself up and charged back. She reached out her gloved hand and patted the flank of the snorting, quivering horse. But Drummond did not notice the action. He had eyes for nothing save the battle of the coal wagon, while somewhere in his complicated psychology one Bill Totts was heaving and straining in an effort to come to life. Drummond believed in law and order and the maintenance of the established; but this riotous savage within him would have none of it. Then, if ever, did Freddie Drummond call upon his iron inhibition to save him. But it is written that the house divided against itself must fall. And Freddie Drummond found that he had divided all the will and force of him with Bill Totts, and between them the entity that constituted the pair of them was being wrenched in twain.