This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

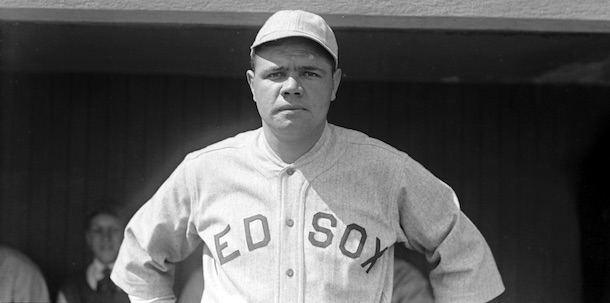

In talking about himself, the Babe wishes to make it clear that he has been both bad and good, and that his real name is George Herman Ruth, and not Ehrhardt, as has been often stated in the question-and-answer departments of newspapers. The late Jack Dunn, owner and manager of the Baltimore ball club, called him George until the players had unanimously decided on “Babe,” and made it stick.

“In those days,” Ruth explains, “Dunn was always digging up youngsters for tryouts with his ball club. When

Brother Gilbert and myself came out of Jack’s once after they had signed me to a baseball contract 18 years ago, the players saw me from a distance. ‘There’s another one of Dunn’s babies,’ one of them remarked. The minute I put on a uniform they called me Babe and, in baseball, I have never known any other name. I’m not kicking, though. I rather like it. I was such a big fellow that the nickname of Babe struck the other boys as funny. I guess it would still be funny if we hadn’t all got used to it.”

“How long do you expect to play ball?” he was asked.

“I figure that about two more years ought to do me, but you can’t tell about that. You know how it is. Clark Griffith may have been right when he said that no ballplayer ever voluntarily quits the game until they cut the uniform to him. Anyway, I won’t be in there until I trip on my whiskers and the boys begin feeling sorry for me. I won’t have to do that.”

“What’s the most money you ever made in one year, Babe?”

He rubbed his freshly shaven face in an effort to remember. “About $130,000 — that is, counting baseball salary, exhibition work, stage appearances, syndicate writing, and so on. And, boy,” he chuckled, “you ought to see how I managed to scatter that chunk.”

“Did you ever try to figure how much you have earned altogether since you began playing professional baseball 18 years ago?”

“Oh, my average has been better than $50,000 a year. I’ve made at least a million dollars. Threw away more than half of it too. Had a lot of fun, though.”

“Did you have any aim in life, or any particular thought to the future, when you started out as a ballplayer?”

“No, of course I didn’t. I just wanted to play ball. I still like to play, even if it’s just for the fun of it. When I got my first job it seemed funny to me that anybody would pay me money to play ball.”

“Which do you get the most thrill out of — your pitching or your hitting?”

“That’s hard to say,” he replied after some thought. “I don’t believe I could ever get any more thrill than I did in pitching those scoreless innings in the 1918 World Series back in Boston. Still, anybody gets a big kick out of taking a cut at that ball and hitting it on the nose. Anyway, I know the public gets a bigger kick out of seeing a fellow hit ’em than in seeing him pitch ’em. Why, take a 60-year-old golfer, for instance. Nothing in the world gives him such a thrill as clipping that golf ball on the button with a full swing. They’ll tell you the science of the fine shots is what counts, but that’s all baloney. What counts in their lives is socking that ball and giving it a ride.

“Now, the records will show that I was a pretty good pitcher. You never hear much about that, though… The kids know me as a home-run slugger.”

During the past World Series in 1931 Ruth sat beside the writer in the grandstand at St. Louis, experting on the big games. “Mr. Ruth,” interrupted a pleasant-voiced young lady, “will you please autograph this program for me? My uncle was a ballplayer and — ”

“OK,” said the Babe, scrawling his familiar signature and passing it back over his shoulder. “Now I’m in for it,” he confided out of the corner of his mouth; “they’ll keep this up for an hour.”

And they did. Protesting ushers were swept aside in the rush. The autograph seekers were in attacking formation. They brought programs, rain checks, toy bats, notebooks, hatbands — everything — to be decorated with the Ruth signature. After a half hour his hand was so badly cramped that he demanded a rest.

“First thing you know,” he said, “ some bird will be asking me to sign his socks.”

“Listen,” Ruth finally warned his increasing admirers, “I’m going to stop when play starts. You know, I want to see some of this ball game myself.” That merely served to accelerate the rush.

The amplifiers finally announced the first batter.

“No, that’s all,” the Babe resolutely denied the next applicant. “No more till tomorrow. None after the game either.”

“Can’t you sign this baseball, Mr. Ruth?” a rather weary voice spoke behind him.

“No, no. I turned down the others. Come out before the game tomorrow. I’ve been doing this for an hour now. Got to see the ball game.”

“I’m sorry,” explained the voice. “I had to come up on crutches and just got here.”

“What’s that — crutches? Well, that’s different.” His big hand reached back for the ball and he carefully inscribed his name. “Sorry you had so much trouble. You’re welcome. That’ll get me in trouble sure,” came in an undertone from the corner of his mouth.

“Won’t you please sign this score card?” immediately spoke a feminine voice. “My father owns a baseball club out West. Won the pennant.”

“All right. Hand it over.” And down went the signature, with the added comment: “Good luck to the Indians.”

With these two exceptions he stuck to his refusal and called it a day.

Today Ruth looks back on St. Mary’s, the orphanage where he was raised, as the real home of his early boyhood. The memories of it are very dear to him. “You know,” he said, during a later lull in the ball game, “I was not an orphan when I went to St. Mary’s. My parents were living, but they were very poor. I went to that school the first time when I was only 6 years old. The second time they sent me I stayed there. Oh, yes, I guess I was a truant, all right, and needed to be taken there, but many boys who went there were not bad boys or truants. They were sent by their parents to St. Mary’s just to learn a trade. It’s a great school.”

“What trade did they select for you?” I asked him.

“Oh, I was a shirt maker — darn good one too. That’s why they can’t fool me about shirts to this day. I know how they are cut and how the parts are put together. I worked at an electrical machine which stitches the parts of a shirt together. I was the best one in the school,” he added, with a touch of pride.

The boys at St. Mary’s were not long in discovering that George Ruth, as they knew him then, could throw a baseball harder and hit one farther than any other kid in school. Ruth is very much in doubt as to what position he played at first. “Oh, I just played ball and played in any position they’d let me. I’ve been outfielder, infielder, catcher, and pitcher. It made no difference to me. You know how it is with boys.”

In time Ruth developed so much prowess as a pitcher that he was assigned to that job regularly. It was his remarkable showing as a left-handed pitcher that influenced Brother Gilbert to speak to Jack Dunn, owner and manager of the Bal- timore club, about him. “You can bet I will never forget that day,” says Ruth. “Boy, that was a thrill! After Jack Dunn had talked to me for a few minutes they gave me a sort of tryout in the yard. I guess Jack decided that I had something.”

Brother Gilbert explained to Ruth that boys played ball for fun, but that he was now taking a man’s job that called for business arrangements. “Mr. Dunn has agreed to pay you $600 for the six months of the playing season,” Brother Gilbert told Ruth. “That is $100 a month, or about $25 a week. Would you be satisfied with that, George?”

Ruth says that he would have been satisfied to play baseball for nothing, as long as he had a place to eat. Six hundred dollars was about the largest sum of money his mind had ever contemplated. “I got a big kick out of winning my first World Series game,” he says. “It was another kick when I established that record of the most scoreless innings pitched in a World Series. And you know my feelings when I hung up that home-run record for the Yankees. But I’m telling you, the biggest kick I ever got was when I walked out on that field that day and told the other boys that I had signed a contract and was now a real, honest-to-goodness professional ballplayer and was going to get paid for it.”

Babe’s recollection is that Manager Dunn raised his salary at the end of the second month, making his total for the season $1,800. Never having known anything about the value of money and never having had possession of more than two or three dollars at a time, this $300 a month seemed to the Babe an enormous sum. The players on the Baltimore club found this big, gawky youth one of the most generous-hearted souls they had ever met. He would give them his shirt if they wanted it. If he had $100 in his pocket, he would bet it on a horse race just as quickly as if the amount had been $5. The Oriole players hated to see him go, but they knew that he was bound to go sooner or later. And they were right.

Before the end of that season — 1914 — Ruth had joined the Red Sox. In Boston they gave him a contract calling for $3,500 a season. Besides learning the finer tricks of baseball, Ruth wanted to learn what the boys in fast company did for amusement in their o hours. His education in that respect was rapid indeed. e world had opened up for the Babe and he wanted to examine its inside to see what made it tick.

Probably the greatest sense of freedom and well-being that Ruth had ever enjoyed up to that time was his first experience as a guest in the hotels patronized by the Baltimore club. The elevators fascinated him. He rode them up and down for the sheer joy of it. His first adventure into the fast life was the acquisition of a bicycle, obtained temporarily from a messenger. As a consequence, he got the habit of sneaking off for a trip of exploration occasionally, much to the worry of Manager Dunn. Finally Dunn called a stern halt to Babe’s excessive riding on elevators and bicycles.

One of the early uses for money as discovered by the Babe was an unrestrained indulgence in hot dogs. Before, during, and after the games he bought and consumed them. He would now but for a rigid diet decree that he reluctantly obeys. After Ruth became famous, one of his attacks of indigestion was attributed to his consumption of 11 hot dogs and three bottles of soda pop in one afternoon at the ball park.

One day, in a batting practice just before the game, Ruth hit a liner that cleared the right-field fence like a bullet. The grandstand buzzed with the wonder of it. Long before that, however, the players had been talking about this natural hitter with such perfect form. To the wonder of experts, this big kid could take a full swing with a bat, gripping the handle at the extreme small end, and time the ball with as much precision as if he had chopped it.

Up to that time it had been the batting theory that a full swing lessened the hitter’s accuracy and gave the pitcher all the advantage. There were a few exceptions, but most of the great hitters used the short or chop swing, and stepped forward to meet the ball in front of the plate. By taking a chop swing they could keep their eye on the ball all the time and not be thrown off balance by a violent swing. Ruth upset all that. His perfect eyesight, his sense of timing and his muscles were so coordinated that he could take a shoestring swing and throw the full weight of his big body behind the wallop with precision. Ruth’s demonstration of such power in natural rhythm was the forerunner of the home-run fad that made a revolutionary change in the game. Others began trying it, and even the kids on the sandlots caught the fence-busting craze. Even so, it was a long time before the best baseball minds thought of Ruth as a regular batter. He was regarded as a freak. They marveled at the terrific force of his drives, but continued to think of him as a pitcher rather than as a batter.

Though he developed into a masterful pitcher and holds the record of having pitched 29 consecutive scoreless innings in a World Series (1916 and 1918), Ruth was not an object of hero worship, nor did he come into riches, until he began to hit his home runs.

In 1918, Ed Barrow, a veteran baseball man, was manager of the Boston Red Sox. In Ruth he knew that he had a great pitcher, but when the Babe began to hit home runs with marked regularity in 1918, Barrow saw that he might be more effective as a hitter than as a defensive player. Also his keen mind had noted the eagerness of the fans to see Ruth bat, even when he was pitching masterfully.

Before the next season came around, the farseeing Barrow had made up his mind. The season of 1919 found Babe Ruth one of the regular out elders. All baseball watched the experiment with keen interest, a few openly doubting its success. Ruth had established a world’s record by pitching. Still, Barrow had to consider that a pitcher would be inactive about four days out of five. “Can’t keep a man like that on the bench,” decided the manager, and he was wise.

In appreciation of his work as a pitcher as well as a hitter, the Boston club raised Ruth’s salary from $7,000 to $10,000 and gave him the three-year contract. That was the contract that the New York Yankees eventually bought.

In the spring of 1919, Ruth hit 29 home runs, a new world’s record. To appreciate the impact of that accomplishment, you need only look back six years earlier. In 1913 when Frank Baker of the Athletics had hit 12 home runs, it was regarded such a marvelous performance that he earned the sobriquet of Home Run Baker.

Ruth’s longest home run of record was made in Tampa, Florida, in an exhibition game between the New York Giants and the Boston club in the spring of 1919. This game was played in a race-track inclosure. The ball hit by Ruth not only went over the outer circle of the track but cleared the distant barns and fell into a sort of park in front of the Tampa Bay Hotel. The distance covered by this long drive was so unbelievable that a group of Boston and New York writers got a tape line and measured it. From the home plate to the point where the ball struck the ground was exactly 508 feet.

At the end of the 1919 season, in which Babe Ruth had shattered all home-run records, Harry Frazee, owner of the Red Sox, was in financial straits. He agreed to turn Ruth’s contract over to the New York club for $100,000 in cash.

When the deal had been finally consummated and Ruth had become the property of the New York club, practically every newspaper in the big city carried the news on the front page under glaring headlines. New York dearly loves a hero, and here was one made to order. The fact that much was expected of him and that the eyes of a great city were upon his every move did not in the least disturb Mr. Ruth. Reporting to Manager Miller Huggins for spring practice, Ruth began hitting home runs in the exhibition games and kept it up right to the end of the season. Long before the summer was over the Bambino, as Ruth came to be called by his Italian admirers, and then by everybody, had passed his world’s record of 29 home runs and was onto a new mark. At the end of the 1920 season, Ruth had astounded all baseball by making 54 home runs. This was an average of a fraction more than one for every three games.

With his mad rampage of home-run hitting, attendance at the Yankee games increased in jumps. A few years earlier, it was considered worthy of note for a major-league ball club to play to more than 500,000 spectators in a season. With the coming of Ruth, the Yankees eventually passed the 1 million mark.

Flush with box office receipts, the owners bought a big plot of ground in the Bronx across the river from the Polo Grounds and built a stadium costing more than $2 million. Though this structure is officially called the Yankee Stadium, it is frequently, and justly, referred to as The House That Ruth Built. An architectural feature of great satisfaction to the Babe was the close proximity of the kitchen, where the hot dogs are concocted, to the players’ bench.

The Yankee owners, in appreciation of what Ruth had done for the club, voluntarily raised his salary to $30,000 for the season of 1921.

—“And Along Came Ruth” (4-part series) by Bozeman Bulger, November–December 1931

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now