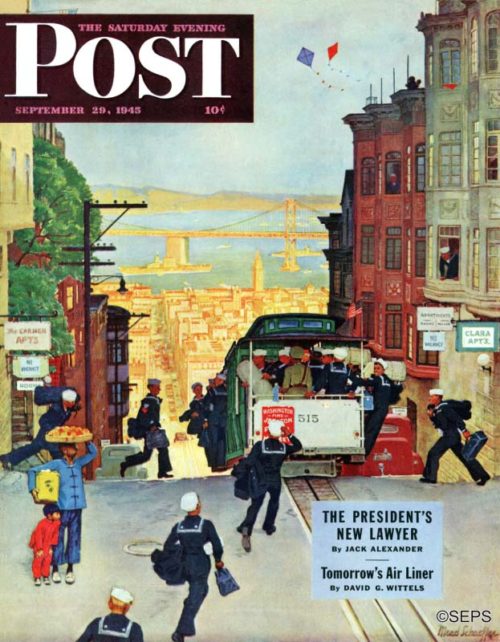

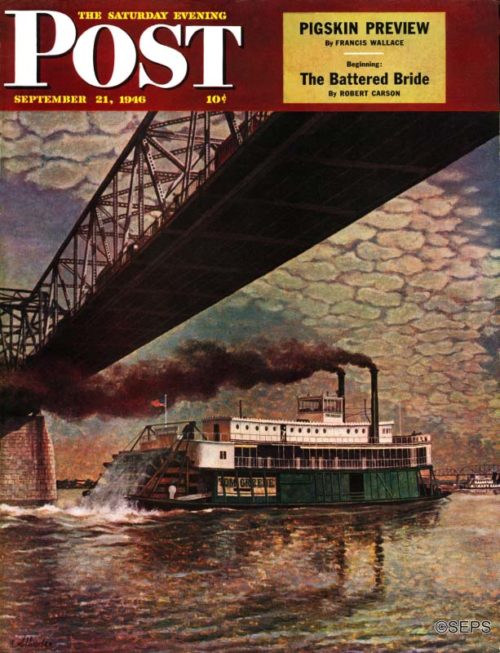

Cover Gallery: Bridal Wave

June means the start of wedding season. These Post covers show beautiful brides of the twentieth century.

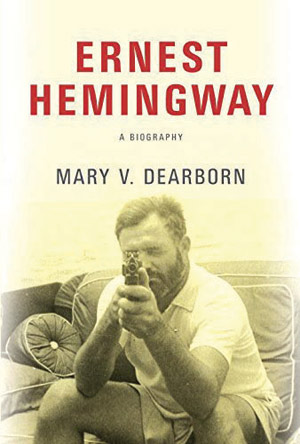

J. C. Leyendecker

June 21, 1913

In this painting by prolific artist J.C. Leyendecker, he shows a solemn couple having their photograph taken. Leyendecker illustrated the nuptial moments of other pairs, including Romeo and Juliet and Henry V and Catherine Valois. It appears this couple has got the “wedded” part down, if not the “bliss.”

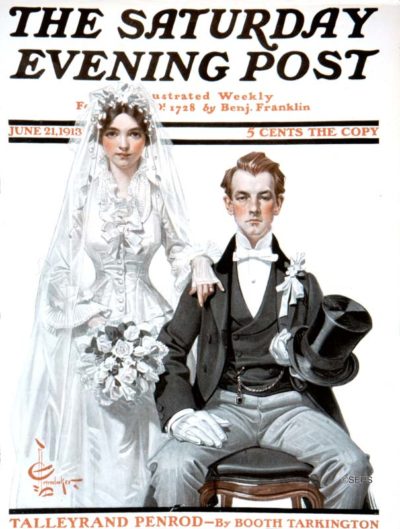

July 26, 1930

J.C. Leyendecker

Catherine of Valois married Henry V in June of 1420 and later gave birth to Henry VI. Henry V died shortly after his son’s birth, leaving the young Catherine a widow and her infant son the King of England.

Albert W. Hampson

June 5, 1937

The groom doesn’t look too happy about this scenario. Given the line of enthusiastic groomsmen, the bride may not have enough energy for the honeymoon.

John LaGatta

June 24, 1939

LaGatta had an uncanny knack for translating from model to canvas an appreciation and sensual perspective of the female figure. LaGatta began his artistic process by sketching the models in charcoal and pastels and then would almost always refine his interpretation into an oil painting. His subjects were sophisticated, upper-class men and women with long graceful figures and with classic clothing designs. His images gave the impression that the models didn’t have a care in the world, as in this 1939 cover of a couple running off after their wedding ceremony.

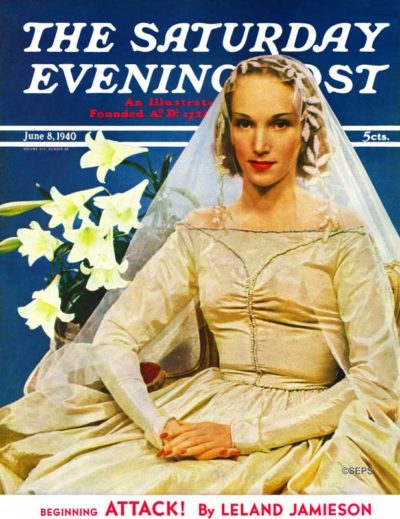

Wynn Richards

June 8, 1940

This 1940 bridal photograph was Wynn Richards’ one and only cover for the Saturday Evening Post. Richards was born “Martha Kinman Wynn” before marrying Dorsey Eugene Richards, according to her biography.. She opened her own photography studio in 1919, but left the business to a friend after a social scandal that involved her taking nude portraits of a local school teacher. Richards divorced her husband and left their son with his grandmother before opening a new portrait studio a few years later. Initially signing her work “Matsy Wynn Richards,” she learned that revealing her gender could hinder her career, and changed her signature to “Wynn Richards.” Richard’s work mostly appeared in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Mademoiselle magazine.

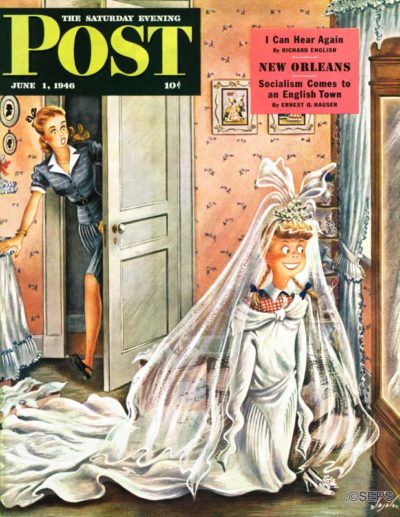

Constantin Alajalov

June 1, 1946

[From the editors of the June 1, 1946 issue of the Post] Just after Constantin Alajalov finished his kid-sister painting, he set out from New York for Florida, to work on other cover assignments. The artist went by automobile, and sent back a short report on his three-day journey. The highways are full of displaced persons at the moment, sorting themselves out after the great disruption of war, and we think Alajalov’s account is a thumbnail picture of America in Transition. “The first day,” he wrote, “I picked up a corporal just back from Tokyo, hitch-hiking to Alabama to marry a girl there. The second day I picked up a marine hitch-hiking to Jacksonville, Florida, to get his wife. The third day I picked up a sailor who was going to Miami for any girl he could get.”

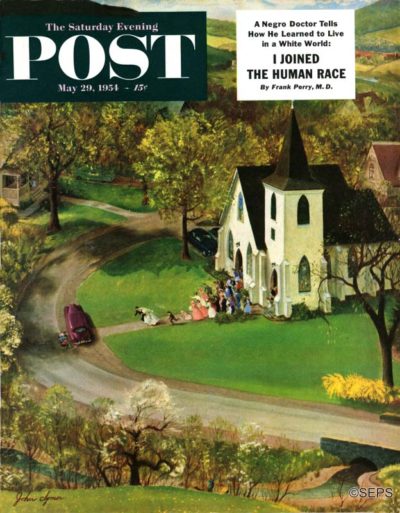

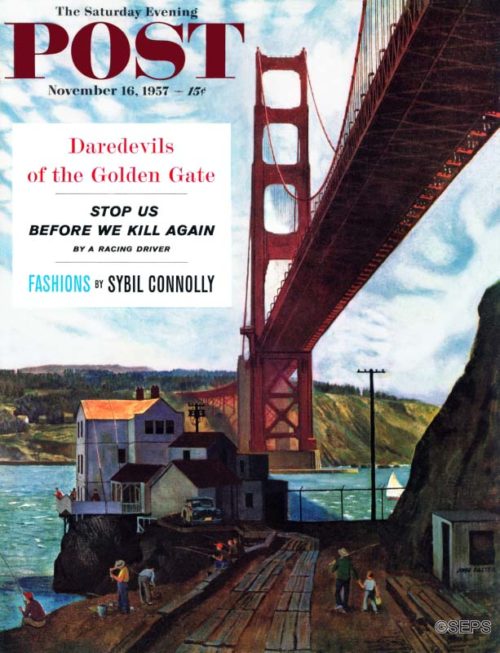

May 29, 1954

John Clymer

[From the editors of the May 29, 1954 Post] Away go the newly-marrieds into their brave new world and thank heaven it isn’t raining. John Clymer is nice about weather; on his covers it hardly ever rains. That church, says Clymer, is located in one state and the landscape in another state, and the honeymoon will take place in the state of bliss always visited on such trips.

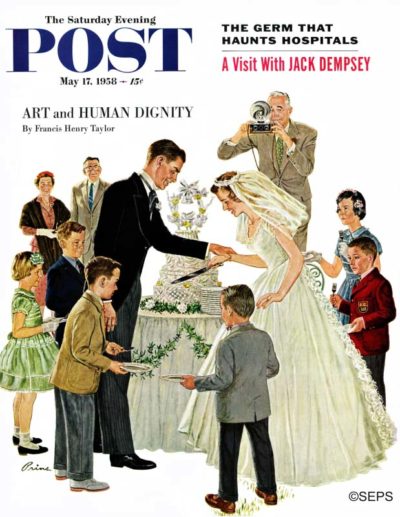

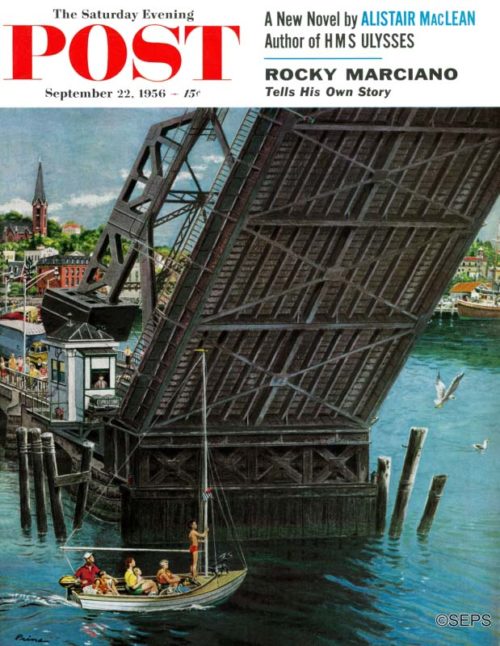

May 17, 1958

Ben Prins

[From the editors of the May 17, 1958 Post] Here come the bride and groom to carve the cake. Two-handed carving isn’t an efficient way to dismember food, but He and She have just become One and this is the tender symbol of their unity. They probably aren’t hungry; in a day or two food will become attractive, but right now they are not of this world, they are up in the clouds, in a state of bliss where folks subsist on love alone. Conversely, those youngsters have their feet on the ground and their eyes on the cake. Oh, the girls may save a few crumbs to put under their pillows to incite romantic dreaming, but the boys will put their cake where it belongs, and let’s hope they don’t consume enough to turn dreams into nightmares. Well, a toast to artist Ben Prins’ newlyweds: bon voyage, all the way through life!

North Country Girl: Chapter 2 — What I Didn’t Learn in Kindergarten

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I had started kindergarten age four on the army base in Hawaii. My father, a captain, had wrangled this early admission to get me out of my mother’s hair while she coped with a new baby. After a several month gap in my education while we lived with my grandparents, I was sent off to Cobb Elementary School as soon as we moved into the Woodland house, in the middle of the school year. I was the new kid, the smallest kid, and a year younger than most of my classmates. The old maid teacher (the Duluth Board of Education required that all elementary teachers be grey or white haired spinsters) carefully instructed me that if I had to throw up I should not run around the room but stay in one place, the only useful thing I learned in kindergarten. I painted at the easel, sang Old McDonald, pressed my hand into a disc of wet clay to create a Mother’s Day present, and made not a single friend. This would have distressed my mother if she had had the time to notice; she spent the entire day wrestling with a skinny, shrieking, thrashing toddler who fought tooth and claw against sleeping and eating and everything else.

I was friendless, but not unhappy. I had my books and my dolls and a baby sister to boss around. And every day at 3, I had The Bozo Show on our black and white TV. When Bozo wasn’t showing cartoons, but clowning around in the studio, I went back to my book while Lani rampaged through the house. Neither of us were interested in Bozo’s puerile antics or the tedium of listening to the dozens of snotty-nosed kids squashed on bleachers trying to remember their own names for the camera.

At that time we only had two TV stations in Duluth, neither of which was particularly dedicated to children’s programs. On weekday mornings there was Romper Room, which my mother attempted to park my squirming sister in front of. I was a classic Goody Two Shoes and even I was repelled by Romper Room’s “Do Be a Do-Bee” kid propaganda. And I knew that at the end of each show when Miss Mary looked through her Magic Mirror, she would never see Gay and Lani, only Billy and Nancy and Susie.

The high point of my week was Saturday morning, the one time Lani and I could spend hours sprawled in all our glory and pajamas in front of the TV. The first thing to come on screen after the weirdly fascinating test pattern were wonderful old black and white cartoons, Merrie Melodies, Betty Boop, Popeye the Sailor Man, one after the other, with no interruptions from silly clowns or idiot children. Then came Mighty Mouse to save the day. The rest of the morning was not as idyllic, consisting of old half-hour shows thought suitable for kids: Roy Rogers, featuring Trigger and Dale Evans and for some reason Nellybelle the Jeep. The Lone Ranger and Zorro, both of whom were much handsomer and more dashing than stodgy Roy Rogers. Sky King, with his cute daughter, Penny, capturing various bad guys through aviation. And my favorites, the horse shows: Fury and My Friend Flicka.

I had a few plastic toy horses, inspired by the far better collection owned by my one and only friend, Judy Lindberg, who lived a few houses down from my grandparents in Carlton. Judy and I had become friends during my parent’s house-hunting days, when she was summoned to play with me. Round-faced Judy seemed almost as friendless as I was. I envied her world-class plastic horse collection, her thousands of Legos (My mother hated anything with lots of tiny pieces), and her status as an only child, a rare exotic when two kids seemed the minimum and lots of families had five or six. Judy’s very German grandfather, Karl, and her parents, Vera, with raven Elizabeth Taylor hair, and roly-poly Julius, owned Carlton’s one and only restaurant. The small café had a few booths along one side and on the other a long counter with those glorious chrome stools; Judy and I were strictly forbidden to do any spinning on them. On the counter and tables were the most adorable china cow creamers, as Minnesotans drank coffee with every meal. I broke one once, mesmerized by the stream of milk pouring out of the cow’s mouth, and I was scared for weeks to go to Judy’s house, terrified of what Germanic punishment might be meted out by her formidable grandpa Karl.

I got to play with Judy quite often, even after our move to Duluth; my family spent almost every Sunday in Carlton. While the adults sat around drinking and talking and drinking, I walked myself down the street to Judy’s, where we played horsies or Legos or fooled around with her mother’s electric organ, or I would sneak a look at Judy’s collection of fascinating, brightly-illustrated books that tried to explain Catholic theology at an 8-year-old level. Judy complained that reading wasn’t playing, and she was right.

***

If Judy wasn’t around on our Sunday trips to Carlton, I roamed about outside by myself, or explored my grandparent’s big house. On the ground floor there was a small wood-paneled room decorated with the heads of animals. My grandfather loved to hunt; in the winter he would drive around the county, dropping bales of hay off in the woods to make sure enough deer would survive so he could shoot them the following fall. There was an elegant living room that we never sat in; everyone congregated in the new glass-walled sunroom my grandparents had added on so they could look out at the snow eight months a year. My grandmother had remodeled her kitchen at the same time; her aqua blue and pale yellow kitchen was right out of Disney’s Tomorrowland and seemed the height of modern sophistication to me: the freezer made ice, there was a dishwasher, and the Formica counters were festooned with space age parabolas.

Upstairs were “the boys’ rooms” that had belonged to my dad and his two brothers. There the main attractions were the leather albums of coins and stamps from Rhodesia, Ceylon, French Guinea, and other exotic-sounding places I longed to visit even though those countries were just a colorful bit of paper or a coin with a hole stamped out; I could not have found them on a map.

Also upstairs was my grandma’s big bedroom, neat as a pin, reeking of Youth Dew, and too intimidating for me to do anything besides look at myself in her three-sided dresser mirror.

Best of all, my grandparents had a room just for books. It wasn’t big, but it was definitely a library, with towering bookcases on all sides holding hundreds of books in no particular order. There were tomes on dentistry, dusty fabric-covered novels with tiny type and no conversations, ancient nature books with pastel drawings of birds and moths—I just had to keep pulling books down from the shelves until I found something I could enjoy. When I did, I left that book on a lower shelf so I could find it again the following Sunday. There were two books I read again and again; a book on space travel, with lurid sci-fi paintings of the rings of Saturn as seen from the surface of that planet, and sunset on Mars with its two moons hanging in the sky; and a guide to hunting in Africa, bound in leopard-print paper and filled with black and white photos of living and just-shot gnus, zebras, lions, and a wide variety of antelope. If I ever go to Africa, I will carefully shake out my shoes every morning, having seen a photo of a large scorpion that had been extracted from the author’s boot. When I was in junior high, I discovered in my grandparents’ library an unaccountable paperback of Hell’s Angels by Hunter S. Thompson, with such horrifying descriptions of sex and violence, including bikers pulling a train on one poor girl, that I took special care in secreting it behind the encyclopedias so I could read it again and again. I have no idea who would have brought that book into that house.

My grandfather had a small bedroom tucked beneath the stairs, where he retreated immediately after Sunday dinner. I thought it was funny that my grandpa’s bedtime was 7:30 until I realized years later that this was his regular time to pass out from drinking 7&7’s all day. Every Sunday I scarfed down my own dinner as fast as possible to catch Lassie and the Walt Disney Show, which later became the even more unmissable Wonderful World of Color. My mother and grandmother cleaned up the dinner plates, my dad built himself a last highball, and then we piled back in the car, my dad drunk and all of us seat belt-less, to drive the half hour back home, where I had to go immediately to bed.

My grandfather’s brother was married to my grandmother’s sister, but while my grandpa was the big man and my grandma the snooty matron in their town of 400 souls, my great uncle Cliff and great aunt Marge were stuck on a farm with a thousand turkeys. Every Christmas Eve Cliff and Marge opened their rambling 1920’s house to dozens of relatives. Aunt Marge started baking in the beginning of December: there were cut-out sugar cookies shaped like stars, bells, and camels, dusted with red and green sugars; spritz cookies, ridged wreathes of pale green, decorated with those adorable little silver balls that you’re not suppose to eat, but that I could never resist crunching between my teeth; pfefferneuse, snowy with powdered sugar, that I always forgot I didn’t like until I had popped one in my mouth; chocolate drops, that I did like, tart lemon bars, homemade white bread to be slathered with butter, and stolen, studded with candied cherries and iced with white sugar frosting.

Marge made candy as well, a feat I have tried again and again to duplicate and consistently failed at: chocolate walnut fudge and penuche and divinity. These were the main attractions for me and it was torture to gaze upon the kitchen table groaning with sweets and not be able to have any until I choked down a plate of wild rice with mushrooms and chicken, baked ham, mashed potatoes, string bean casserole, and ambrosia salad. There were bowls of many other things, such as beets and lima beans, that I didn’t eat, and since it was Christmas, nobody made me. It was farmhouse cooking at its most gargantuan. I don’t think anyone even thought of bringing a dish to Aunt Marge’s Christmas Eve. It would have been like showing up at the miracle of the loaves and fishes with a Tupperware container of pasta salad. Our family did presents Christmas morning, after Santa came. Cliff and Marge did presents Christmas Eve, between bouts of eating. There was always one present for me, so I would have something to open; I tried not to look disappointed at the handmade monkey sock puppet or yoyo doll. Then there was that annus horribilius when my sister got a Raggedy Ann doll, something I had always wanted; I gleefully torn open my own gift to reveal the dreaded stitched grin of Raggedy Andy. I cried all the way home.

George Orwell’s 1984: A Review

We share a review of George Orwell’s 1984 from The September 1, 1972, issue of the Post, 23 years after the initial publication of the book. The reviewer notes, “The realization has been gradually growing that Orwell possessed completely remarkable insights and foresights, that he saw something then that the rest of us are only beginning to see now.”

Sales of the influential book have spiked in the last four months, as people once again find Orwell’s writing to have resonance in today’s political climate.

***

When it appeared in 1949. Orwell’s ominously titled 1984 doubtless seemed to many to be at most an absurd parody of the Russian communist state, so overdrawn and so farfetched that it offered little to the reader.

But each successive year since its initial publication has brought revised appraisal, a growing anxiety on the part of past and new readers alike that it was just possible that they were missing the message. The realization has been gradually growing that Orwell possessed completely remarkable insights and foresights, that he saw something then that the rest of us are only beginning to see now.

Orwell was born in Bengal at the beginning of this century, completed his formal education at Eton, became a thoroughgoing Socialist who fought with the Loyalists during the Spanish Civil War. He was to die at forty-six, but not before he had clearly, if frighteningly, depicted the fate of mankind if the direction of political and social forces were not reversed.

In the present edition Erich Fromm has written a short but illuminating “Afterword” that ought to be read before tackling 1984 itself.

Reviewing earlier Utopias, such as the work of Thomas More which gave us the name, Fromm correctly identifies them as expressions of the perfectibility of man, as the basis for a happy optimism about man’s future.

Against these he contrasts the “negative utopias” of which 1984 is perhaps the most notable. Writing of them, he even anticipates the title that Skinner was to choose ten years later: “The question is a philosophical, anthropological and psychological one, and perhaps also a religious one. It is, can human nature be changed in such a way that man will forget his longing for freedom, for dignity, for integrity, for love—that is to say, can man forget he is human’!”

Winston Smith is the man about whom Orwell’s book revolves, London is the scene of the action, and all through the narrative words and expressions evolve which have worked their way into our own everyday vocabularies.

Winston’s flat, like everyone’s, is under the eternal surveillance of a telescreen through which, as posters everywhere proclaim. BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU. Not too far away was the Ministry of Truth, said to contain three thousand rooms, which carried on its side these distillations of party wisdom:

War Is Peace

Freedom Is Slavery

Ignorance Is Strength

There was “the Ministry of Peace, which concerned itself with war; the Ministry of Love, which maintained law and order; and the Ministry of Plenty, which was responsible for economic affairs. Their names, in Newspeak: Minitrue, Minipax, Miniluv and Miniplenty.”

We witness a forbidden love that began and briefly flourished under the unseen eyes of the Thought Police, a love that subsequent torture led both participants to betray and denounce the other.

We see history recorded, history erased, so that nothing is known of yesterday, so that even the today that we think we see is wholly the contrivance of Big Brother.

We observe O’Brien from the Thought Police, presiding over the degradation and reconstitution of Winston, by means of drugs, electric shock treatments, starvation, beating. We hear him summarize the new world the party was forging.

“In our world there will be no emotions except fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement. . . . We have cut the links between child and parent, between man and man, and between man and woman. No one dares trust a wife or child or a friend any longer. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stomping on a human face—forever.”

Fromm ends his “Afterword” with the admonition that “Books like Orwell’s are powerful warnings and it would be most unfortunate if the reader smugly interpreted 1984 as another description of Stalinist barbarism, and if he does not see that it means us, too.”

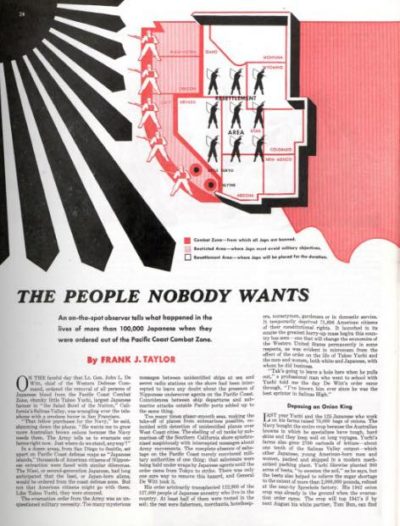

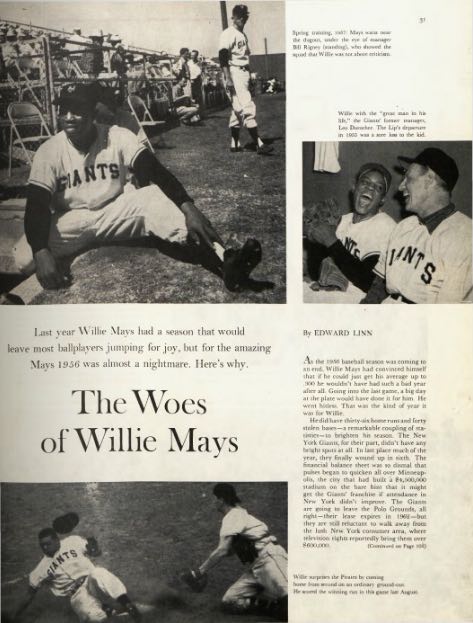

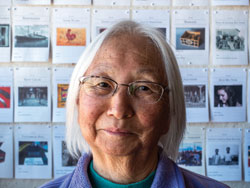

The People Nobody Wants: The Plight of Japanese-Americans in 1942

Originally published May 9, 1942

On the fateful day that Lt. Gen. John L. De Witt, chief of the Western Defense Command, ordered the removal of all persons of Japanese blood from the Pacific Coast Combat Zone, chunky little Takeo Yuchi, largest Japanese farmer in “the Salad Bowl of the Nation,” California’s Salinas Valley, was wrangling over the telephone with a produce buyer in San Francisco.

“That fellow purchases for the Navy,” he said, slamming down the phone. “He wants me to grow more Australian brown onions because the Navy needs them. The Army tells us to evacuate our farms right now. Just where do we stand, anyway?”

In a dozen areas, from San Diego to Seattle, set apart on Pacific Coast defense maps as “Japanese islands,” thousands of American citizens of Nipponese extraction were faced with similar dilemmas. The Nisei, or second-generation Japanese, had long anticipated that the Issei, or Japan-born aliens, would be ordered from the coast defense zone. But not that American citizens might go with them. Like Takeo Yuchi, they were stunned.

At least half of the 112,905 people of Japanese ancestry affected by the order were rooted in the soil; the rest were fishermen, merchants, hotelkeepers, nurserymen, gardeners, or in domestic service. It temporarily deprived 71,896 American citizens of their constitutional rights. It launched in its course the greatest hurry-up mass hegira this country has seen.

“Tak’s going to leave a hole here when he pulls out,” a professional man who went to school with Yuchi told me the day De Witt’s order came through. “I’ve known him ever since he was the best sprinter in Salinas High.”

Yuchi’s own family, consisting of his alien mother, his Salinas-born wife, his 8-year-old daughter, 6-year-old son, and a baby daughter, is an average California-Japanese household. His wife’s brother, Hideo Abe, is in the Army. His younger brother, Masao, was called in by the local draft board for his physical examination the day I was there. Of the 21,000 Japanese families on the Pacific Coast, one in every five has contributed a son to the Army.

“Well, are you going to go voluntarily or wait until the Army evacuates you?” I asked.

“It’s a tough one to figure out,” Yuchi replied. “I’m American. I speak English better than I do Japanese. I think in English, not Japanese.”

After leaving the Yuchi household, I called on another Nisei, Dr. Harry Y. Kita, a dentist. Prior to Pearl Harbor, Kita, a University of California graduate, enjoyed a thriving practice. Half of the patients who sat in his three chairs were whites. Since then, most of them had been from the Japanese community. “I haven’t much practice left,” said Kita, with a hearty but forced laugh. “I understand why it is,” he continued. “I feel American. I think American. I talk American. My only connection with Japan is that I look Japanese.”

“Could you tell a good Japanese from a bad one?” I asked him.

“No more than you could,” he replied. “But if I knew one who was disloyal to this country, you can bet I’d turn him in.”

Dorothea Lange

Vegetable Wars

From white vegetable growers I heard the other side of the story. The Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association had just published a brochure titled NO JAPS NEEDED to counteract a widespread impression that Californians would go hungry if the Japanese truck gardeners were removed. The dislike of the militant Grower-Shipper Association for the valley’s Japanese farmers is an old and bitter one. The association is composed of a few score large-scale white growers who lease lands, produce lettuce, carrots, and other fresh vegetables the year round in the Salinas, Imperial, and Salt River Valleys for the Eastern markets. … At one time the lettuce growers, like the sugar-beet growers, depended upon Japanese for field labor. As the Japanese, one by one, became farmers in their own right, and competitors, their places in the field were taken by Mexican or Filipino labor. White men and women, largely Oklahomans, handled the trimming, icing, and crating in the packing plants, but they were never able to endure the back-breaking stoop work in the fields. Only the short-legged Japs could take that.

Shortly after December 7, the association dispatched its managing secretary, Austin E. Anson, to Washington to urge the federal authorities to remove all Japanese from the area. “We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons,” Anson told me. “We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, and they stayed to take over. … If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we’d never miss them in two weeks, because the white farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we don’t want them back when the war ends, either.”

The Japanese-American loyalty creed, to which all Nisei publicly subscribe, is about to get its first real test, particularly these portions of it: “… I am firm in my belief that American sportsmanship and attitude of fair play will judge citizenship and patriotism on the basis of action and achievement, and not on the basis of physical characteristics. … Although some individuals may discriminate against me, I shall never become bitter or lose faith, for I know that such persons are not representative of the majority of the American people. …” In such a test, the tolerance of the new host states will also feel the fire which has been ignited by the obvious requirements of a stern military emergency.

—“The People Nobody Wants,” Frank J. Taylor,

May 9, 1942

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Also read Unwanted: A Teenage Memoir of Japanese Internment from the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

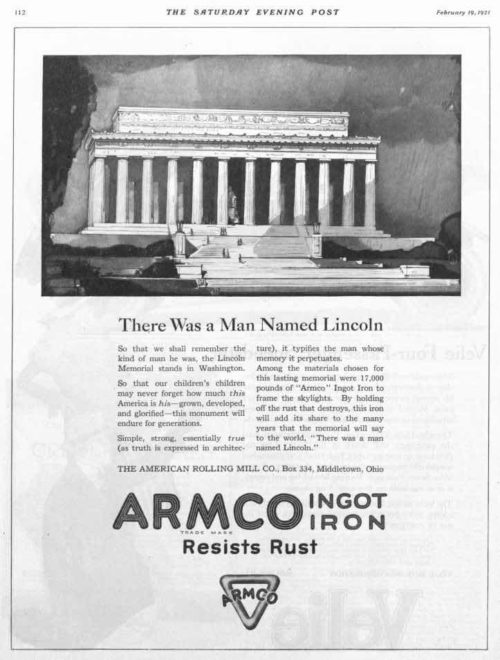

Vintage Advertising: The Lincoln Memorial

After decades of planning, budgeting, and construction, the Lincoln Memorial was finally dedicated on May 30, 1922. Americans were proud of this beautiful monument and eager to visit it. Companies wasted no time using the memorial to advertise a connection to their products. These advertisements appeared in the Post between 1921 and 1948 and hawked everything from tires to tombstones.

The Lincoln Memorial has taken on additional layers of meaning since the 1920s. As Jay Sacher noted, “the memorial is cultural shorthand for both American ideals and 1960s radicalism.” It is rarely seen in ads anymore. The memorial still makes regular film appearances, an easy stand-in for Heavy Symbolism. However it is used, the Lincoln Memorial will continue to transcend the banal appropriations of its image.

February 19, 1921

Click to Enlarge

Armco iron was used in the construction of the Lincoln Memorial, a fact that warranted several full-page ads in the Post.

October 28, 1922

Click to Enlarge

We’re not sure what the Lincoln Memorial had to do with a company that made ledger sheets and looseleaf binders, but they seemed to hope that the monument would lend them an air of dignity. The Lincoln Memorial certainly didn’t represent “cutting office costs,” as its construction costs in today’s dollars were north of $40 million.

December 1, 1923

Click to Enlarge

Marmon made cars in Indianapolis from 1902-1933. The Lincoln Memorial serves as the majestic backdrop to emphasize “the ultimate in luxurious transportation.”

March 14, 1925

Click to Enlarge

Many Americans wanted to visit this new monument, but how were they to get there? The Baltimore & Ohio Line, of course – the “only route New York, Chicago and St. Louis, passing directly through Washington, where liberal stop-over privilege is accorded.” (No such privileges for the conservatives?)

February 25, 1928

Click to Enlarge

Of course, if you’d rather drive than take the train, you’ll need a good set of tires to get you there.

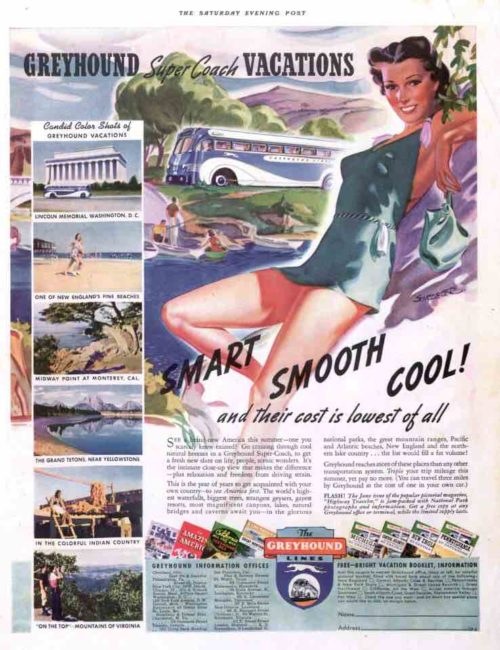

June 4, 1938

Click to Enlarge

The Lincoln Memorial takes a backseat to this green-suited come-hither swimmer in an age where sex was starting to trump integrity as a selling point.

May 4, 1940

Click to Enlarge

The Lincoln Memorial once again gets low billing. In case you can’t read the caption, it says, “Newlyweds Betty and Bob Graves from Connecticut gaze at themselves and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington’s famous Reflecting Pool. What Betty really sees is a picture of herself getting delicious, economical breakfasts for Bob in her own little house with her new glass coffee pot and the heavenly new Chase & Sanborn Dated Drip Grind Coffee in the money saving package!” Our research was unable to confirm if that’s what Betty was actually seeing.

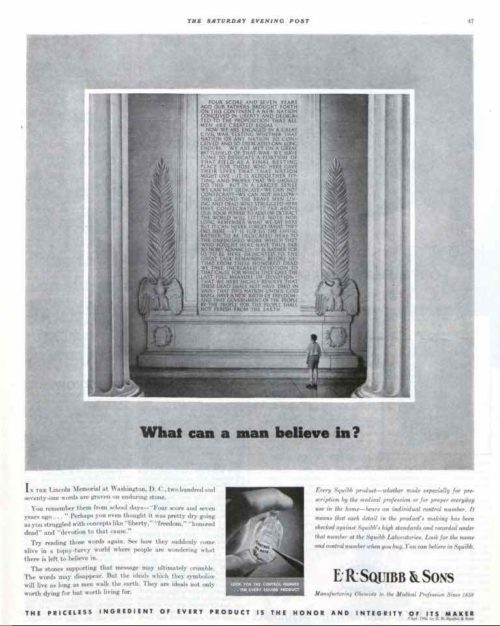

January 11, 1941

Click to Enlarge

Pharmaceutical manufacturer Squibb offers inspiring words – “The stones supporting that message may ultimately crumble. The words may disappear. But the ideas which they symbolize will live as long as men walk the earth.” (Buy our drugs.)

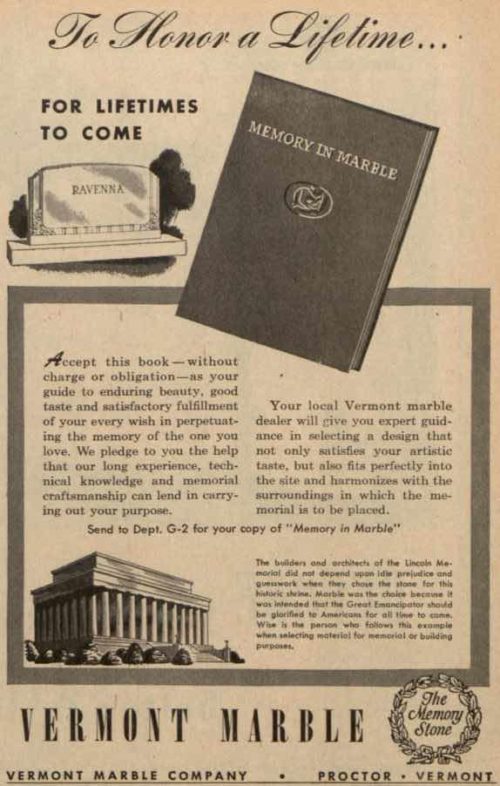

May 1, 1948

Click to Enlarge

The argument is that the Lincoln Memorial is made out of marble, so your tombstone should be, too. “Wise is the person who follows this example when selecting material for memorial or building purposes.”

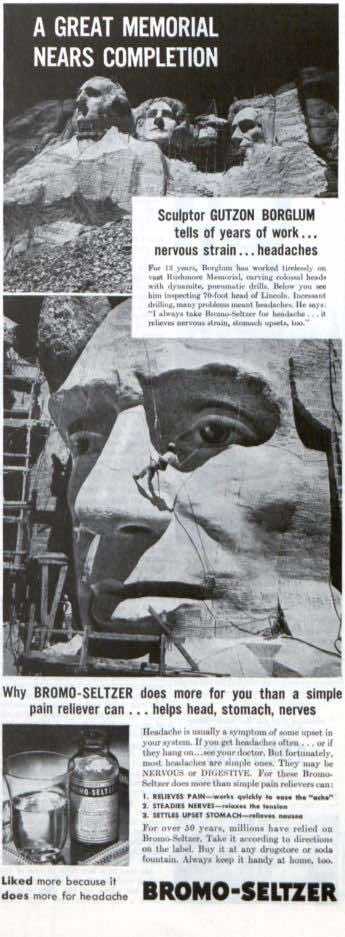

August 31, 1940

Click to Enlarge

We threw in this ad just to show that the Lincoln Memorial wasn’t the only monument used in the service of advertisers. The sculptor of Mt. Rushmore ostensibly took Bromo-Seltzer for his headaches. Early versions of this medicine contained sodium bromide, a tranquilizer. That may not have been such a good idea when he was dangling off the side of Lincoln’s nose.

“Comrades in Arms” by Josephine Daskam Bacon

This is the story of a spoiled girl who hadn’t the least idea that her parents had spoiled her. Nor, for that matter, had her parents any such idea — far from it. They would have told you that the amounts of money, time and worry they had spent on the child were beyond belief. She had been brought up—for some inscrutable reason known only to her sort of parents — to speak French before she could speak English; she played the piano rather well, the violin rather badly; she danced beautifully.

German she began at twelve, Italian at sixteen, when they took her to Florence; at one time she joined a Spanish class, but shifted to barefoot dancing later, and after that to hand-wrought jewelry.

“Miss Griswold,” her dancing teacher said of her, “is a great puzzle to me. She ought to be so much more of a success than she is. She really dances extremely well, but somehow she never looks the part!”

And that was true; when you watched Elizabeth swaying through a Spanish dance you decided that her regular features were really rather cold and classical; but when she lifted her left foot, in that attitude of one who has unwarily stepped on a toad, so common to the Greek friezes, and paused, listening, you realized that her eyes were too brown — or something. When her hair fell loose, it was too straight; when, on the other hand, it had just been waved by the trusty Marcel method, it looked too artificial.

Was it self-consciousness — too much New England blood with not enough New England convictions? Her mother never knew.

She had been born in New York and, except for the Maine coast and Florida, knew little else of her country till her twenty-fourth year, when their family physician in despair had suggested the air of the Rockies; and Elizabeth, conscientiously attired in riding breeches and sombrero—she would have worn “chaps” if necessary — rode a vulgar little cow-punching bronco across the plains for six weeks. It seemed to do her good, they thought; but still she was listless, and though perfectly willing to go back to the ranch, if they liked, she was equally willing to stay in New York and take up something else. She had been out in society for five seasons, and no man or boy had proposed marriage to her.

Now, why was this? She was not in the least bad-looking; distinguished, rather, in a regular New Englandish way, with a clear profile, clever, thoughtful eyes and a sufficiently mobile mouth. She was pale, it is true, but are not most American girls rather pale than otherwise? She was a little too thin perhaps, but these are thin years, and many a luscious little fat girl envied Elizabeth her hipless, slim-ankled silhouette. She had been super-educated possibly; but on the other hand she had been sedulously taught to conceal this, and could talk as many banalities to the minute as any of her friends. She sat behind her mother’s tea urn, charmingly dressed, and listened as interestedly as possible to the account of your surgical operation, your Pekingese or your baby—giving you, meantime, just the dash of cream or slice of lemon you had asked for. She wasn’t prickly or catty or piggish about men or rude to her elders; nor was she a prig. And yet—and yet —

As a matter of fact, I believe her to have been the chief sorrow of her mother’s life. Mr. Griswold would have been surprised indeed to hear me say so, for he had paid for all the subjects Elizabeth took up, and was very proud of her. Sometimes he may have wondered just why she should have to take up so many, and what she found to enjoy in them; but he paid for them, just as he had paid for her expensive coming-out party and her riding boots and her teeth-straightening and her lectures on gardens and wild birds.

He didn’t even complain when Mrs. Griswold decided that Elizabeth ought to have a studio.

“B-but can she paint?” he called, round-eyed, through his dressing-room door, struggling with his third white tie.

“Of course not, Ben; she doesn’t pretend to.”

“Going to learn?”

“Oh, no — it’s not that, exactly, dear. A good many of the girls have them now, and I thought it might make her feel freer, perhaps less tied down.”

“If Beth had been born an orphan she might have amounted to something,” one of her friends once grumbled. But she was not an orphan; she was hopelessly a daughter.

“It’s the darnedest thing about Beth Griswold,” I heard one of the girls of her year murmuring one day when we were both sitting on a float fifty yards from the pier, with our feet hanging comfortably in the water.

“Huh?” the other girl inquired elegantly, stuffing sodamint tablets—for which she had a passion — into her moist little red mouth. Neither noticed me, for I was over thirty.

“Huh?” the other girl inquired elegantly, stuffing sodamint tablets—for which she had a passion — into her moist little red mouth. Neither noticed me, for I was over thirty.

“It sure is,” pursued the first thoughtfully, wriggling her toes in intricate patterns.

“She’s a peach of a swimmer, but nobody cares a whoop somehow.”

“Oh, yes, she can swim all right, all right — but she doesn’t get ‘em, does she?” agreed the second, through an ecstatic mouthful of soda mints.

“No pep!” concluded the first succinctly. “Dead man’s float — let’s?”

And they fell off the rocking platform simultaneously, assuming ghastly attitudes. They were high-stand graduates from one of our leading educational institutions for young ladies, and I supposed them to be recuperating their minds from the strain of a too strictly censored vocabulary, and gathered that they deplored in their friend a degree of personal magnetism and vitality incommensurate with her undoubted aquatic accomplishments.

That was the August of 1914, and all over the astonishing little country of Belgium blood was running.

Mr. Griswold was worried, and passed, as the months rolled by, from worry to horror, and from horror to alarm. At last he began to write letters to the Times, and read them to men at the club. Mrs. Griswold promptly became enmeshed in a web of committees — when she wasn’t serving on one she was forming another, and rarely lunched at home. Cortwright Griswold, their only son, hammered furiously at his parents for permission to drive an ambulance in France; Katy, Mrs. Griswold’s maid, who had buttoned and hooked Elizabeth since the day when she blossomed from safety pins into buttons and hooks, drew out all her savings and began sending them to Ireland; Georges, the chauffeur, got his papers suddenly and departed to join his regiment somewhere in the Valley of the Marne.

More months rolled by, and shoes became sickeningly costly; and suddenly even satin slippers, which they couldn’t very well be wearing in the trenches, one would suppose, took on a value that forced one to consider one’s allowance rather carefully.

“Disgusting! Simply disgusting!” said Mr. Griswold irritably. “I can tell you, my dear, the day for pearl-gray satin slippers at seventeen dollars a pair is rapidly passing!”

“I know, Ben; I know,” Mrs. Griswold replied pacifically; “it’s dreadful. But what is the child to wear? She can’t very well dance in tan boots. And all these dances are for hospitals or Belgian babies or things like that.”

Mr. Griswold explained, briefly but plainly, his feeling for such dances.

“I know, Ben, but people won’t give money without something like that. That orphan-baby dance last week made thirteen hundred dollars.”

“Oh, well — ”

And more months rolled by.

Suddenly Cortwright was at Plattsburgh, and Mrs. Griswold was delighted, and her husband grew silent and absorbed, and stayed longer at the office. Everybody began to stand up jerkily when The Star-Spangled Banner asked them, Oh, say, could they see, at restaurants and theaters. And quite the nicest people went to the movies to follow the war films. Elizabeth got very tired of watching the Czar climb down the trenches.

Indeed, she found herself very tired, somehow, just as all her friends were growing so busy and so busy and so busy. She took the Red Cross nursing course, naturally, and one in first aid, but the Red Cross teacher, a brisk, flat-chested woman with a strong Western accent, advised her very frankly against going into any but the most elemental mysteries of her fashionable science.

“You see, my dear Miss Griswold, it’s so much a matter of pursonal’ty,” she said, “nursing is; and reelly, I must say I don’t think you’ve got the right pursonal’ty for it — if you get my idear.”

The class in first aid was even more unfortunate. It went on in the parish house of a fashionable church, and a nice old family doctor, who had brought many of the young ladies into the world, gave them the lectures. Somebody was to provide a choir boy to be bandaged, but he was an elusive choir boy and missed most of the mornings, and a few of the cleverest girls got all the practice in resuscitation and splints by using the obliging members of the class as victims. Afterward a very severe young surgeon with a pronounced German accent burst in unexpectedly and examined them—two questions apiece. He wore his stiff black hair en brosse, which is always so disconcerting, and whatever he asked you, the answer turned out to have been “cracked ice”; which the nice old doctor had hardly mentioned.

Elizabeth’s questions were convulsions in infants and sudden bleeding from the stomach; in the first case she forgot the cracked ice, and in the second she failed to see how it could be usefully applied, unless the patient could be induced to eat it, and as she presupposed him to be unconscious at the time, she didn’t suggest it. When they turned up at the parish house the next week to get their diplomas, they were met by a typewritten slip, sandwiched between the choir rehearsal and the Ladies’ Auxiliary, which informed them that none of the class had passed!

Elizabeth didn’t care very much; it had been her mother’s idea. She went languidly to a set of talks on the Balkan Situation, where everybody knitted; and later joined a committee for collecting old linen for a big, new surgical-dressings committee. But the district given her was away up on the West Side, and as she couldn’t take the motor on those days and wasn’t allowed to use the subway, she stood so long on the corner in the rain waiting for the bus that she caught a heavy cold, which ran into tonsillitis — it was, you will remember, a tonsillitis year — and by the time she could get out again her place on the committee had been filled by an energetic girl with an electric runabout of her own.

The months rolled by and there was getting to be quite a little list of Americans who had been killed, in one way or another, on account of this horrible European war, and many of her friends wore little button knots of Allied ribbon. Mrs. Griswold was forced in the interests of digestion to ask guests not to mention the President if they could help it, it made Ben so angry; and Cortwright, who became 21 on a Tuesday, ran away to France with one of his cousins on the Thursday following, and drove his new birthday car through the second war zone, filled with hospital supplies. Mr. Griswold scolded him soundly by letter and boasted of him at the club, and his mother turned his bedroom and study into a shipping depot for tobacco for the trenches and old clothes for various devastated regions.

Mr. Griswold became chairman of one of the relief committees at the club and secretary and treasurer of a Harvard Alumni committee, and went to a great many men’s dinners. As Mrs. Griswold rarely came home to luncheon now, and the cook’s son had recently joined the National Guard, which for some reason preyed on his mother’s mind to such an extent that she confined herself to what she called some little thing on a tray for Miss Elizabeth, the girl, who had never been much interested in her food, began to grow really thin and you noticed her cheek bones.

I mentioned this, incidentally, to Mrs. Griswold, who became extremely vexed and left me with the impression that Elizabeth was very unpatriotic to have grown so thin, and I nearly as much so to have remarked it. A bottle of port-and-iron was placed on the sideboard, out of which the girl very sensibly poured a little over the roots of the table ferns now and then. I call her action sensible because iron disagreed with her digestion — feeling, indeed, like a sharp three-cornered stone in her chest—and the port went to her head.

The months rolled on, and now a strange thing occurred: utterly aside from Europe, and the President, and the ridiculous state of the Army, and the probable effect of German propaganda on the Irish, something happened to Elizabeth herself! Something, actually, which her mother had not planned and her father had not paid for — something she stumbled into all alone!

It happened in this way:

She was in the habit of going to her Cousin Lou’s once a week or so, to play with the children when their mademoiselle went for her weekly afternoon out, an afternoon devoted nowadays to packing great bales of comforts for the American Fund for the French wounded. There had always been a Fraulein until now, but when all the Frauleins turned out to be without doubt German spies—;they spent their time in giving important Germans maps of their employers’ houses—Cousin Lou turned away hers, weeping—she had been the most marvelous packer, my dear, and knitted the most beautiful sweaters, and the baby cried for a week! —and engaged Mlle. Dupuy, who slapped the children, one feared, and had headaches; but then, think what France did for us when we were fighting for our freedom!

Elizabeth was really fond of children and got on well with them. She sang them funny little French songs that her old bonne had been used to sing to her: Maman, les Oils bateaux qui s’en vont and Il pleut, it pleut, bergere; she tied bandages on their wounded soldier dolls; she even had tea with them occasionally.

One afternoon Lou was having a meeting at her house, and mademoiselle had agreed to stay with the children, as it was raining. Elizabeth, who had come as usual, strayed into the meeting, at her cousin’s earnest request, and listened politely to the speaker, an eager, dynamic little creature —nobody in particular, really — with a solid genius for organization and inspiration. She had been a trained nurse, it appeared, had married a doctor, and lived in an apartment on Gramercy Park. She had raised thousands of dollars for the orphaned children of France, and did mighty fieldwork as a missionary for that cause. Indeed, she threw out, in passing, the desire of her heart was to dedicate herself entirely to that work and direct it from the city headquarters all day long, but that she could not feel justified in leaving her three children, the oldest not yet seven, to the care of servants.

“Think, only think!” she cried, throwing out her arms with an impassioned little gesture, “think what I could do for this wonderful work of ours if only some one of the hundreds of nice women in New York who are of no earthly use to anybody would come and take care of my children! I don’t say wash them and blow their noses for them and tidy their rooms — I can afford a good nurse for that. But my husband doesn’t approve of schools for children until they are eight years old, and I’ve always been with them a great deal; I don’t want to leave them with servants. Somebody ought to organize all the women who haven’t any special gift and release those of us who have! They ought not to expect any pay” — her smile was half whimsical, half fanatic —“they ought to feel that they’re just doing their bit. Don’t you agree with me, ladies?”

They laughed and applauded enthusiastically; her ardor was contagious. “Heavens! I wish she could reorganize the office for us!” murmured the woman whose name headed the engraved letter paper of the great charity; “she’s a little wonder!”

Then they moved and seconded for a few minutes and went on to the next thing — all, that is, but Elizabeth. She sat staring at the little speaker, and later followed her quietly into a Madison Avenue street car.

“I am Elizabeth Griswold,” she explained, “and I wondered if you would be willing to let me take care of your children while you were at headquarters? I could come every day if you liked. Lou Delanoy is my cousin.”

“I think that’s perfectly fine of you, Miss Griswold,” cried the little wonder delightedly. “I should like to be at headquarters from nine till five, except Saturdays, this month anyway. Things are in an awful mess down there. I’ll have Dagmar bring the children right down to the park to you on fine days, and then she can address circulars for me and attend to the telephone. I knew there must be hundreds of girls who would like to help me out, but I didn’t expect to find one so soon. And you realize, don’t you, that you’ll be doing every bit as much in your way as I shall be in mine?”

Elizabeth smiled vaguely.

Elizabeth smiled vaguely.

“I wanted to do something,” she said. “Shall I come tomorrow?”

Her next step I am almost ashamed to tell you, if you happen to be a sensible, practical person: She went to a most expensive specialty shop on the expensive avenue and asked for nurses’ uniforms. Blue ones she purchased, with bib aprons and little caps that stood up in the front; and when the attendant asked “Will you like to look at the capes and bonnets, miss?” she nodded seriously.

“They’re thirty dollars — but of course the war — ” murmured the attendant; and Elizabeth, to whom it had never occurred that a coat could be purchased for thirty dollars, said gravely “Of course.”

“The nurse will be about your size, miss?”

“Yes—about my size,” said Elizabeth.

Now of course you and I would never have been so foolish. We know that one can sit in Gramercy Park and superintend the play of three children in whatever dress she happens to have on at the time — a bathing suit, as far as that goes, were it not for the park regulations. But Elizabeth, you must remember, was only 24, and had, like most people, her own particular little romantic tendencies. They may not have been yours or mine, but they were hers; and, besides, all her friends were fussing about some kind of uniform or other — this was her uniform.

She never, in her wildest dreams, could have imagined what that uniform was to do for her!

At eight the next morning she stood by her mother’s breakfast tray.

“I’m doing some work for the Relief Reorganization Committee,” she announced briefly; “I’ll be busy all day, probably.”

“That’s good,” Mrs. Griswold replied, her eyes on her mail; “there’s nothing like an interest — Oh, what a fool that stenographer is! I shall simply have to have a special one for my department, that’s all. Remember, dear, we’re dining at seven tonight—your father had to take a box for that Serbian Relief concert. I asked Doctor Henderson.”

Elizabeth left the room in silence, with her lips pressed together. She understood perfectly well about Doctor Henderson. He was forty and distinctly baldish and a little tiresome. Adenoids were — or was — his specialty, and he danced painstakingly, with a tendency to perspiration and counting the time under his breath. Nobody had ever suggested that since she was nearly 25 and since he was the only unmarried man — at least he was a widower — who had ever shown the least interest in her, and since he was doing very well indeed and would undoubtedly do much better, why, he was a very desirable extra man to sit in the box or go on to a dance later. Nobody, I say, had ever so slightly suggested it, but Elizabeth understood very well. She was serious; Doctor Henderson was serious. The inference was obvious.

Of course it all seems very queer to me, if you ask me. Why a young person should be brought up like a duchess in order to marry a surgeon at the last, I can’t see. He was making, we’ll say, 20,000 a year; maybe a bit less, maybe a bit more. But we all know what rents are in New York, and a doctor must have a decent house in a decent part of the town if he wants to cut out rich children’s adenoids. And Elizabeth didn’t know whether chops grew in the sheep’s cheeks or in its legs. And I told you what her evening slippers cost. She had no idea what wages parlor maids get nowadays or what coal costs a ton. Somebody had always turned on her bath for her, and one day when her little satin bed shoes had not been placed by the side of her bed, she had been obliged to sit on her toes and call to her mother to ring for Katy to ask where they were! It is not that she was lazy at all, I assure you, but it never occurred to her that it was a part of her duty to hunt for her bed slippers.

In other words, she had been excellently brought up to marry one of the great fortunes of America; or perhaps it is only fair to add that she would have been useful to a brilliant young attaché to an important foreign embassy — but even he would have had to be reasonably well off, don’t you see?

The three little Gramercy Park children didn’t worry over all this, however. They were nice children and they took to Elizabeth promptly.

This isn’t a bit like the old novels, you see; there is no suffering governess involved, patiently bearing with the rudenesses and cruelties of the brutal and the rich. No; it is really true that children brought up by their mothers are infinitely nicer and more interesting than children brought up by servants. The names of these children were Marjory and Barbara and Kenneth, and they were as pleasant as their names. Marjory rolled a hoop, Barbara pretended to be an Indian, and Kenneth sat in a sort of infantile bath chair and talked to the birds, having but slight command of ordinary English. Elizabeth sat on a bench and impersonated, alternately, a buffalo and a white captive, neither of which roles was at all difficult. Her hands were in her lap and she gazed at the spring sky and the feathery trees. She was particularly contented and was enjoying a new sensation; she was looking prettier than ever before in her life, and she knew it!

For that strange thing, artistic setting, had transformed her, and though it might take an artist to have analyzed this, it didn’t require an artist to realize it, you see. Elizabeth had always been dressed by her mother, who had never been able to resist managing everything and everybody round her, and she had never observed that what had suited her in her youth didn’t suit her daughter today. If she had seen this daughter on her bench in Gramercy Park it would have dawned on her that she should have been sent to fancy-dress balls as Priscilla, the Puritan maiden, and not as a Persian princess. The prim little white collar, like a clergyman’s, the clean blue and white of the uniform — above all, the flat little English bonnet, which was nothing but a smooth bow spread over her smooth hair, framing her smooth forehead — all made her type jump out to you. The girl was charming.

Her hair came down in a sharp widow’s peak straight between her level brows; her eyes looked large and interesting. As an efficient New York beauty one wouldn’t have considered her, of course, but as a nurse in a park she was strongly arresting. She showed every inch of her breeding, every ounce of her education, every minute of the repressions of civilization that had fixed her type and personality. I tell you, she looked like the nurses Mr. Gibson and Mr. Christy draw on magazine covers; and you know as well as I do that men cut these out and frame them. Anyone would have turned to look at her.

It is very ironic that Mrs. Griswold could not know this, isn’t it?

At half past twelve they all went in to luncheon, and Elizabeth ate a chop and a baked potato and a large helping of string beans and two pieces of raisin bread, besides a dish of rice pudding with currant jelly and meringue on the top. While they took an hour’s nap she lay on a comfortable sofa and read a silly story in a magazine. There seemed to be no books of any particular cultural value about, and the doctor had to have plenty of magazines for his patients, for it is well known that you cannot be a doctor without magazines.

There was no tension in the house — nothing to live up to; that had all been transferred to headquarters. Elizabeth, though she did not know it, relaxed for very nearly the first time in her life. For culture, you understand, is quite as wearing as wage-earning If you go at it as seriously.

By quarter of three they were in the jolly, fenced-in little park again, and other children were playing with them. Barbara was a mermaid this time, and Miss Gizzle, as they called her, a shipwrecked mariner. Later she played a harp on her bench, while Barbara wallowed in the surf at her feet, to the great amusement of the young policeman who tramped round the park.

Dagmar called for them at five, and Elizabeth, her cheek moist from three sincere kisses, walked up Lexington Avenue to her studio, now a really useful room, changed her dress with all the thrill of a heroine in a melodrama, and hurried home.

“That’s a pretty frock, dear,” said Mr. Griswold at dinner; “pink becomes you.”

“I’ve worn it every night this week, papa,” she said, surprised.

The doctor examined the dress attentively, but he was not given to personalities.

The first day of the next week a slight accident occurred: Dagmar lost her park key. As you probably know, only the favored inhabitants of the borders of this park may enter it, and they have, each family, a key. Dagmar, much flustered, because she had heavy telephone duty that day, could offer no better suggestion than that someone should consult the policeman, who might know what to do; there was not a soul inside the iron fence, for it threatened rain, and they were very early.

“Very well,” said Elizabeth, and with her charges hanging to her skirts she went to meet the uniform that meant knowledge and protection.

“Have you a key to the park, officer?” she asked as he hastened his step a little to join her.

She did not notice the quick interest in his eyes; she was not in the habit of noticing policemen’s eyes. Are you?

She did not know, naturally, that her method of addressing this representative of the law was not at all the method of nursemaids in general. To her he was a servant of the city, paid to direct her to places she didn’t know, to clear the streets for her to cross, to keep from her eyes and ears things objectionable.

To him, as he looked down from his young tallness at the widow’s peak on her smooth forehead and listened to her clear, low voice, each word so perfectly cut from the others, she was simply the loveliest thing he had ever seen or heard.

“A key — into the park?” he repeated vaguely.

“Yes, yes — surely you or somebody must have one. We belong here,” she added hastily, “only our key is lost.”

“Oh, I’ve seen you here,” he said; “that’s all right. But — I don’t know — ”

He blushed violently through his freckled face up to his curly, sandy hair. He was fearfully embarrassed. Elizabeth, of course, could not know, but this was the first time he had ever been asked for the key, and he simply couldn’t remember, for the life of him, whether he ought to have one or not! He was clearly very much upset and she felt amused and sorry for him at the same time. Barbara pranced eagerly at her side.

“Let’s get in the first, Gizzle, the very first,” she begged.

“Look here,” he said abruptly; “I might just as well tell you as let you find out — I’m not very strong on this key business. I’m new here, you see, and if they told me about it I must have forgotten. Excuse me — I’ll look in my book.”

She waited, smiling, disarmed by this frankness, while he drew a little book out of his pocket and consulted it.

“It gets me,” he admitted at length; “I’ll have to call up and find out. I’m sorry — ”

“Oh, it doesn’t matter,” she said; “some of the nurses will soon come along and they can let us in. It was our fault, really.”

“But I’m supposed to help you out,” he insisted ruefully. “It doesn’t look as if I was much good, does it?”

He was quite young and so shy, evidently, that Elizabeth couldn’t resist laughing. Barbara laughed with her, and in a moment he was laughing too; and they all laughed together.

“You’re good-natured, anyway,” he said. For a moment she stiffened and stared slightly, then, with a sudden recollection, began to laugh again. Why shouldn’t a policeman be friendly with a nurse? This was part of the game. “Oh, well, why not be?” she answered; “it’s a lovely morning!”

“You’re right, it is!”

But he was looking at her and not at the morning; and she knew it.

Her spirits mounted; this was the nearest to an adventure that she had ever been in all her life. What would he have thought if he knew?

Dagmar was waving furiously; encumbered with Kenneth, she could neither leave him nor fly to the house.

“The other nurse wants to tell you something, doesn’t she?” he asked. “Shall I go and see?”

“Oh, no, I’ll go — just stay here with the children!” she cried, and flew across to the beckoning figure. Suppose Dagmar should call her Miss Griswold. That would spoil it all.

Dagmar had just remembered; the key was on the umbrella stand. Seizing the go-cart, Elizabeth piloted it halfway across the street, but only halfway, because the young officer ran to her aid.

“Let me take it,” he said, and pushed it carefully over.

They stood by the gate, waiting.

“They’re nice kiddies, aren’t they?” he muttered, still shy, but unwilling to yield to his shyness and go. “I like ‘em that age.”

“Yes; they’re very nice,” she replied, amused.

“I’ve noticed you before,” he volunteered; “you seemed kind to them. Some of the nurses — well, you can’t help wondering if the mothers know, that’s all.”

“I know,” she agreed gravely.

“Why don’t they take care of them themselves, anyway?” he blurted out, still staring at her.

Of course he couldn’t have known that she knew he was staring, she reasoned, so she looked the other way and let him. She didn’t know that she liked it, you see; she thought she was just not hurting his feelings!

“Why,” she explained thoughtfully, “I suppose they have other things to do, don’t you? Rich women, you know, don’t expect to take care of babies.”

“Oh! Rich women! Phew!” he burst out with a look of such disgust that she had to laugh again.

“Some of them are quite nice, really,” she hazarded.

“Not for mine!” he cried abruptly, and then as Dagmar approached, panting, with the key, he lifted his cap and walked away suddenly, very stiff in the back, as one remembering his high position and responsibility.

All that day the little encounter amused her in memory; she smiled, recalling his flushed, freckled embarrassment, his ingenious appeal to her mercy.

“He’s an awful nice p’liceman,” said Barbara; “but he oughtened to have forgottened his key, ought he?”

“He’s just beginning p’licing prob’ly,” suggested Marjory; and it occurred to Elizabeth that recruits must learn, somehow, somewhere, and that this was as good a place as any other to break them in.

The next morning he was at the gate as they came up.

“I’ve got it!” he cried boyishly, and held up a key. “The Cap. forgot to give it to me — what do you think of that?”

“Are you learning how to p’lice?” Marjory inquired with interest.

“I certainly am,” said he, strolling into the park. “You watch me police this park, now!”

They sat on the bench and he stalked stiff and straight round it, to the delight of all the other children.

As he drew up before them and saluted gravely, Barbara spoke: “You aren’t a blue policeman,” she announced; “why aren’t you blue?”

And Elizabeth realized suddenly that this was so; she had not noticed it.

“Because we’re sort of beginners,” he explained good-naturedly; “we aren’t fat enough for the blue uniforms, kiddie.”

“I s’pose they put you here because there’s only children, mostly?” said Marjory.

“That’s the idea.”

“What’s your name, p’liceman?” demanded Barbara.

“My name’s David,” said he. “I hope you like it?”

“Where were you before you came here?” Elizabeth asked. “What did you do?”

She spoke as she would have spoken to an interesting, well-mannered young guide or courier abroad. She forgot that he could not be expected to understand across what a gulf her interest stretched; that to him her kind young voice was only the voice of a kind young woman in a nurse’s uniform.

“Oh, I was on the rural police upstate,” he answered, flushing a little, “in Westchester County.”

“Oh yes,” she said, remembering the lean, olive-trousered men she had so often motored past; “those men round the aqueduct?”

“Yes,” he said simply; and she noticed that he didn’t say “yes ma’am” or even “yes, lady.” She liked it in him; of course those boys upstate must be of a very different class from the ordinary city policeman. That was why his voice was so pleasant and his manner only shy, only a little awkward — not common or impertinent. She remembered, suddenly, that one of her father’s uncles had been the sheriff of the little village where the Griswolds were born. And somehow this remembrance pleased her.

The girl did not realize, you must believe, with what unconscious expectation her days were filled after this. She did not realize that she came a little earlier each morning; that he entered the park as a matter of course and strolled about with her; that he waited at the gate; that he found the one open place at the north end and leaned, talking, against the iron spikes, while she sat, listening, on her bench, with Kenneth beside her.

One day, when it rained hard all day, she wondered why she was so restless, why the children tried her so, why a little paining shadow darkened everything inside her. Then, when it cleared suddenly, at half past four, she wondered again at the quickness of her shaking fingers as she pulled on their rubbers, for she was in too much of a hurry to wait for Dagmar.

“I can take them, Miss Griswold,” said the nursemaid; but she answered sharply, “No, indeed! The air will do us all good. Hurry, Marjory!”

As they entered the dripping park he swung over to them, slim flanked, with a long, young stride; why did Doctor Henderson’s short, nervous step patter through her mind?

A rubber poncho fell to his hips; he looked like some young officer on the stage.

“Oh! I never thought you’d come!” he cried; and a strange, crowded sensation pushed up round her — her — why, was that her heart? Why was she breathing so hard? Why should they laugh so, suddenly?

The sun poured out; the grass was emerald, diamond studded; the trees were full of birds. She glanced up at him, over the swinging rubber cape, and met his eyes full. They were blue eyes, and suddenly they turned into shining, piercing arrows that rained down, all fiery, into hers. It was blue and yet it was fire; it frightened her and yet it brought her peace; it threatened and yet it held.

You know, of course, what it was, but Elizabeth did not.

She knew, naturally, that people fell in love; she supposed they did it at a ball or in a gondola or while hearing beautiful music. Perhaps they looked up from some book of poems they were reading together. You see, she thought, poor child, that it was an idea — a something that attacked the mind. And of course it occurred between people of the same class.

So when he swung along beside her and looked at her — and looked at her — and her knees began to shake and that great wave rose and swelled in her side, the girl thought she was ill, and dropped, panting, on her bench; which was very damp, but she never knew it. He sat near her and it seemed to her that the side of her body next him belonged to some other person than herself—he was so near — so near —

They had not spoken. She glanced down at his hands; they were clenched on his knees. She wondered why.

“I — I never knew anybody like you,” he said, and his voice sounded husky and far away.

A lifetime of self-restraint came to help her.

“It — it cleared off, d-didn’t it?” she murmured.

He turned and seized her hands roughly; there was a wild, hot look in his eyes.

“Listen,” he said, “were you ever — fond of anybody — before?”

Then, at last, she knew. Then it burst on her. Her eyes darkened, and all the terrible, ridiculous, impossible future spread before her. Fond? Fond? She sprang up from the bench.

“You have made a mistake, I think!” she said. “Will you please go away now? Come, children!”

She never even saw which way he went.

That evening her father looked curiously at her.

“Haven’t you gained a little, Beth?” he said. “Is it that tonic?”

Mrs. Griswold also looked.

“She’s certainly improved amazingly,” she said thoughtfully. “Lou asked me what she was doing nowadays, to be so handsome.” She narrowed her eyes, and her daughter’s wavered and fell under hers.

The next day was Friday, and she stayed at home. The next was Saturday, and she bore it until four o’clock. Then she knew what had happened to her, and that she could not live so far from the park that was all the world to her. Something tore at her side and ached and cried there, and part of her lay on her bed and wept, and part of her sat on a bench and felt his hands. So that at five she crept out of her studio in her cap and cloak, and went, ashamed and secret, to watch him there — only to watch him, for she had no duty in the park that day.

She slipped through the gate as one of the last two nurses was leaving.

“The children have just gone in,” said this nurse carelessly; and “I know, I know,” Elizabeth said, and made for her bench, to weep there.

But he stalked in after her, and caught her in a grasp she had never known or dreamed of, and shook her a little and said, “I thought you’d never come!”

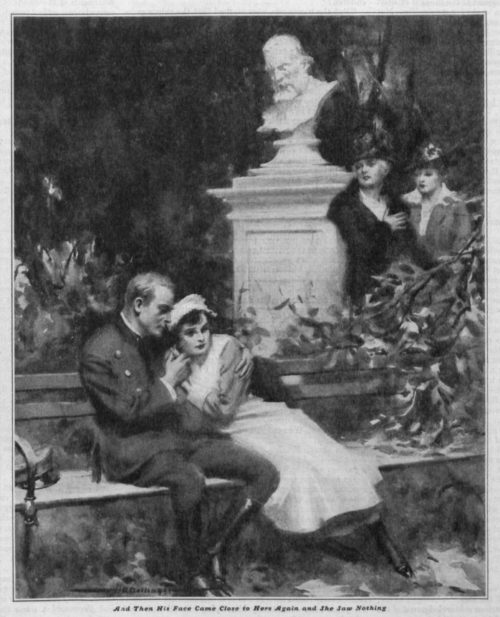

For a moment she saw the blue burning of his eyes, and then she saw nothing more, for he had kissed her.

Later she sat in his arms, in a great serene calm, and they talked.

“But you knew — you didn’t think that I didn’t mean for us to be married?” he said seriously. “You little darling, I’d never marry anybody in the world but you! There never was anybody like you! When I think of all the useless, silly, flirting fools — ”

“Perhaps you don’t know every kind of girl there is in the world,” she said, smiling adorably at him — oh, what would he say when he knew! — “but I will marry you, David dear; indeed I will. Don’t mind what anybody may say, ever. I tell you that I will.”

You see, all her culture counted at the last; and she knew that in the face of an enormous thing like this, nothing — nothing in the world — should separate them. Policeman or ambassador, a Griswold or a nursemaid, it was all the same. Nobody had ever told her that this kind of feeling existed, but now that she knew it she knew that every other feeling in the world is unimportant beside it. That strong, wonderful creature with his burning eyes was hers, and she was his. “You see, you’ve done something,” he repeated. “You amount to something. You’re a real person, you darling little Lizzie — you’re not just a dressed-up doll!”

“But — but you love me, anyway?” she begged. Oh, would he ever forgive her when he knew?

“Do I love you?” he laughed through all his freckles; “you wait till I can show you!”

And then his face came close to hers again and she saw nothing — not even her mother and her Cousin Lou, who could have touched her as she came out of the park.

Mrs. Griswold and her husband sat in a bitter silence in their motor. There was a heavy block on the avenue and they had to wait; something had broken down ahead.

“When can you see him, do you think?” said Mrs. Griswold. “Will you tell him that I am taking her away directly, and that under no circumstances can he even — ”

“Bessie, the girl’s twenty-five,” said her husband patiently; “I’m afraid you can’t really — ”

“Oh!” his wife cried, “please, please, Ben!”

“You’re sure you actually saw — ”

“Saw! Saw!” she echoed. “Great heavens; she was in his arms! He kissed her a dozen times! Saw!”

Her father winced.

“Don’t I tell you she doesn’t deny it for a moment? When I told her that the woman’s maid had told her mistress about it, and that she had had the decency to communicate directly with Lou, and that Lou and I went down to see for ourselves whether such a thing could be possible, and actually found them practically alone there, at that hour — what do you think she said? “

“I’m sure, my dear, I can’t tell.”

“‘We were engaged, mamma,’ she said; ‘wasn’t it all right?’”

Mr. Griswold sighed. He looked old.

“I’ll see him, dear; I’ll see him,” was all he said.

“And she has never buttoned her boots in her life!” cried Mrs. Griswold. “Oh, it’s too horrible!”

“I think she should have, then,” said Mr. Griswold shortly. “Look here, Bessie! Our girl would never marry a cad — I’m sure of that. I’d rather see her happy than grow up a sour old maid! There’s no doubt something can be got for the fellow to do — ”

“Oh! Oh, Ben! There he is! I see him!”

“What? Hush, Bessie, for heaven’s sake! Where are you looking?”

“There! In the club!”

In her confusion Mrs. Griswold had so far forgotten herself as to fix her eyes on a certain large window beside the pavement.

“Nonsense!” said her husband briefly.

“Ben, I tell you that was the man. And he had that very uniform on! A tall, sandy-haired, freckled fellow — very plain. Go up there and get him! Go now!”

“My dear girl, policemen don’t go into clubs. Not into the lounge, anyhow. I can’t — please, Bessie, don’t make a scene!”

“Then I’ll go myself,” said Mrs. Griswold simply.

“Oh, Lord — wait a minute,” he implored, for he believed she would do it. “Tell What’s-his-name to pull up on the corner, if this block ever breaks, and I’ll come there. At least I can get a drink.”

Harassed and gray, he wormed a way through the choked street and disappeared behind the great door. His wife sat, stony, in the motor, staring into the past. All that beautiful dainty girlhood, its perfection of detail, its costly foundations, laid through years — for what? A traffic policeman dashed through on a motor cycle, and she shuddered and cried a little, silently.

What could they do for him? Ben Griswold had a large professional income, it is true, but comparatively small investments; they lived furiously on what he made. Elizabeth and Cortwright had been their investments—and now Cort was driving a muddy truck somewhere in France, and Beth was engaged to marry a policeman! Such a quiet, steady girl — too quiet, her mother had secretly muttered in her heart.

They emerged from the block and waited in the side street among the club taxicabs.

“Extra! Extra!” yelled the newsboys. “United States on verge o’ war!”

Well, perhaps that would make a difference. If there should be war, people might forget sooner — but oh, how it cut her! How it cut!

The door slammed beside her.

“Get along home, Georges!” said Mr. Griswold. “I always forget Georges has gone. Well, Betsy, buck up, my dear; it might be worse.”

“Ben! It was the man!”

“Yes, my dear, it was. You have good eyes, if you are an old lady:”

“Ben! He — he was a — a — ”

“Oh, yes; he’s a policeman, all right. No doubt of that.”

“Ben! Does he admit — ”

“He came right up to me, my dear, and asked my permission to marry my daughter. He didn’t know who she was at all till this morning. He thought she was a nurse girl, it seems.”

“Oh! That ridiculous costume! But he knew perfectly—the idea! As if anyone could think Elizabeth was a nurse!”

“Well—I don’t know. It seems he did.”

“What was he doing — a man like that in that club?”

“He was drinking a Scotch and soda, my dear.”

“Ben! An ordinary policeman!”

“I shouldn’t exactly say that, Bessie. Not exactly. You see — oh, hang it all, Betsy, I can’t quite believe it myself, yet! Look here, dear. You remember when the commissioner swore in all those extra fellows to help out the police in case of riots or whatever — ”

“No.”

“Well, he did. He — he’s one of those.”

“Oh. Is it a better kind?”

“Oh, Lord, I suppose it is. Betsy, old lady, you certainly had a bad time. I — I felt it myself. But what could I do? You wouldn’t let me talk to her. I wonder what she’ll say?”

“Say? Ben Griswold, what do you mean?”

For his eyes were strange, his voice was shaky and sounded like the voice of the young man who had asked her to marry him 27 years ago, when she was 24.

“I mean when she sees this,” and he stuck his hand into his waistcoat and dropped a flash of white light into her lap.

It was of glass apparently, but blinding, and about the size of a five-cent piece.

“He seems very fond of her, Betsy. He says she’s the only girl he ever looked at; and, by George, I nearly believed him!”

“But, Ben — ”

“You never even asked his name, my dear.”

“But how — ”

“His name is Craigie — David Craigie.”

“N — not — Ben, it’s not the David Craigie?”

“I’m afraid it is, my dear. I wish he didn’t have quite so much, Bessie. It’s a pretty heavy responsibility, you know.”

She stared at him, stupid in the great revulsion.

“He said he got sick of signing checks all the time, and not doing anything; he’s a shy sort of chap, Bessie. He equipped an entire volunteer company up at that big place of theirs on the Hudson, you know, and still he couldn’t feel like anything useful, he said, so he went into the rural police volunteers up there and then joined the reserves here. He’s very quiet, you know— nobody knows him much.

“He told me he hated the sight of a girl till he saw Beth. Suspected ‘em all, I suppose. Sort of a serious chap — just the sort for her, I should say. Nothing very showy, but all there.”

“But, Ben — that old Mr. Craigie has — how much money has he, Ben?”

“A good deal more than anybody ought to have, my dear,” said her husband soberly; “somewhere round forty or fifty million, I’ve heard. We didn’t discuss it. He told me — young Craigie did — that Beth had found out somewhere how much a roundsman got a year, and explained to him how they would manage to live on it — twelve hundred, I think it was. He was thinking all the time that she thought it would be a rise in the world!

“And now,’ he says to me, ‘now I know what she was really thinking — my God, I love her more than ever, Mr. Griswold!’”

Mrs. Griswold was not listening, one fears. She was staring at the ridiculous shiny ring of white fire in her hand. Later, she cried a little and kissed her husband in the motor and he patted her shoulder. The last 24 hours had been hard for her, as you will understand.

So Elizabeth was married, in white satin, very plain indeed — to draw the eye to the great rope of pearls, her bridal gift from her husband. The biggest was about the size of a big white grape, and they ran down from that through moth balls to the little ones at the clasp, which were the size of peas. She looked very lovely and distinguished, and not at all tired; perhaps because she had refused to bother about anything, before the wedding, and passed most of her time in Gramercy Park. Marjory and Barbara were flower girls, and Kenneth sat in a front pew and talked with imaginary birds all through the service.

It is difficult to point a moral against foolish mothers from this story, for though Mrs. Griswold was undoubtedly foolish to have brought up her daughter to marry a multimillionaire, yet, you see, she did marry a multimillionaire. Which was, nevertheless, no credit to Mrs. Griswold, inasmuch as Elizabeth supposed herself to be about to marry a policeman!

After the wedding the reporters all rushed off to Mr. Craigie’s special car, which lay conspicuously in the Grand Central Station, en route for his Adirondack camp. A tall man and a lady in a thick veil climbed hastily into this car, and nobody dreamed that they were Mr. Craigie’s man and Mrs. Craigie’s maid.

And so, naturally enough, nobody dreamed of following the young couple to a modest but comfortable apartment overlooking Gramercy Park, which had been cleaned and polished to a state of supremacy by Dagmar, and vacated just before the wedding by the wondering Barbara and Marjory. Kenneth never wondered at anything.

They sat on a little balcony ringed round with geranium boxes and looked out over their park, sleeping in full white moonlight.

Will you laugh too much when I tell you that she wore a white cap and bib and apron, and that he was in the full uniform of the Police Reserve?

Of course you and I wouldn’t have done that on our wedding night, but they were not 25, either of them; and, though nobody knew it, they were a little romantic!

“I shall always love you in it,” she said, and kissed the buttons, which simply shows you how many extra kisses she had.