© SEPS

Originally published November 30, 1963

Every night, before he went to sleep, he saw a parade passing right before his eyelids. There was the public librarian, and Mr. Cain of Cain’s Dime Store, and his boss down at the shipyards and the town drunk and the preacher. Everyone in Balton was there, smiling gently and slowly, nodding as they came abreast of him — everyone who’d known him since he was born. Against the surrounding darkness their faces were bright and warm; their pace was stately, and they wore triumphant reds and purples that swept the ground as they walked past.

He took up his pistol and he shot them all down. One by one they fell, leaving not bodies but simply empty space, like a wooden duck would leave in the line at a county-fair shooting gallery. Each time he shot there was a kick from the gun that shook his whole body, but it left him tired and peaceful and his mind was cleared for sleeping.

He woke that morning with his mother saying “Sammy” in the doorway, standing there already anxious and frazzled, with her hands pulling nervously at the cord of her bathrobe. “You’ll be late for work, Sammy,” she said.

There were bars of light across his face from the morning sun coming through the blinds. He groaned and turned away from the light, but his mother still stood there, knowing he wasn’t awake enough yet for her to leave him alone.

“You getting up?” she said.

He sat up and peered at her, and only then did she leave. The sound of her scuffing slippers slid farther and farther away, down the narrow hallway and into the kitchen, where coffee would be perking now to start off Sammy’s day. He turned back toward the window and peered out, his young face blank from sleep and his hair tousled.

Below his window and down the slope lay Balton Harbor, with the Balton shipyards and the little town of Balton cuddled neatly around the black water. He could already hear the harbor noises — the far-off hum of boat engines, the jagged buzz of electric sanders and saws and drills, the pealing of the bell in the clock tower that stood on Samson Hill. As he dressed he separated the noises from one another, naming them, knowing each sound exactly and knowing if anything was different today. A yawl went by; he knew without looking whose it was, and that the engine would surely be in the shipyards within a week for him to work on, if its owner had any engine sense.

He put on his blue coveralls, which were stained with grease from probably every boat in Balton Harbor, and splashed cold water on his face before he went to breakfast. The water made his eyes suddenly wide-awake, and things struck him more clearly. When he came to the kitchen and saw his mother’s red-checked tablecloth, he blinked a couple of times at the sharpness of it.

“What you want for breakfast?” his mother asked.

“Just coffee, Mum.”

“Nothing else?”

“Coffee and a couple of cigarettes,” he said.

He pulled out a chair and sat down with his legs sprawled out in front of him and grinned at his mother.

“Sammy, you got to start eating more.”

“I’m not hungry yet, Mum.”

“You will be. How’d you like some bacon?”

“Nope.”

“Some coffee cake?”

“Nope.”

His mother poured him a cup of coffee and sat down opposite him, her hands clasping the table edge and her whole face strained toward him. She was a very thin woman, the kind that went whole nights without sleep. Her husband had had itchy feet and died someplace down South, a thousand miles from Maine and from her, and her older son, Phillip, had inherited those itchy feet and was gone from her forever. Anyone who didn’t know these things about her could have told it from her eyes, which seemed to be asking the same question over and over, and from her hands, which kept reaching out and touching people, almost grasping them, and then by sheer will were drawn in again quickly and folded in her lap.

Only once during breakfast did she touch Sammy. She reached out and touched the top of his head, where his hair grew thick and fair, falling down over his forehead. He smiled at her, and she put her hand on the table. “I could scramble some eggs,” she said.

“No, thanks, Mum.”

He stood up and took his cap from the counter, and she followed him to the door. “Be careful,” she said.

“I will.”

Your Story Here!

The 2018 Great American Fiction Contest is now underway. Enter for a chance to win $500 and have your work appear in the magazine that published F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, and Kurt Vonnegut!

To enter, visit saturdayeveningpost.com/fiction-contest.

He set off down the little path toward the harbor, and his mother stood watching after him. She watched the bobbing of his head, the blue of his coveralls flashing through the weeds, and then she waved at his back and went inside, smiling a little, a crease between her eyebrows.

Halfway down the path, Sammy was joined by a group of children, the same ones who trouped behind him on every other day of the summer. A little boy named Porter led them; he came silently up behind Sammy and said, “Hello, Sammy,” and tugged gently at the sleeve of Sammy’s coveralls.

“Hello, Sammy,” the children said.

“Hi,” Sammy said. He took off his cap and put it on Porter’s head, backward, so that the visor hung down the back of his neck, and Porter grinned and straightened the cap around right.

“You going to the launching?”

“Sure am,” Sammy said.

“You going to be in the launching?”

“Yep.”

Porter drew in his breath with a little whistle and the other children echoed him, seriously, a chain reaction down the line. “Don’t I wish I were you,” Porter said.

Sammy grinned. “I’ll just be on the boat when she slides out,” he said. “Along with Barney. She ain’t got her masts in yet, so we’ll run her with the engine over to the wharf. It’s the Hope’s old engine, so we can start ourselves without the factory man.”

“You seen her up close yet?”

“Ayeh.”

“How big is she?”

“Oh, little. Thirty feet maybe, I don’t know. Prettiest boat they’ve made for years, though.”

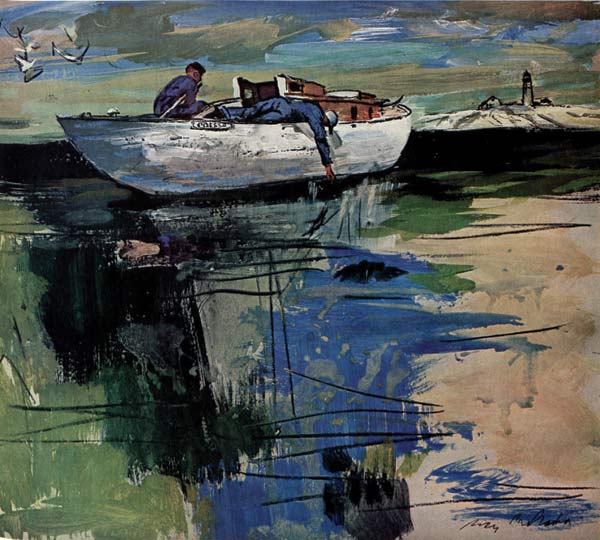

The path descended a rocky bank so steep they all had to run as they went down. Rocks and sticks scattered beneath them, and their shoes slid. One of the children, the smallest little boy, stumbled and came sliding down most of the way on his stomach, but he didn’t cry, just looked up with round eyes while the other children dusted him off. Sammy handed him a handkerchief for his hands and looked off toward the harbor, where a few sails were already up and some fishing boats were puttering out to sea. It would be a good day for boats. The water gleamed in the sun, and the shipyard wharf, running up one side of the harbor, seemed new and almost white.

“I can spell etiquette,” Porter said at his elbow.

“Good for you,” Sammy said.

“Can I go on the Odessa with you when they launch her?”

“Nope.”

He took the cap from Porter’s head and put it on his own, pulling the visor down over his eyes so that he wouldn’t have to squint against the glare of the water. “It won’t take more than 15 minutes anyway; you wouldn’t have time to notice you were on her.”

He ruffled Porter’s hair and grinned at the other children. “So long,” he said.

“Can we walk you back home again tonight?”

“If you want.”

They scattered away, with little cries like far-off sea gulls, and their feet pattered up the bank. The little one who had fallen before fell again, not very hard, and when Sammy saw that he wasn’t hurt he went on his way toward the shipyards.

The shipyards were mainly the one wharf, already warm from the sun, with a cluster of small boats tied up to the pilings. Behind that was a great barnlike building, opening on the outer harbor, where the shipbuilders worked. Sammy spent most of his time working on boats already out on the sunny water, but they were launching the Odessa this morning, and he climbed over the rocky hillock that separated the wharf from the big shed and walked inside, into the cool darkness. Everything smelled of new lumber. The first thing he saw was the network of wood that was to be another boat someday — even better than the Odessa. It was like a fisherman’s net, tight and graceful. Just looking at it, he could feel the shape on his fingertips, and he stared at it a long time before passing on to the Odessa.

Around the Odessa there were maybe 50 people, all crowded together, leaning forward so they could see the iron tracks that were to slide her into the ocean. Sammy wormed his way through them, trying to keep his greasy coveralls away from the people nearest him.

“There’s Sammy,” a girl said.

Some children waved to him from a rafter, and the adults turned to smile at him.

“How’s your mother, Sammy?”

“She’s fine, ma’am.”

“Why don’t you ever come by for supper anymore?”

“Sammy, what you think of this boat here?”

“You going to be on her at the launching, boy?”

“Hear the owner can’t even sail himself; you going to run the engine?” Sammy worked sideways through the people, smiling at them as he passed, and dropped into the pit above which the boat was to begin her journey.

“How’s it going?” he asked Barney.

Barney looked up at him. “They’re greasing the tracks,” he said. “About five minutes more, I guess.”

He was a small man, gray and wrinkled, wearing mechanic’s coveralls exactly like Sammy’s. He was so small that he had to look up at everyone, and his forehead had taken on permanent creases that made him look constantly surprised. “Come and meet Mr. Flint,” he said. “He’s the owner; might be a good man for you to know if you ever want a job away from here.”

Mr. Flint was a big, red-faced man. Sammy had seen him standing around the shipyard on sunny days.

“You’re Sammy, huh?” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Flint shook his hand, looking into Sammy’s face. “Heard a lot about you,” he said. “You’re kind of the fair-haired boy around here, from what they say.”

“Best man I’ve got,” Barney said. He looked surprised at himself, and clamped his mouth shut again.

“Think you and Barney can bring her in okay?”

“Yes, sir,” Sammy said.

“We’ll do it,” Barney said. “Sammy knows how. Would’ve gone off to college, Sammy would, if it weren’t for taking care of his mother and such.”

“Well, I’ll trust her with you,” Mr. Flint said. “If we could all get ready now … ” and he went stomping off, over to where old Captain Harding was showing Mr. Flint’s wife about the bottle of champagne.

When Sammy was actually on the boat, he could see everything that was taking place. The children on the rafters were quarreling about who would get to blow the bugle, the adults were pressing closer and closer, and Mrs. Elliott’s 2-year-old fell into the pit by mistake. They had no sooner recovered him than a sawhorse got dropped in, too, and a group of little boys clambered down to pull it out again. At the bow, Captain Harding was having the time of his life, swinging the champagne bottle as if it were a baseball bat to show Mrs. Flint how to do it, while Mrs. Flint, dressed all wrong in a bare-backed sun-dress and little bits of nothing for shoes, stood gracefully by and looked worried.

“All set, Sammy?” someone asked.

And a group of girls in the back called, “Good-bye, Sammy!” and waved thin, bare arms above the others’ heads.

Sammy smiled and sat down on the little deck. He could feel all around him the tightness of the boat, the hard strips of teakwood that made up the deck, and the graceful curves rising before him and behind him. It was the kind of boat you could hug. If he lay on his belly and dropped his arm over the side, he would feel that curve, warm and living, like the curve of a cat, something that would press against his hand. Maybe when he was out in the harbor he could hug her. Barney wouldn’t care.

They had removed the blocks from the dolly under the Odessa and only her own weight held her now. Barney had climbed aboard. At the bow, Mrs. Flint picked up the bottle of champagne, wrapped in ribbons and swinging by a ribbon from the bowsprit. “She’ll never smash it,” Barney said.

They could not see her swing it, but they could feel the tiny shock against the bow as it hit, and then the air pumps working that would move the dolly and set the boat free down the tracks.

“By God, she broke it,” Barney said.

The boat moved. It made its way slowly down the black greased tracks, and Sammy, looking over the neat white deck rails into the mechanized ugliness of those tracks, felt like some god, standing where no one else could stand, above all the ordinariness of iron and boat grease. The bugle calls began. He looked up into the rafters and saw that the children were sharing the bugle, passing it up and down the line, each blowing a blast in turn. The sound was high and very clear, and it pierced straight through him.

There was a moment, as the Odessa hit the water, when all of them held their breaths. But she barely paused, and then slipped on in. One second she was heavy and earthbound, and in the next she took heart and floated off, lilting up and away. And now the bugle really let forth, full of joy and relief and a strange kind of tenderness, echoing down from the warehouse and sounding out over the water, speeding the boat away and yet, at the same time, sadly, calling it back.

Sammy and Barney just sat there for a minute; nobody could blame them for that. They listened to the peaceful slapping of water against the boat, and to the gentle sort of breathing noise that every good boat makes. By then she was fairly far out with the tide, and the wharf seemed only a slender matchstick in the harbor.

“Got to take her in to the wharf, boy,” Barney said. “They’ll put the masts of her in after lunch.”

“Okay,” Sammy said.

Barney stood aside for Sammy to go to the stern and start the engine. It was a neat, tight little engine; Sammy let it idle awhile just to hear the sound of it. Then he pressed the gas and swung the tiller, heading out toward the open sea.

He couldn’t have said beforehand that that was what he was going to do. He had thought he was going to follow orders and work it the way he always had: turn her into the inner harbor, treat her gently, tie her to a piling, and leave her there. But what he did instead didn’t surprise him; that was the strange part. He pushed her for all she was worth and set out for the wide Atlantic, and his face was as calm as if he were asleep.

“Where you going?” Barney called. He was looking at Sammy mildly, thinking he was only playing. “Turn her, Sammy; no games now.”

“Ain’t a game,” Sammy said.

The wind was full in his face. He opened his mouth to taste the wetness of it and gave the engine all the gas it could take, to make the wind blow harder. It wasn’t an engine built for speed — probably it would only be used to putter her safely home at the end of a day’s sailing — but it made good time, and they were leaving Balton far behind.

“You gone out of your head?” Barney yelled.

He reached to grab the tiller, but Sammy held on and the boat only swayed to one side.

“Sammy,” Barney said, “Mr. Flint’ll be hopping!”

He sat down on one of the deck seats suddenly, and his face was small and gray.

Sammy switched the engine off.

“Don’t know what we’ll do,” Barney said. He seemed not to have noticed that the engine was off; he put his head in his hands and groaned.

Everything was very still now. The water lapped against the sides, and the sea gulls called behind them. Sammy leaned forward and touched Barney gently, and said, “Hey, Barney, we can go back.”

“I just don’t know what come over you,” Barney said.

Sammy leaned over the other side of the boat, away from Barney, and tried to touch the water with his fingertips. “I sure did like those bugles today,” he said.

“You had some kind of spell maybe.”

“Every time I hear a bugle, it goes straight sharp through me. Sometimes I think I could build a hundred-foot schooner by hand, and pound in the nails with my teeth, just to hear those bugles blowing when she slides down the tracks to the sea.”

Barney moved over beside him in the stern, being as quiet as possible about it, and started the engine again.

“You know, Barney, this town has got more damned bugles in it. All kinds of bugles. Go walking down Main Street and the whole street is full of them — hundreds of them, blowing too high for your ear to hear, and tightening you together, calling you like your mother calling you home for supper. And who’d go anywhere, with all those bugles blowing? Even if you’re crying to go, who could go?”

He was talking with his chin resting on the side of the boat, and the smell of fresh varnish right beneath his nose. He couldn’t see Barney’s face. There was no telling if Barney heard him or not, because Barney had the engine going and the boat was turning home. The wharf grew larger and larger, and Sammy turned to watch it.

“It’s such a damned loving town,” he said. “I didn’t really want to hear those bugles. Hey, Barney, you ever heard those bugles?”

But Barney was bent away from him, admiring the engine. When he straightened up and caught Sammy staring at him, he called, “Don’t worry, boy, I got an idea back there. You and me heard something funny in the engine, see, moment we started her up. So we took her out to check on it. Okay?”

“Sure,” Sammy said. He smiled and said, “Sorry, Barney.”

“Oh, hell, it’s okay.”

They came in alongside the wharf, crowded now with Balton people who had stayed to see Sammy and Barney bring the boat back. Someone grabbed the bow line. A man said, “How’d it go, Sambo?” and reached down to help him up. “Quite a ride for your money you got there.”

“Thinking of leaving us, Sammy?”

“How’d she run?”

They helped Barney up and then stood around with nothing to do but look at the Odessa and talk about other boats they remembered from the old days.

Sammy stopped listening to them, or to the breeze rushing past his ears. In his own private echoing silence, he polished the pistol of his dreams; he held it, heavy and shining, in the farthest reaches of his thoughts, while above him the sea gulls swung and called beyond the shore.

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1941, Anne Tyler won a Pulitzer Prize for her novel Breathing Lessons (1988) and has had several works, including The Accidental Tourist (1985), adapted to the big screen. At 22, she wrote “A Street of Bugles,” which appeared first in the November 30, 1963, issue of the Post. The story “grew out of a summer I spent in a small coastal town in Maine,” Tyler said. “One of the ways in which the town seemed unusual was that no one, not even the young people, appeared to want to leave.”

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now