This is the story of a spoiled girl who hadn’t the least idea that her parents had spoiled her. Nor, for that matter, had her parents any such idea — far from it. They would have told you that the amounts of money, time and worry they had spent on the child were beyond belief. She had been brought up—for some inscrutable reason known only to her sort of parents — to speak French before she could speak English; she played the piano rather well, the violin rather badly; she danced beautifully.

German she began at twelve, Italian at sixteen, when they took her to Florence; at one time she joined a Spanish class, but shifted to barefoot dancing later, and after that to hand-wrought jewelry.

“Miss Griswold,” her dancing teacher said of her, “is a great puzzle to me. She ought to be so much more of a success than she is. She really dances extremely well, but somehow she never looks the part!”

And that was true; when you watched Elizabeth swaying through a Spanish dance you decided that her regular features were really rather cold and classical; but when she lifted her left foot, in that attitude of one who has unwarily stepped on a toad, so common to the Greek friezes, and paused, listening, you realized that her eyes were too brown — or something. When her hair fell loose, it was too straight; when, on the other hand, it had just been waved by the trusty Marcel method, it looked too artificial.

Was it self-consciousness — too much New England blood with not enough New England convictions? Her mother never knew.

She had been born in New York and, except for the Maine coast and Florida, knew little else of her country till her twenty-fourth year, when their family physician in despair had suggested the air of the Rockies; and Elizabeth, conscientiously attired in riding breeches and sombrero—she would have worn “chaps” if necessary — rode a vulgar little cow-punching bronco across the plains for six weeks. It seemed to do her good, they thought; but still she was listless, and though perfectly willing to go back to the ranch, if they liked, she was equally willing to stay in New York and take up something else. She had been out in society for five seasons, and no man or boy had proposed marriage to her.

Now, why was this? She was not in the least bad-looking; distinguished, rather, in a regular New Englandish way, with a clear profile, clever, thoughtful eyes and a sufficiently mobile mouth. She was pale, it is true, but are not most American girls rather pale than otherwise? She was a little too thin perhaps, but these are thin years, and many a luscious little fat girl envied Elizabeth her hipless, slim-ankled silhouette. She had been super-educated possibly; but on the other hand she had been sedulously taught to conceal this, and could talk as many banalities to the minute as any of her friends. She sat behind her mother’s tea urn, charmingly dressed, and listened as interestedly as possible to the account of your surgical operation, your Pekingese or your baby—giving you, meantime, just the dash of cream or slice of lemon you had asked for. She wasn’t prickly or catty or piggish about men or rude to her elders; nor was she a prig. And yet—and yet —

As a matter of fact, I believe her to have been the chief sorrow of her mother’s life. Mr. Griswold would have been surprised indeed to hear me say so, for he had paid for all the subjects Elizabeth took up, and was very proud of her. Sometimes he may have wondered just why she should have to take up so many, and what she found to enjoy in them; but he paid for them, just as he had paid for her expensive coming-out party and her riding boots and her teeth-straightening and her lectures on gardens and wild birds.

He didn’t even complain when Mrs. Griswold decided that Elizabeth ought to have a studio.

“B-but can she paint?” he called, round-eyed, through his dressing-room door, struggling with his third white tie.

“Of course not, Ben; she doesn’t pretend to.”

“Going to learn?”

“Oh, no — it’s not that, exactly, dear. A good many of the girls have them now, and I thought it might make her feel freer, perhaps less tied down.”

“If Beth had been born an orphan she might have amounted to something,” one of her friends once grumbled. But she was not an orphan; she was hopelessly a daughter.

“It’s the darnedest thing about Beth Griswold,” I heard one of the girls of her year murmuring one day when we were both sitting on a float fifty yards from the pier, with our feet hanging comfortably in the water.

“Huh?” the other girl inquired elegantly, stuffing sodamint tablets—for which she had a passion — into her moist little red mouth. Neither noticed me, for I was over thirty.

“Huh?” the other girl inquired elegantly, stuffing sodamint tablets—for which she had a passion — into her moist little red mouth. Neither noticed me, for I was over thirty.

“It sure is,” pursued the first thoughtfully, wriggling her toes in intricate patterns.

“She’s a peach of a swimmer, but nobody cares a whoop somehow.”

“Oh, yes, she can swim all right, all right — but she doesn’t get ‘em, does she?” agreed the second, through an ecstatic mouthful of soda mints.

“No pep!” concluded the first succinctly. “Dead man’s float — let’s?”

And they fell off the rocking platform simultaneously, assuming ghastly attitudes. They were high-stand graduates from one of our leading educational institutions for young ladies, and I supposed them to be recuperating their minds from the strain of a too strictly censored vocabulary, and gathered that they deplored in their friend a degree of personal magnetism and vitality incommensurate with her undoubted aquatic accomplishments.

That was the August of 1914, and all over the astonishing little country of Belgium blood was running.

Mr. Griswold was worried, and passed, as the months rolled by, from worry to horror, and from horror to alarm. At last he began to write letters to the Times, and read them to men at the club. Mrs. Griswold promptly became enmeshed in a web of committees — when she wasn’t serving on one she was forming another, and rarely lunched at home. Cortwright Griswold, their only son, hammered furiously at his parents for permission to drive an ambulance in France; Katy, Mrs. Griswold’s maid, who had buttoned and hooked Elizabeth since the day when she blossomed from safety pins into buttons and hooks, drew out all her savings and began sending them to Ireland; Georges, the chauffeur, got his papers suddenly and departed to join his regiment somewhere in the Valley of the Marne.

More months rolled by, and shoes became sickeningly costly; and suddenly even satin slippers, which they couldn’t very well be wearing in the trenches, one would suppose, took on a value that forced one to consider one’s allowance rather carefully.

“Disgusting! Simply disgusting!” said Mr. Griswold irritably. “I can tell you, my dear, the day for pearl-gray satin slippers at seventeen dollars a pair is rapidly passing!”

“I know, Ben; I know,” Mrs. Griswold replied pacifically; “it’s dreadful. But what is the child to wear? She can’t very well dance in tan boots. And all these dances are for hospitals or Belgian babies or things like that.”

Mr. Griswold explained, briefly but plainly, his feeling for such dances.

“I know, Ben, but people won’t give money without something like that. That orphan-baby dance last week made thirteen hundred dollars.”

“Oh, well — ”

And more months rolled by.

Suddenly Cortwright was at Plattsburgh, and Mrs. Griswold was delighted, and her husband grew silent and absorbed, and stayed longer at the office. Everybody began to stand up jerkily when The Star-Spangled Banner asked them, Oh, say, could they see, at restaurants and theaters. And quite the nicest people went to the movies to follow the war films. Elizabeth got very tired of watching the Czar climb down the trenches.

Indeed, she found herself very tired, somehow, just as all her friends were growing so busy and so busy and so busy. She took the Red Cross nursing course, naturally, and one in first aid, but the Red Cross teacher, a brisk, flat-chested woman with a strong Western accent, advised her very frankly against going into any but the most elemental mysteries of her fashionable science.

“You see, my dear Miss Griswold, it’s so much a matter of pursonal’ty,” she said, “nursing is; and reelly, I must say I don’t think you’ve got the right pursonal’ty for it — if you get my idear.”

The class in first aid was even more unfortunate. It went on in the parish house of a fashionable church, and a nice old family doctor, who had brought many of the young ladies into the world, gave them the lectures. Somebody was to provide a choir boy to be bandaged, but he was an elusive choir boy and missed most of the mornings, and a few of the cleverest girls got all the practice in resuscitation and splints by using the obliging members of the class as victims. Afterward a very severe young surgeon with a pronounced German accent burst in unexpectedly and examined them—two questions apiece. He wore his stiff black hair en brosse, which is always so disconcerting, and whatever he asked you, the answer turned out to have been “cracked ice”; which the nice old doctor had hardly mentioned.

Elizabeth’s questions were convulsions in infants and sudden bleeding from the stomach; in the first case she forgot the cracked ice, and in the second she failed to see how it could be usefully applied, unless the patient could be induced to eat it, and as she presupposed him to be unconscious at the time, she didn’t suggest it. When they turned up at the parish house the next week to get their diplomas, they were met by a typewritten slip, sandwiched between the choir rehearsal and the Ladies’ Auxiliary, which informed them that none of the class had passed!

Elizabeth didn’t care very much; it had been her mother’s idea. She went languidly to a set of talks on the Balkan Situation, where everybody knitted; and later joined a committee for collecting old linen for a big, new surgical-dressings committee. But the district given her was away up on the West Side, and as she couldn’t take the motor on those days and wasn’t allowed to use the subway, she stood so long on the corner in the rain waiting for the bus that she caught a heavy cold, which ran into tonsillitis — it was, you will remember, a tonsillitis year — and by the time she could get out again her place on the committee had been filled by an energetic girl with an electric runabout of her own.

The months rolled by and there was getting to be quite a little list of Americans who had been killed, in one way or another, on account of this horrible European war, and many of her friends wore little button knots of Allied ribbon. Mrs. Griswold was forced in the interests of digestion to ask guests not to mention the President if they could help it, it made Ben so angry; and Cortwright, who became 21 on a Tuesday, ran away to France with one of his cousins on the Thursday following, and drove his new birthday car through the second war zone, filled with hospital supplies. Mr. Griswold scolded him soundly by letter and boasted of him at the club, and his mother turned his bedroom and study into a shipping depot for tobacco for the trenches and old clothes for various devastated regions.

Mr. Griswold became chairman of one of the relief committees at the club and secretary and treasurer of a Harvard Alumni committee, and went to a great many men’s dinners. As Mrs. Griswold rarely came home to luncheon now, and the cook’s son had recently joined the National Guard, which for some reason preyed on his mother’s mind to such an extent that she confined herself to what she called some little thing on a tray for Miss Elizabeth, the girl, who had never been much interested in her food, began to grow really thin and you noticed her cheek bones.

I mentioned this, incidentally, to Mrs. Griswold, who became extremely vexed and left me with the impression that Elizabeth was very unpatriotic to have grown so thin, and I nearly as much so to have remarked it. A bottle of port-and-iron was placed on the sideboard, out of which the girl very sensibly poured a little over the roots of the table ferns now and then. I call her action sensible because iron disagreed with her digestion — feeling, indeed, like a sharp three-cornered stone in her chest—and the port went to her head.

The months rolled on, and now a strange thing occurred: utterly aside from Europe, and the President, and the ridiculous state of the Army, and the probable effect of German propaganda on the Irish, something happened to Elizabeth herself! Something, actually, which her mother had not planned and her father had not paid for — something she stumbled into all alone!

It happened in this way:

She was in the habit of going to her Cousin Lou’s once a week or so, to play with the children when their mademoiselle went for her weekly afternoon out, an afternoon devoted nowadays to packing great bales of comforts for the American Fund for the French wounded. There had always been a Fraulein until now, but when all the Frauleins turned out to be without doubt German spies—;they spent their time in giving important Germans maps of their employers’ houses—Cousin Lou turned away hers, weeping—she had been the most marvelous packer, my dear, and knitted the most beautiful sweaters, and the baby cried for a week! —and engaged Mlle. Dupuy, who slapped the children, one feared, and had headaches; but then, think what France did for us when we were fighting for our freedom!

Elizabeth was really fond of children and got on well with them. She sang them funny little French songs that her old bonne had been used to sing to her: Maman, les Oils bateaux qui s’en vont and Il pleut, it pleut, bergere; she tied bandages on their wounded soldier dolls; she even had tea with them occasionally.

One afternoon Lou was having a meeting at her house, and mademoiselle had agreed to stay with the children, as it was raining. Elizabeth, who had come as usual, strayed into the meeting, at her cousin’s earnest request, and listened politely to the speaker, an eager, dynamic little creature —nobody in particular, really — with a solid genius for organization and inspiration. She had been a trained nurse, it appeared, had married a doctor, and lived in an apartment on Gramercy Park. She had raised thousands of dollars for the orphaned children of France, and did mighty fieldwork as a missionary for that cause. Indeed, she threw out, in passing, the desire of her heart was to dedicate herself entirely to that work and direct it from the city headquarters all day long, but that she could not feel justified in leaving her three children, the oldest not yet seven, to the care of servants.

“Think, only think!” she cried, throwing out her arms with an impassioned little gesture, “think what I could do for this wonderful work of ours if only some one of the hundreds of nice women in New York who are of no earthly use to anybody would come and take care of my children! I don’t say wash them and blow their noses for them and tidy their rooms — I can afford a good nurse for that. But my husband doesn’t approve of schools for children until they are eight years old, and I’ve always been with them a great deal; I don’t want to leave them with servants. Somebody ought to organize all the women who haven’t any special gift and release those of us who have! They ought not to expect any pay” — her smile was half whimsical, half fanatic —“they ought to feel that they’re just doing their bit. Don’t you agree with me, ladies?”

They laughed and applauded enthusiastically; her ardor was contagious. “Heavens! I wish she could reorganize the office for us!” murmured the woman whose name headed the engraved letter paper of the great charity; “she’s a little wonder!”

Then they moved and seconded for a few minutes and went on to the next thing — all, that is, but Elizabeth. She sat staring at the little speaker, and later followed her quietly into a Madison Avenue street car.

“I am Elizabeth Griswold,” she explained, “and I wondered if you would be willing to let me take care of your children while you were at headquarters? I could come every day if you liked. Lou Delanoy is my cousin.”

“I think that’s perfectly fine of you, Miss Griswold,” cried the little wonder delightedly. “I should like to be at headquarters from nine till five, except Saturdays, this month anyway. Things are in an awful mess down there. I’ll have Dagmar bring the children right down to the park to you on fine days, and then she can address circulars for me and attend to the telephone. I knew there must be hundreds of girls who would like to help me out, but I didn’t expect to find one so soon. And you realize, don’t you, that you’ll be doing every bit as much in your way as I shall be in mine?”

Elizabeth smiled vaguely.

Elizabeth smiled vaguely.

“I wanted to do something,” she said. “Shall I come tomorrow?”

Her next step I am almost ashamed to tell you, if you happen to be a sensible, practical person: She went to a most expensive specialty shop on the expensive avenue and asked for nurses’ uniforms. Blue ones she purchased, with bib aprons and little caps that stood up in the front; and when the attendant asked “Will you like to look at the capes and bonnets, miss?” she nodded seriously.

“They’re thirty dollars — but of course the war — ” murmured the attendant; and Elizabeth, to whom it had never occurred that a coat could be purchased for thirty dollars, said gravely “Of course.”

“The nurse will be about your size, miss?”

“Yes—about my size,” said Elizabeth.

Now of course you and I would never have been so foolish. We know that one can sit in Gramercy Park and superintend the play of three children in whatever dress she happens to have on at the time — a bathing suit, as far as that goes, were it not for the park regulations. But Elizabeth, you must remember, was only 24, and had, like most people, her own particular little romantic tendencies. They may not have been yours or mine, but they were hers; and, besides, all her friends were fussing about some kind of uniform or other — this was her uniform.

She never, in her wildest dreams, could have imagined what that uniform was to do for her!

At eight the next morning she stood by her mother’s breakfast tray.

“I’m doing some work for the Relief Reorganization Committee,” she announced briefly; “I’ll be busy all day, probably.”

“That’s good,” Mrs. Griswold replied, her eyes on her mail; “there’s nothing like an interest — Oh, what a fool that stenographer is! I shall simply have to have a special one for my department, that’s all. Remember, dear, we’re dining at seven tonight—your father had to take a box for that Serbian Relief concert. I asked Doctor Henderson.”

Elizabeth left the room in silence, with her lips pressed together. She understood perfectly well about Doctor Henderson. He was forty and distinctly baldish and a little tiresome. Adenoids were — or was — his specialty, and he danced painstakingly, with a tendency to perspiration and counting the time under his breath. Nobody had ever suggested that since she was nearly 25 and since he was the only unmarried man — at least he was a widower — who had ever shown the least interest in her, and since he was doing very well indeed and would undoubtedly do much better, why, he was a very desirable extra man to sit in the box or go on to a dance later. Nobody, I say, had ever so slightly suggested it, but Elizabeth understood very well. She was serious; Doctor Henderson was serious. The inference was obvious.

Of course it all seems very queer to me, if you ask me. Why a young person should be brought up like a duchess in order to marry a surgeon at the last, I can’t see. He was making, we’ll say, 20,000 a year; maybe a bit less, maybe a bit more. But we all know what rents are in New York, and a doctor must have a decent house in a decent part of the town if he wants to cut out rich children’s adenoids. And Elizabeth didn’t know whether chops grew in the sheep’s cheeks or in its legs. And I told you what her evening slippers cost. She had no idea what wages parlor maids get nowadays or what coal costs a ton. Somebody had always turned on her bath for her, and one day when her little satin bed shoes had not been placed by the side of her bed, she had been obliged to sit on her toes and call to her mother to ring for Katy to ask where they were! It is not that she was lazy at all, I assure you, but it never occurred to her that it was a part of her duty to hunt for her bed slippers.

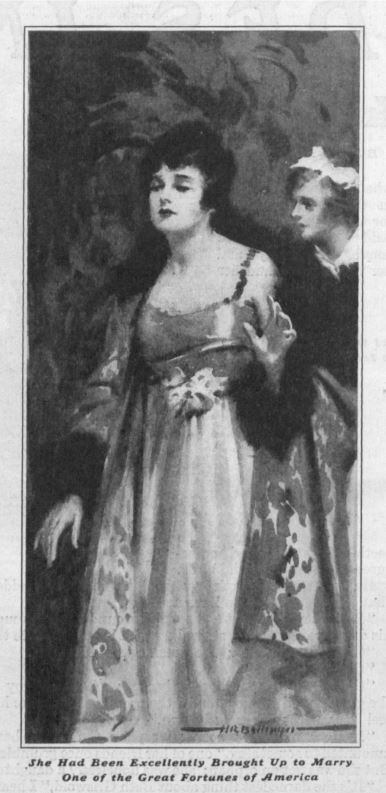

In other words, she had been excellently brought up to marry one of the great fortunes of America; or perhaps it is only fair to add that she would have been useful to a brilliant young attaché to an important foreign embassy — but even he would have had to be reasonably well off, don’t you see?

The three little Gramercy Park children didn’t worry over all this, however. They were nice children and they took to Elizabeth promptly.

This isn’t a bit like the old novels, you see; there is no suffering governess involved, patiently bearing with the rudenesses and cruelties of the brutal and the rich. No; it is really true that children brought up by their mothers are infinitely nicer and more interesting than children brought up by servants. The names of these children were Marjory and Barbara and Kenneth, and they were as pleasant as their names. Marjory rolled a hoop, Barbara pretended to be an Indian, and Kenneth sat in a sort of infantile bath chair and talked to the birds, having but slight command of ordinary English. Elizabeth sat on a bench and impersonated, alternately, a buffalo and a white captive, neither of which roles was at all difficult. Her hands were in her lap and she gazed at the spring sky and the feathery trees. She was particularly contented and was enjoying a new sensation; she was looking prettier than ever before in her life, and she knew it!

For that strange thing, artistic setting, had transformed her, and though it might take an artist to have analyzed this, it didn’t require an artist to realize it, you see. Elizabeth had always been dressed by her mother, who had never been able to resist managing everything and everybody round her, and she had never observed that what had suited her in her youth didn’t suit her daughter today. If she had seen this daughter on her bench in Gramercy Park it would have dawned on her that she should have been sent to fancy-dress balls as Priscilla, the Puritan maiden, and not as a Persian princess. The prim little white collar, like a clergyman’s, the clean blue and white of the uniform — above all, the flat little English bonnet, which was nothing but a smooth bow spread over her smooth hair, framing her smooth forehead — all made her type jump out to you. The girl was charming.

Her hair came down in a sharp widow’s peak straight between her level brows; her eyes looked large and interesting. As an efficient New York beauty one wouldn’t have considered her, of course, but as a nurse in a park she was strongly arresting. She showed every inch of her breeding, every ounce of her education, every minute of the repressions of civilization that had fixed her type and personality. I tell you, she looked like the nurses Mr. Gibson and Mr. Christy draw on magazine covers; and you know as well as I do that men cut these out and frame them. Anyone would have turned to look at her.

It is very ironic that Mrs. Griswold could not know this, isn’t it?

At half past twelve they all went in to luncheon, and Elizabeth ate a chop and a baked potato and a large helping of string beans and two pieces of raisin bread, besides a dish of rice pudding with currant jelly and meringue on the top. While they took an hour’s nap she lay on a comfortable sofa and read a silly story in a magazine. There seemed to be no books of any particular cultural value about, and the doctor had to have plenty of magazines for his patients, for it is well known that you cannot be a doctor without magazines.

There was no tension in the house — nothing to live up to; that had all been transferred to headquarters. Elizabeth, though she did not know it, relaxed for very nearly the first time in her life. For culture, you understand, is quite as wearing as wage-earning If you go at it as seriously.

By quarter of three they were in the jolly, fenced-in little park again, and other children were playing with them. Barbara was a mermaid this time, and Miss Gizzle, as they called her, a shipwrecked mariner. Later she played a harp on her bench, while Barbara wallowed in the surf at her feet, to the great amusement of the young policeman who tramped round the park.

Dagmar called for them at five, and Elizabeth, her cheek moist from three sincere kisses, walked up Lexington Avenue to her studio, now a really useful room, changed her dress with all the thrill of a heroine in a melodrama, and hurried home.

“That’s a pretty frock, dear,” said Mr. Griswold at dinner; “pink becomes you.”

“I’ve worn it every night this week, papa,” she said, surprised.

The doctor examined the dress attentively, but he was not given to personalities.

The first day of the next week a slight accident occurred: Dagmar lost her park key. As you probably know, only the favored inhabitants of the borders of this park may enter it, and they have, each family, a key. Dagmar, much flustered, because she had heavy telephone duty that day, could offer no better suggestion than that someone should consult the policeman, who might know what to do; there was not a soul inside the iron fence, for it threatened rain, and they were very early.

“Very well,” said Elizabeth, and with her charges hanging to her skirts she went to meet the uniform that meant knowledge and protection.

“Have you a key to the park, officer?” she asked as he hastened his step a little to join her.

She did not notice the quick interest in his eyes; she was not in the habit of noticing policemen’s eyes. Are you?

She did not know, naturally, that her method of addressing this representative of the law was not at all the method of nursemaids in general. To her he was a servant of the city, paid to direct her to places she didn’t know, to clear the streets for her to cross, to keep from her eyes and ears things objectionable.

To him, as he looked down from his young tallness at the widow’s peak on her smooth forehead and listened to her clear, low voice, each word so perfectly cut from the others, she was simply the loveliest thing he had ever seen or heard.

“A key — into the park?” he repeated vaguely.

“Yes, yes — surely you or somebody must have one. We belong here,” she added hastily, “only our key is lost.”

“Oh, I’ve seen you here,” he said; “that’s all right. But — I don’t know — ”

He blushed violently through his freckled face up to his curly, sandy hair. He was fearfully embarrassed. Elizabeth, of course, could not know, but this was the first time he had ever been asked for the key, and he simply couldn’t remember, for the life of him, whether he ought to have one or not! He was clearly very much upset and she felt amused and sorry for him at the same time. Barbara pranced eagerly at her side.

“Let’s get in the first, Gizzle, the very first,” she begged.

“Look here,” he said abruptly; “I might just as well tell you as let you find out — I’m not very strong on this key business. I’m new here, you see, and if they told me about it I must have forgotten. Excuse me — I’ll look in my book.”

She waited, smiling, disarmed by this frankness, while he drew a little book out of his pocket and consulted it.

“It gets me,” he admitted at length; “I’ll have to call up and find out. I’m sorry — ”

“Oh, it doesn’t matter,” she said; “some of the nurses will soon come along and they can let us in. It was our fault, really.”

“But I’m supposed to help you out,” he insisted ruefully. “It doesn’t look as if I was much good, does it?”

He was quite young and so shy, evidently, that Elizabeth couldn’t resist laughing. Barbara laughed with her, and in a moment he was laughing too; and they all laughed together.

“You’re good-natured, anyway,” he said. For a moment she stiffened and stared slightly, then, with a sudden recollection, began to laugh again. Why shouldn’t a policeman be friendly with a nurse? This was part of the game. “Oh, well, why not be?” she answered; “it’s a lovely morning!”

“You’re right, it is!”

But he was looking at her and not at the morning; and she knew it.

Her spirits mounted; this was the nearest to an adventure that she had ever been in all her life. What would he have thought if he knew?

Dagmar was waving furiously; encumbered with Kenneth, she could neither leave him nor fly to the house.

“The other nurse wants to tell you something, doesn’t she?” he asked. “Shall I go and see?”

“Oh, no, I’ll go — just stay here with the children!” she cried, and flew across to the beckoning figure. Suppose Dagmar should call her Miss Griswold. That would spoil it all.

Dagmar had just remembered; the key was on the umbrella stand. Seizing the go-cart, Elizabeth piloted it halfway across the street, but only halfway, because the young officer ran to her aid.

“Let me take it,” he said, and pushed it carefully over.

They stood by the gate, waiting.

“They’re nice kiddies, aren’t they?” he muttered, still shy, but unwilling to yield to his shyness and go. “I like ‘em that age.”

“Yes; they’re very nice,” she replied, amused.

“I’ve noticed you before,” he volunteered; “you seemed kind to them. Some of the nurses — well, you can’t help wondering if the mothers know, that’s all.”

“I know,” she agreed gravely.

“Why don’t they take care of them themselves, anyway?” he blurted out, still staring at her.

Of course he couldn’t have known that she knew he was staring, she reasoned, so she looked the other way and let him. She didn’t know that she liked it, you see; she thought she was just not hurting his feelings!

“Why,” she explained thoughtfully, “I suppose they have other things to do, don’t you? Rich women, you know, don’t expect to take care of babies.”

“Oh! Rich women! Phew!” he burst out with a look of such disgust that she had to laugh again.

“Some of them are quite nice, really,” she hazarded.

“Not for mine!” he cried abruptly, and then as Dagmar approached, panting, with the key, he lifted his cap and walked away suddenly, very stiff in the back, as one remembering his high position and responsibility.

All that day the little encounter amused her in memory; she smiled, recalling his flushed, freckled embarrassment, his ingenious appeal to her mercy.

“He’s an awful nice p’liceman,” said Barbara; “but he oughtened to have forgottened his key, ought he?”

“He’s just beginning p’licing prob’ly,” suggested Marjory; and it occurred to Elizabeth that recruits must learn, somehow, somewhere, and that this was as good a place as any other to break them in.

The next morning he was at the gate as they came up.

“I’ve got it!” he cried boyishly, and held up a key. “The Cap. forgot to give it to me — what do you think of that?”

“Are you learning how to p’lice?” Marjory inquired with interest.

“I certainly am,” said he, strolling into the park. “You watch me police this park, now!”

They sat on the bench and he stalked stiff and straight round it, to the delight of all the other children.

As he drew up before them and saluted gravely, Barbara spoke: “You aren’t a blue policeman,” she announced; “why aren’t you blue?”

And Elizabeth realized suddenly that this was so; she had not noticed it.

“Because we’re sort of beginners,” he explained good-naturedly; “we aren’t fat enough for the blue uniforms, kiddie.”

“I s’pose they put you here because there’s only children, mostly?” said Marjory.

“That’s the idea.”

“What’s your name, p’liceman?” demanded Barbara.

“My name’s David,” said he. “I hope you like it?”

“Where were you before you came here?” Elizabeth asked. “What did you do?”

She spoke as she would have spoken to an interesting, well-mannered young guide or courier abroad. She forgot that he could not be expected to understand across what a gulf her interest stretched; that to him her kind young voice was only the voice of a kind young woman in a nurse’s uniform.

“Oh, I was on the rural police upstate,” he answered, flushing a little, “in Westchester County.”

“Oh yes,” she said, remembering the lean, olive-trousered men she had so often motored past; “those men round the aqueduct?”

“Yes,” he said simply; and she noticed that he didn’t say “yes ma’am” or even “yes, lady.” She liked it in him; of course those boys upstate must be of a very different class from the ordinary city policeman. That was why his voice was so pleasant and his manner only shy, only a little awkward — not common or impertinent. She remembered, suddenly, that one of her father’s uncles had been the sheriff of the little village where the Griswolds were born. And somehow this remembrance pleased her.

The girl did not realize, you must believe, with what unconscious expectation her days were filled after this. She did not realize that she came a little earlier each morning; that he entered the park as a matter of course and strolled about with her; that he waited at the gate; that he found the one open place at the north end and leaned, talking, against the iron spikes, while she sat, listening, on her bench, with Kenneth beside her.

One day, when it rained hard all day, she wondered why she was so restless, why the children tried her so, why a little paining shadow darkened everything inside her. Then, when it cleared suddenly, at half past four, she wondered again at the quickness of her shaking fingers as she pulled on their rubbers, for she was in too much of a hurry to wait for Dagmar.

“I can take them, Miss Griswold,” said the nursemaid; but she answered sharply, “No, indeed! The air will do us all good. Hurry, Marjory!”

As they entered the dripping park he swung over to them, slim flanked, with a long, young stride; why did Doctor Henderson’s short, nervous step patter through her mind?

A rubber poncho fell to his hips; he looked like some young officer on the stage.

“Oh! I never thought you’d come!” he cried; and a strange, crowded sensation pushed up round her — her — why, was that her heart? Why was she breathing so hard? Why should they laugh so, suddenly?

The sun poured out; the grass was emerald, diamond studded; the trees were full of birds. She glanced up at him, over the swinging rubber cape, and met his eyes full. They were blue eyes, and suddenly they turned into shining, piercing arrows that rained down, all fiery, into hers. It was blue and yet it was fire; it frightened her and yet it brought her peace; it threatened and yet it held.

You know, of course, what it was, but Elizabeth did not.

She knew, naturally, that people fell in love; she supposed they did it at a ball or in a gondola or while hearing beautiful music. Perhaps they looked up from some book of poems they were reading together. You see, she thought, poor child, that it was an idea — a something that attacked the mind. And of course it occurred between people of the same class.

So when he swung along beside her and looked at her — and looked at her — and her knees began to shake and that great wave rose and swelled in her side, the girl thought she was ill, and dropped, panting, on her bench; which was very damp, but she never knew it. He sat near her and it seemed to her that the side of her body next him belonged to some other person than herself—he was so near — so near —

They had not spoken. She glanced down at his hands; they were clenched on his knees. She wondered why.

“I — I never knew anybody like you,” he said, and his voice sounded husky and far away.

A lifetime of self-restraint came to help her.

“It — it cleared off, d-didn’t it?” she murmured.

He turned and seized her hands roughly; there was a wild, hot look in his eyes.

“Listen,” he said, “were you ever — fond of anybody — before?”

Then, at last, she knew. Then it burst on her. Her eyes darkened, and all the terrible, ridiculous, impossible future spread before her. Fond? Fond? She sprang up from the bench.

“You have made a mistake, I think!” she said. “Will you please go away now? Come, children!”

She never even saw which way he went.

That evening her father looked curiously at her.

“Haven’t you gained a little, Beth?” he said. “Is it that tonic?”

Mrs. Griswold also looked.

“She’s certainly improved amazingly,” she said thoughtfully. “Lou asked me what she was doing nowadays, to be so handsome.” She narrowed her eyes, and her daughter’s wavered and fell under hers.

The next day was Friday, and she stayed at home. The next was Saturday, and she bore it until four o’clock. Then she knew what had happened to her, and that she could not live so far from the park that was all the world to her. Something tore at her side and ached and cried there, and part of her lay on her bed and wept, and part of her sat on a bench and felt his hands. So that at five she crept out of her studio in her cap and cloak, and went, ashamed and secret, to watch him there — only to watch him, for she had no duty in the park that day.

She slipped through the gate as one of the last two nurses was leaving.

“The children have just gone in,” said this nurse carelessly; and “I know, I know,” Elizabeth said, and made for her bench, to weep there.

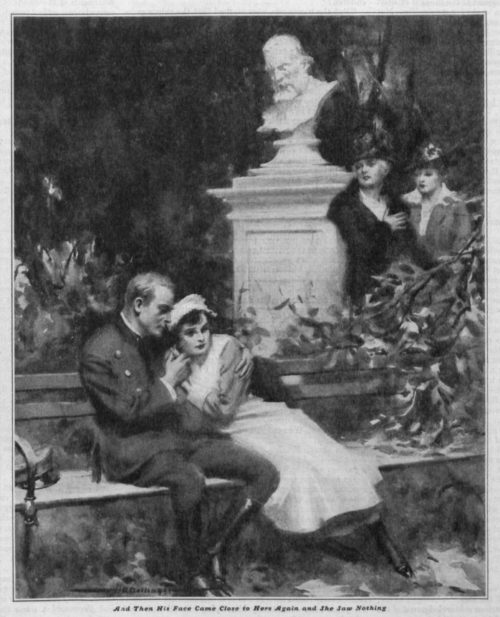

But he stalked in after her, and caught her in a grasp she had never known or dreamed of, and shook her a little and said, “I thought you’d never come!”

For a moment she saw the blue burning of his eyes, and then she saw nothing more, for he had kissed her.

Later she sat in his arms, in a great serene calm, and they talked.

“But you knew — you didn’t think that I didn’t mean for us to be married?” he said seriously. “You little darling, I’d never marry anybody in the world but you! There never was anybody like you! When I think of all the useless, silly, flirting fools — ”

“Perhaps you don’t know every kind of girl there is in the world,” she said, smiling adorably at him — oh, what would he say when he knew! — “but I will marry you, David dear; indeed I will. Don’t mind what anybody may say, ever. I tell you that I will.”

You see, all her culture counted at the last; and she knew that in the face of an enormous thing like this, nothing — nothing in the world — should separate them. Policeman or ambassador, a Griswold or a nursemaid, it was all the same. Nobody had ever told her that this kind of feeling existed, but now that she knew it she knew that every other feeling in the world is unimportant beside it. That strong, wonderful creature with his burning eyes was hers, and she was his. “You see, you’ve done something,” he repeated. “You amount to something. You’re a real person, you darling little Lizzie — you’re not just a dressed-up doll!”

“But — but you love me, anyway?” she begged. Oh, would he ever forgive her when he knew?

“Do I love you?” he laughed through all his freckles; “you wait till I can show you!”

And then his face came close to hers again and she saw nothing — not even her mother and her Cousin Lou, who could have touched her as she came out of the park.

Mrs. Griswold and her husband sat in a bitter silence in their motor. There was a heavy block on the avenue and they had to wait; something had broken down ahead.

“When can you see him, do you think?” said Mrs. Griswold. “Will you tell him that I am taking her away directly, and that under no circumstances can he even — ”

“Bessie, the girl’s twenty-five,” said her husband patiently; “I’m afraid you can’t really — ”

“Oh!” his wife cried, “please, please, Ben!”

“You’re sure you actually saw — ”

“Saw! Saw!” she echoed. “Great heavens; she was in his arms! He kissed her a dozen times! Saw!”

Her father winced.

“Don’t I tell you she doesn’t deny it for a moment? When I told her that the woman’s maid had told her mistress about it, and that she had had the decency to communicate directly with Lou, and that Lou and I went down to see for ourselves whether such a thing could be possible, and actually found them practically alone there, at that hour — what do you think she said? “

“I’m sure, my dear, I can’t tell.”

“‘We were engaged, mamma,’ she said; ‘wasn’t it all right?’”

Mr. Griswold sighed. He looked old.

“I’ll see him, dear; I’ll see him,” was all he said.

“And she has never buttoned her boots in her life!” cried Mrs. Griswold. “Oh, it’s too horrible!”

“I think she should have, then,” said Mr. Griswold shortly. “Look here, Bessie! Our girl would never marry a cad — I’m sure of that. I’d rather see her happy than grow up a sour old maid! There’s no doubt something can be got for the fellow to do — ”

“Oh! Oh, Ben! There he is! I see him!”

“What? Hush, Bessie, for heaven’s sake! Where are you looking?”

“There! In the club!”

In her confusion Mrs. Griswold had so far forgotten herself as to fix her eyes on a certain large window beside the pavement.

“Nonsense!” said her husband briefly.

“Ben, I tell you that was the man. And he had that very uniform on! A tall, sandy-haired, freckled fellow — very plain. Go up there and get him! Go now!”

“My dear girl, policemen don’t go into clubs. Not into the lounge, anyhow. I can’t — please, Bessie, don’t make a scene!”

“Then I’ll go myself,” said Mrs. Griswold simply.

“Oh, Lord — wait a minute,” he implored, for he believed she would do it. “Tell What’s-his-name to pull up on the corner, if this block ever breaks, and I’ll come there. At least I can get a drink.”

Harassed and gray, he wormed a way through the choked street and disappeared behind the great door. His wife sat, stony, in the motor, staring into the past. All that beautiful dainty girlhood, its perfection of detail, its costly foundations, laid through years — for what? A traffic policeman dashed through on a motor cycle, and she shuddered and cried a little, silently.

What could they do for him? Ben Griswold had a large professional income, it is true, but comparatively small investments; they lived furiously on what he made. Elizabeth and Cortwright had been their investments—and now Cort was driving a muddy truck somewhere in France, and Beth was engaged to marry a policeman! Such a quiet, steady girl — too quiet, her mother had secretly muttered in her heart.

They emerged from the block and waited in the side street among the club taxicabs.

“Extra! Extra!” yelled the newsboys. “United States on verge o’ war!”

Well, perhaps that would make a difference. If there should be war, people might forget sooner — but oh, how it cut her! How it cut!

The door slammed beside her.

“Get along home, Georges!” said Mr. Griswold. “I always forget Georges has gone. Well, Betsy, buck up, my dear; it might be worse.”

“Ben! It was the man!”

“Yes, my dear, it was. You have good eyes, if you are an old lady:”

“Ben! He — he was a — a — ”

“Oh, yes; he’s a policeman, all right. No doubt of that.”

“Ben! Does he admit — ”

“He came right up to me, my dear, and asked my permission to marry my daughter. He didn’t know who she was at all till this morning. He thought she was a nurse girl, it seems.”

“Oh! That ridiculous costume! But he knew perfectly—the idea! As if anyone could think Elizabeth was a nurse!”

“Well—I don’t know. It seems he did.”

“What was he doing — a man like that in that club?”

“He was drinking a Scotch and soda, my dear.”

“Ben! An ordinary policeman!”

“I shouldn’t exactly say that, Bessie. Not exactly. You see — oh, hang it all, Betsy, I can’t quite believe it myself, yet! Look here, dear. You remember when the commissioner swore in all those extra fellows to help out the police in case of riots or whatever — ”

“No.”

“Well, he did. He — he’s one of those.”

“Oh. Is it a better kind?”

“Oh, Lord, I suppose it is. Betsy, old lady, you certainly had a bad time. I — I felt it myself. But what could I do? You wouldn’t let me talk to her. I wonder what she’ll say?”

“Say? Ben Griswold, what do you mean?”

For his eyes were strange, his voice was shaky and sounded like the voice of the young man who had asked her to marry him 27 years ago, when she was 24.

“I mean when she sees this,” and he stuck his hand into his waistcoat and dropped a flash of white light into her lap.

It was of glass apparently, but blinding, and about the size of a five-cent piece.

“He seems very fond of her, Betsy. He says she’s the only girl he ever looked at; and, by George, I nearly believed him!”

“But, Ben — ”

“You never even asked his name, my dear.”

“But how — ”

“His name is Craigie — David Craigie.”

“N — not — Ben, it’s not the David Craigie?”

“I’m afraid it is, my dear. I wish he didn’t have quite so much, Bessie. It’s a pretty heavy responsibility, you know.”

She stared at him, stupid in the great revulsion.

“He said he got sick of signing checks all the time, and not doing anything; he’s a shy sort of chap, Bessie. He equipped an entire volunteer company up at that big place of theirs on the Hudson, you know, and still he couldn’t feel like anything useful, he said, so he went into the rural police volunteers up there and then joined the reserves here. He’s very quiet, you know— nobody knows him much.

“He told me he hated the sight of a girl till he saw Beth. Suspected ‘em all, I suppose. Sort of a serious chap — just the sort for her, I should say. Nothing very showy, but all there.”

“But, Ben — that old Mr. Craigie has — how much money has he, Ben?”

“A good deal more than anybody ought to have, my dear,” said her husband soberly; “somewhere round forty or fifty million, I’ve heard. We didn’t discuss it. He told me — young Craigie did — that Beth had found out somewhere how much a roundsman got a year, and explained to him how they would manage to live on it — twelve hundred, I think it was. He was thinking all the time that she thought it would be a rise in the world!

“And now,’ he says to me, ‘now I know what she was really thinking — my God, I love her more than ever, Mr. Griswold!’”

Mrs. Griswold was not listening, one fears. She was staring at the ridiculous shiny ring of white fire in her hand. Later, she cried a little and kissed her husband in the motor and he patted her shoulder. The last 24 hours had been hard for her, as you will understand.

So Elizabeth was married, in white satin, very plain indeed — to draw the eye to the great rope of pearls, her bridal gift from her husband. The biggest was about the size of a big white grape, and they ran down from that through moth balls to the little ones at the clasp, which were the size of peas. She looked very lovely and distinguished, and not at all tired; perhaps because she had refused to bother about anything, before the wedding, and passed most of her time in Gramercy Park. Marjory and Barbara were flower girls, and Kenneth sat in a front pew and talked with imaginary birds all through the service.

It is difficult to point a moral against foolish mothers from this story, for though Mrs. Griswold was undoubtedly foolish to have brought up her daughter to marry a multimillionaire, yet, you see, she did marry a multimillionaire. Which was, nevertheless, no credit to Mrs. Griswold, inasmuch as Elizabeth supposed herself to be about to marry a policeman!

After the wedding the reporters all rushed off to Mr. Craigie’s special car, which lay conspicuously in the Grand Central Station, en route for his Adirondack camp. A tall man and a lady in a thick veil climbed hastily into this car, and nobody dreamed that they were Mr. Craigie’s man and Mrs. Craigie’s maid.

And so, naturally enough, nobody dreamed of following the young couple to a modest but comfortable apartment overlooking Gramercy Park, which had been cleaned and polished to a state of supremacy by Dagmar, and vacated just before the wedding by the wondering Barbara and Marjory. Kenneth never wondered at anything.

They sat on a little balcony ringed round with geranium boxes and looked out over their park, sleeping in full white moonlight.

Will you laugh too much when I tell you that she wore a white cap and bib and apron, and that he was in the full uniform of the Police Reserve?

Of course you and I wouldn’t have done that on our wedding night, but they were not 25, either of them; and, though nobody knew it, they were a little romantic!

“I shall always love you in it,” she said, and kissed the buttons, which simply shows you how many extra kisses she had.

“And you really would have married me — you little wonderful thing?” he asked adoringly.

“Of course,” she said. “Of course, David. Weren’t you going to marry me?”

“Oh, but that was different,” he said, and kissed her again — but not her buttons.

And now I know you will laugh when I have to admit that over the nurse’s blue and white fell the milky, marvelous pearls that you must have seen in the photographs!

Because, you see, though she was romantic and though she had never been in love before, and though she had been perfectly ready to marry a policeman, she was only human after all!

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now