9 Fireworks Facts to Blow Your Mind

1. The color of a firework is determined by the elements present. Iron creates golden hues, Lithium produces red, and copper is used to achieve the elusive blue. Chemical compounds are combined with fuels and oxidizers to give a breathtaking splash of color in the sky that is really just idiosyncratic air pollution.

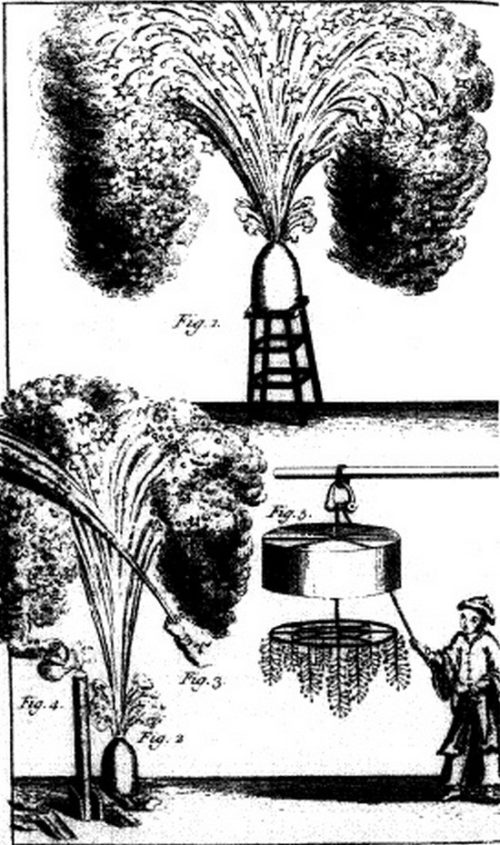

2. Unsurprisingly, the first fireworks were ignited in China between 600 and 900 A.D. These early pyrotechnics were bamboo shoots stuffed with saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur, and they were probably used to ward off evil spirits and bring good luck to the igniter. Although this ancient Chinese secret spread to the West in no time, China is still the world leader in production of fireworks.

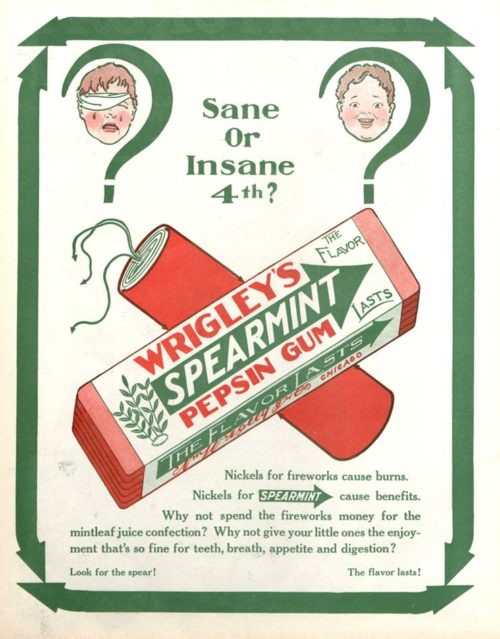

3. 2015 saw the most American firework-related injuries that resulted in emergency room visits so far in the new millennium – about 11,900. Only about one percent of those injuries were sustained by people 65 years old and up.

4. Sparklers can burn at 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. It is cute to use camera effects to spell a sentiment or draw a smiley with the things, but perhaps it would be wise to exercise discernment before handing a child what amounts to a blow torch.

5. Dogs and anxious people alike can take refuge in Delaware, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. These three states ban the sale of all consumer fireworks.

6. Fireworks are used to celebrate different holidays around the world. In the United Kingdom, Guy Fawkes Night is celebrated on November 5th with pyrotechnic shows. Bastille Day in France — July 14th — sees the Eiffel Tower illuminated with an explosive display as well.

7. The world’s largest fireworks display took place during a downpour. 810,904 fireworks were set off at New Year celebrations in Ciudad de Victoria Bocaue Bulacan, Philippines on January 1, 2016. This record is sure to change as soon as another location decides to take the title. Previous record-holders include Norway and Dubai.

8. Consumer fireworks have really taken off in the 21st Century. In weight, we’re blowing up more than double what we did in 2000: about 244 million pounds in 2016.

9. The first Independence Day in 1777 saw fireworks in Philadelphia and Boston. John Adams, in a letter to his wife in 1776, predicted that July 2nd would be a celebrated holiday, with “illuminations from one end of this continent to the other from this time forward forever more.” Although Adams was two days off, he was dead on in regards to nationwide “illuminations” that seem to grow brighter each year.

The Time the Johnsons’ House Caught Fire

When the Johnsons’ house caught fire — the second time that day — the entire neighborhood came to watch. The disquieting mass of black smoke that billowed from the top floor of the Tudor, with its gable roofs and timber framing, was a bleak beacon that summoned the residents of Birchwood Village to gather together. And gather together they did — a stray few at first, folks already on their constitutionals, after supper, around 7, on such an otherwise pleasant mid-April evening, curious as to what that rolling dark cloud was. Then, as word spread, and the suffocating dense smell of burnt, just burnt, blanketed the area, more and more people arrived, and more after that, and even more, and more still, until eventually nearly everyone had emptied from their homes, with screen doors smacking, light sweaters thrown on, stumbling into flip-flops and sneakers, jumping onto bikes, pushing baby strollers, pulling at yipping dogs on leashes, excited chattering, nervous murmuring. All of Birchwood Village turned out that day when the Johnsons’ house caught fire a second time.

The first question among the burgeoning group of looky-loos was whose house was it? because surely it couldn’t be the Johnsons’ house. Not again. Those poor Johnsons. Their house had already caught fire earlier in the afternoon, witnessed then by only a fraction of those who were streaming toward it now — mostly stay-at-home moms, and retirees, and a scattering of others who for whatever reasons had no particular place to be in the middle of the day, 2:30-ish. Of course no one wanted it to be the Johnsons’ house, not again, those poor Johnsons, but if it wasn’t the Johnsons’ house that was on fire, whose house was it, and did that mean there was a serial arsonist on the loose burning down houses one after the next?

Fortunately, although not so much for the Johnsons — in fact, it was downright unfortunate for the Johnsons — the house on fire was indeed the Johnsons’ and twice today of all things. Those poor, poor Johnsons. On the bright side, if there was one, as soon as the residents began to gather together, so too did the first responders — or would they be considered second responders under the circumstances, this being their second trip to the Johnsons’ house within the span of only hours? Three shiny red fire trucks from the nearby districts of St. Martins, Chester Hills, and Limerock burst onto the scene, along with a Metro ambulance, a Metro police cruiser, and police cruisers from the other nearby districts of Ridgeland and Rollingway. There was even some guy who came screeching up in a Jeep, narrowly avoiding the Thingstons’ empty recycling bin that they were always dilatory in retrieving from the curb, outfitted in what looked to be his very own firefighting gear — no doubt a volunteer who had heard the call on his scanner.

It quickly became quite an event, with the jumbled pattern of asynchronous flashing lights from the various vehicles, and the bustle and ruckus as the first responders — or were they second responders? — darted to their designated positions. Two burly firefighters lumbered down from the Limerock fire truck and went to work unspooling the thick yellow hose and connecting it to the hydrant that stood at attention at the intersection of Swan and Forest. That hydrant had been there for as long as anyone could remember, although no one could remember when it had been used last — most considered it merely decorative, akin to the flower beds at the four corners that sprouted blooms of fuchsia and deep purple — and yet here that hydrant was used twice today. A couple other firefighters grabbed the other end of the hose and ran off with it in the opposite direction, making a beeline for the Johnsons’ house. When the hose inflated, which Mary Ellen Pomeroy later complained had caused an alarming drop in the water pressure to her kitchen sink while she was doing the dishes, one especially brave firefighter, slight of build, wrestled with the nozzle to direct the powerful jet of water in the general vicinity of the volatile amalgam of bright orange and yellow and crimson flames that lapped away at the second story.

The neighbors stood in awe, mouths agape, hands on hips or chins, while the mission to save what remained of the Johnsons’ house proceeded with military precision. Some debated what part of the house that was, consumed by the blaze, wondering aloud if maybe it was the master bedroom as many of these older homes, and the Johnsons’ house was probably built in the ’40s like most of the other homes on the block, had their masters on the top floor. Others opined that it could have been the study for shelves crammed full of musty dusty books would most assuredly ignite as instantaneously as this fire had. And others questioned if the Johnson children were still young enough for a playroom and, if so, was that where it was — those poor Johnson children losing their playroom in such a jarring manner. Since none of those involved in the discussion had actually ever stepped inside the Johnsons’ house, the issue as to the specific location of the inferno therein, while intensely debated, ultimately remained unresolved.

Another, and not unrelated, topic of conversation, and one that should have properly been the primary concern, was where were the Johnsons anyway? There had been vague speculations but, as with the previous topic, no definitive conclusion. Ted Robinson, a DJ for the local public radio station who hosted a program of blues standards during the overnight shift from 11 to 3, postulated that Mr. Johnson, an attorney for a prominent personal injury firm who typically pulled late hours, was at work. Ted then tried to lighten the mood, as he was apt to do on his radio program according to those insomniacs and blues standards aficionados in the crowd who tuned in from time to time, by cracking a joke based on the premise that Mr. Johnson, like a lot of the lawyers in town, had his office in the tower on Market Street that many thought resembled a penis. But Mrs. Shuttleford, who did not suffer fools gladly and who, at age 88, prided in cutting her grass herself, and with a push mower, stopped Ted before he could reach the punch line, scolding that such bawdy humor was wholly inappropriate, with the whereabouts of the Johnsons largely unknown.

It was around then when one of the police officers, the police officer from Ridgeland who was contracted out by Birchwood Village to patrol the streets in his off-hours to curtail any shenanigans and suspicious activity and, of particular import, to make certain that members of the Wheelmen (and Wheelwomen) Cycling Club obeyed the traffic laws when they pedaled through the neighborhood on their weekend group rides, overhearing the conversation, interjected that everyone in the Johnson household was accounted for, having all absconded to Mrs. Johnson’s mother’s house in Butchertown after the first fire and not returned. With that bit of relief, Ted tried to retell his joke about the “irony” of lawyers working in an office tower that resembled a penis, but the moment had passed, and he gave it only a half-hearted attempt before sulking away to ready for his overnight shift — whatever that entailed, perhaps putting on a fresh shirt — playing blues standards from 11 to 3 on the local public radio station.

After 45 minutes, give or take as no one was minding the time, too engrossed by the hubbub, the firefighters appeared to have the fire well under control, save for some stray, dangling ribbons of soot curling and dribbling from the second-floor windows. The flames of bright orange and yellow and crimson had been extinguished and in their stead a soggy, dripping mess. Nonetheless, people continued to drop by, to have a peek, to see what was what, lingering about in front of the Johnsons’ house and on the lawns of the houses across from it. Young Billy Milner, an enterprising 10-year-old who already had his summer buzz cut even though school did not let out for the summer for another month, took advantage of the situation, as he lived in one of those houses across from the Johnsons’ where people were lingering, and set up a lemonade stand fashioned from a stack of TV trays he carried from his father’s rec room in the basement. Young Billy charged 50 cents for a Dixie cup of store-bought lemonade he precariously poured with two hands from a plastic gallon jug he snuck from the fridge. Mrs. Patterson, who lived next door to the Milners in a quaint Cape Code she shared with her ill-tempered — although some referred to the animal as simply plain hateful — Maltese, Koukla, mingled about with a platter of homemade chocolate chip cookies and a straw basket of her grandchildren’s leftover Easter candy, mainly loose jelly beans and malted milk eggs, which she offered gratis, and those were snatched up and gobbled down with haste.

Before long this gathering of concerned — if not concerned, certainly inquisitive — citizens escalated into a full-blown block party, even while the Johnsons’ house barely smoldered and the two burly firefighters had begun to respool their thick yellow hose and pack it away with the rest of their equipment. Beach chairs and blankets had been set about, people lounged and relaxed. A group of renters who shared a two-bedroom suite at the Stonemill Apartments at the end of Blanchard next to the park, with their shoulder-length hair and bushy beards and, observed Mrs. Shuttleford, “all sorts of tattoos — just everywhere,” showed up with their guitars and bongo drums and tambourines and staged an impromptu concert, singing songs no one had heard of, but no one seemed to mind either. Even Mrs. Shuttleford tapped her feet in rhythm. The starting lineup of the St. Martins Dragons, the reigning regional Little League champs, returning from practice at the field where the old Sears used to be, played games of run-down and pepper next to the Baxters’ white ranch that sat on the corner. A circle of college students, on a break from studying for finals, kicked around a hacky sack, and Old Man Williams brought out his bocce balls, and he never brought out his bocce balls before Memorial Day.

This kept on as the sun set and night approached. Gasoline generators were revved and throttled to power industrial-sized flood lamps so the firefighters could check for hot spots and structural instability. Cast in that harsh, artificial light, with shadows angled in jagged shapes, the Johnsons’ house was a shell of what it had been, a wooden cut-out backdrop from a movie set. One of the firefighters made his way into the attic and started cutting away at the roof with a chainsaw to ventilate the inside. The low dim humming of that chainsaw melted into white noise as attention to the Johnsons’ house waned. People had split and divided into groups and clusters to discuss sports and politics and current events, rumors and innuendo, to exchange business cards and recipes and the names and phone numbers of babysitters and handymen, to generally chuckle and guffaw and shoot the breeze.

Chip Caruthers, cradling his sleeping infant son, Chip Junior, tightly against his chest as he rocked slightly back and forth, to the requisite oohs and aahs of those he approached, including the police officer from Chester Hills, a stern individual who offered an uncharacteristic albeit heartfelt coochie-coochie-coo to the boy, remarked how this was better attended than the Fourth of July cookout held each summer on the grounds of the Birchwood Village Church. Everyone laughed and agreed because it was one of those funny comments that was also true. Then Tom Canari, the self-proclaimed “high roller” who would boast of frequenting the casino across the river for private games of baccarat cordoned off from the general public by a velour rope, added how “we should do this more often,” which was met with a very awkward and stilted silence until he clarified, “without the two fires to the Johnsons’ house of course.” Folks agreed, but the response was still tepid as no one much cared for Tom Canari as he was rather full of himself.

By about 10, the police cruisers and the ambulance and all but one of the fire trucks — the firefighters from Limerock lagging behind to keep an eye out for hot spots — had gone, as had most of the people. It was, after all, a weeknight. There were a few stragglers, those who for whatever reasons had no particular place to be and did not need to wake up early in the morning. A 20-something couple no one could place kissed passionately beneath the weeping willow in Mrs. Patterson’s yard, much to the consternation of her hateful Maltese, Koukla, who barked at them incessantly from inside the house through the living room window until Mrs. Patterson drew the shades. Some people planned to meet up sometime for lunch, or for cards, or just promised to “see ya around.” There was talk of bringing casseroles and salad and a cold-cut platter from the Kroger deli to the Johnsons, with an assortment of desserts — pies and cobblers and seasonal berries — and maybe some clothes and toys for their children as soon as it was ascertained how old their children were. In any event, all promised to check in on the Johnsons since that was the neighborly thing to do.

And at the end, everyone returned to their homes, and retreated silently inside, to do whatever it was they normally did when there wasn’t such a commotion, and Birchwood Village settled down once more, and everything went back to how it had been, except for the Johnsons, those poor Johnsons, the time their house caught fire, the second time that day.

News of the Week: McEnroe’s Comments, Martha the Dog, and the Man Who Predicted Selfies

Serena Williams vs. John McEnroe

John McEnroe is known for saying things. He used to be known for yelling things, but he’s quieter now, though probably no less opinionated.

During an interview with NPR about his new memoir, But Seriously, the 7-time Grand Slam Singles winner said that if 23-time Grand Slam Singles winner Serena Williams played with male tennis players, she probably wouldn’t be in the top 700. Of course, this is the part of the interview that everyone has latched onto — which is probably good for book sales — and it got a reaction from Serena herself on Twitter (where everyone releases official statements now, apparently).

Dear John, I adore and respect you but please please keep me out of your statements that are not factually based.

— Serena Williams (@serenawilliams) June 26, 2017

I've never played anyone ranked "there" nor do I have time. Respect me and my privacy as I'm trying to have a baby. Good day sir

— Serena Williams (@serenawilliams) June 26, 2017

Serena gets points for using the phrase “Good day, sir.” We need to use that more.

Now, to be fair to McEnroe, it’s not like he brought this up out of the blue to insult Serena. He simply said during the interview that Serena Williams was the best female tennis player of all-time (in fact, he has said that Serena is one of the best athletes in history, period), and the interviewer asked him why he had to say “female” and not just “best” including men. What an odd thing to ask. Men and women are different (I realized this the first time I went to the beach) and that also extends to professional sports, too. Why can’t we talk about how good or bad an athlete is by separating them into different categories when the very sports themselves separate them?

Even Serena (and it’s funny how we simply call her by her first name, that’s how iconic she is) said during an interview with David Letterman that she couldn’t beat a man, someone like Andy Murray, because the women’s game is different than the men’s game. Men are stronger and faster. So I don’t think we can say that McEnroe is “wrong,” and he certainly wasn’t being misogynistic.

I do take issue with the number 700 though. She wouldn’t have a chance against someone ranked so low that nobody knows who he is? With her serve and mental strength, I bet she’d be in the match.

And the World’s Ugliest Dog Is …

There seems to be two types of dogs that compete in the World’s Ugliest Dog contest in Petaluma, California, every year. They’re either big and slobbering or goofy or small and, well, rat-like. This year’s winner is Martha, a 3-year-old Neapolitan Mastiff that weighs 125 pounds and clearly falls into the former category.

Come on, she’s not really ugly, she’s just … droopy.

RIP Gabe Pressman, Michael Bond, and Michael Nyqvist

Gabe Pressman was a legend of New York news, starting out his six-decade career at several newspapers, including the Newark Evening Sun and New York World Telegram and Sun before moving on to a long TV career at WNBC in New York. Except for eight years in the 1970s where he worked for WNEW, he was with WNBC from 1956 until his death. The Emmy-winning journalist died last Friday at the age of 93.

Michael Bond was the author who created Paddington Bear. He also was the author of a series of novels featuring Detective Monsieuer Pamplemousse. Bond died earlier this week at the age of 91.

Michael Nyqvist was so good at playing the bad guy, in movies like Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol and John Wick. He also played the lead in the Swedish Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movies and appeared in a cool sci-fi ABC show a few years ago, Zero Hour, that really should have lasted longer. He died Tuesday at the age of 56.

World Asteroid Day

It’s funny how we go about our lives and hardly ever think about what’s going on in the skies above us. I don’t want to alarm anyone, but there’s a chance an asteroid could hit us.

Today is World Asteroid Day, which is a good day for scientists and world leaders to think about doing something about the problem. NASA actually has a Planetary Defense Coordination Office, which sounds like an organization from a sci-fi movie. Last December a NASA scientist warned that the world really isn’t 100 percent ready for an asteroid or comet hitting our planet, though we are getting better at it. It’s probably best not to think about it.

In related news, CBS’s Salvation, a new summer series about a group of scientists who band together to stop an asteroid from hitting the earth, premieres on July 12. Perhaps you’ve seen one of the 50,000 commercials for it that the network has been running every day for the past two months?

People Really Dig Salvador Dali

It doesn’t seem fair to have no control of your body after you die. There you are, in the ground resting, your life on Earth over and done with, and all of a sudden people are digging you up and bringing your body back to the surface so they can examine it.

That’s what’s happening to surrealist artist Salvador Dali, whose body is going to be exhumed by order of a Spanish judge to settle a paternity suit brought by a woman who claims to be his daughter. The woman says that Dali had an affair with her mother, who worked as a nanny near Dali’s home.

Dali’s estate is worth hundreds of millions of dollars, but the woman says it isn’t about the money, it’s about finding out who she is and revealing the truth for her mother.

The Best Game Shows of All-Time

Well, look at this: an internet list that isn’t terrible.

Newsday has picked the 25 best game show of all-time, and it’s really a well-balanced list. Yes, I could argue — and I will argue — that shows like Love Connection, Deal or No Deal, and The Dating Game don’t deserve to be on any kind of best game show list, I’m impressed that most of the list is taken up by truly great, classic shows like The Price Is Right, To Tell The Truth, Password, The $64,000 Question, Jeopardy, Wheel of Fortune, and What’s My Line?

To replace the shows that shouldn’t be on the list I’d probably add Remote Control, Tic Tac Dough, Truth or Consequences, Scrabble, maybe Blockbusters, and how about Battle of the Network Stars, which came back to ABC last night?

We need more game shows on television. Just get rid of talk shows like The View and celebrity shows like Access Hollywood and they’ll be plenty of room.

Charles Schulz Predicted Selfies

The frequent Saturday Evening Post contributor was ahead of his time in many ways, including when it comes to picture-taking.

https://twitter.com/Peanuts_comics/status/878993191705296896

This Week in History: Jack Dempsey Born (June 24, 1895)

The world heavyweight champion boxer actually wrote an article for the August 29, 1931, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, on what happened behind the scenes before his losing battle with Gene Tunney.

This Week in History: Korean War Begins (June 25, 1950)

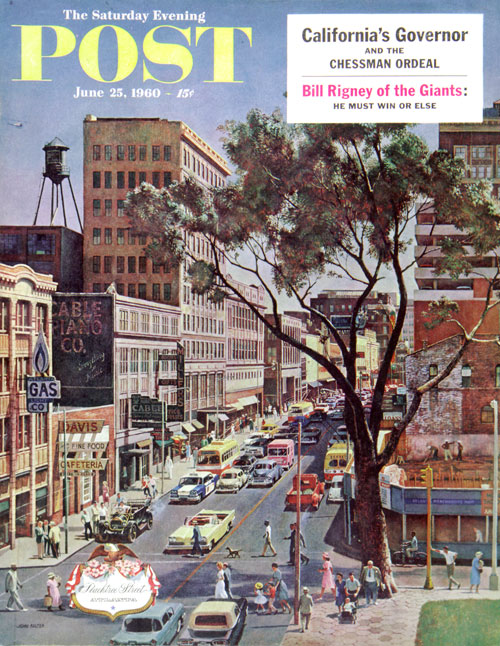

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: “Peachtree Street” by John Falter (June 25, 1960)

John Falter

June 25, 1960

If I wasn’t a writer I’d want to be an artist or cartoonist, but I don’t have the skill for it. Even my stick figures look kinda funny. I mean, I can’t even begin to understand how John Falter created the way that he created, the mix of color and shadow, the way he gets the perspective right. There’s so much going on in this picture, so many places to look and explore, that it’s rather mesmerizing.

July Is National Ice Cream Month

With that Falter cover you know that I have to link to a recipe for peach ice cream, right? It’s from Southern Living and it’s officially called Summertime Peach Ice Cream. It looks easy to make too, just evaporated milk, condensed milk, half and half, sugar, and vanilla instant pudding mix.

Oh, and peaches. Don’t forget the peaches.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

International Joke Day (July 1)

Here’s my favorite joke:

Knock-knock

Who’s there?

Interrupting cow.

Interrupting co …

MOOOOOOOOO

Wimbledon Begins (July 3)

Because she’s pregnant, Serena won’t be able to play the 700th man in the world or anyone else, but McEnroe will be one of the commentators when the tennis tournament kicks off on Monday, a week later than usual. You can watch the action live on ESPN (and on tape on Tennis Channel at night).

Independence Day (July 4)

In between the eating of burgers and the watching of fireworks, take a look at this collection of classic Saturday Evening Post covers that celebrate the day.

Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Films Directed by Women

Award-winning film critic and writer Bill Newcott has been covering Hollywood for more than 40 years. He is the creator of AARP’s Movies For Grownups franchise and the movie critic for The Saturday Evening Post.

Saturday Evening Post movie critic Bill Newcott reviews several of the nine new movies directed by women, including Wonder Woman, Paris Can Wait, The Beguiled and Maudie. Plus, he looks at new DVD and Blu-ray releases of three classics: Michael Caine’s A Shock to The System, Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth, and Bob Hope’s visits with U.S. troops overseas.

Listen to all of Bill’s podcasts.

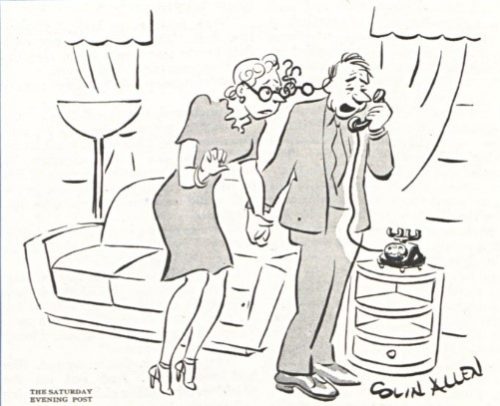

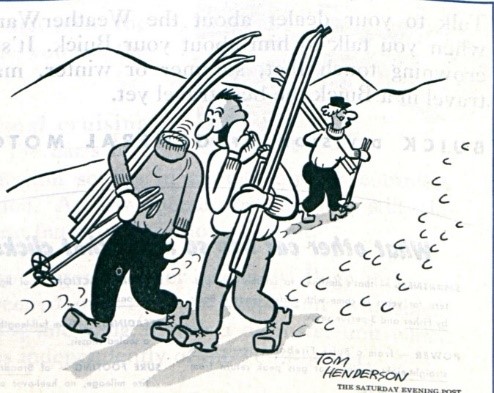

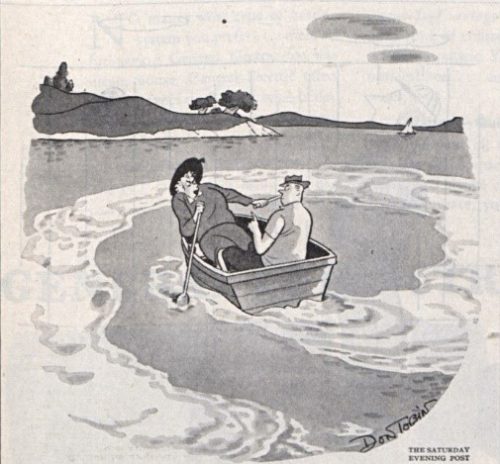

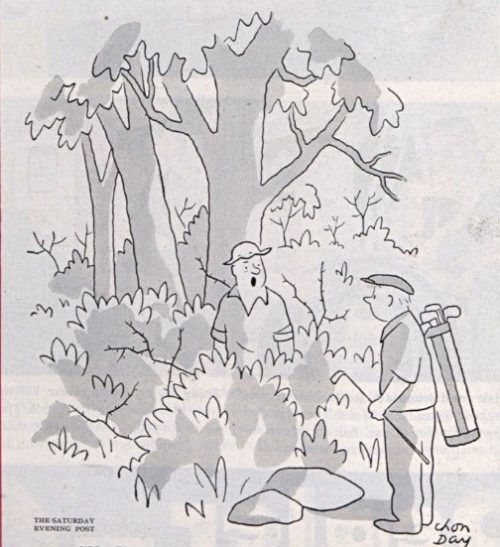

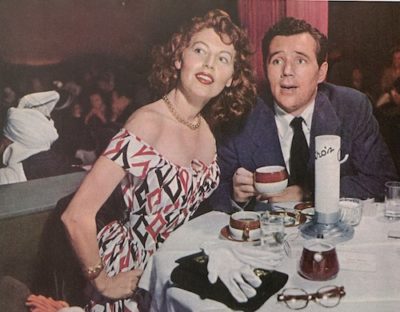

Cartoons: Dynamic Duos

In life, some people are paired perfectly!

January 26, 1946

December 7, 1946

June 7, 1947

June 26, 1948

June 26, 1948

May 7, 1949

November 14, 1959

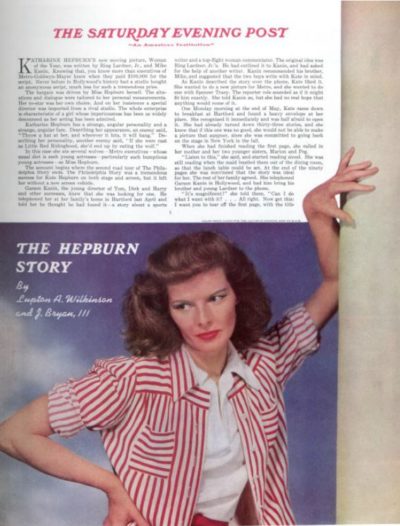

Katherine Hepburn Storms Hollywood

Originally published December 13, 1941.

When David O. Selznick, RKO’s chief of production, and George Cukor, director of A Bill of Divorcement, first approached a then-unknown Katharine Hepburn to appear in the film, they offered her $500 a week. Kate replied coolly that she “would prefer $1,500.”

At the end of two weeks, Selznick had come up to $1,250 a week. Kate asked her family whether they thought she should trim her sails a bit. Her mother said she’d be insane not to. Her father said she shouldn’t. So she told casting agent Leland Hayward, “I said $1,500 a week.” Selznick told Hayward, “I like her, but she’s got no right to demand $1,500. I won’t meet any such figure. That’s final!” Hayward knew that Selznick meant what he said. But by this time he also knew Kate. “She’ll never give in,” he told Selznick, “but look here: In the theater she’s used to rehearsing free, and she’s green. I’ll tell her you’ll meet the $1,500 figure for four weeks, but that she’ll have to give you a rehearsal week free. That’s the equivalent of five weeks at $1,200.” Selznick said at once, “I’ll do it.”

Today both he and Kate regard the deal as the triumph of their lives. Selznick got a leading woman for $6,000. Kate set a per-week rate that was not far from the very top of the payroll. And neither had given in.

When she arrived in California, Hayward and his partner, Myron Selznick, met her train at Pasadena. They will never forget the sight. One of Kate’s eyes was swollen shut from an injury she’d suffered on the ride. The other was inflamed sympathetically. Her freckles seemed as big as potato chips. She was wearing a bizarre blue suit and a pancake straw hat that in 1941 might be called “stylishly insane” but in 1932 was merely insane.

“My God,” Selznick whispered to Hayward. “Did we stick David $1,500 for that?”

The agents delivered her to David Selznick in silence and disappeared. Selznick, too, took a single look, then stepped into the next office and phoned Cukor. “Your star is here, George. I’ll send her down.”

Cukor had a sheaf of dress designs spread out. Still “busy being superior,” Kate leafed through them contemptuously. Her only comment was, “Not quite the sort of thing a well-bred English girl would wear, I’m afraid.”

“No?” said Cukor. “And what do you think of what you’re wearing now?”

“I think it’s very smart,” she said.

“Well, I think it stinks,” he retorted.

Cukor has described Kate’s mood, during her first Hollywood phase, as “sub-collegiate idiotic.” The incident of the dress designs was his first clue.

In her first meeting with RKO’s press department, she announced, “Publicity? Not for me — none at all!” She wanted to wait until she knew whether she deserved it, and she remembered her father’s creed: “Do your work. Keep out of the papers. Your private life’s your own.”

Having alienated the RKO press department before noon on her first day, she looked around for more trouble. She found it quickly. A studio photographer had taken some stills of her with co-stars John Barrymore and Billie Burke. An RKO official sent prints of the pictures for the three stars to autograph as souvenirs for visitors. Kate told Cukor haughtily, “I never give autographs.”

Cukor handed the stills back to the messenger. Then he turned to Kate. “You! Do you really think anyone would want your autograph alongside Barrymore’s and Miss Burke’s? Those two are actors! If you study for 25 years, maybe your signature will be worthy to go with theirs.”

That hit home. Afterward, Kate was humble toward acting. Her supercilious attitude toward Hollywood fell away. She flung herself into the 10-hour-a-day schedule with all her intensity. From the first moment she appeared on screen, Cukor saw in her something fine, and he maneuvered with skill and patience to evoke it.

Barrymore helped her develop her talent further. They also developed a friendly repertoire. One day he stared at her until she squirmed.

“What’s that for?” she asked.

“Isn’t it the customary thing to stare at beautiful young girls?”

Kate wouldn’t accept the explanation.

“Well,” said Barrymore, “I was just thinking how much you reminded me of my second wife.”

Kate smiled.

“Or was it my third?”

To his delight, Kate swore right back at him.

Barrymore says, “I remember every hour of working with her. … Miss Hepburn’s talent was so clearly perceptible, and she was so intelligent in learning, that working with her was all pleasure. But Lord, she was innocent!”

Without ever having seen the picture, she and her husband sailed for Europe. They were still there when A Bill of Divorcement was released. It was an instant success.

RKO’s urgent cables finally caught up with her in Vienna. They wanted her to return at once. Kate agreed and sailed for home. Reporters swarmed aboard her ship at Quarantine. Kate’s back went up at once. Even more unfortunate was the interview that RKO forced her to give a group of fan-magazine writers. She might better have kept silent, but “they asked a lot of asinine questions, so I gave them asinine answers.”

“Are you married?” they asked.

“I don’t remember,” she said.

“Have you any children?”

“Yes, two white and three colored.”

“How does it feel to be a socialite in Hollywood?”

That was the last straw. White with fury, she strode from the room.

Cover Gallery: Celebrating America

These Post covers and illustrations honor the land of the free and the home of the brave. Happy Independence Day!

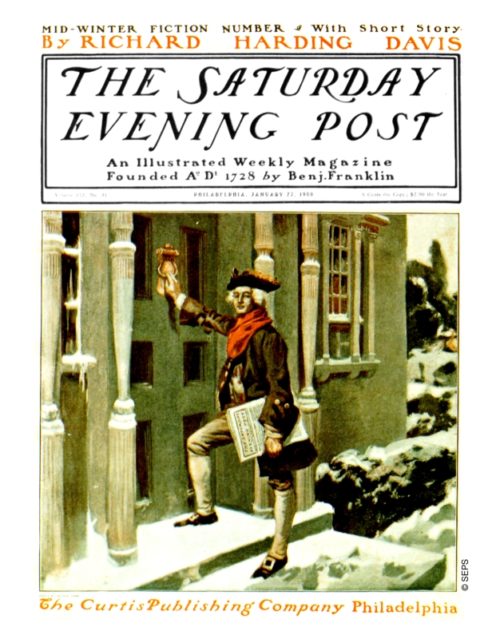

George Gibbs

January 27, 1900

George Gibbs painted over 40 covers for the Post during the first decade of the 20th century. He was a competent illustrator who could depict romanticized historical scenes and subjects to the taste of editor George Horace Lorimer.

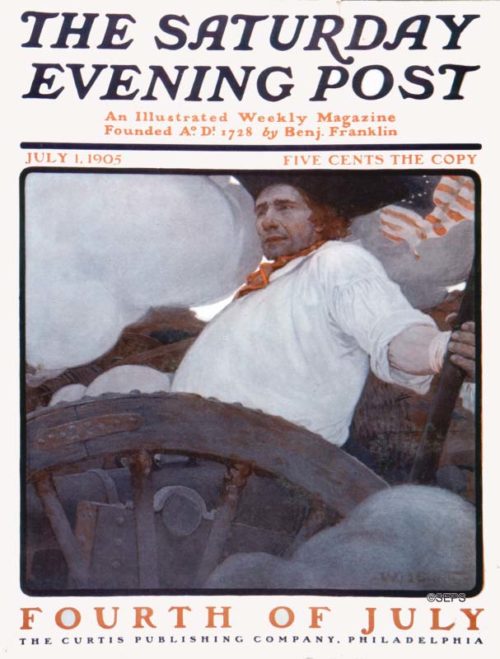

Walter H. Everett

July 1, 1905

Walter H. Everett created covers for the Post during a time when war dominated the magazine. Many of his covers feature soldiers and pirates and occasionally a beautiful woman.

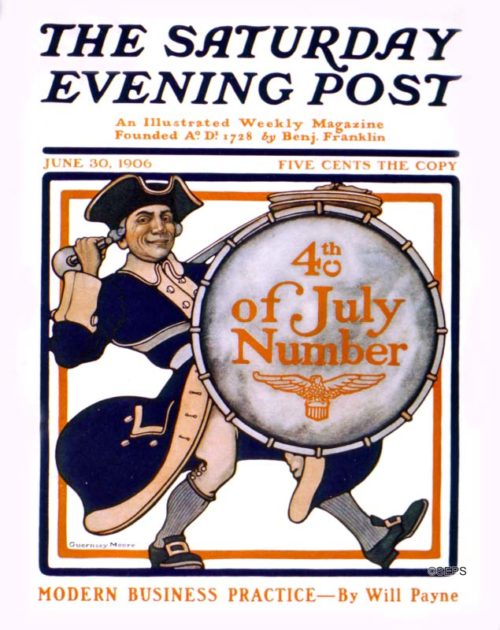

Guernsey Moore

June 30, 1906

Guernsey Moore illustrated the first colored cover for the Saturday Evening Post. In 1900, he illustrated new lettering for the Post’s masthead and in 1904 became the art editor of the magazine.

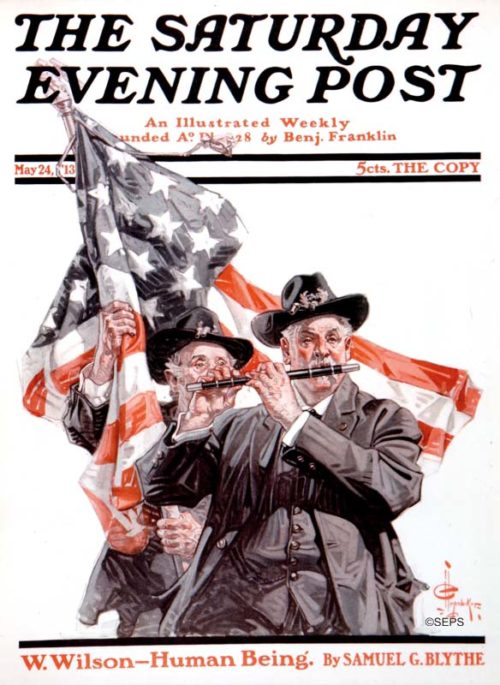

J.C. Leyendecker

May 24, 1913

J.C. Leyendecker was only one of the four major artists from the first decade to continue illustrating Post covers after 1910. Over the course of the next decade, Leyendecker painted well over 100 covers for the magazine, including these patriotic Civil War veterans in 1913.

J.C. Leyendecker

July 6, 1918

For several years, war influenced the covers of the Saturday Evening Post, and many were painted by J.C. Leyendecker. This 1918 cover of a colonial drummer was painted by Leyendecker despite his anti-war views, which he got to express with his famous New Year’s babies.

J.C. Leyendecker

July 5, 1919

J.C. Leyendecker experimented with a variety of subjects and attitudes, but his most noteworthy work marked and celebrated America’s holidays. He painted covers for several holidays from 1910-1919 and some, like the Fourth of July and the New Year, belonged to him almost exclusively.

Ellen Pyle

July 1, 1922

This 1922 cover was created by one of the Post’s most well-known female artists, Ellen Pyle. Known for painting children and beautiful young women with a goal of capturing the “unaffected natural American type,” Pyle’s four children became models in most of her covers.

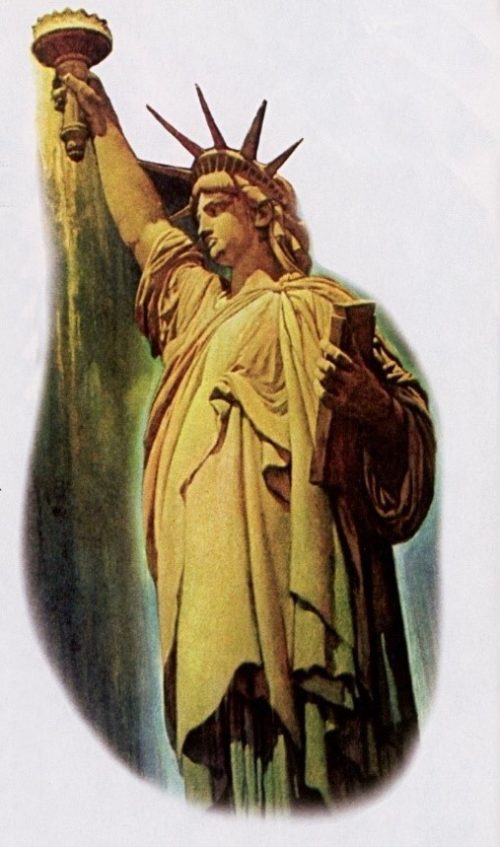

Norman Rockwell

October 11, 1941

This Norman Rockwell Statue of Liberty is part of a more detailed illustration with Lady Liberty shooting from the sky like a meteor as onlookers watch from below.

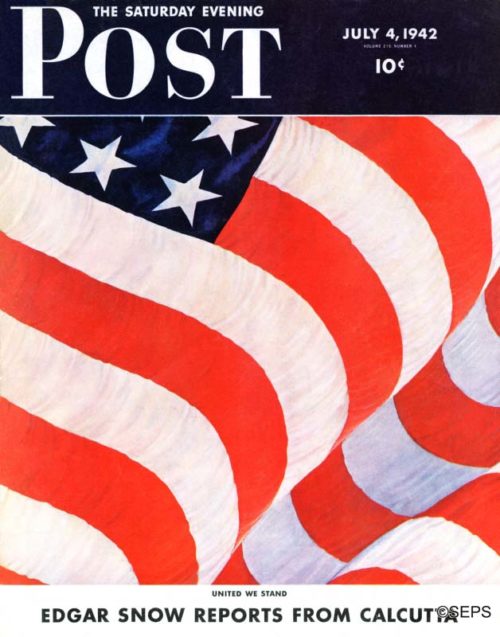

John Clymer

July 4, 1942

John Clymer created 80 Saturday Evening Post covers from 1942-1962. He often painted patriotic scenes covering vast landscapes, making this close-up of the American flag something unique.

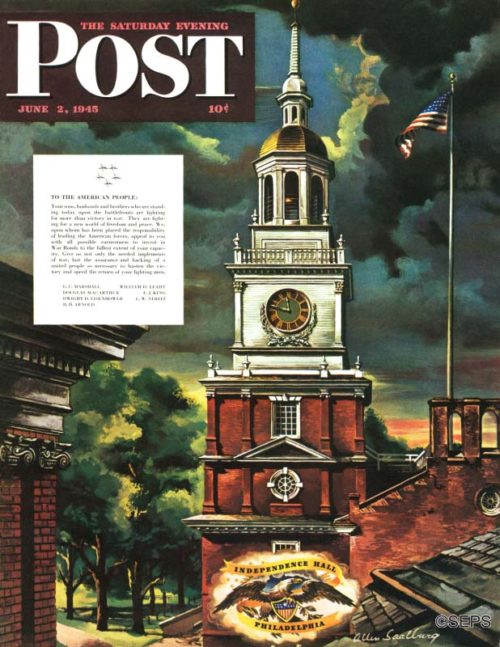

Allen Saalburg

June 2, 1945

In 1945, Independence Hall was just across the way from the Post offices, and, more than any other structure, it is a symbol of American perseverance and love of liberty. Saalburg’s painting is a view of Independence Hall looking west. The building at the left is The American Philosophical Society. The Post‘s offices were directly behind the trees in the left foreground.

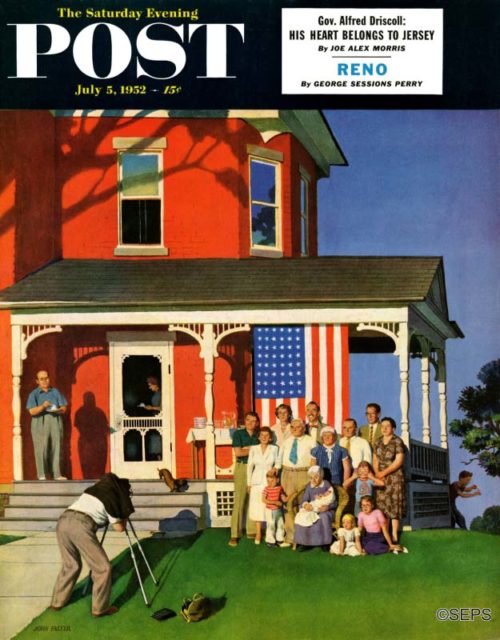

John Falter

July 5, 1952

John Falter painted more than 120 covers for the Post. He loved to illustrate Midwestern Americana, which he perfectly captures in this idealized family reunion scene. After the Post started using photographs rather that illustrations on its covers, Falter turned to portrait painting and book illustration. Many of those had a patriotic bent as well: he illustrated a special edition of Carl Sandburg’s Abraham Lincoln – The Prairie Years and Houghton-Mifflin’s Mark Twain series.

North Country Girl: Chapter 6 — A Very Ratty First Communion

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

For my semi-devout Catholic father’s sake, my skeptic mother gamely took meat off the menu for our own Friday dinners, which I made a trial for her, as I couldn’t stand cheese or eggs or fish. Pancakes were my Friday dinner of choice.

Eating meat on Friday was a mortal sin, as I learned in my catechism class, which I had to attend every Wednesday afternoon, along with a handful of other Catholic kids who didn’t go to parochial school. The class was held at Holy Rosary School, where frightening nuns in full habit prepared us to make our First Communion by drilling us with the Baltimore Catechism. We went over and over questions such as “Why did God make you?” until we could parrot the word-perfect answer: “God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him forever in the next.”

The nuns hated everyone in the catechism class. We were practically heathens; good Catholic children went to parochial school. The nuns assured me that I was not going to heaven as I did not have a saint’s name, and that my mother wasn’t going to meet St. Peter either, as she wasn’t Catholic. I was pitched into existential despair by this knowledge. It was also bone-chilling to have to make my first confession, required before taking communion. I had to learn yet another series of correct responses to questions I didn’t understand before I could enter the dark, velvet-curtained booth to make my confession. I knelt in the dim light until I heard the swoosh of the screen sliding back; even then the priest’s face was blurred through wavy plastic panels that were punctuated with holes so we could hear each other. I had to confess my sins, sins that I pretty much made up. I was seven years old. I didn’t steal, I didn’t lie, I didn’t take the Lord’s name in vain. I mostly did exactly as I was told. Did fighting with my sister count?

Having gotten that horrible ordeal over, I made my First Communion on a gloomy, rainy April Sunday, wearing a frilly white dress and a dainty veil bobby-pinned to my head, like a tiny bride. My Catholic grandmother made a big fuss over me, and gave me a small white missal with brightly colored illustrations of gospel scenes, and a pink and gold watch.

After that endless mass (dozens of little communicants lined up at the rail, all of us terrified lest we drop the Host out of our mouth and onto the floor, which according to the nuns, went so beyond a mortal sin that death by lightning was to be expected), our family went to breakfast at Perkin’s Pancake House, a huge treat, as it was always jam-packed on Sundays, and my father hated to wait for a table anywhere. Because I had to fast for two hours before taking communion, I was starving. Alas, the chocolate chip pancakes I always craved were still forbidden, even on the occasion of my First Communion; not by the Church but by my dentist dad who viewed them as candy for breakfast.

When we came back to our house, our happy, blessed party was greeted with a rat infestation. Duluth is a port city, built on a hill, and snowmelt and steady rains must have driven the rats up from the lake all the way to our “nice” neighborhood. My most vivid recollection of that day is not receiving the body of Christ for the first time, but watching my grandfather, the great hunter, beat a rat to death with a shovel. Poison was set out, and for the next few weeks I had to check carefully when I went down into my dad’s basement workroom to play with my Creepy Crawler set to make sure I didn’t step on a dead rat.

I loved my Creepy Crawler set; I squeezed bottles of red or blue or green liquid plastic into metal molds in the shape of insects, and then inserted the molds into a heater to set them. There was a flimsy wire handle to remove the red-hot molds, and a prescribed time to wait before peeling your new insects out of them, but burnt fingers inevitably ensued. To my great joy, my sister Lani was expressly prohibited from playing with my Creepy Crawler, or even being in the workroom while I used it.

Toys were plentiful, arriving as birthday presents and from Santa. Each December brought the thrill of new toys from Mattel and Hasbro. The commercials on TV and the photos in the Sears catalog made each doll and toy look irresistible, promising hours of fun. My mother long resisted getting me a Barbie; she thought there was plenty of time for girls to be clothes-obsessed, starting at age twelve. And every Barbie outfit came with the dreaded little pieces, accessories of tiny shoes and jewelry.

When Santa finally brought me one, a blond bubble-hair doll with a wasp waist and deformed feet, arched so high that the Barbie mules did fall off and get lost immediately, a girl about my age moved in across the street (only to move away a few months later). She also loved to “play Barbies,” which did indeed involve nothing other than making up reasons why our Barbies needed to change clothes every few minutes. I eventually acquired a Ken, who was boring, and a cardboard Barbie House, that my hung-over, fumbling, grumbling dad put together for me on Christmas morning. I never got the pink Barbie convertible the girl across the street had that I was consumed with desire for and would have pilfered if given the chance. Then I would have something to confess.

I never got the cotton candy machine or the snow cone maker I begged Santa for, in letters and in person, year after year. I did get the much-lusted after E-Z Bake Oven, but after I had used up the two boxes of cake mix and the one box of brownie mix that came with it (cakes and brownies that came out medium rare), I had nothing left to bake with. It never occurred to me that I could just use part of a box of grocery store cake mix. I thought because I had a miniature oven, I needed miniature boxes of mix.

Board games seem to have been thoughtfully distributed among my friends. Judy Lindberg had Operation, which my mother refused to buy, certain I would immediately lose the pieces. To prove her wrong, I actually managed to hold on to all of the components of Mouse Trap, which was much more fun, for years. I also had Lie Detector, where you had to determine the guilty party among twenty or so suspects. I played this over and over until I learned to figure out who dun it within three guesses, which happened about the same time the batteries died, and since we never had batteries in the house, that was the end of that game. Nancy Green had Mystery Date and Careers, which let us pretend we were teenagers or adults. Those games taught me to judge boys based on their looks and that secretary was a good job. My one Congdon school pal, Nancy Erman, had The Game of Life, which I adored. So much better than slow, stodgy, unwinnable Monopoly, with useless Water Works and endless passings of Go. Life had the little cars which you filled up with your peg husband and children. Then there was the heartbreaking decision you had to make, almost at the beginning of the game, to go to college or to start working and making money. We should have figured out then that The Game of Life was rigged.

My deal with Nancy was that we would have one game of Life and then play trolls. She had at least a dozen troll dolls, in various sizes: homely, grinning, sexless, squat figures with long, neon-colored hair. I only had a few, as I had to buy mine with my own money. My mother, the toy tsar, refused to pay for anything so ugly.

When I was seven I set my heart on a Chatty Cathy, the star of seemingly every pre-Christmas toy commercials. Chatty Cathy was the most marvelous doll ever. She talked! You had to pull a string on the back of her neck to make her speak, and then she only said about five things. I was desperate for her. On Christmas morning Chatty Cathy was perched under the tree, reinforcing my belief in Santa Claus despite Nancy Green’s best efforts.

That was the year that we took an odd vacation to St. Petersburg, Florida, with the Lindburgs. Our family drove down, they flew; a week later they drove back in our car and we flew home. I have no idea whether it was to save money or see the country. I only have two memories of the car trip down: driving past an ancient kerchiefed black woman sweeping a dirt yard with a broom made of sticks, and my dad, pushed beyond human endurance by hearing “My name is Chatty Cathy” for the eight thousandth time, flinging my new doll out the car window somewhere in Alabama.

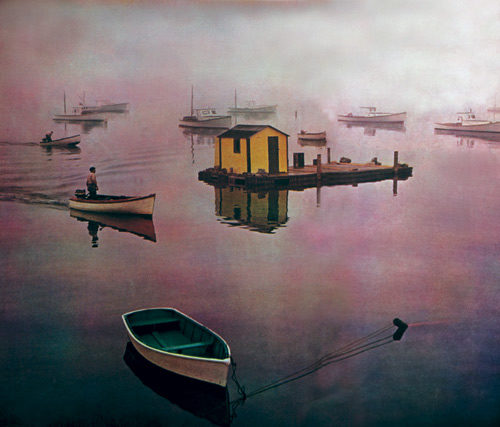

The Lobsterman’s Commute

Each dawn the shores of down-East Maine awake to the hollow “pip-pip” of the outboards and the “crump-crump” of the inboards as the lobstermen start making their rounds of the bays, inlets, and off-shore shallows to collect the day’s catch.

It is this misty interregnum between night and day, sleeping and waking, the past and the present — that dismal interval known to newspapermen as the “lobster trick” — that the photographer has caught, with the delicate immobility of a fossil print, at Prospect Harbor, Hancock County, Maine. The time is 5:30 of a midsummer morning, and the lobstermen you see are using their skiffs to ferry out to their larger lobster boats.

Maine water is cold, Maine lobsters — together with those of the neighboring Canadian Maritime Provinces — are the best in the world, and this picture is what a Maine lobsterman, stroking his chin, would call a “cocker.”

—“Lobster Trick,” Face of America, July 16, 1960

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

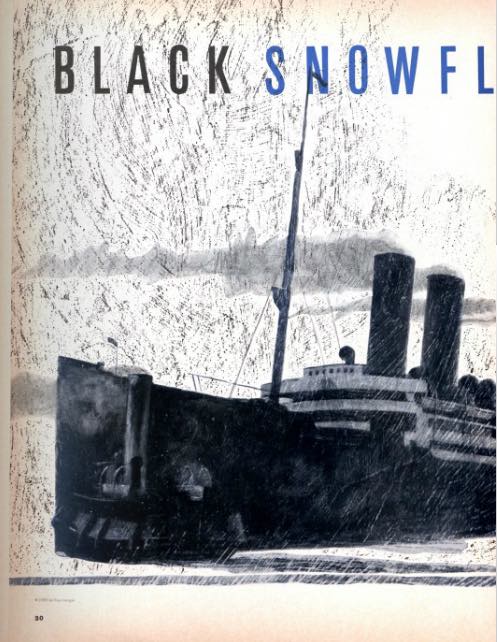

“Black Snowflakes” by Paul Horgan

“Richard, Richard,” they said to me often in my childhood, “when will you begin to see things as they are?”

But I always learned from one thing what another was, and it was that way when we all went from Dorchester to New York to see my grandfather off for Europe, the year before the First World War broke out.

He was a German — my mother’s father — and it was his habit, all during the long time he lived in Dorchester, New York, to return to Germany for a visit every year or two. I was fearful of him, for he was large, splendidly formal in his dress and majestic in his manner, and yet I loved him for he made me know that he believed me someone worthwhile. I was ten years old, and I could imagine being like him myself someday, with glossy white hair swept back from a broad, pale brow, and white eyebrows above China-blue eyes, and rosy cheeks, a fine sweeping moustache and a well-trimmed white beard that came to a point. He sometimes wore eyeglasses with thin gold rims, and I used to put them on and take them off in secret. I suppose I had no real idea of what he was like.

There was something in the air about going to New York to see him off that troubled me. I did not want to go.

“Why not, my darling?” my mother asked as I was going to bed the night before we were to leave home. Before going down to dinner, she always came in to see me, to kiss me good night, to glance about my room with her air of giving charm to all that she saw, and to whisper a prayer with me that God would keep us.

“I don’t want to leave Anna.”

“What a silly boy. Anna will be here when we get back, doing the laundry in the basement or making Apfelkuchen, just as she always does. And while we are gone, she will have a little vacation. Won’t that be nice for her? You must not be selfish.”

“I don’t want to leave Mr. Schmitt and Ted.” Mr. Schmitt was the iceman, and Ted was his horse.

My mother made a little breath of comic exasperation, looking upward for a second. “You really are killing,” she said in the racy slang of the time. “Why should you mind leaving them for a few days? What is so precious about Mr. Schmitt and Ted? They only come down our street twice a week.”

“They’re friends of mine.”

“Ah. Then I understand. We all hate to leave our friends. Well, my darling, they will be here when we get back. Don’t you want to see Grosspa take the great ship? You can even go on board to say good-bye. You have no idea how huge those ships are, and how fine.”

“Why can’t I go the next time he sails for Germany?”

At this my mother’s eyes began to shine with a new light, and I thought she might be about to cry, but she was also smiling. She gave me a hug. “This time we must all go, Richard. If we love him, we must go. Now people are coming for dinner, and your father is waiting downstairs. Now sleep. You will love the train, as you always do. And in New York you can buy a little present for each one of your friends.”

It was a lustrous thought to leave with me as she went, making a silky rustle with her long dress. I lay awake thinking of each of my friends, planning my gifts.

Anna, our servant, was a large, gray, Bohemian woman who came to us four days a week. I spent much time in the kitchen or the basement laundry listening to her rambling stories of life on the “East Side” of town. She had a coarse face with deep pockmarks. I asked her about them one day, and she replied with the dread word, “Smallpox.”

“They thought I was going to die,” she said. “They thought I was dead.”

“What is it like to be dead, Anna?”

“Oh, dear saints, who can tell that who is alive?”

It was all I could find out, but the question was often with me. Sometimes in the afternoon, when I was supposed to be taking my nap, I would hear Anna singing, way below in the laundry, and her voice was like something hooting up the chimney. What should I buy for Anna in New York?

And for Mr. Schmitt, the iceman. He was a heavy-waisted German-American with a face wider at the bottom than at the top, and when he walked he had to swing his huge belly from side to side to make room for his steps. He had a big, hard voice, and we could hear him coming blocks away, calling, “Ice!” in a long cry. Other icemen used a bell, but not Mr. Schmitt. I waited for him to come, and we would talk while he stabbed at the great cakes of ice in his hooded wagon, chipping off the pieces we always took — two chunks of fifty pounds each. His skill with the tongs was magnificent, and he would swing a chunk up on his shoulder, over which he wore a sort of rubber chasuble, and move with heavy grace up the walk along the side of our house to the kitchen porch.

“Do you want to ride today?” he would ask, meaning that I was welcome to ride to the end of the block on the high seat above Ted’s rump, where the shiny, rubbed reins lay in a loose knot, because Ted needed no guidance and could be trusted to stop at all the right houses and start up again whenever he felt Mr. Schmitt’s heavy, vaulting rise to the seat. I often rode to the end of the block, and Ted, in the moments when he was still, would look around at me, first from one side, and then the other, and stamp a leg, and shudder his harness against flies, and in general treat me as a member of the ice company, for which I was grateful

What could I buy for Ted? Perhaps in New York they had horse stores. My father would give me what money I would need, when I told him what I wanted to buy. I resolved to ask him, provided I could stay awake until the dinner party was over, and my father, as he always did, would come in to see if all was well. How much love there was all about me, and how greedy I was for even more of it.

The next day we assembled at the station to take the train. It was a heavy, gray, cold day, and everybody wore fur except me and my Great-aunt Barbara Tante Bep. She was going to Germany with my grandfather, her brother.

This was an amazing thing in itself, for, first of all, he usually went everywhere alone, and second, Tante Bep was so different from her magnificent brother that she was generally kept out of sight. She lived across town on the East Side in a convent of German nuns, who received money for her board and room from Grosspa. She resembled an ornamental cork that my grandfather often used to stopper a wine bottle. Carved out of soft wood and painted in bright colors, the cap of the cork represented a Bavarian peasant woman with a blue shawl over painted gray hair. The eyes were tiny dots of bright blue lost in wooden crinkles, and the nose was a long wooden lump hanging over a toothless mouth sunk deep in a poor smile.

Now, wearing her jet-spangled black bonnet with chin ribbons, and her black shawl and heavy skirts that smelled like dog hair, she was returning to Germany with her brother. I did not know why.

But her going was part of the strangeness I felt in all the circumstances of our journey. On the train my grandfather retired at once to a drawing room at the end of our car. My mother went with him. Tante Bep and I sat in swivel chairs in the open part of the parlor car, and my father came and went between us and the private room up ahead.

In the afternoon I fell asleep after the splendors of lunch in the dining car. Grosspa’s lunch went into his room on a tray, and my mother shared it with him. I hardly saw her all day, but when we drew into New York, she came to wake me. “Now, Richard, all the lovely exciting things begin! Tonight the hotel, tomorrow the ship! Come, let me wash your face and comb your hair.”

“And the shopping?” I said.

“Shopping?”

“For my presents.”

“What presents?”

“Mother, Mother, you’ve forgotten.”

“I’m afraid I have, but we’ll speak of it later.”

It was true that people did forget at times, and I knew how they tried then to make unimportant what they should have remembered. Would this happen to me, and my plans for Anna, and Mr. Schmitt, and Ted? My concern was great — but, as my mother had said, there were excitements waiting, and even I forgot, for a while, what it had seemed treachery in her to forget.

We drove from the station in two limousine taxis, like high glass cages on small wheels. My father rode with me and Tante Bep. It was snowing lightly, and the street lamps were rubbed out of shape by the snow, as if I had painted them with water colors. We went to the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Fifth Avenue, and soon after I had been put into the room I was to share with Tante Bep, my father came in to make an announcement. He lifted me up so that my face was level with his. His beautifully brushed hair shone under the chandelier, and his voice sounded the way his smile looked.

“Well,” he said, “we’re going to have a dinner party downstairs in the main dining room.”

I did not know what a main dining room was, but it sounded superb, and I knew enough of dinner parties to know that they always occurred after my nightly banishment to bed.

“It won’t be like at home, will it?” I said. “It will be too far away for me to listen.”

“Listen? You’re coming with us. And do you know why you’re coming with us?”

“Why?”

“Grosspa specially wants you there.”

“Ach Gott,” Tante Bep said in the shadows, and my father gave her a frowning look.

We went downstairs together a few minutes later. I was dazed by the grand rooms of the hotel, the thick textures and velvety lights, the distances of golden air, and most of all by the sound of music coming sweetly and sharply from some hidden place. In a corner of the famous main dining room was a round table sparkling with silver, glass, ice, china and flowers, and in a high-backed armchair sat my grandfather. He leaned forward to greet us, and seated us about him. My mother was at his right, in one of her prettiest gowns. I was on his left.

“Hup-hup!” my grandfather said, clapping his hands to summon waiters. “Tonight nothing but a happy family party, and Richard shall drink wine with us, for I want him to remember that his first glass of wine was handed to him by his alter Miinchner Freund, der Grossvater.”

At this, Tante Bep began to make a wet sound, but a look from my father quelled it, and my mother, blinking both eyes rapidly, put her hand on her father’s and leaned over and kissed his cheek.

“Listen to the music,” Grosspa commanded, “and be quiet, if every word I say is to be a signal for emotion!”

Everybody straightened up and looked consciously pleasant. For me, it was no effort. The music came from within a bower of gold lattice screens and potted palms — two violins, a cello and a harp. I could see the players now, for they were in the corner just across from us. The leading violinist was alive with his music, bending to it, marking the beat with his glossy head, on which his sparse black hair was combed flat. The dining room was full of people, and their talk made a thick hum; to rise over this the orchestra had to work with extra effort.

The rosy lampshades on the tables, the silver vases full of flowers, the slow sparkling movements of the ladies and gentlemen at the tables, and the swallowlike dartings of the waiters transported me. I felt a lump of excitement in my throat. My eyes kept returning to the orchestra leader, who conducted with jerks of his nearly bald head, for what he played and what he did seemed to emphasize the astonishing fact that I was at a dinner party in public.

“What are they playing?” I asked. “What is that music?”

“It is called II Bacio,” Grosspa said.

“What does that mean?”

“It means ‘The Kiss.”‘

What an odd name for a piece of music, I thought. All through dinner — which did not last as long as it might have — I inquired about pieces played by the orchestra, and in addition to the Arditi waltz, I remember one called Simple Aveu, and the Boccherini Minuet. The violins had a sweetish, mosquitolike sound, and the harp was breathless, and the cello mooed like a distant cow, and it was all entrancing. Watching the orchestra, I ate absently, chewing hardly at all, until my father, time and again, turned me back to my plate. And then a waiter came with a silver tub on legs, which he put at my grandfather’s left, and took the wine bottle from its nest of sparkling ice and showed it to him. The label was approved, and a sip was poured for my grandfather to taste. He held it to the light and twirled his glass slowly; he sniffed it, and then he tasted it.

“Yes,” he declared, “it will do.”

My mother watched this ritual, and over her lovely heart-shaped face, with its rolled crown of silky hair, I saw memories pass like shadows, as if she were thinking of all the times she had watched this business of ordering and serving wine. She blinked her eyes again and, opening a little jeweled lorgnon she wore on a fine chain, bent forward to read the menu that stood in a little silver frame beside her plate. But I could see that she was not reading, and I wondered what was the matter with everybody.

“For my grandson,” Grosspa said, taking a wineglass and filling it half with water, and then to the top with wine. The yellow wine turned even paler in my glass, but there was too much ceremony for me not to be impressed. When he raised his glass, I raised mine, and while the others watched, we drank together. And then he recited a proverb in German which meant something like:

When comrades drink red wine or white,

They stand as one for what is right,

and a flourish of intimate applause went around the table in acknowledgment of this stage of my growing up.

I was suddenly embarrassed, for the music had stopped, and I thought all the other diners were looking at me; many were, in fact, smiling at a boy of 10, ruddy with excitement and confusion, drinking a solemn pledge of some sort with an old gentleman with a pink face and very white hair and whiskers.

Mercifully, the music began again, and we were released from our pose. My grandfather drew his great gold watch from his vest pocket and unhooked from a vest button the fob that held the heavy gold chain in place. Repeating an old game we had played when I was a baby, he held the watch toward my lips, and I knew what was expected of me. I blew upon it, and — though long ago I had penetrated the secret of the magic — the gold lid of the watch flew open. My grandfather laughed softly in a deep, wheezing breath, and then shut the watch.

“Do children ever know that what we do to please them pleases us more than it does them?” he said.

“Ach Gott,” whispered Tante Bep, but nobody reproved her.

“Richard, I give you this watch and chain to keep all your life, and by it you will remember me,” my grandfather said.

“Oh, no!” exclaimed my mother.

He looked gravely at her and said, “Yes. Now, rather than later,” and put the heavy, wonderful golden objects in my hand. I regarded them in stunned silence. Mine! I could hear the wiry ticking of the watch, and I knew that now and forever I myself could make the gold lid fly open.

“Well, Richard, what do you say?” my father urged gently.

“Yes, thank you, Grosspa, thank you.”

I half rose from my chair and put my arm around his great head and kissed his cheek. Up close, I could see tiny blue and scarlet veins under his skin.

“That will do, my boy,” he said. Then he took the watch from me and handed it to my father. “I hand it to your father to keep for you until you are 21. But remember that it is yours and you must ask to see it anytime you wish.”

My disappointment was huge, but even I knew how sensible it was for the treasure to be held for me instead of given into my care.

“Any time you wish. You wish. Any time,” repeated my grandfather, but in a changed voice, a hollow, windy sound that was terrible to hear. He was gripping the arms of his chair and now he shut his eyes behind his gold-framed lenses, and sweat broke out on his forehead. “Any time,” he tried to say through his suffering, to preserve a social air. But, seized by pain too merciless to hide, he lost his pretenses and staggered to his feet. Quickly my mother and father helped him from the table, while other diners stared with neither curiosity nor pity. I thought the musicians played harder all of a sudden to distract people from the sight of an old man in trouble being led out of the main dining room of the Waldorf-Astoria.

“What is the matter?” I asked Tante Bep, who had been ordered, with a glance, to remain behind with me.

“Grosspa is not feeling well.”

“Should we go with him?”

“But your ice cream.”

“Yes, the ice cream.”

So we waited for the ice cream, and in a moment or two the flow and rustle of rosy-shaded life was once again in the room.

My parents did not return from upstairs, though we waited. Finally, hot with wine and excitement, I was led by Tante Bep to the elevator and to my room and put to bed. Nobody came to see me, or if anyone did, I did not know it.

More snow fell during the night. When I woke up and ran to my window, the world was covered and the air was thick with snow still falling. Word came to dress quickly, for we were going to the ship. Suddenly I was consumed with eagerness to see the great ship that would cross the ocean.

Again we went in two taxicabs, I with my father. The others had gone ahead of us. My father pulled me near him to look out the window of the cab at the falling snow. We went through narrow, dark streets to the piers on the west side of Manhattan, where we boarded the ferryboat that would take us to Hoboken.

“We are going to the docks of the North German Lloyd,” my father said.

“What is that?”

“The steamship company where Grosspa’s ship is docked. The Kronprinzessin Cecilie.”

“Can I go inside her?”

“Certainly. Grosspa wants to see you in his cabin.”

“Is he there now?”

“Probably. The doctor wanted him to go right to bed.”

“Is he sick?”

“Yes.”

“Did he eat something — ” (It was a family explanation often used to account for my various illnesses at their onset.)

“Not exactly. It is something else.”

“Will he get well soon?”

“We hope so.”

He looked out the window as he said this, instead of at me, and I thought, He does not sound like my father. But we had reached the New Jersey side now, and the cab was moving past the docks. Above the gray, snowy sheds I saw the funnels and masts of ocean liners. The streets were furious with noise, horses, cars, porters running, and suddenly a white tower of steam rose from the front of one of the funnels, to be followed in a second by a deep, roaring hoot.

“There she is,” my father said. “That’s her first signal for departure.”

It was our ship. I could see her masts with their pennons being pulled about by the blowing snow, and her four tall ocher funnels.

We went from the taxi into the freezing air of the long pier. All I could see of the Kronprinzessin Cecilie were glimpses, through the pier shed, of white cabins, rows of portholes, and an occasional door of polished mahogany. A confused, hollow roar filled the long shed. We went up a canvas-covered gangway and then we were on board. There was an elegant creaking from the shining woodwork. I felt that ships must be built for boys, because the ceilings were so low and made me feel so tall.

My father held my hand to keep me by him on the thronged decks, and then we entered a narrow corridor that seemed to have no end. The walls were of dark, shining wood, and there were weak yellow lights overhead. The floor sloped down and then up again, telling of the ship’s construction. Cabin doors were open on either side. There was a curious odor in the air, something like the smell of soda crackers dipped in milk, and faraway — or was it right here, all about us in the ship — there was a soft throbbing sound. It seemed impossible that anything so immense as this ship would presently detach itself from the land.

“Here we are,” my father said, at a half-open cabin door.

We entered my grandfather’s room, which was not like a room in a house, for none of its lines squared with the others but met only to reflect the curvature of the ship. Across the room, under two portholes whose silk curtains were drawn, my grandfather lay in a narrow brass bed. He lay at a slight slope, with his arms outside the covers, and he wore a white nightgown. I had never before seen him in anything but his formal day and evening clothes. He looked white — there was hardly a difference of color between his beard and his cheeks and his brow. He did not turn his head, only his eyes. He seemed suddenly dreadfully small, and fearfully cautious, where be- fore he had gone his way magnificently, ignoring whatever threatened him with inconvenience, rudeness or disadvantage. My mother stood by his side, and Tante Bep was at the foot of the bed, wearing her black shawl and peasant skirts.

“Yes, come, Richard,” Grosspa said in a faint, wheezy voice, looking for me without turning his head.

I went to his side, and he moved his hand an inch or two toward me — not enough to risk such a pain as had thrown him down the night before, but enough to call for a response. I gave him my hand and he tightened his fingers over mine.

“Will you come to see me?” he said.

“Where?” I asked in a loud, clear voice. My parents looked at each other, as if to inquire how in the world the chasms which divide age from youth, and pain from health, and sorrow from innocence could ever be bridged.

“In Germany,” he whispered. He shut his eyes and held my hand, and I had a vision of Germany which may have been sweetly near his own; for what I saw were the pieces of brilliantly colored cardboard scenery that belonged to the toy theater he had once brought me from Germany.

“Yes, Grosspa,” I replied, “in Germany.”

“Yes,” he whispered, opening his eyes and making the sign of the Cross on my hand with his thumb. Then he looked at my mother, who understood at once.

“You go now with Daddy,” she said, “and wait for me on deck. We must leave the ship soon. Schnell, now, skip!”

My father took me along the corridor and down the grand stairway. The ship’s orchestra was playing somewhere — it sounded like the Waldorf. We went out to the deck just as the ship’s whistle let go again, and now it shook me gloriously and terribly. I covered my ears, but still I was held by that immense, deep voice. For a moment, when it stopped, the ordinary sounds around us did not come close. It was still snowing — heavy, slow, thick flakes, each like several flakes stuck together.

A cabin boy came along beating a brass cymbal, calling out for all visitors to leave the ship.

I began to fear that my mother might be taken away to sea after my father and I were forced ashore. I saw her at last. She came toward us with a rapid, light step and, saying nothing, turned us to the gangway, and we went down. She was wearing a little spotted veil, and with one hand she lifted it and put her handkerchief to her mouth. She was weeping and I was abashed by her grief.

We hurried to the dock street, and there we lingered to watch the Kronprinzessin Cecilie sail.

We did not talk. It was bitter cold. Wind came strongly from the West, and then, after a third great whistle-blast the ship slowly began to change — she moved like water itself as she left the dock, guided by three tugboats that made heavy black smoke in the thick air. At last I could see all of the ship at one time.

I was amazed how tall and narrow she was. Her four funnels rose like a city’s chimneys against the blowy sky. Stern first, she moved out into the river. I squinted at her with my head on one side and knew exactly how I would make a small model of her when I got home. In midstream she turned slowly to head toward the Lower Bay. She looked gaunt and proud and top-heavy as she ceased backing and turning and began to steam down the river and away.

“Oh, Dan!” my mother cried in a broken sob, and put her face against my father’s shoulder. He folded his arm around her. Their faces were white. Just then a break in the sky across the river lightened the snowy day, and I stared in wonder at the change. My father, watching after the liner, said to my mother: “Like some wounded old lion crawling home to die.”

“Oh, Dan,” she sobbed, “don’t, don’t!” I could not imagine what they were talking about. I tugged at my mother’s arm and said with excitement, pointing to the thick flakes everywhere about us, and against the light beyond, “Look, look, the snowflakes are all black!”

My mother suddenly could bear no more. She leaned down and shook me, and her voice was strong with anger: “Richard, why do you say black! What nonsense. Stop it. Snowflakes are white, Richard. White! White! When will you ever see things as they are! Oh!”

“Come, everybody,” my father said. “I have the taxi waiting.”

“But they are black!” I cried.

“Quiet!” my father commanded.

We were to return to Dorchester on the night train. All day I was too proud to mention what I alone seemed to remember, but after my nap, during which I refused to sleep, my mother came to me.

“You think I have forgotten,” she said. “Well, I remember. We will go and arrange for your presents.”

My world was full of joy again. The first two presents were easy to find — there was a little shop full of novelties a block from the hotel, and there I bought for Anna a folding package of views of New York and for Mr. Schmitt a cast-iron savings bank, made in the shape of the Statue of Liberty, to receive dimes. It was harder to think of something Ted would like. My mother let me consider many possibilities among the variety available in the novelty shop, but the one thing I wanted for Ted I did not see. Finally I asked the shopkeeper: “Do you have any straw hats for horses?”

“What?”

“Straw hats for horses, with holes for their ears to come through. They wear them in summer.”

“Oh. I know what you mean. No, we don’t.”

My mother took charge. “Then, Richard, I don’t think this gentleman has what we need for Ted. Let’s go back to the hotel. I think we will find it there.”

“What will it be?”

“You’ll see.”

When tea had been served in her room, she asked, “What do horses love?”

“Hay. Oats.”

“Yes. What else?”

Her eyes sparkled playfully. I followed her glance, and knew the answer.

“I know! Sugar!”

“Exactly” — and she made a little packet of sugar cubes in a Waldorf envelope from the desk in the corner, and my main concern about the trip to New York was satisfied.

At home I could not wait to present my gifts. Would they like them? Whether Anna and Mr. Schmitt did or not, I never really knew. Anna accepted her folder of views and opened it up to let the pleated pages fall in one sweep, and said, “When we came to New York from the old country I was a baby and I do not remember one thing about it.” Mr. Schmitt took his Statue of Liberty savings bank, turned it over carefully, and said, “Well. . . ”

But Ted — Ted very clearly loved my gift, for he nibbled the sugar cubes off my outstretched palm until there were none left, and then he bumped at me with his hard, itchy head, making me laugh and hurt at the same time.

“He likes sugar,” I said to Mr. Schmitt.

“Ja. Do you want to ride?”

Life, then, was much as before until the day, a few weeks later, that we received a cablegram telling us that my grandfather had died in Munich. My father came home from the office to comfort my mother. They told me the news in our long living room, with the curtains drawn. I listened, a lump of pity came into my throat for the look on my mother’s face, but I did not feel anything else.

“He dearly loved you,” they said.

“May I go now?” I asked.

They were shocked. What an unfeeling child. Did he have no heart? How could the loss of so great and dear a figure in the family not move him?

But I had never seen anything dead; I had no idea of what death was like; Grosspa had gone away before and I had soon ceased to miss him. What if they did say now that I would never see him again? They shook their heads and sent me off.

Anna was more offhand than my parents. “You know,” she said, letting me watch her work at the deep zinc laundry tubs in the dark, steamy basement, “that your Grosspa went home to Germany to die, don’t you?”

“Is that the reason he went?” I asked.

“That’s the reason.”

“Did he know it?”

“Oh, yes, sure he knew it.”

“Why couldn’t he die right here?”

“Well, when our time comes, maybe we all want to go back where we came from.”

Her voice contained a doleful pleasure, but the greatest mystery in the world was still closed to me. When I left her, she raised her old tune under the furnace pipes, and I wished I was as happy and full of knowledge as she was.

My time soon came.

On the following Saturday, I was watching for Mr. Schmitt and Ted when I heard heavy footsteps running up the front porch and someone shaking the door knob, as if he had forgotten there was a bell. I went to see. It was Mr. Schmitt. He was panting and he looked wild. When I opened the door, he ran past me, calling out, “Telephone! Let me have the telephone!”

I pointed to it in the front hall, where it stood on a gilded wicker taboret. He began frantically to click the receiver hook. I was amazed to see tears roll down his cheeks.

“What’s the matter, Mr. Schmitt?”

I heard my mother coming along the upstairs hallway from her sitting room.

Mr. Schmitt put the phone down suddenly and pulled off his hat, and shook his head. “What’s the use?” he said. “I know it is too late. I was calling the ice plant to send someone.”

“Good morning, Mr. Schmitt,” my mother said, coming downstairs. “What on earth is the matter?”

“My poor old Ted,” he said, waving his hat toward the street. “He just fell down and died up the street in front of the Weiners’ house.”

I ran out of the house and up the sidewalk to the Weiners’ house, and sure enough, there was the ice wagon, and still in the shafts, lying heavy and gone on his side, was Ted.

There lay death on the asphalt pavement. I confronted the mystery at last. The one eye that I could see was open. Ted’s teeth gaped apart, and his long tongue touched the street. His body seemed twice as big and heavy as before. His front legs were crossed, and the great horn cup of the upper hoof was slightly tipped, the way he used to rest it in ease. In his fall he had twisted the shafts that he had pulled for so many years. His harness was awry. Water dripped from the back of the hooded wagon. Its wheels looked as if they had never turned. What would ever turn them?

“Never,” I said, half aloud. I knew the meaning of this word now.

In another moment my mother came and took me back to our house, and Mr. Schmitt settled down on the curbstone to wait for people to arrive and take away the leavings of his changed world.

“Richard,” my mother said, “don’t go out again until I tell you.”

I went and told Anna what I knew. She listened with her head to one side, her eyes half closed, and she nodded at my news and sighed.

“Poor old Ted,” she said, “he couldn’t even crawl home to die.”

This made my mouth fall open, for it reminded me of something I had heard before, and all day I was subdued and private. Late that night I woke in a storm of grief so noisy that my parents heard the wild gusts of weeping and came to ask what the trouble was.

I could not speak at first, for their tender, warm, bed-sweet presences doubled my emotion, and I sobbed against them as they held me. But at last, when they said again, “What’s this all about, Richard? Richard?” I was able to say brokenly, “It’s all about Ted.”

It was true, if not all the truth, for I was thinking also of Grosspa crawling home to die, and I knew what that meant now, and what death was like. I imagined Grosspa’s heavy death, with one eye open, and his sameness and his difference all mingled, and I wept for him at last, and for myself if I should die, and for my ardent mother and my sovereign father, and for the iceman’s old horse, and for everyone.

“Hush, dear, hush, Richard,” they said.

A pain in my head began to throb remotely as my outburst diminished, and another thought entered. I said bitterly: “But they were black! Really they were!”

They looked at each other and then at me, but I was too spent to continue, and I fell back on my pillow. Even if they insisted that snowflakes were white, I knew that when seen against the light, falling out of the sky into the dark water all about the Kronprinzessin Cecilie, they were black. Black snowflakes against the sky. Black.

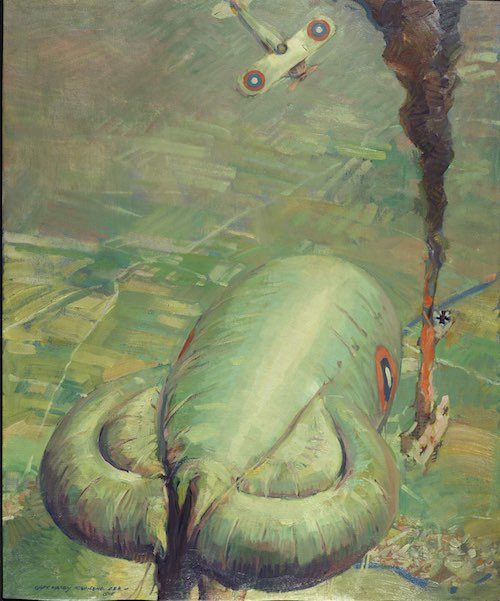

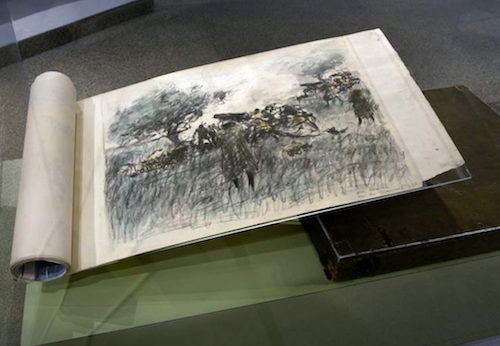

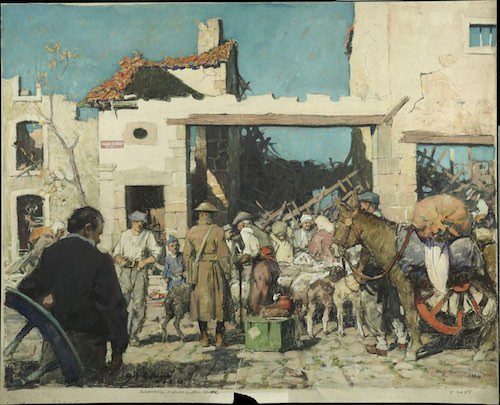

The Art of the Post: Forgotten Art Treasures from World War I

A hundred years ago, a select group of talented artists worked on the front lines of World War I, drawing and painting the human drama of The Great War. They captured the bravery and fear along with the boredom and exhaustion. But after the war ended, their eyewitness art was exhibited just once and then placed in storage at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Pictures of the human cost of the war — of flaming aerial combat around observation blimps, of poison gas attacks, of sacrifice and dedication — were quietly filed away in dark drawers where they’ve remained ever since, for the most part unseen and unappreciated by the public.

Now with the hundredth anniversary of America’s entry into World War I, these artworks have been rediscovered and placed on display in a wonderful and fitting exhibition by the Smithsonian, a joint project of the National Air and Space Museum and the National Museum of American History.

Our story begins in 1917, when some of America’s finest illustrators left their comfortable homes and families to work on the front lines of the “war to end all wars.” One of the artists, Harry Townsend, later wrote in his war diary, “I had gotten drunk, as it were, with the future pictorial possibilities in what I saw, and what my imagination saw, in the warfare that was so soon to come.”