Well, and how do you like Spain?” the driver said, turning round to him at the stoplight, presenting his gray face with its wrinkles and scaly skin. Generations of hungry ancestors were involved in the production of that face; it had taken centuries to form.

“Spain? I like it very much,” Simmons replied.

“And so you should,” the driver said, “for after all, it is of your making.”

Simmons made no attempt to understand this. He merely said, “It is true,” one of many Spanish phrases he had learned from a book for tourists, part of his quick refresher course.

Simmons relaxed. Trying to understand a foreign language was such a strain; after a week in Madrid, even his muscles felt sore. The taxi, he thought, rode with remarkable smoothness. Like most Spanish taxis, it seemed to have been constructed out of several other cars, and bore not the mark of any known maker but only of some welder’s craft. They’re really very good at this sort of thing, Simmons thought. He didn’t know why, but he found something sordid in this kind of construction. There was a cunning in it.

Inwardly, Simmons practiced a tolerant laugh. He wanted very much not to be the kind of American tourist all his friends had returned to tell him about. At the same time, he did not consider himself an American ambassador abroad, but simply a civilized man.

Besides, he had worked too long and too hard, for more than 15 years — for 15 solid years, as he put it — to play any role other than that of a man out to enjoy and indulge himself. God knows I’ve earned it, he said, looking out of the taxi window at the shops and cafés, and, disapprovingly, at the rather too large sky which was like a silver dome specially designed and constructed for Madrid. He did not think this provincial capital deserved such a sky; it was too grand for such a poor, depleted place.

This thought was one which Simmons, in any case, would not have lingered on, but it was almost immediately driven from his mind by the sight of a group of young women. The girls of Madrid had surprised him; so many were blonde and wore copies of Chanel suits. Even now after a week, it still came as a surprise to him. He had imagined that all Spanish women looked like those he had seen as a boy on the insides of cigar-box lids: dark, voluptuous, somnolent. Well, well, he said to himself, tolerant of his own mistakes.

He was on his way now to the tailor, for the final fitting of his suit. This was to be his first tailor-made suit, and he found that it was, in its own way, quite thrilling: the fact that this suit was made for him, was his alone, and could never, not possibly, fit anyone else the way it fit him.

He had already rehearsed several stories which began, magically, with the words: “My tailor.” Or better still: “My tailor in Madrid.” He took this suit as a sign of his having arrived, of having made it in the world. He saw it as the guarantee of final success; and he thought it interesting that, after his first visit to the tailor, the whole trip had taken on a new aspect: It had come to give him a foretaste of retirement, of those years when he’d have all the insurance paid up, money in the bank, dividends rolling in, and not a worry in the world.

Simmons was happy with his wife, and their marriage, though childless, had been a satisfactory one; he had no doubt it would continue so. He was forty-five and in good health, but he found that he was looking forward to old age, to retirement, to being, as he put it, on the beach.

This trip had given him the time to think in a much more composed way about the prospect of retirement. Simmons liked to plan ahead. Now he saw them — the years ahead — no longer as a completely vacant expanse. The notion came to him with startling clarity and suddenness: He would spend his retirement visiting the tailor, having suits made.

The vision was repugnant. Where do these thoughts come from?, he asked himself, appalled; and he applied himself once again to the seeing of sights from the taxi window. Well, well, he said. He thought it must have something to do with the change of water.

It was the water, yes; and the change of air; and the general shock of foreignness. It had begun, he remembered, the very night of the day that he and his wife, Roberta, had arrived in Spain. He had spent the afternoon in the hotel room, resting from the flight, writing letters and cards to friends back home. When he and Roberta went out for dinner that night — all the guidebooks had warned about the late dinner hour in Spain, and so they did not leave the hotel until after nine — he took the letters to the desk clerk and bought airmail stamps. There were three stamps for each letter and two for the cards, and while he was paying for them the clerk hit the bell and cried, “Botones!”

The bellboy appeared at Simmons’s side; he wore a pale blue uniform with two rows of buttons on his short jacket. Simmons thought at first that he was a midget, but after a moment saw he was indeed a boy, perhaps 12 years old. Simmons was outraged that a child so young should be working, and worse, that he should be kept up so late.

When Simmons picked up the first stamp and was about to begin stamping his letters, the clerk said, “That’s all right, sir. Buttons will lick them for you.” Simmons was shocked, but it suddenly occurred to him that if he stamped the letters himself, the boy would get no tip.

“Yes, of course,” he said, without looking at the clerk or the boy. He gave the child 10 pesetas and walked away, warmed for a moment by the sense of his own generosity. Ten pesetas was 17 cents. Seventeen cents must seem an enormous sum to that boy. When he got outside, he remembered that he had figured this out according to the official rate of exchange, but he had not bought his pesetas at the official rate, and he realized that after all he had given the boy only a dime. Still, he thought, even a dime to that child is quite a nice sum; and it was at that moment he had his first ugly vision.

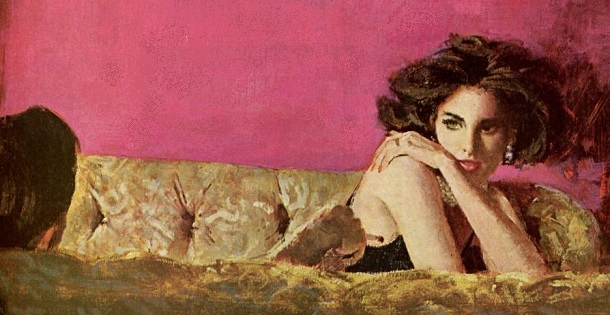

He saw himself filling a bowl, a rather good-sized bowl, with mucilage, and presenting it to the boy to eat. He poured the mucilage out of a bottle he had not seen since childhood. It was LePage’s mucilage, and he saw, with absolute clarity, the bright red and black and yellow of the label, the florid lettering. It was a disgusting vision, and he got rid of it as quickly as he could, and fortunately was able to do so by the time they got to a well-recommended restaurant. Late as it was, they were still the first to have appeared, but Roberta said, “Never mind, dear,” and the headwaiter seemed genuinely pleased to see them. The food was excellent, and Roberta, he noticed after a while, looked exceptionally pretty. He had forgotten what nice shoulders she had. The low-cut dress she wore was really quite revealing, and he caught himself staring at her breasts. When he looked up, Roberta had on her face that expression he had come to know so well. She seemed always to be waiting for something.

When they returned to the hotel at midnight — they were tired from the flight, and the food and wine had made them very sleepy — the bellboy was still on duty. He smiled, and it seemed to Simmons, lightheaded as he was, that the boy was saying, “I shall never forget you, sir.” Simmons nodded, very pleased, and returned the smile.

The night manager, who spoke English very well, came out of his office and, on behalf of the entire night staff, welcomed Simmons and his wife to the hotel, and put himself, personally, at their disposal. Simmons said, “Actually, you probably could be of help to me. I want to have a suit made. I’ve been given the name of a tailor, Santander Brothers, and I wonder if you could — ”

“Of course,” the night manager said. “Yes, they have an excellent reputation and are well-esteemed; but here in Madrid we are famous for our tailors. There are many good ones, and many who are, though less well-known, as good as the Brothers Santander and not so expensive.”

“Is that so?” Simmons said.

The night manager, with fantastic dexterity, produced a card from his vest pocket, and with the desk clerk’s pen wrote down the name and address of a highly esteemed tailor for Simmons. “I could even make the appointment for you, sir,” the manager said.

In this way it had all been arranged; and it pleased Simmons very much, because now he had a tailor of his own, one he had himself discovered and who was not even mentioned in the guidebooks.

“Well, here we are,” the driver said, offering Simmons another view of his relic of a face, “and it has really been a pleasure to carry you.”

Simmons leaned forward to read the meter, reached into his pocket, and calculated the tip. He got out of the cab, looking up at the now familiar building where his tailor was, perhaps even at this moment, sewing the last stitch on his first handmade suit. Simmons thought, How odd; I have advanced to what my grandfather took for granted. And he suddenly saw history, the march of generations, as a crazy geometry, an elliptic and eccentric spiral, impossible to read, without sense. It left him with a feeling of vertigo.

The cold handle of the bronze-and-glass door restored him; the marble floor and walls of the lobby reassured him. Near the ceiling there were carved borders of roses and angels. He stopped to marvel at the profligacy of it, not of materials only but of time itself. How had they found so much of it? How had they managed? He thought that time was a product peculiar to the nineteenth century, a natural resource which had begun to run thin and never survived into his century.

There was an elevator, but his tailor was on the second floor and Simmons took the stairs; he had read that such exercise, in moderation, was good for the heart. Having a President who had suffered a heart attack had made Simmons and his friends very sensitive to such things. Heart specialists on television and in newspapers made them aware they all had that tough and fragile thing inside them; sometimes Simmons thought he was merely a protective shell designed, and assigned, to protect this tricky mechanism. Occasionally he even put his hand to his chest, to assure himself that it was still running.

He took deep breaths as he climbed the stairs, consciously giving exercise and oxygen to the masterful thing whose captive he was.

At the top of the stairs, on the second floor, Simmons paused and allowed his breathing to regulate itself. Here the walls were of ordinary plaster and the floor of wood. Time, apparently, ran out when the builders got up here. But the corridor was twice as wide as those in modern buildings, which showed how hard it was to break the habit: They still thought they had a little time left over and had converted it into space. No more carved roses, true, but expansiveness was itself a decoration.

His tailor, Mr. Nuñez, was a young man, perhaps thirty, with a seamed face and a small moustache. This moustache lived a life of its own: Even when Nuñez’s face was in complete control of itself, the moustache twitched and fluttered, as if eager to be off or itching to grow larger. Nuñez’s eyes indicated that he was not unaware of this phenomenon, and he often looked at Simmons apologetically, as if to say, “I would let it grow bigger, believe me I would, but I can’t afford to.”

The shop was small, and only a little light, cloudy and uncertain, leaked through the window; in amount it was equal to that given off by the bare bulb which hung dead center from the ceiling, trembling with each footfall, depending from a desiccated electric cord which had begun to curl up, as if from shame. There was more light produced by the reflecting surfaces of mirror and pressing iron, and the glass covering the large photograph of Nuñez’s father. Along one wall were metal shelves which provided more than enough space for the few bolts of cloth which represented Nuñez’s meager stock. Among this very limited selection Simmons had found exactly what he was looking for: a very English Glen plaid which was, nevertheless, a product of a textile mill north of Barcelona.

As soon as Nuñez closed the door behind his American client, he leaped onto his worktable, crossed his rickety legs, and, in the same movement snatched up the jacket of Simmons’ suit and took it to his mouth, as if he were going to eat it. Simmons almost cried out in alarm, but Nuñez merely bit the thread, said, “Finished!” and with a magician’s flourish, held up the coat, slid down from the table, an approached the suit’s new owner.

He helped Simmons out of his old suit and into the new one. When the moment came, when finally Simmons slipped his arms into the sleeves of the new coat, it was not a fitting but an investiture. He smiled at his image in the mirror, at his marvelous newness, at the sensation of fulfillment which this suit gave him. It was a construction; it was armor; it was his alone. The lapels were wider than those he was accustomed to, and the shoulders were rather heavily padded in the Latin way. He moved his torso within the shell of the jacket, and his smile widened. He liked, really liked, the way this suit proclaimed its foreignness. There’d be no need to tell anyone anything. This suit was a fact. Even strangers would know him for what he was: a man who had arrived.

“You like it, sir?”

“Very good,” Simmons answered, “very, very good.” He put his hand into the trouser pocket and was momentarily alarmed to find no money there. He picked up his old suit and transferred the contents of the pockets.

Nuñez was delighted that his craft had produced such results. He clapped his hands and said, “All is precisely as I had wished it to be.”

With a few words and gestures Simmons conveyed to his tailor that he would like the old suit wrapped. He counted out pesetas to the value of 45 dollars, and his tailor wrote out the receipt. Copperplate, Simmons thought, watching it roll off the point with magical fluency and exactitude, as if the writing had been contained in the barrel of the pen and was now not so much written on the paper as released onto it. Nuñez took three tax stamps from a box and affixed them to the receipt. Everything but sealing wax, Simmons thought.

He turned away and looked at himself once again in the mirror. He saw a cardboard box materialize on the table behind him, and then the tailor carefully folded and packed the old suit. Simmons prepared a sentence in Spanish; his few hours of brushing up in this language had suddenly begun to pay off; phrases long ago forgotten now amazingly returned, and the sentence formed itself with fantastic ease.

“The women of Madrid astonish me,” he said. “So beautiful and well dressed.”

“Well dressed, yes.” Nuñez said. “But their stomachs . . .” And here he made with the four fingers and thumb of his right hand a beak, the fingers stiff and hard, and he rapidly opened and closed the beak of this bird which had suddenly grown from his wrist.

“Surely not.” Simmons said. “But there is such an air of prosperity.” Once again, and this time without preparation, the words rolled from his tongue, as they had come from the barrel of Nuñez’s pen.

The tailor said nothing. He tied the last knot on the box.

Simmons rolled his shoulders, trying to accustom himself to the padding of the jacket. I feel like an all-American halfback, he said to himself, lightly. Nuñez now had lighted a candle and was heating the end of a brown stick of t wax which had appeared in his hand. He dripped wax onto the knot; it puddled and formed itself into a ragged circle. Nuñez touched the end of the stick of wax, testing it for coolness; and then with a stubby metal bit he pressed the wax four times, leaving the die’s mark on the seal.

Too perfect, Simmons thought; no one will believe it. He put the receipt in his wallet and picked up the box, careful to keep his sleeve clear of the wax. He shook hands with Nuñez and said, “Thank you very much. It has been a great pleasure, and I hope to return, and I will certainly send my friends.”

Nuñez smiled and held the door open for him. Simmons took the elevator down. In the taxi he studied the wax seal, trying to read the tailor’s mark, but it was very small. He was not sure, but he thought it must be a bird of some sort; something winged, surely, perhaps a swan.

When he got back to the hotel, he saw Roberta in the lobby, having tea. Only when he stood by her table did she recognize him. “Good heavens,” she said. “I thought you were a Spanish gentleman on the make.”

He laughed, delighted. “Do you like it?”

“Marvelous,” she said. “But it may take me a little while to get used to those shoulders. You taper like a lifeguard.”

He laughed, sat down beside her on a velvet love seat, and turned sideways to the table; he crossed his legs carefully and sat forward so the jacket would hang right. Whenever anyone entered the lobby he looked up to see if he had been noticed. He was very pleased. Later, when he and Roberta returned to the hotel from dinner, the night manager spread his arms as if about to embrace Simmons and said, “Ahhhh, perfect!”

Simmons and his wife left next day for Paris, and a week later were in London. His delight in the new suit did not diminish; he found that whether he wore it on the plane or packed it in a suitcase it remained unwrinkled; it maintained itself in armorial perfection. Simmons noticed, or believed he noticed, that on the days he wore his old American suits, waiters and doormen did not move for him with the same respectful haste as they did when he wore his Spanish suit. The suit gave him something, he had no doubt; it marked him, he was certain, as someone out of the ordinary, someone very special.

It had been a quite perfect trip; even before it was over Simmons was seeing it in retrospect, had begun to reminisce several days before they boarded the boat at Southampton. In Paris, he had bought Roberta a long string of pearls, and in London he bought her antique silver objects. She wore the pearls wrapped around her neck so that they formed a high collar, a nacreous shell around the tower of her throat. It was obvious she liked them very much, and the silver too; but it was just as obvious to Simmons that he had not yet found that one thing which she wanted above all, because she still greeted him every morning with the same expression on her face, what Simmons had long ago begun to call her “waiting look.” Sometimes he thought her sadness was the result of childlessness. Years back, when it was still a problem to be talked about, the doctor had advised her to face reality. Simmons had no trouble at all in doing so; and he had thought Roberta had none either, but he could be wrong about that, he told himself.

Still, even so, he had to say that the trip had been an unqualified success; when he got back home he would have nothing but good to report. It is true that in Paris several packs of cigarettes had been stolen from his hotel room, but this was a small matter. It bothered him a little because they were not American cigarettes; he knew how Europeans were about American cigarettes, and he could well understand some chambermaid or porter taking a pack or two of Luckies. But Simmons smoked the cigarettes of the country he was in; it was always possible to find a filter tip with blond tobacco. Even in Spain he had no trouble about this and smoked a brand called Bisonte. It had been, in fact, two leftover packs of these cigarettes which were stolen.

Small matter. He did not bother mentioning it to the management.

Also, he had been told that in the great hotels of Europe one could still find the kind of service a Victorian traveler would have taken for granted, the kind of service men of Simmons’s generation had really never known. He had had visions of men in little aprons polishing door handles and brass plates, chambermaids in starched uniforms with armfuls of linen, a housekeeper with a large ring of keys on her belt. And it is true that in his hotels in Paris and London he did see these things, occasionally; but it was perfectly clear that the standards had gone down. They almost never bothered to empty his ashtrays; and oddly enough, in both hotels he had noticed orange peels under his bed.

But such things were merely cause for raised eyebrows, and he would surely have forgotten all about them by the time he got home if the same thing had not happened on the boat. They returned on one of the great English liners, and, on coming back to his cabin one night, he discovered that his last pack of cigarettes had been stolen. He rang for the steward. No, he said to Roberta, no, it wasn’t the lousy 20 cents or whatever, he just damn well wanted a smoke and there wasn’t any.

“But this just doesn’t happen in first class, sir,” the steward said, genuinely shocked.

“It has happened now,” Simmons said.

The steward held a small silver tray against his leg; the vibration of the ship’s engines was reflected there, a subtle agitation. “I shall have to inform the purser, sir,” the steward said, but obviously he was reluctant to do so.

“Never mind,” Simmons said, reminding himself that he was after all a civilized man. “Just see if you can get me a pack of cigarettes, won’t you?” He was sorry he wasn’t wearing his Spanish suit; he was certain his words would have carried more weight.

The steward smiled gratefully. “Have mine, sir, if you don’t mind English cigarettes.”

He handed Simmons a rumpled pack of Ovals. Simmons thanked him and said he would take only two, one for now and one for the morning.

“No trouble at all, sir. Keep the pack. I can always get another from one of my mates.”

“Thank you very much then, steward.”

He closed the door and began to undress; he lit a cigarette and noticed the ashtray was full of butts again. He shook his head.

“I think you handled the whole thing very well, dear,” Roberta said.

Later he was glad he had taken the whole pack, for he woke in the middle of the night and could not fall back to sleep. A noise had wakened him, he supposed; through the porthole he watched the moonlight tilt and shift. When the ship lunged to starboard, the closet door swung open and struck the bulkhead, making a soft, hollow sound. He could see his Spanish suit twisting on its hanger, as if it were anguished by captivity and longing to be free. Now, rocked by the ship, touched by moonlight, he permitted entry to unfamiliar notions and wondered what he was taking back with him, what presence hid in his new suit and waited to be smuggled through customs to the promised land, a furtive stowaway leaving a trail of orange peels and stolen cigarette ends.

Except for the orange peels and the ashtrays, it was a pleasant and uneventful crossing. On the last day he woke early and came out on deck in time to see Coney Island slide smoothly by, mysterious and faintly sinister in the mist of morning. Surreptitiously, although he was alone on deck, he slipped his hand under the slightly too wide lapel of his new suit, and let it rest for a moment on his heart. It seemed fine, in good order. He would walk around the deck once before breakfast, for exercise, and to stimulate his appetite.

Four hours later they were in their apartment. Simmons was on the telephone to his office, and Roberta was removing dust sheets from the furniture; they were speckled with the city’s dirt, the greasy soot that seemed to penetrate the glass of the windows; no way to keep it out. By early afternoon the refrigerator was producing ice cubes again and was full of fruit and meat delivered by the Puerto Rican grocery boy; the suitcases were unpacked; and Simmons decided he would, after all, go down to his office and just have a look-see at his mail. It was too hot in New York for the new suit, but he was determined to wear it on his first day back. Then he would have it cleaned and put away until fall, he told himself.

His secretary greeted him with nervous joy; her white teeth flashed messages of welcome. She always made him feel like a hero just returned from a dangerous mission, even though most of the time he was only coming back from lunch. “Love your suit,” she said.

He told her all about the tailor he had discovered. It was his first telling of it, and Miss Newcomb enjoyed it immensely. He wanted very much to lean back in his chair, elegant and relaxed, and tell her all that he had seen and thought; and it was only with a great effort of will that he was able to recall himself to duty and, with Miss Newcomb’s aid, go through the months’ mail.

At four o’clock he stopped work and took Miss Newcomb in a taxi to her apartment, where he often stopped for a drink on his way home. Once outside the air conditioned office building, the suit seemed immediately to absorb the heat of the day, as if it were storing it up against the hard winter sure to come. There’s your Old World wisdom for you, he said to himself, smiling at the idea.

In the taxi, Miss Newcomb laid her hand on his. “Glad you’re back?”

“Oh, yes,” he said.

Miss Newcomb smiled and touched his padded shoulder with her forehead. “It’s a marvelous suit,” she said. “I adore it. I can’t make up my mind, though, whether you look like something absolutely wonderful left over from the ‘Thirties

He laughed and said, “Or . . . ?”

“ — Or an English colonel in mufti. But either way,” she said, “it’s great, great, great.”

“I’m very glad you like it.”

“Perfecto,” she said. It was one of her favorite words.

Simmons was amused by her language; it was part of her youthfulness, what made her so attractive. With Miss Newcomb beside him, her hand on his arm, and his own city presenting itself to his view, he felt a marvelous sense of certainty and power, here in this taxi which was one car and not a crazy amalgam, and driven by a man whose face was safely anonymous, not memorable and haunting, not a relic, not a souvenir of ugly history. Simmons banished the memory of the Spanish driver’s face; he touched the magical iron cloth of his suit; the thrill of it charged him with a feeling of boyish vigor and reminded him of a time when he was certain he would never die. He circled Miss Newcomb’s wrist with his thumb and forefinger. When they arrived at her apartment, the first thing he did was call Roberta and tell her he’d be late. He was always very good about this.

Simmons sent his suit to the cleaners, and when it came back he left it in its plastic bag to protect it from the soot. Every morning he saw it hanging in the closet. After a while, it seemed to him that he was really checking to see if it was still there. This notion amused him; he admitted to himself that the suit had taken on a kind of talismanic quality. And why not?, he asked himself, always tolerant of his own superstitions. It has brought me nothing but good luck, he said to himself; there hasn’t been a bad day since I bought it. Business was better than ever and his private life a joy. Even Roberta seemed happy.

He had noticed this within a week of their return: Her waiting look had turned to something more like fulfillment. It reminded him of their honeymoon. There was about her now that same air of surprise, gratitude, and shyness. He could tell by the way she touched him; it was her way of thanking him for something. He did not know what it could be. Perhaps she has faced reality at last and discovered an inner peace, he told himself; and he found this a satisfactory answer.

Breakfasts, however, were a bad time. She sat across the table from him, smiling, smiling as if there were some marvelous secret they shared. Perhaps, he thought, she is coming early to that time of her life. It would account for the odd way she smiled at him, and for the rather stunning nightgowns she had suddenly taken to wearing. and the pink silk robe she now wrapped herself in to drink coffee with him at eight in the morning.

“Kept ladies always wear pink silk robes,” she said, her smile full of secrets. “That is why I bought it.”

“It’s very pretty,” he said, after clearing his throat. He had hardly trusted himself to speak.

“Oh, you!” she said, and looked down shyly.

Also, some nights. before going to her room, she would come in to his, where he was working at some contract or estimate, and not kiss him good night in the ordinary way but would take off his reading glasses and kiss his temples and eyelids, and with her hand caressing the back of his head. It was a manner altogether new, and he was too astonished to be made anything but thoughtful by these attentions.

Then too, at these times, she would say disturbing things, such as, “My secret lover.” Or, “You, my dearest, my midnight visitor.” And, “Oh, you wild man, you.” Then she would put his glasses back on and, always, as she went through the door, would look back over her shoulder, coquettishly.

Clearly, a doctor’s advice was called for; but Simmons delayed, hoping this — what should it be called? — this seizure would work itself out and disappear as suddenly as it had come.

Apparently, in spite of her smiles and air of well-being. Roberta was having a hard time of it too; for whenever he awoke in the night he heard her rustling and pottering through the apartment. Several mornings each week she slept late. and when this happened he always found the evidence of her night prowling: an overflowing ashtray, a demitasse cup, and the thin, cylindrical espresso coffeepot she had bought in Madrid. And often, in the kitchen, he would find dirty dishes and crumbs on the plastic work surface, the mayonnaise jar with the lid off, and the scraps of a piece of meat which had been left over from dinner.

It was alarming, but he had Miss Newcomb for comfort and, after a while, found that she preferred him in the role of worried husband. She became very wifely.

Still, after a few months of this, he had to admit that Roberta seemed to be thriving, had put on weight — was beginning to look rather like the Spanish lady on the lid of the cigar box — and seemed to be very happy indeed. Once or twice he had even wakened in the night to hear her laughing in her sleep.

And it was precisely when he thought the situation well in hand, all cause for worry past, that he went to put on his Spanish suit one morning and discovered it was missing. “Oh, God!” he said, and had a vision of Roberta, scissors in hand, quite mad, cutting his suit to ribbons. With something close to frenzy he pushed his suits along the closet bar, one at a time, hoping he had simply overlooked it. But it was not there, it was not there. He sat down. I must be calm, he told himself. He was perspiring; he unbuttoned his shirt, one part of his mind thinking: I will have to shower again. He reached for a cigarette; the box on his desk was empty. He swore and went into the living room and found two still left in the alabaster box on the coffee table. There was the usual demitasse cup and ashtray heaped with ends, and now — and for some reason he took this as the final insulting blow — a dish with some bread crusts and tomato seeds floating in oil.

“One might as well be living with an Italian peasant!” he said — almost aloud, so fierce was his anger.

Then he sat down, and after a few puffs at his cigarette he felt calmer and thought perhaps Roberta had sent his suit to the cleaner. It was unlikely, but this was the only reasonable explanation he could come up with. Another thought then came to him, less reasonable but of such compelling urgency that he found himself on his feet and moving toward her room before the thought was even fully formed.

The door was ajar; he pushed it open slowly, not making a sound, and what he saw froze him into an even deeper stillness. Her nightgown, leaf green, lay on the floor at her bedside, insubstantial and shifting in the light breeze that blew through the window. Roberta, her face slightly swollen with sleep, was only half covered by the sheet. He had never seen her so desirable nor ever thought her capable of such an attitude of abandonment. Desire stirred within him, but he remembered his anger and opened her closet doors. His suit was on the first hanger, and, furious now, not caring how much noise he made, he savagely pulled it out from among her dresses. Roberta did not waken. He closed the bedroom door behind him. “Shameful!” he said, and shook his head.

Even the shower did not calm him; still angry, he punished himself with the towel. He said, “Yes, healthy appetite; getting fat, of course, but inside she is very sick!” He took this as a personal affront, as if by getting sick she had betrayed him. And how shall I get her to a doctor? he asked himself. Her doctor was a friend, Ted Myers. Simmons left a note for Roberta:

Haven’t seen the Myerses for long time. Why not invite them dinner Fri. night?

Roberta invited the Myerses and they, happily, were able to come. In his taxi on the East River Drive next morning — a time of day he had come to set aside for personal, as opposed to business, thoughts — he decided not to telephone Ted Myers but to let him come unaware that anything was going on. Doctors were like that, Simmons knew: If they were told to look for something, they were more than likely to find something. What he’d do, simply, was this: The day after the party he’d call Myers and ask him. Just spring it on him and get an educated reaction. Simmons wished that the psychiatrists would put out dream books like those he had read when he was a boy; then, he could simply look under the various headings — Suit, Closet, Wife — and get a line on the whole thing. He shrugged. Oh, they’re working in the dark, too, he told himself, recalling that Ted Myers had once said, “There are still some things at which we just have to throw up our hands.”

He leaned his head on the back of the seat and closed his eyes. He was tired; he had not slept well. In the beginning, Roberta’s night prowlings were as nearly silent as she could make them; lately, however, she had become quite brazen, and he was often wakened by the noise of clattering dishes and what sounded like books being dropped. He wondered if she was trying to let him know that she was disturbed. He groaned. The only comforting thought, really, was that the psychiatrists did not know very much either.

In fact, as it turned out, they knew even less than he thought; for, after an altogether unremarkable and even charming dinner party, Ted Myers said, as he was leaving, “Simmons, you’re a lucky man,” and he punched him lightly on the arm to show he meant that Simmons deserved his luck. And when the door was closed and Simmons turned and looked at his wife, he knew what Myers meant: She was beautiful. Or not beautiful, perhaps, but something even better: a beauty. She smiled at him then, in her altogether new style, and patted the sofa, inviting him to join her. He did so, transfixed, hypnotized almost, by this sudden new vision of her.

When he was halfway to her, she turned off the lamp; for a moment, before the light of the sky made itself felt, the room was completely dark, and he stopped, then continued toward her. Her arms were open for him; he saw the light on her bare shoulders, smelled the odor of her perfume, then felt her warmth.

“So glad they’ve gone,” she said. “I’ve been waiting all night to get my hands on you.”

His heart, that delicate member, responded in an alarming way. Roberta was so new to him; Miss Newcomb was now the familiar, the comforter. He felt a pang at the thought of her; it was betrayal, but he was sure she’d understand. Roberta was importunate, not to be put off; the intensity of her demand frightened him. “Mi vida,” she said. “Mi cielo.” To Simmons she seemed now as foreign as the words she was uttering. What had come over her? Was it Europe? It was said to have terrible effects on a certain kind of American.

Afterward, he sensed her disappointment, even though her voice was very gentle and what she said was clearly meant to be soothing. “You must be very tired, dearest.”

He agreed that this was so. “It’s been a rough week,” he said. “And I haven’t been sleeping well lately.”

“How awful. If I had known I would have spoken to Ted. He could have prescribed something for you. Why didn’t you tell me?”

“And have you,” he asked, and paused to clear his throat, “have you been sleeping well?”

He saw her shy smile. “Never better,” she whispered.

He moved away from her, to a chair, and lighted a cigarette; and realized then that he might as well have left the room. His presence seemed to be of no interest to her any longer. She was wholly engaged in looking at her body, silvery in that light. There was a fantastic pride in her face as she looked at herself. It seemed to Simmons she was taking joy in her own flesh; there was more than merely satisfaction in the way she raised each leg into the light and gazed at it. But she had not forgotten him; she turned on her side and held her hand out to him. “Give me a puff, dearest,” she said. When he leaned toward her he saw her eyes and the adoration that was all for him. She did not immediately take the cigarette, but first reached up and touched his face with her fingertips. He wondered at her ways.

She drew up her legs and locked her arms around them, hugging herself. “Go to bed, love,” she said, “and sleep well, and sleep late.”

He stood up at once. “You’ll catch cold there, Roberta.”

She stretched her legs again. “No, I’ll go to bed soon; I just want to enjoy this a little longer.”

Simmons slept very well that night. He woke toward morning. Not moving, he listened to the sounds: footsteps, dish drawn across table top, click of cup on saucer. Familiar now. Even reassuring. He thought of getting up, of going out of his room to confront this person. No, better not, he decided. Really, everything was quite perfect; it was a lovely arrangement. Simmons faced reality; he had always prided himself on his ability to do that. We complement each other, he told himself. We have our arrangement, Simmons said to himself; we’ve made our little deal. A great happiness surged through him. He had to stretch his body to contain it all. This was what he had worked for during those 15 solid years. “How good life is,” he said, and fell into a sleep as deep as death.

When Roberta came into his room it was almost noon. It had been years since he had slept so late. Not quite yet awake, trying to read his watch — could it be so late? — Roberta’s presence in the room — what was she carrying? — confused him and he felt angry and betrayed. This passed at once when he saw she was carrying a tray. She lowered it to his bedside table, then sat down beside him and poured the coffee. She unfolded a napkin for him, and while he sipped the coffee she tore off pieces of the buttered toast and fed him.

“You need your rest,” she said, “and you need nourishment, and you deserve the very best.”

He smiled.

She refilled his cup and, offering it to him, looked up shyly and said, “What fantastic strength you have, and what powers of recovery! Really, dearest, you astonished me.” Wide-eyed, she shook her head in mock censure and said, “You are such a boy!”

He tried to laugh.

“You really are,” she said.

He stared at her, unable to speak. She turned away and lowered her head, misunderstanding his penetrating look. “Oh, surely not!” she cried, laughing.

He laughed too and said, “No, no, I’m going to bathe now.”

She insisted on running the tub for him; and as if it were a long journey, she bent down and kissed him before leaving. Her pink robe fell open and she did not pull it together until she had stood up, and even then took her time about it.

Simmons listened to the water running in his tub, looked at the tray beside his bed. “Oh, yes,” he said, “this way is not bad at all.” He drew the blanket up to his chin, savoring the last minutes before rising. He lay there in his narrow, elegant bed, hands folded on his chest, eyes closed with the bliss of being alive.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now