On September 13, 1948, Margaret Chase Smith was elected to the Senate, making her the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress.

Smith was the first woman elected to the Senate on her own merit. Six women had served in the Senate before she arrived there in 1948 (including one who served for a single day), but each of her predecessors had been chosen to complete the term of a man, often their recently deceased husbands. This was how Smith herself entered politics, but not what kept her going.

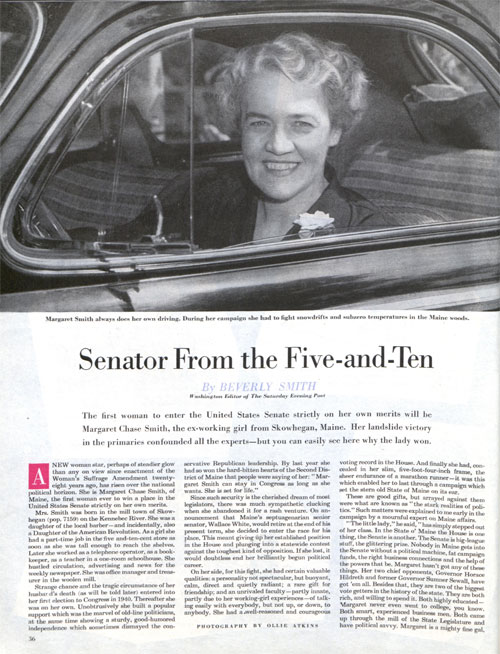

As the Post reported it in 1948 in “Senator from the Five-and-Ten,” her husband, Maine Congressman Clyde Smith, suffered a heart attack in 1940 just before filing for the upcoming primary election to run for a third term. His doctor advised him to have his politically savvy wife file instead. If Clyde got better, she could step down from the campaign, and he would replace her.

But Clyde Smith died soon afterward. In a special election, Margaret Smith was chosen to complete the remainder of his term, launching her political career as Maine’s newest Congressional representative. She won the general election the following September.

In 1947, Maine’s incumbent Senator Wallace White Jr. announced that he would retire when his term was over in 1948. Smith decided to run. In the Republican primary — which was tantamount to the election itself — she received more votes than the other three male candidates combined.

Her gender was not the only notable thing about Smith. In 1950, she publicly denounced Senator Joe McCarthy for promoting himself and silencing his critics by playing on America’s Cold War fears, four years before most of her colleagues did so. The Senate wouldn’t vote to censure him for behavior “contrary to senatorial traditions” until 1954.

Like her colleagues, Smith had initially been impressed when McCarthy first announced he had the names of hundreds of communist agents working in the federal government. He promoted the idea of a vast communist conspiracy within the country and himself as America’s best defense against it. Senator Smith challenged him to release the names, but he refused.

So on June 1, 1950, she delivered a Declaration of Conscience to her colleagues. Co-signed by six other moderate Republicans, it denounced McCarthy’s slandering and fearmongering, which he hid behind a façade of patriotism. She said:

I do not like the way the Senate has been made a rendezvous for vilification for selfish political gain at the sacrifice of individual reputations and national unity.

Those of us who shout the loudest about Americanism in making character assassinations are all too frequently those who, by our own words and acts, ignore some of the basic principles of Americanism: the right to criticize; the right to hold unpopular beliefs; the right to protest; the right to independent thought. The exercise of these rights should not cost one single American citizen his reputation or his right to a livelihood.

I don’t want to see the Republican Party ride to political victory on the Four Horsemen of Calumny—Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry, and Smear. … Surely we Republicans aren’t that desperate for victory.

Her declaration was not warmly received, and McCarthy soon took his revenge by removing Smith from the powerful Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. He also gave financial support to a Republican who unsuccessfully challenged Smith’s re-election. But Smith prevailed, retaining her Senate seat until 1973.

Smith is also remembered as the first woman to gather any noticeable support for a presidential bid in a major political party. In 1964, she announced her candidacy for the Republican nomination. Many Americans laughed at the idea. But President Kennedy took her candidacy seriously, telling reporters she would be a formidable opponent.

He probably remembered her voice raised against McCarthy years earlier. It was act of courage and integrity, two qualities Americans like in their presidents. And, as the financier Bernard Baruch said, if a man had delivered her Declaration of Conscience, “he would be the next president.”

Featured image: Photo by Ollie Atkins for “Senator from the Five-and-Ten,” from the September 11, 1948, issue of the Post.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This woman had a lot of guts, that’s for darn sure. We could certainly use her attributes today in a President—-man or woman. If we’d had Presidents all along comparable to her, our country (and the world) would be in considerably better shape!