In 1887, Arthur Conan Doyle unwittingly changed world literature. At the time, he was a struggling doctor, trying to build a practice and make a little money on the side. When his novel, A Study in Scarlet, was published, he launched the modern detective genre and set the standard that mystery stories follow to this day.

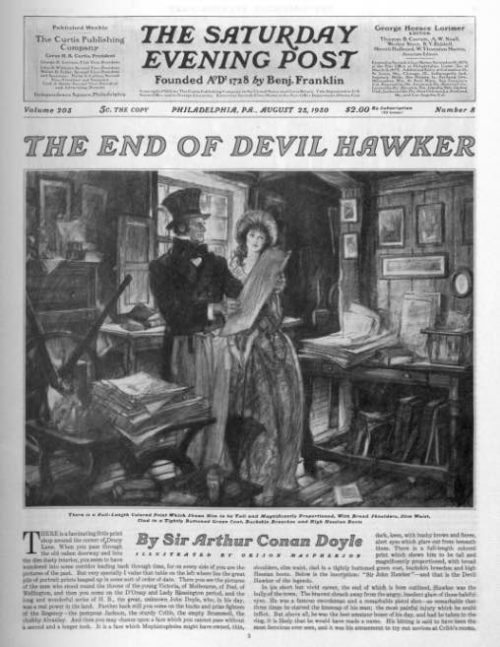

Conan Doyle of course had a long, rich career as a mystery writer. He even wrote several stories that debuted in The Saturday Evening Post, including “The End of Devil Hawker,” published in 1930.

For those who wish to follow in Conan Doyle’s footsteps, in 1920, Ronald Knox wrote these rules for a group of mystery writers to help them avoid plot tricks and clichés.

- 1. The criminal must be someone mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow.

- 2. All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

- 3. Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

- 4. No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

- 5. No Chinaman must figure in the story.

- 6. No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

- 7. The detective must not himself commit the crime.

- 8. The detective must not light on any clues which are not instantly produced for the inspection of the reader.

- 9. The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

- 10. Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

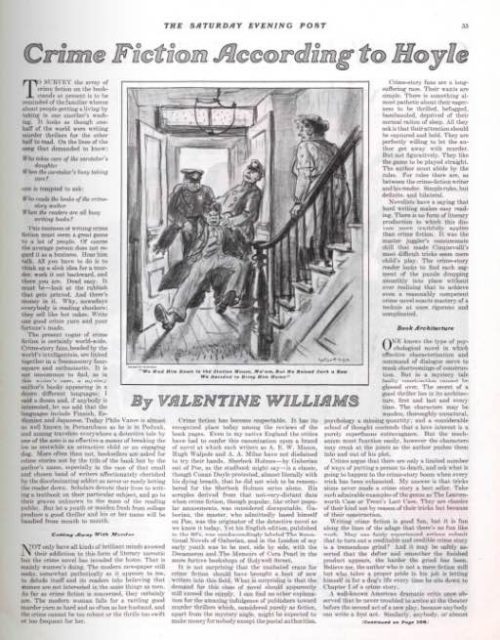

In 1931, another British mystery writer added a few more rules of “respectable” mystery writing. In “Crime Fiction According to Hoyle,” Valentine Williams — another mystery writer — emphasizes that readers want a well-paced plot that is plausible, suspenseful, and finishes with a surprise.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now