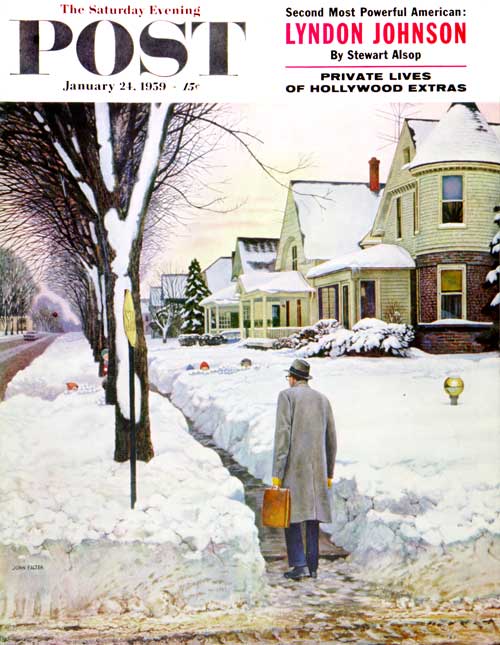

Cover Collection: Rockwell or Not?

Many of the covers of The Saturday Evening Post were painted by Norman Rockwell—322 in all—but not all of our covers were Rockwells! Can you tell which of these covers are Norman Rockwell originals and which aren’t? We’ve removed the artists’ signatures to make it more challenging. You can see the answers here.

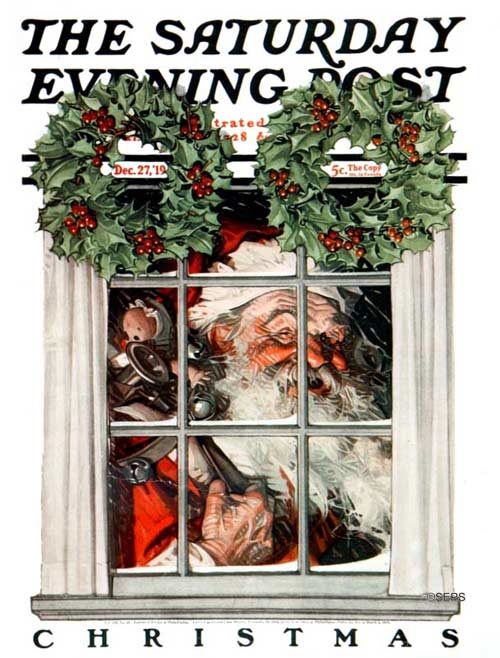

December 27, 1919

Click to Enlarge

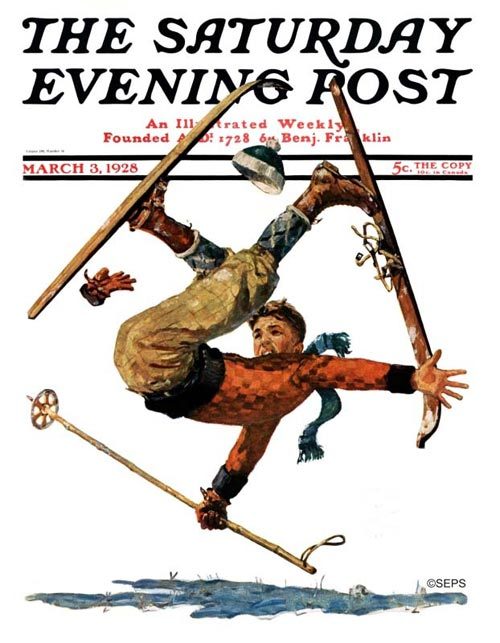

March 3, 1928

Click to Enlarge

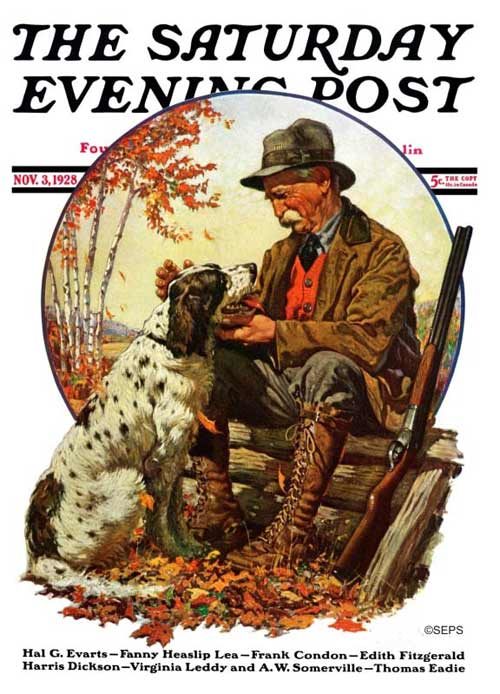

November 3, 1928

Click to Enlarge

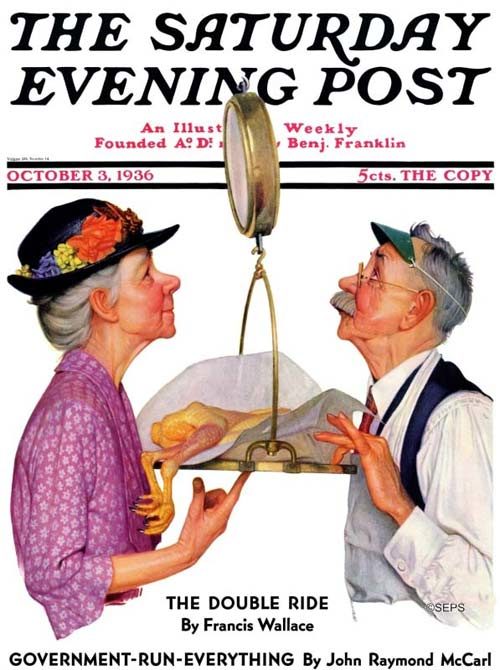

October 3, 1936

Click to Enlarge

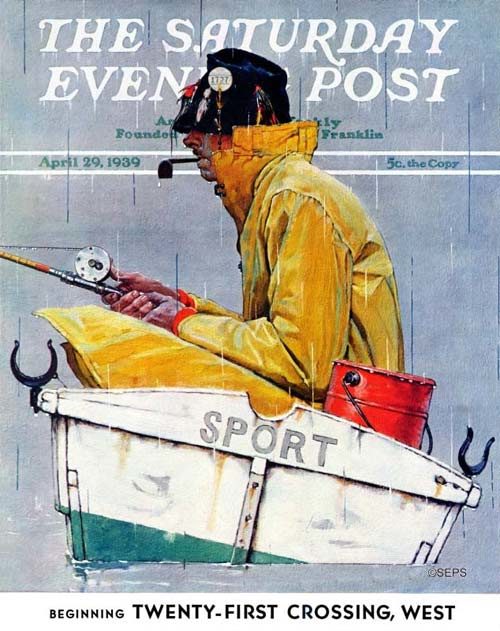

April 29, 1939

Click to Enlarge

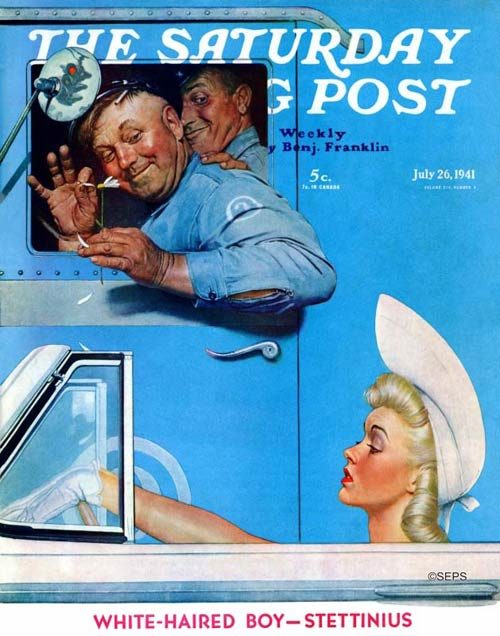

July 26, 1941

Click to Enlarge

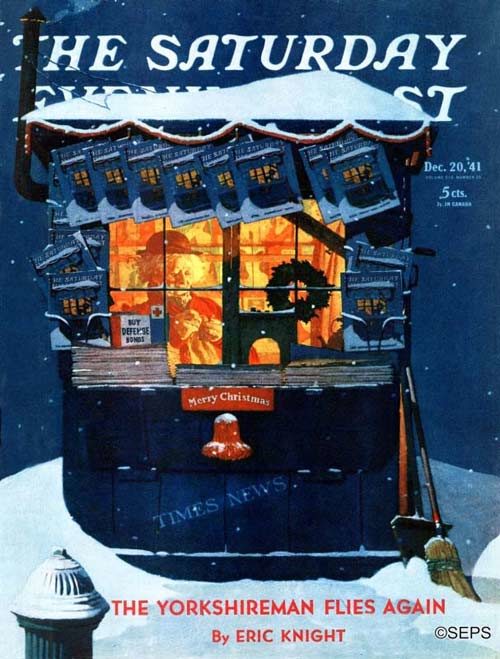

December 20, 1941

Click to Enlarge

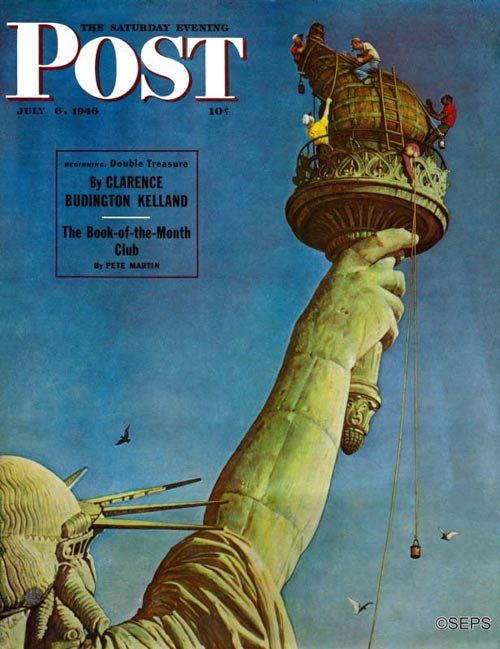

July 6, 1946

Click to Enlarge

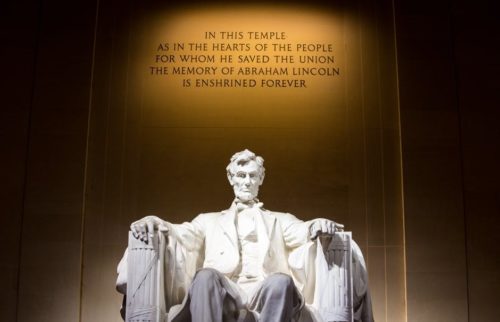

Answers to “Rockwell or Not?”

Here are the answers to the “Rockwell or Not” cover gallery.

- Santa Behind Window, December 27, 1919: J. C. Leyendecker

- Wipeout on Skis, March 3, 1928: Eugene Iverd

- Hunter and Spaniel, November 3, 1928: F. Kernan

- Tipping the Scales, October 3, 1936: Leslie Thrasher

- Sport, April 29, 1939: Norman Rockwell

- Two Flirts, July 26, 1941: Norman Rockwell

- Newsstand in the Snow, December 20, 1941: Norman Rockwell

- Working on the Statue of Liberty, July 6, 1946: Norman Rockwell

Con Watch: 6 Winter Olympics Scams

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Although the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea, are still more than a week away, criminals are already using this popular event to cheat people around the world. Once the games actually begin, the scams will only increase. Here are some Olympics-related scams you should be aware of:

1. Championship Check Cheaters. An email that appears to come from the United States Olympic Committee offers to pay you $350 a week to wrap your car with advertising for the Olympic Games and drive around town as usual.

Unsuspecting victims who respond to the email are sent a check for more than the amount to be paid. They are instructed to deposit the check into their bank account and wire the rest back to the company. Unfortunately, the check that the scammer sent was counterfeit. The money that was wired back to the scammer came right out of the victim’s bank account.

A check sent to you that is more than the amount you are owed and comes with a request for you to send back the overpayment amount is always a scam.

2. Gold-Medal Malware. Once the games are underway, many people will receive emails and text messages purporting to contain updates, photos, and videos of Olympic events. Unfortunately, if you click on links or download attachments sent by scammers, you will end up downloading either ransomware or malware that will steal information from your computer, laptop, tablet, or smartphone and use that information to steal your identity.

Trust me, you can’t trust anyone. Never click on any link or download any attachment unless you are absolutely sure it is legitimate. Even if the address of the sender appears legitimate, the address may have been “spoofed” to appear genuine. You are better off going directly on your own to sources that you know you can trust, such as www.espn.com or NBCOlympics.com, for up-to-date information, photos, and videos.

3. The Sponsor Spoof. It’s difficult to win any lottery, but it’s impossible to win one that you haven’t even entered. Emails that appear to be from Coca-Cola, McDonalds, or any of the other sponsors of the PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games tell the intended victims that they have just won a huge Olympics-related lottery. All the victim has to do to claim the multi-million-dollar prize is pay some administrative fees or income taxes. This scam is particularly insidious because, while it is true that lottery winnings are subject to income tax, no legitimate lottery collects income taxes on behalf of the IRS. They either deduct the taxes before awarding the prize, or they pay the entire prize to the winner who is then personally responsible for paying the taxes due on the winnings. And no legitimate lottery requires a winner to pay administrative fees.

4. Skating Away with Your Money. Olympics-related merchandise — particularly apparel — is extremely popular. Unfortunately, many websites are selling counterfeit and poor-quality Olympics apparel and other Olympics merchandise.

If you are interested in Team USA merchandise, go to the official Team USA website, where you can shop safely and securely. As always, whenever you shop online, you should use your credit card rather than your debit card because credit cards give you much greater consumer protection if your information is stolen.

5. Malware Slalom. Many people will be turning to apps for all manner of useful information about the Winter Olympics, and there are many legitimate apps available, including the official PyeongChang 2018 app, which is available at the Google Play Store and the iOS App Store. Unfortunately, many other Olympics-related apps appear genuine but are loaded with malware, including keystroke logging malware and ransomware. Many of these tainted apps are found on third-party websites. When downloading apps, stay with authorized stores such as the Google Play Store and the iOS App Store that try to screen for apps containing malware.

6. Social Media Snow Job. Scammers are also turning to social media such as Facebook to send out what purport to be links to photos and videos of amazing Olympic moments, but in truth download malware when the links are clicked. Again, the best course of action is to never click on a link unless you have verified that it is legitimate.

North Country Girl: Chapter 37 — Latin Lovers

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

After the fall semester finals, where I managed to squeak out a 78 in vile organic chemistry, I flew to Colorado Springs. I had hoped to do nothing but lie on the couch in my mom’s tiny apartment reading the dumbest romance novels I could find. But my Winter Break was spent prepping my anxiety-ridden mom for her upcoming Real Estate Agent exam (she was still waiting on that second marriage proposal), listening to one sister, Heidi, sob about how much she hated her school and every girl in it, and watching the other, Lani, pack her bags. She was moving back to Duluth to live with our dad. My mother mourned the loss of child support, but she would have gladly sent Lani to the moon to keep her away from her 21-year-old boyfriend. (Within six months, my dad signed some papers and Lani became a bride at sixteen.)

After two weeks of exhausting family drama, I flew back to waitressing, college, and full-on Minnesota winter, which meant no more riding my bike to and from work. I took the city bus to my job waitressing at Pracna, but the buses stopped running at midnight, forcing me to peel off my hard-earned ones for cab fare home, a cab that was always half an hour late; at one-thirty in the morning in Minneapolis there were probably all of three cabs on call.

Click to Enlarge

The January days ended at 4 o’clock, when the dim grey light of winter leached away. Most twilights found me hopping from one frozen foot to the other on the icy sidewalk waiting for the bus and feeling sorry for myself.

I was ignored by my roommate Liz, since I wasn’t fun anymore. Steve, my bad boy boyfriend, stopped calling, probably busy seducing freshman girls and selling bad pills to freshman boys. I looked at my roll of ones, shrunk down to almost nothing after buying plane tickets, paying for my winter tuition, and not working for the two weeks of Christmas break, and I wallowed in self-pity.

One night as I had my face pressed up against the foggy front window of Pracna, peering into the snowy frozen dark in search of my cab, I was rescued by a tap on the shoulder and a voice: “Hey you need a ride to campus?” It was Mindy, one of my favorite sister waitresses, who hustled me out to a car idling in front. Inside that toasty warm car were another Pracna waitress, Patti, and Patti’s very handsome Cuban boyfriend Eduardo, who was driving. Eduardo was at the bar almost every night, waiting for Patti and eyeing the asses of all the waitresses as we swerved around the tables. Mindy was smart, funny, and curvy, with dark, thick-lashed eyes and patent leather black hair. Her best friend Patti was a pretty, pale, flame-haired skinny girl, Lucy to Eduardo’s Ricky Ricardo.

Accepting the ride was not the bad decision. The bad decision was saying “Yeah, I guess so, for a minute” when asked if I wanted to hang out with them at Eduardo’s apartment. It was only a few blocks from my own underheated, creaky dump, where I had to let myself in on tiptoe so as to not wake either my roommate Liz or the crabby landlady beneath us. If I went home now, Mindy and Patti might think I was ungrateful or stuck-up, and I wanted them to like me.

A fancy new apartment building had popped up that fall near campus, in Dinkytown, a neighborhood known for cheap, code-violating housing. It towered like a supermodel over the crumbling duplexes and exhausted garden apartments the rest of us students lived in. I had heard that it was full of rich kids, but had never been inside.

This was where Eduardo lived. His apartment, which he had all to himself, was roomy and new, with shiny kitchen appliances, only slightly stained beige shag carpet, and plenty of heat. In the living room a ratty couch faced a littered coffee table; across the room sitting on shelves made of boards and bricks was the biggest, most complicated stereo system I had ever seen, and hundreds of vinyl records. I drooled a little.

Bob Marley crooned sweetly from out of the chest-high speakers, beers were cracked, joints were lit, and I felt a physical loosening in my chest and shoulders, which reminded me I needed to review the names of the bones in the human body for my physical anthropology class the next morning. One beer and I would go home. Maybe two.

Eduardo sat unnecessarily close to me, our hips touching, and in his charming accent said, “I apologize for my poor furnishings.” His father gave him a generous monthly allowance, which he preferred to spend on beer and pot and albums, rather than bookshelves (or books: I didn’t see a single one).

Eduardo’s family had managed to flee from Castro with quite a bit of their money. Although not nearly enough of it according to Eduardo, who held me captive for several more beers that night with his fascinating if slightly biased history of the Cuban Revolution as seen through the eyes of the very people who inspired Castro and Che to reach for their revolvers. Mindy and Patti, who had heard this tale countless times before, indulged in Pracna gossip till they passed out. Way too late, I finally thanked Eduardo and stumbled home through three-foot snowdrifts, thinking, well that was fun, I needed that, all work and no play and who wants to be dull? I promised myself once was enough, I wouldn’t make it a habit.

I ended up at Eduardo’s apartment the next night and the one after that.

Mindy, Patti, and Eduardo should have been a cautionary tale for me. All three of them were on academic probation after spending most of the fall semester listening to Bob Marley and smoking weed. Mindy was the only one who seemed concerned, but the textbooks she lugged to work and then to Eduardo’s and then back home remained uncracked. At least she bought books. Eduardo had better things to do with his money, keeping the four of us in Grain Belt beers and pot.

Eduardo wasn’t worried about being on probation. His family had just parked him at the University of Minnesota until he was old enough to join their mysterious business. If he flunked out, they would find a place for him at a college in Mexico or Spain, one that didn’t care about a transcript. Patti had decided that as the future Señora Eduardo, she didn’t need a college education either and rarely went to any of the three classes she had registered for.

Somehow I managed to keep my grades above water while doing what most 20-year-old college kids did then and still do: get shit-faced every single night. I just didn’t sleep much. I’d make it back to my dingy apartment and my disapproving roommate Liz in the morning in time to shower and change before trudging through the snow to my eight o’clock class. I told myself that as long as I never missed a class, I was fine. And I wasn’t spending my hard-earned money at an after hours club; I was just hanging out, in a warm place with very attractive people, while three little birds assured me that everything was going to be all right.

Eduardo was delighted to add a blonde to his collection; he was always stroking my hair, resting his hand on my thigh, holding a joint to my lips. I didn’t take it seriously, as Eduardo flirted with Mindy and all the other Pracna waitresses. Then one night, when my brain had punched out for the evening and Patti and Mindy had fallen asleep on the couch to the lullaby of “No Woman No Cry,” the handsome Eduardo took me by the hand and led me into his bedroom. The sex, even in my stoned and drunken state, was unremarkable, and I regretted it well before Eduardo rolled off of me and started snoring.

I have no excuse for my awful behavior outside of callow, stupid youth. I had broken the girlfriend code. I confessed to Patti the next day, as we were changing into our uniforms at work. I steeled myself for tears and yelling and the mass disapproval of the entire Pracna waitstaff, which thrived on gossip. What if I had to quit my job? Guilt and dread gripped my head and stomach in a vise but Patti shrugged it off as if I had done nothing worse than help myself to a beer from Eduardo’s fridge. She had absorbed enough of the Latin male mindset to know not to make a fuss about such a thing; she had her eye on the prize. Patti did ask me not to tell her best friend Mindy, and made sure that I never had another opportunity to be alone with Eduardo.

I was relieved and grateful that I had not been banished from Eduardo’s. I had grown to hate my charmless, chilly duplex. Liz and I lived directly above our witchy, man-hating landlady, who thundered up the stairs with her own key the moment she heard anything “suspicious,” threatening that if a boy as much as set foot on our front stoop Liz and I would be tossed out on the street where we belonged.

A brand new apartment with a cute shiny alcove kitchen in an elevator building with plenty of heat was all I needed of luxury, even though there was barely a stick of furniture besides the rumpled couch suffering from cigarette burns and many spilled drinks and that massive stereo system; in the bedroom a double mattress rested on the floor, with sheets that looked like they had never been changed, even after my escapade with Eduardo.

My drunken, stoned nights at Eduardo’s lifted me off the treadmill of work and school and the awfulness of trudging to both through the sleet, snow, and freezing temperatures of a Minnesota winter, a winter that set records in how high the drifts were and how low the thermometer plunged. Those three little birds had obviously never been through February in Minnesota.

I had thrown myself back into my hectic work schedule, taking as many shifts at Pracna as I could, closing up Saturday nights and ten hours later cheerfully serving Bloody Marys to people who worshiped at a bar. The church people arrived at one, still dressed in their Sunday best and ready for the weekend’s last bender.

Winter drives Minnesotans to drink, to search out the warmth of bars and other people, and Pracna, with the golden glow of its oak bar, polished by generations of elbows, profusion of fake Tiffany lamps bestowing flattering spots of color, and attractive and professionally friendly waitresses, was constantly packed. My shoebox stash was replenished and continued to grow, as fast as if the one dollar bills in there were mating and reproducing.

One snowy sub-zero day I was counting up my money like Scrooge McDuck and remembering that a year ago I was living on off-brand fish sticks and instant ice tea to scrape together the cash for a one-way plane ticket so I could spend six days in an old folks home in Daytona Beach.

Now my junior year Spring Break was coming up, and I was awash in dollar bills. I could go on a vacation that did not involve rooming houses or hitchhiking. My pal Liz had not mentioned any Spring Break plans of her own; we had gone our separate ways, passing at odd hours through our shared apartment, occasionally backing out of the already occupied bathroom, or silently sipping instant coffee in the morning. Patti was going to Florida with Eduardo to meet la familia. That left Mindy, who was dying to get away for a week somewhere your snot didn’t freeze the second you stepped outside, where you could wear sandals and a bikini, drink piña coladas, and meet boys. That sounded good to me too.

Mindy brought me brochures from a student travel company that offered Spring Break trips to Montego Bay or Acapulco, $299 for airfare and hotel. I voted for Jamaica. I had spent months listening to Bob Marley while smoking weed at Eduardo’s; I looked at the photo of a white sand beach and calm turquoise sea and pictured myself right there with a big blunt and a handsome Rastaman. But another Pracna waitress told Mindy that the beaches in Jamaica were overrun with packs of ferocious, tourist-eating dogs. Mindy was terrified of dogs; even my mother’s miniature poodle Shay-Shay would have sent her scrambling up a palm tree. So instead we flew off to Mexico on a chartered flight, packed with students who couldn’t wait to start drinking to wretched excess. Mindy and I navigated the flight and the bus to the hotel with only minor pawing and mauling from male Spring Breakers.

The bus disgorged us under a torn awning attached to a three-story, mildewy green building. Mindy and I stood on the sidewalk in the noon Acapulco heat, looked at the hotel and looked at each other. In no way did this hotel resemble the one in the brochure except for the name, which was La Casa Cheapo, or something similar. The sullen, non-English-speaking guy at the front desk glanced at our reservations and tossed us a big metal key attached to a heavy weight etched with our room number. The elevator doors opened to release a toxic combination of stinks and a pack of boys too hung over to even leer at the new meat. Our room did not overlook the famous Acapulco beach, but the busy, noisy Avenida Costera. The air conditioner, thick with dust, refused to work; when we opened the one tiny window clouds of car exhaust were sucked into our room. There was a urinal cake perched on top of the toilet. After emptying the drawers of roaches, we unpacked, put on our cute bikinis, and headed down to the pool, which looked like pea soup: a clot of vomit floated in one corner and two broken patio chairs in another. Mindy was about to cry. I was mentally comparing this dump to the luxury hotel my family had stayed at during a dental convention, and I snapped to a decision: “We’re going to the El Presidente.”

We rushed down the Avenida Costera to the El Presidente pool, which was exactly as I had remembered it from that trip, eight years before, the scene of so many drunken dental hijinks. Shiny sea blue tiles surrounded a huge, sparkling pool, with that eighth wonder of the world, a swim up bar. On all four sides of the pool area Tiki huts were serving oversized margaritas, frosty Sol beers, and drinks in coconuts. Rows and rows of lounge chairs held dozens of college students, boys and girls in various shades of Spring Break, from the just-arrived paper whites, to the should-have-gotten-out-of-the-sun crimsons, with a few lucky souls who can get a tan in seven days scattered about. Prominently displayed above this wonderland was a sign FOR GUESTS OF THE EL PRESIDENTE ONLY.

Mindy said, “If I have to go back to that hotel, I’m going home.” We agreed to live dangerously; if we had to, we could just spend the day getting thrown out of different hotel pools. We found two free lounge chairs and tried to look as if we belonged there.

Mindy and I were busy rubbing Coppertone on each other when two shadows fell over us. I looked up to see what was keeping the sun from bestowing some kind of glow to my pasty Nordic skin. There stood two Mexican guys, fully dressed in billowing shirts and tight pants. One looked like a younger, pudgier Cantinflas, smiley and slightly goofy. The other could have Eduardo’s taller, better-looking, older brother. He had dark brown, shoulder-length wavy hair and eyelashes longer and thicker than any offered by Maybelline; his gleaming white shirt gaped open to reveal a deeply tanned, muscular chest adorned with a thick gold chain and dangling charms: a small clenched fist in ivory, a blue eye, a half-dollar sized gold medallion. The guys asked if we wanted a drink (“Why yes, thank you!”) and introduced themselves. The tall one was Fito Giron—didn’t we recognize the famous singer? We had to have seen Fito’s poster in the hotel lobby! Fito was the star of the show at the El Presidente lounge; the other guy, the one who was doing all the talking, was Jorge, Fito’s full-time gofer and friend.

Rum and coconut drinks magically appeared and Fito scribbled on the bill offered by a fawning waiter. Mindy and I thanked Fito for our cocktails and apologized to Jorge for our ignorance. No, we hadn’t seen Fito’s act, we had only gotten to town that day. While Fito posed, hands on hips, chin cocked, hair tilted into the wind, Jorge insisted that we had to go that night to hear Fito. He, Jorge, would put us on the guest list. What were our names and room numbers?

Ten minutes trespassing and we were busted. We confessed that we weren’t staying at El Presidente but down the Avenida at the no-star hotel des estudiantes. This was shrugged off by Fito. “No importa,” he said as he looked down and locked eyes with me. Jorge was quick to jump in. “Don’t worry, your names will be on the list, you see Fito’s show and then we all go dancing!” Jorge wrote down our names, and Fito swooped down on me like a hawk to plant a kiss on both cheeks, then turned and left with a backward wave.

I was bewildered and amazed and giddy at what had just happened. We had landed dates in our first hour of Spring Break, we had free drinks in our hands, and we had successfully snuck into the El Presidente pool. To be sure that we were not at risk of getting the bum’s rush, we called over the waiter for more coconut rum drinks; he scurried over like a Mexican Groucho Marx, took our order, and let us know that everything was on Fito’s bill.

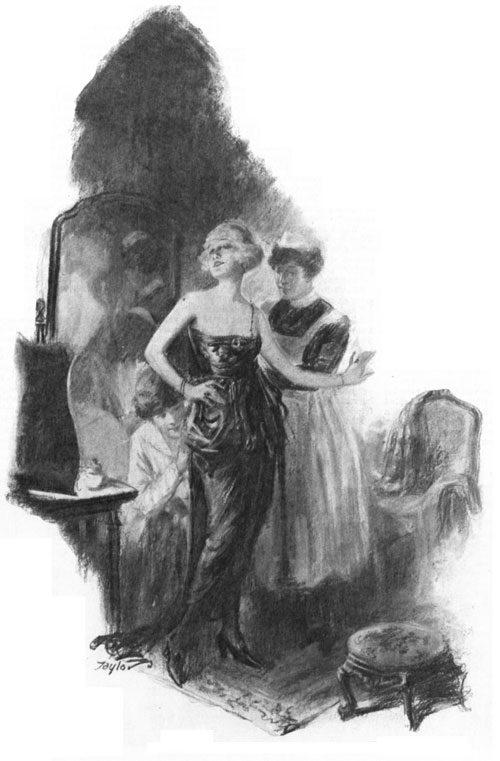

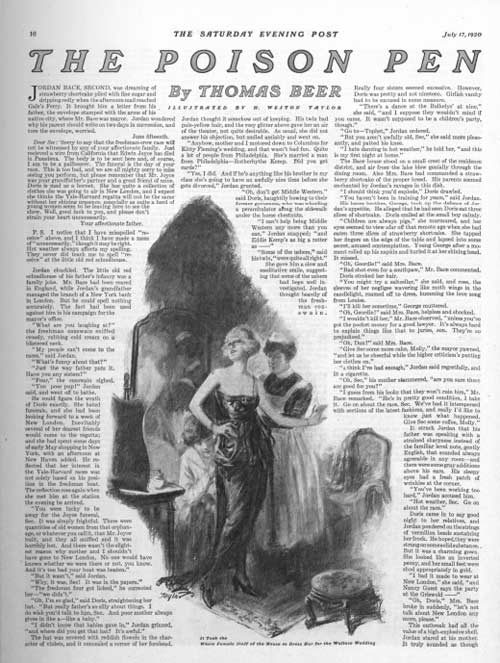

“The Poison Pen” by Thomas Beer

Jordan Bace, Second, was dreaming of strawberry shortcake piled with fine sugar and dripping redly when the afternoon mail reached Gale’s Ferry. It brought him a letter from his father, the envelope stamped with the arms of his native city, where Mr. Bace was mayor. Jordan wondered why his parent should write on two days in succession, and tore the envelope, worried.

June fifteenth.

Dear Sec: ‘Sorry to say that the freshman-crew race will not be witnessed by any of your affectionate family. Just recieved a wire from California that Edwin Joyce has died in Pasadena. The body is to be sent here and, of course, I am to be a pallbearer. The funeral is the day of your race. This is too bad, and we are all mighty sorry to miss seeing you perform, but please remember that Mr. Joyce was your grandfather’s partner and a great friend of mine. Doris is mad as a hornet. She has quite a collection of clothes she was going to air in New London, and I expect she thinks the Yale-Harvard regatta will not be the same without het shining presence, especially as quite a herd of young women seem to be leaving here to see the show. Well, good luck to you, and please don’t strain your heart unnecessarily.

Your affectionate father.

P.S. I notice that I have misspelled “receive” above, and I think I have made a mess of “unnecessarily,” though it may be right. Hot weather always affects my spelling. They never did teach me to spell “receive” at the little old red schoolhouse.

Jordan chuckled. The little old red schoolhouse of his father’s infancy was a family joke. Mr. Bane had been reared in England, while Jordan’s grandfather managed the branch of a New York bank in London. But he could spell nothing accurately. The fact had been used against him in his campaign for the mayor’s office.

“What are you laughing at?” the freshman coxswain sniffed crossly, rubbing cold cream on a blistered neck.

“My people can’t come to the races,” said Jordan.

“What’s funny about that?”

“Just the way father puts it. Have you any sisters?”

“Four,” the coxswain sighed.

“You poor pup!” Jordan said, and went off to bathe.

He could figure the wrath of Doris exactly. She hated funerals, and she had been looking forward to a week of New London. Inevitably several of her dearest friends would come to the regatta; and she had spent some days of early May shopping in New York, with an afternoon at New Haven added. He reflected that her interest in the Yale-Harvard races was not solely based on his position in the freshman boat. The reflection rose again when she met him at the station the evening he arrived.

“You were lucky to be away for the Joyce funeral, Sec. It was simply frightful. There were quantities of old women from that orphanage, or whatever you call it, that Mr. Joyce built, and they all sniffled and it was horribly hot. And there wasn’t the slightest reason why mother and I shouldn’t have gone to New London. No one would have known whether we were there or not, you know. And it’s too bad your boat was beaten.”

“But it wasn’t,” said Jordan.

“Why, it was, Sec! It was in the papers.”

“The freshman four got licked,” he corrected her — “we didn’t.”

“Oh, I’m so glad,” said Doris, straightening her hat. “But really father’s so silly about things. I do wish you’d talk to him, Sec. And poor mother always gives in like a — like a baby.”

“I didn’t know that babies gave in,” Jordan grinned, “and where did you get that hat? It’s awful.”

The hat was covered with reddish flowers in the character of violets, and it concealed a corner of her forehead. Jordan thought it somehow out of keeping. His twin had pale-yellow hair, and the rosy glitter above gave her an air of the theater, not quite desirable. As usual, she did not answer his objection, but smiled amiably and went on.

“Anyhow, mother and I motored down to Columbus for Kitty Fleming’s wedding, and that wasn’t bad fun. Quite a lot of people from Philadelphia. She’s married a man from Philadelphia — Rotherhythe Kemp. Did you get cards?”

“Yes, I did. And if he’s anything like his brother in my class she’s going to have an awfully nice time before she gets divorced,” Jordan grunted.

“Oh, don’t get Middle Western,” said Doris, haughtily bowing to their former governess, who was wheeling a perambulator along the sidewalk under the horse chestnuts.

“I can’t help being Middle Western any more than you can,” Jordan snapped; “and Eddie Kemp’s as big a rotter as —”

“Some of the ushers,” said his twin, “were quite all right.”

She gave him a slow and meditative smile, suggesting that some of the ushers had been well investigated. Jordan thought heavily of the freshman cox swain. Really four sisters seemed excessive. However, Doris was pretty and not nineteen. Girlish vanity had to be excused in some measure.

“There’s a dance at the Bulkelys’ at nine,” she said, “and I suppose they wouldn’t mind if you came. It wasn’t supposed to be a children’s party, though.”

“Go to — Tophet,” Jordan ordered.

“But you aren’t awfully old, Sec,” she said more pleasantly, and patted his knee.

“I hate dancing in hot weather,” he told her, “and this is my first night at home.”

The Bace house stood on a small crest of the residence district, and air from the lake blew genially through the dining room. Also Mrs. Bace had commanded a strawberry shortcake of the proper breed. His parents seemed enchanted by Jordan’s ravages in this dish.

“I should think you’d explode,” Doris drawled.

“You haven’t been in training for years,” said Jordan.

His lesser brother, George, took up the defense of Jordan’s appetite. He alleged that he had seen Doris eat three slices of shortcake. Doris smiled at the small boy calmly.

“Children are always pigs,” she murmured, and her eyes seemed to view afar off that remote age when she had eaten three slices of strawberry shortcake. She tapped her fingers on the edge of the table and lapsed into some secret, amused contemplation. Young George after a moment rolled up his napkin and hurled it at her shining head. It missed.

“Oh, Geordie!” said Mrs. Bace.

“Bad shot even for a southpaw,” Mr. Bace commented.

Doris stroked her hair.

“You might try a saltcellar,” she said, and rose, the sleeves of her negligee wavering like moth wings in the candlelight, roamed off to dress, humming the love song from Louise.

“I’ll kill her sometime,” George muttered.

“Oh, Geordie!” said Mrs. Bace, helpless and shocked.

“I wouldn’t kill her,” Mr. Bace observed, “unless you’ve got the pocket money for a good lawyer. It’s always hard to explain things like that to juries, son. They’re so prejudiced.”

“Oh, Dan!” said Mrs. Bace.

“Give Sec some more cake, Molly,” the mayor yawned, “and let us be cheerful while the higher criticism’s putting her clothes on.”

“I think I’ve had enough,” Jordan said regretfully, and lit a cigarette.

“Oh, Sec,” his mother stammered, “are you sure those are good for you?”

“I guess from his looks that they won’t ruin him,” Mr. Bace remarked. “He’s in pretty good condition, I take it. Go on about the race, Sec. We’ve had it interspersed with sections of the latest fashions, and really I’d like to know just what happened. Give Sec some coffee, Molly.”

It struck Jordan that his father was speaking with a strained sharpness instead of the familiar level note, gently English, that sounded always agreeable in any room — and there were some gray additions above his ears. His sleepy eyes had a fresh patch of wrinkles at the corner.

“You’ve been working too hard,” Jordan accused him.

“Hot weather, Sec. Go on about the race.”

Doris came in to say good night to her relatives, and Jordan pondered on the strings of vermilion beads sustaining her frock. He hoped, they were strung on some solid substance. But it was a charming gown. She looked like an inverted peony, and her small feet were shod appropriately in gold.

“I had it made to wear at New London,” she said, “and Nancy Guest says the party at the Griswold—”

“Oh, Doris,” Mrs. Bace broke in suddenly, “let’s not talk about New London any more, please.”

This outbreak had all the value of a high-explosive shell. Jordan stared at his mother. It truly sounded as though Doris had been talking too much of the missed race. It must be that. His twin was considering Mrs. Bace with a pained bewilderment.

“Oh, very well, dear. Any signs of Johnny?”

“His visibility is still low,” said Mr. Bace through his cigar smoke, “and that is a mighty pretty dress — frock. You look like the late Lola Montez a good deal.”

“Oh, Dan!” Mrs. Bace gasped, and pink touches appeared in her cheeks.

“Sure, I don’t know who Lola was,” said Doris kindly, “but it sounds like a slam. There’s Johnny. He always takes a bit off the rose bed. Good night.”

Jordan wondered if the best breeding permitted a young man to sound his horn outside the doors of a gentleman’s house summoning his daughter forth. He strolled over to the window and watched Doris flutter into the motor, where Johnny Rhodes was sprawled gracefully.

He had a natural admiration for young Rhodes, a great figure in white flannel, with a curly dark head that showed fully as the motor slipped under the lights of the dining room outflung on the gravel.

“If Doris marries that mucker,” said George, “I’m goin’ to run off.”

“Oh, Geordie!” Mrs. Bace moaned.

“That’ll do, son,” said Mr. Bace, and rose. “Well, I’ve got to go down to the club and blackball some men. Be back in an hour, Sec.”

When the family car had carried him off Jordan asked questions, having planted George over a volume of Gale’s Ferry snapshots. Mrs. Bace was never expansive.

“There’s been a lot of trouble with the police force, Sec, and it’s been dreadfully hot. It would have been such a rest for him to go East. It was too bad poor Mr. Joyce had to die just then and” — she flushed “and — really — Doris wasn’t very — very nice about missing the races. I suppose we should have found a chaperon for her and let her go. And there’s been some trouble at the bank with one of the tellers. And of course, dear, your father isn’t young.”

“I suppose Doris just simply raised hell.”

“Oh, Sec!”

“I’m sorry, mother. Look here, is she going to marry Johnny Rhodes?”

“I hope not,” said Mrs. Bace with more firmness than she usually mustered. “I’m sure I hope not, Sec.”

“Of course,” Jordan mused, “there’s his D. S. C. and all that, but — I hope she doesn’t. I don’t mind his being divorced, but —”

Jordan played golf considerably, and Johnny Rhodes had a clear, carrying voice in the country-club dressing rooms. His theories on matrimony and finance were memorable. Still he was jolly and handsome, and there was the medal. Jordan frowned.

“You and dad can put your feet down —”

“Oh, Sec, Doris is so old for eighteen!”

Jordan grinned and went off to talk to George. His brother illuminated the matter of Mr. Joyce’s funeral when they had gone to bed. He sat on Jordan’s floor and barked with the note of one long oppressed but now sure of a hearing.

“Sounded like a baseball game when everybody’s jumpin’ the umpire. She said dad was old-fashioned and stuffy and mid-Victorian and —”

“Oh, she’s got that mid-Victorian thing? Go on.”

George continued at some length, including his own grievances in the business of having his Navajo Indian headdress borrowed for the country-club masquerade in April and so lost.

“But Sid Conway says he’ll get his cousin in Arizona to get me another. Sid’s a peach, I think. He’s got a lot of sense too. He don’t hang round Doris the way he did.”

“That’s too bad,” said Jordan drowsily.

“It is not! Why, gee, you wouldn’t want a nice fellow to go and marry a thing like her? But how much does a coxswain have to weigh, huh?”

Jordan stirred somewhat when a motor rattled in the drive toward dawn, but he was deeply asleep when George shook him at ten.

“Get up, Sec! Say, something’s happened!”

“Dad isn’t sick?”

“No. He’s mad, though, and mamma’s cryin’, and — it’s some kind of something. Get up!”

George was inarticulate and clearly a little frightened. Jordan hauled on a dressing gown and trotted downstairs through the shuttered coolness of the wide house to the dining room. His sister’s voice detained him outside the door.

“Nonsense! I shan’t let you do anything of the sort. I’m not going to have a lot of cheap detectives and things mixed up in this. I —”

“I’m not going to have my daughter insulted through the —”

Doris laughed, not merrily.

“Of course, father, if you like publicity —”

“Oh, Doris!”

His mother’s open anguish brought Jordan into the room on the run. Mrs. Bace was still crying wearily. His father stood on the hearth slashing at the white flowers in the grate with a napkin. Doris was trying to tidy her hair with fingers that shook. “Some low hound has been writing your sister anonymous letters,” said Mr. Bace. “That’s what’s the matter, Sec. Look at it!”

“It’s a woman of course,” Doris alleged — “not a man. Do keep still, father.”

The letter was typed on a sheet of plain paper. Jordan read it hastily, wishing that his mother would stop crying.

Dear Doris: Really you are getting too much for a civilized community. That red hat you were wearing yesterday has given me a headache, and I am not quite well yet. No wonder your brother looked ashamed of you when you were bringing him up from the station. And when wearing red do remember that face powder should be used sparingly — if at all. The contrast is too marked. You had the effect of a rather ignorant chorus girl trying to look like a second-rate French actress.

As to the horrible thing you were wearing at the Bulkely dance last night, words fail me. Please understand that I have no objection to your going about half naked. It is being done, and the gown was no worse than some others there. But that cheap swagger of yours would be tolerable only in a raving beauty. If your idiotic father has not the sense to check you up it is time someone else did. Au revoir.

“I’m going to ring up the police head —”

“You’ll do nothing of the sort,” said Doris, cutting Mr. Race’s sentence neatly. “You told us yourself that things like that always leak out of the police office. And there’ll be reporters at the Conway tea. I’m not going to have them telling people some woman —”

“How d’you know it’s a woman?” Jordan asked.

“Oh, really, Sec, a man wouldn’t bother about clothes! And it’s all about clothes. Of course it’s a woman!”

“But the hat isn’t really red, darling,” said Mrs. Bace. “It’s a cerise — and do try to drink some coffee, dear. You mustn’t wear yourself out.”

“I’m not!”

Jordan looked at the torn envelope. It was postmarked from the city-hall station, and dated from yesterday of course. He found himself mastering a grin. But he effaced this, as his father was staring at him, and it would not do to smile over a letter in which Mr. Bace was called idiotic. “It’s a dirty trick,” he said, “and can’t the police —”

“Oh, don’t be childish!” cried his sister, and walked out of the room.

“It’s a damned outrage,” said the mayor, chewing his lip.

“Oh, Dan,” wailed Mrs. Bace, “do be calm! I mean — you can’t be calm, dear — but do eat something.”

Mr. Bace refused food and set off for his office. Jordan puzzled, drinking coffee.

“I didn’t like that hat an awful lot,” he said. “It’s rather loud. And that dress isn’t what you’d call quiet, mother. Of course girls wear things like that, but —”

And the facts did not at all excuse this piece of blackguardism. Jordan worked himself into a fair measure of wrath as the day progressed. His sister was his sister. He might find cause to criticize her privately, but no stranger should be allowed to. This must be some jealous woman of course. He seldom went to such dances as his years permitted. He prided himself on a disdain for gossip. He had never even fancied himself in love. Perhaps it was a duty to squire Doris about and note her rivals.

“I’ll come to this tea at the Conways’ if you want, mother.”

“Oh, you’re not asked, Sec. It’s for some English author — Sir John — who is it, darling?”

“Sir John Pelton, the one who wrote all those novels about Scotland. It’s a very grown-up tea, Sec,” Doris mentioned, wandering about the veranda.

“Read any of his novels?” growled Jordan.

“One or two.”

“I’ll bet against it,” said Jordan. “They aren’t fluffy stuff.”

“Oh, Sec!”

“What you need,” said Doris, “is a course in manners. You aren’t the only person in the family who reads, you know. I’ve got to dress.”

Mrs. Bace looked after her unhappily, and turned her pale face to Jordan when the click of heels had ceased.

“Doris does read, Sec.”

“Not enough to hurt her any,” he smiled.

“She’s very young, dear.”

“Hour older than me, isn’t she?”

“But you’re a boy,” said Mrs. Bace, settling the question. She patted him and went on: “And really girls don’t read as much as they did, or they read such odd things — Freud —”

“I see Doris wading into Freud,” Jordan choked.

His father did not go to the Conway tea, and came home wilted, late for dinner. Mrs. Bace fussed over him with suggestions of iced coffee and spoke almost sharply to the butler about the misguided electric fan. She was, Jordan thought, in an anguish of solicitudes.

Dinner embraced all the things Doris liked best, and George had been privately warned to keep his mouth shut. But Doris was cheerful.

“Sir John’s quite nice,” she said, “and not stiff at all. And his son got the Victoria Cross. I really like middle-aged Englishmen better than the young ones. They don’t seem to want to talk about themselves so much. Of course young men all do.”

“He did talk to you quite a long time,” Mrs. Bace nodded.

“What did he say about the Irish question?” Mr. Bace inquired.

“I didn’t ask him. Does he know anything about it?”

“He’s supposed to be something of an authority. He’s written three books on it, and so on.”

“Great Scott,” said Doris, “what a bore! Englishmen always seem to like politics. He asked me about some senator or other.”

“He must have learned a lot from you,” Jordan reflected.

Doris ate an almond and looked at her twin for a moment.

“I suppose you’ll grow up — if you ever do — to be a college professor or something. Why should a man want to learn anything when he’s talking to a girl?”

“Speech sometimes does imply an exchange of ideas, daughter,” said Mr. Bace mildly.

“Oh, Dan!”

“Thanks so much,” said Doris.

In the morning George appeared at Jordan’s bedside with news of more misery. But Mr. Bace had left before the morning mail arrived, and Doris was alone with her second letter.

“There weren’t more than fifty people at the Conways’ yesterday, and a lot of them were men. But this is worse. So silly too.”

She hummed while Jordan read the note she had received:

“Doris Darling: I am glad to note that the red hat was not on view yesterday. Still that orange suit was not all it should be. All right for a tennis tea and that sort of thing.

“You are clever about your ears too. I know how big they are, and the arrangement of the hair hides them very well indeed. The emerald ring was striking, but out of place.

“A reception for a literary celebrity, my girl, is not the same as a bride’s luncheon, you must remember.

“But what I principally complain of is that you monopolized Sir John for twenty minutes when there were many people three times your age and with twenty times your brain power waiting to talk to him. Moreover, it was rotten bad taste to ask if his son had been decorated. A glance at the headlines of yesterday’s paper would have informed you that his son was also killed in action.

“That fatheaded lunatic, your father, should make you read the papers. I suppose he is too busy grafting to pay any attention to you.

“God forbid that I should say a word against your mother. You have bullied her from the day of your birth, of course, and she is probably so cowed by this time that she does not dare lift her voice. I suppose, too, that she lets you dress like a cannibal queen because she had to dress on nothing a year as a girl. Clergymen’s daughters don’t get big allowances, do they?

“But she shouldn’t let you knock about with swine like Johnny Rhodes, dear. Yes, I know he’s fond of you. You probably remind him of Tottie Toothbrush, or whatever the name of that red-stocking blonde was that he married in 1912. Your mentality must make the same strong appeal to him. More later. I am sorry for your family, because the reaction to these little jabs at your self-conceit must affect them unpleasantly. I suppose you take it out on the servants too. So long.”

Doris hummed a moment when he had finished, and stared at him steadily.

“Mother’s gone down to talk to father. Really I didn’t think Sid Conway could be such a cad!”

“What on earth has Sid Conway got to do with this?”

“He was sitting on the window seat while I was talking to Sir John. That’s the only way — and we had a row in April. And, of course, he hates Johnny Rhodes.”

“I don’t think so. He’s always spoken mighty well of him, and they were in the same regiment. You’re wrong anyhow. Sid’s a gentleman.”

“He keeps giving me long lectures on — all sorts of things, and he’s just as stuffy and old school as father. It is Sid.”

“Junk!” said Jordan. “Sid wouldn’t say a word against dad anyhow, and he wouldn’t mention mother. It’s someone else. And did you talk to this Englishman twenty minutes? That’s where you let yourself in for it, sis. Who else was listening?”

“It is Sid — and if Sir John didn’t want to talk to me he could have left me. I want you to go and —”

Jordan flashed up into a queer anger. He was fond of Sid Conway, and no amount of evidence would make him swallow the accusation.

“Sid’s thirty nearly, and he’s known us all our lives. If he wanted to tell you what he thought of you he’d have done it out like a man. I shan’t go see him. Go see him yourself.”

“That’s pretty!”

Jordan was ashamed of himself promptly. Doris never wept. Now her eyes filled, and she looked at him across the breakfast flowers with a sort of fright. He pulled at the cord of his dressing gown.

“All right,” he mumbled, “I’ll go see him. But you’re all wrong.”

“You really like Sid, don’t you?”

“Of course I do.”

“Why is it men stick together so?”

“They have to. There are too many women loose round. We’ve got to protect ourselves.”

“You don’t talk so badly as you used to,” said Doris. She sat silent for a second, then flushed. “And I don’t take Johnny Rhodes seriously. That’s why this is so silly. It’s — it’s uncalled for, Sec. Give me the paper.”

Sidmuth Conway was a burly young man, who had taught Jordan how to use an air rifle ten years before, and still gave him good advice from time to time. He was amateur middleweight of the city. Jordan thought of this as he motored into the hot heart of town. The silly errand seemed likely to get him a lesson in boxing for which he had no wish or use. Sid, though, was patently glad to see him, and his expression was not guilty when he spoke of Doris.

“I was wondering if she’d be home tonight. No, there’s the Wallace wedding. Going?”

“I hate weddings,” said Jordan. “If you’d been a page as often as I wag! Are you going?”

“Not for love or money. Too hot. But I want to see Doris.”

Sid hesitated, rapping his pipe on his desk and blinking at the fan that wagged its revolutions from side to side.

“Fact is, Sec, I’m worried about Doris.”

“Are you?”

“Yes — like this: A girl can make an awful fool of herself without knowing it or meaning to — and she did yesterday. And, of course, she didn’t realize it — naturally.”

“I suppose no one does,” said Jordan.

“Of course not. Well, Sir John saw her and asked to be introduced. She was looking awfully pretty, and she started talking to him. They were sitting on the window seat, and a lot of people rather hung round, looking at the great man and all that. And, you know, her voice carries.”

“Like a freight car,” Jordan agreed.

“Anyhow, she said some things — it was rather funny, one way of looking at it — only it wasn’t. And after the party I motored him down to the club, and there were a lot of fools talking in the smoke room. Anyhow, it made me sore — and your father walked in to get some cigars. I’m afraid he heard some of it. But what I want you to — to think about telling her is that —”

“She shouldn’t make a fool of herself?”

“Oh, not so strong as that! But I don’t like hearing her get herself criticized any more than I would you, Sec.”

“Come and tell her so,” Jordan offered.

“Well,” Sid said, moving-in his chair, “we aren’t getting along very well just now; and you’re her brother — and I was thinking of writing her. Only that’s so idiotic, seeing that I live across the street, and all that.”

He waved his pipe to indicate assembled reasons. Jordan wiped his, forehead and beamed at Sidmuth.

“Do you write your letters or type them?” he asked with skillful yawns to suggest that the subject bored him.

“Type? I don’t know how. I’m like your dad. I’ve tried to learn and can’t. Fingers too stiff or something. But about Doris —”

With intricate guile Jordan discovered that Sid liked the peony dress and the cerise hat.

There wasn’t any flavor of dissimulation in the statements. Sid was plainly worried. The city was full of rank outsiders who envied the old families, and Mr. Bace was mayor on the reform ticket. Well, it was too bad that anyone should lift the smirk of criticism against Doris.

“And she jumps down your throat if you tell her her hat isn’t on straight,” Jordan nodded.

“It wasn’t her hat,” said Sid. “It was her paint at that fool masquerade after Easter. There was too much on her chin. Made her look as though she’d been eating raspberries and hadn’t wiped her mouth. Perhaps I didn’t put it right. I’m not much of a diplomat. But I’m a lot older than she is!”

“I don’t think it’s much of a game, being diplomatic with Doris,” Jordan told him. “Try a brick.”

“Rot! You’ve got to consider a girl’s feelings. I hadn’t any business to say all this to you, anyhow.”

“It’s just as well you did,” Jordan said darkly, and withdrew.

Sidmuth Conway, he felt, was guiltless; and any guilt attached to these letters was balanced somewhat by their tone of raillery. Doris let herself in for it. It was about time, he thought, that something was done to Doris. She did bully their mother. Her clothes alarmed him often, and her conceit was flourishing.

“You’re wrong about Sid,” he said curtly, “and I told you so.”

Doris was cutting the leaves of a novel. She looked at her twin sulkily.

“I suppose you went and said, ‘Hi, have you been writing Doris anonymous letters?’ And he said no, and that was all there was to it.”

“I didn’t do anything of the kind! And he likes that rotten dress too.”

“He would,” said Doris. “I hate the rag. It’s the wrong color. It’s what one gets for buying evening things by daylight.”

“You liked yourself pretty well in it the other night,” Jordan pointed out.

“Oh, stop talking like Geordie!” Doris cried, and threw the novel into a corner. She went on breathlessly to state that Jordan had no right to discuss her with Sid in any case, and finished with a thorough condemnation of the city from the street cleaning department to the architecture of the church they attended. “And, of course, father had to go and make us conspicuous by getting himself elected mayor.”

“You didn’t mind that when he was elected.”

“Do you think I’d be getting these beastly letters if he wasn’t mayor?”

“I think if you dressed like a human being, and didn’t try to hog all the men in town, you wouldn’t be getting anything but bills,” Jordan said hotly; “and don’t ask me to go snooping round to any more people asking fool questions either. No one ever named me Holmes.”

“I shan’t ask you to do anything else in a hurry, dear,” Doris hissed. “You’re as bad as father.”

“That’ll be all of that, please,” he retorted. “I notice that all you’re worried about in these letters is what this person says about you. Doesn’t seem to bother you having him — or her — call dad a fatheaded idiot and a grafter.”

“But that’s —”

“If you say that’s so I’ll just naturally kill you!” Jordan shouted.

“I wasn’t going to say anything of the sort. I was going to say that’s just as silly as the rest of it. And I don’t suppose you would care if I was killed,” she said with a waver of the voice that prophesied tears.

“I would though. I hate wearing black.”

“Ah,” she declared, “that’s the masculine sense of humor!”

Jordan began to reproach himself in an hour and came to terms. The girl was restless and pale. Mrs. Bace murmured over her all afternoon and the mayor brought home a box of the best chocolates to console her. But Doris was not in the mood for chocolates, and it took the whole female staff of the house to dress her for the Wallace wedding.

“Poor kid,” said Mr. Bace, “it’s very hard on her, Sec. She’s young, and she likes gay clothes and all that. It’s a cowardly sort of trick. Of course the police can’t do anything under the state laws unless the letters get scandalous.”

“I think calling you a grafter is pretty scandalous!”

Mr. Bace arranged his white tie and shook his head.

“Calling a mayor a grafter’s just ordinary repartee, Sec. See if you can trim this nail down for me, will you?”

The finger nail was broken a little from the edge, and the crack was blackened as if with coal dust.

“How did you do that, dad?”

“Blessed if I know. Run and order the car. It’s almost time to start.”

Jordan was proud of the family, setting off for the wedding. Doris looked well in white and silver. Mr. Bace carried evening dress splendidly, and of his mother Jordan was in no way critical. He wandered over to play dominoes with Sid Conway and spend the evening coolly. By his sister’s attitude, when she came home, he fancied a successful party. The next day was calm. The mail contained nothing odious and peace seemed planted in the house again. But Friday morning George — as scout — reported more trouble.

“Mother’s awfully mad this time,” he announced, “and father says he’s going straight to the police. Better hurry.”

“Oh, Sec,” said Mrs. Bace, “don’t get excited!”

“I want you to go down and stay in the post office all afternoon,” the mayor scowled. “I won’t have this sort of thing.”

“I think it’s really r-rather funny,” Doris said in a reduced tone, as though she spoke through veils. Jordan took the letter and his baked apple to the dining room window seat.

“Well, Doris, you are doing better. That white gown was all right, though the beauty spot on the right shoulder blade merely accented the fact of your skinniness and added nothing to your charms. And it was pleasant to see you shake hands with Mrs. Wallace as though you did not feel her far beneath you.

“Still you should not have told Mr. Wallace that Sec is too young for evening parties. Mr. Wallace has the bad taste to be fond of Sec, and is well aware that you are Sec’s twin. Sec, though an ass in some respects, is not all bad for a Bace. I don’t think he would have tried to talk about André Gide to that fat woman from New York without some idea as to whether Monsieur Gide is a dressmaker or a butcher.

“For your information I may tell you that the fat woman is writing a book on American education, and you will probably figure in it to your discredit. Beware of discussing foreign letters without reading them. It betrays a lack of common sense.

“And why apologize for your father’s job as mayor? True, he is no good at it, but that is characteristic of mayors. And as he has the misfortune to be your father, he is probably too worried by that responsibility to attend to his duties at the city hall very thoroughly. I suppose most of the missing funds for the new orphanage are on your back. It’s amazing that your mother’s hair hasn’t turned, and it is a pity that you will never be what she was. See you in church Sunday. Bye-bye.”

“He’s strong for you, mother,” said Jordan; “that’s one thing for him. What new orphan asylum is he talking about, dad?”

“I’m blessed if I knew there’d been any trouble with the fund. I’ll have to get hold of the charity commissioner and see.”

“And I do know who André Gide is,” said Doris. “I read some of that book about — about trees, or whatever it is. But you shan’t turn this over to the police, father. It — it isn’t very serious. It’s just some — some person with a poor sense of humor. And we’re going to Watch Hill next week anyhow.”

“He doesn’t seem to have an eye on Geordie,” Jordan chuckled.

“Oh, Sec,” said Mrs. Bace, “don’t — don’t speak of such a thing!”

After the morning bombshell Friday went peacefully. Doris decided to work in the rose garden, and after lunch Jordan saw her taking over an armful of blossoms to Mrs. Conway, whose flowers had suffered from some pest. This thoughtfulness was uncommon, and Jordan was touched. He pondered while driving George down to the dentist. Really this dose of critical advice was doing the girl some good. He somehow wished that the critic would supply him with notes on his own behavior. If he was in some respects an ass it would be quite as well to know them. The observer had hit his twin’s defects clearly.

He sat in the motor outside the office waiting for George and watched the people on the sidewalk about the Postal Building. Why, any one of them might be the traducer of his father! He shifted, frowning. Queer that the writer found nothing kind to say of Mr. Bace. Everyone liked him. Queer that his father didn’t resent it more keenly. A truly patient man, his father was — and Doris must be a fearful expense. Jordan rubbed his nose. Things were expensive. His own bill for haberdashery at New Haven was not small. Children cost a good deal, and Doris was never so grateful as she should be. She took things for granted. Jordan’s conscience wriggled uncomfortably. Well, at least he always said thanks, and his father seemed contented with him.

“Let’s go over and see if dad’s ready to go home,” George suggested, scrambling into the car.

The mayor’s outer office was empty except for the secretary.

“There isn’t anyone with him,” she said to the boys, “but he said he didn’t want to be disturbed. He had some mail to look through. Shall I go see if —”

Mr. Bace came .out of the inner office, hat in hand, as she spoke, and pinched George’s ear.

“I’ll be ready in a minute. I’ve got to run across the street for a second. Hang round. Don’t fool with the city property, Geordie.”

George began a conversation with the secretary, and Jordan strolled into the private office, a horrible place, decorated with oil portraits of earlier mayors and photographs of more recent sufferers in the cause of government. The furniture was built of high-polished redwood and carved with griffins and pine cones. Even the little typewriter stand had its sheathing of dusty gilt scrollwork. Jordan gave the municipal taste a shiver and walked to the window.

His father was plodding over the dull brick street in the simmer of heat toward the Postal Building. He was not long inside its brightly gleaming glass doors, but on the return a shabby man buttonholed him at the curb, and Jordan watched what must be the beginning of a long argument. Finally, he moved back to the typewriter table for a match and stood contemplating the machine. He had tried to use the one at the house occasionally, and now yawning with the delay he rolled a fragment of paper clumsily into the apparatus and pressed down a key. The businesslike click amused him. He wrote a line of random letters, then a key stuck and he patted it briskly with a finger. The nail snapped.

“Oh, the devil!” said Jordan, and reached for his pocket knife.

Afterward he thought that the key must be rather soiled. The crack had a thread of black along it. He was looking at this uneven edge in his bathroom before dinner, when it seemed that he had seen a nail broken so not long since. Where and on whom?

As he walked down to dinner he began to grin and had to stop outside the dining room door to adjust his face.

“Where’s Doris?” he asked.

“She’s stopped at the Conways’ for dinner,” said Mrs. Bace so cheerfully that Jordan laughed.

“The weather doesn’t affect you, Sec,” his father smiled.

“I’m all right. Are you coming on to Watch Hill with us, sir?”

“Not for a week or two.”

“I’d better stay here and keep you company.”

“Nonsense! Run along and keep cool, Sec.”

“I’d really like to stay here, sir. I could come down and be office boy.”

“I wouldn’t have you at the office for a million a day,” said Bace. “But you can stay if you want to, son. But do you want to?”

“Of course I do,” Jordan insisted honestly, “and that’ll get me out of helping straighten the cottage up. Doris’ll have to work.”

“Oh, Sec!”

“I’d like to see Doris workin’,” said George.

“You’re too ambitious,” Mr. Bace observed.

“Oh, Dan!” said Mrs. Bace.

Sunday church was hot, dull and restless. George wiggled aimlessly, and Doris glared at him across her father. Jordan looked about the scant congregation warily. There might be some noting eye upon them, and his father appeared to be asleep.

“That beast said he’d see me in church,” said Doris as they walked home, “and Sid wasn’t there. Of course I was wrong about Sid, anyhow — and I suppose I was horrid to you the other day, Sec.”

“Oh, that’s all right. And whoever it is can’t say anything about your clothes this trip.”

“Oh, yes he can,” she said miserably.

Under her veil her chin shook faintly, and Jordan hoped the next letter would be less acid. But on Monday morning she whirled into his bedroom while he was thinking of getting up and threw him a letter.

“I can’t stand that sort of thing, Sec. I don’t mind the rest of it, and — and I suppose some of my things are too — too but — oh, Sec, there isn’t a word of that true!”

She thrashed up and down the room, her rosy skirts fluttering and her hands clenched. Jordan rubbed his eyes and read.

“Doris, your Sunday get-up was perfect — just gaudy enough to show off your good points and not at all theatrical. The absence of powder was also pleasing. In time and with practice you may learn to go along unassisted by these little hints. Your inattention to the sermon was justified by its dullness. As to your attitude toward your kid brother, I thought it unnecessarily rude. Remember that George is only twelve, and therefore naturally wrigglesome.

“I wonder what you were thinking of most of the time? The extreme coolness with which you received Johnny Rhodes’ bow justifies me in the conclusion that you are bored with him.

“What does a young woman of your sort think about anyhow? Clothes and men and bank accounts, I fancy. I was wondering what would happen to you if your witless father happened to lose all he has stolen here and there and then drop dead. Probably you would expect Jordan to turn in and work for you. I can’t imagine you doing anything for yourself. You might make a competent housemaid with a little practice.

“After all, though, you are pretty safe. It must be satisfying to you to know that your father’s investments are solid and his life is insured for a pretty large sum. He looks worth about five or six years more if he does not land in state’s prison, and after that you will be very well fixed.

“They tell me you are off to the seashore soon. Heaven help your poor mother! I suppose she will have to sit about and watch you play the fool all summer. Well, dear, au revoir. We will meet soon again.”

“Pretty stiff,” said Jordan, discreetly scratching his chin.

“Look here, Sec, I can’t stand it! I don’t mind what they say about me. I don’t care, but I can’t stand it. I’ve never thought about father dying! I don’t care how much money he has! He’s always been so — so awfully kind to me — I —”

Her sobs began to hurt him. Jordan jumped out of bed and went to pat her back awkwardly.

“It isn’t fair,” he said. “It’s too bad.”

“And he isn’t well. I was thinking of that in church. He does look tired. It’s been a bad winter, and — I suppose there were too many parties. But I can’t stand this! Go and get Sid. He’s a lawyer. He knows all about things like detectives. I won’t have father called a thief! Some of the things about me are funny. But that isn’t, and I won’t stand it. I’ve got some birthday money left. Go get Sid, and — and if we can find who this is I — I want you to horsewhip him.”

“Good kid,” said Jordan.

“And don’t dare tell father about this — this thing!” She ripped the paper in her fingers. “I’d die if he thought anyone thought that I thought — oh, you know what I mean!”

Jordan gentled her up the hall into her own room, then went to his father’s quarters, where Mr. Bace was shaving.

“Doris wants me to get Sid Conway to hire detectives and all that.”

“’Nother letter?” said Mr. Bace sideways through his lather.

“Yes. This one’s perfectly rotten, and not a word of it true. It’s beastly. Doris,” Jordan muttered, “is an awful fool some ways, sir, but she isn’t — well, as bad as this letter makes her out, and she’s all busted up. She says if she can find the — the person that wrote it she wants me to horsewhip him.”

“Go ahead and retain Sid,” said his father. “Sid’s a good lawyer. All busted up, is she?”

“Into chunks, sir.”

“Poor old girl,” said Mr. Bace, and sighed.

Sid Conway and Doris had many consultations on the veranda before Mrs. Bace took her off to Watch Hill, and Jordan was left with his father in the empty house, where a flight of post cards from the departed daughter began to drift in on every mail.

“She writes a vile hand,” Mr. Bace said, studying one.

“She ought to learn the typewriter, sir.”

“Pretty hard, Sec.”

“Yes,” said Jordan, “and awfully hard on your nails.”

“Is it, son?”

“Awfully.”

Mr. Bace lit a cigarette and went on studying the last post card.

“She can’t write, but she spells decently, Sec.”

“I wonder,” said Jordan, “if she can spell things like ‘receive’ and ‘unnecessarily’ and all that?”

“Sure your allowance is big enough, Sec?”

“Of course, dad. Shoot you a game of pool?”

Your Weekly Checkup: Dealing with Hearing Loss

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

At a movie last night, my wife and I traded queries several times. “What did he say?” we’d ask each other. We’d heard the spoken words but they were uninterpretable sounds, failing to register meaningfully in our brains.

Hearing loss is a major cause of disability in the U.S., especially as the population ages. Approximately half of persons older than 60, and 80% of those older than 85, experience hearing loss severe enough to impact daily life. Impaired hearing is associated with increased rates of hospitalization, falls, dementia, depression, unemployment, lower income, and death. Annual health care costs for hearing impaired persons are considerably higher than for those with normal hearing. Hearing loss is the fourth leading cause of disability globally.

Hearing impairment can be of two types: conductive and sensorineural. Conductive hearing loss can result from simple wax build up in the ear canal or from more extreme conditions such as middle ear infection or fixation of bones in the middle ear (otosclerosis.) Medical or surgical treatment of conductive hearing loss often restores full hearing.

Sensorineural hearing loss results from cochlea (inner ear) dysfunction or damage to the cochlea’s nerves, caused by degenerative processes associated with aging, genetics, noise exposure, and drugs toxic to the ear, such as some antibiotics, chemotherapeutic or anti-inflammatory agents. Hearing loss can also be genetic, affecting about 1 in 1000 live births.

Hearing impairment in the adult (presbycusis) most often results from age and genetic related degenerative changes in the cochlea and the accumulated effects of exposure to noise and ototoxic drugs. It is usually bilateral, impacts higher frequencies, and reduces the ability to understand spoken words even if the sound is loud. My wife and I have this type.

Approximately 25% of U.S. adults have hearing loss from chronic exposure to loud noise. I often think of this when a car pulls alongside at a stop light with the radio blasting so loud I can hear it with the windows shut; or when people attend a concert with the sound amplifiers exploding; or ride for hours on a noise-shattering motorcycle. The blare damages delicate sensory hair cells of the inner ear that convert sound to neural signals for the brain to interpret. The damage can be temporary or permanent, depending on the extent of the noise exposure.

Hearing loss is also associated with smoking, diabetes, and obesity, suggesting that changes in blood vessels may play a role. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss, perhaps due to viral infection or a vascular or autoimmune event, is considered an emergency since steroids can be helpful in some instances.

For the hearing impaired, hearing aids can be useful, but often make spoken words louder, not necessarily more understandable. Cochlear implants can be used to bypass the impaired hair cells and electrically stimulate the auditory nerve.

Hearing is one of life’s critical functions. Protect yours by reducing contributing factors such as noise pollution and smoking. Consult an otolaryngologist for an evaluation if you have decreased hearing. Treatment can change your life.

My Wood Stove

We bought our first house 20 years ago, still live there, and will die there if we have any say in the matter, which I suppose makes it our last house, too. It’s not a perfect house — the kitchen, where we spend all our time, is on the north side of the house and doesn’t get much sunlight — but the house is otherwise suitable and fits us well. The best feature is the kitchen woodstove, which we fire up in fall and keep burning through late winter or until we run out of firewood, whichever comes first. Like most purchases I’ve made, it was impulsive but has given us more pleasure per dollar than anything we’ve owned.

I haven’t yet discerned whether we own the stove or it owns us. A man who heats his home with a woodstove has unwittingly signed up for a full-time job: cutting, hauling, and stacking firewood seven months of the year to stay warm the other five. Except for this man, since I hire a woman named Kelly to bring me firewood each fall. Kelly drives a school bus in our town and cuts firewood the rest of the year. It would be selfish of me to cut my own firewood when Kelly so obviously wants the work.

This still leaves plenty of work for me, carrying the firewood in from the fence row to stack on the back porch, waking early each morning to load the stove, tending it through the day, staring at the fire each evening contemplating matters great and small. Devoting one’s life to reflection can be tiring, and many evenings I fall asleep while staring at the fire, exhausted by my labors.

One of my favorite things to think about while seated by the fire is how much better the world would be if everyone were seated by a fire. While gazing at a fire, I’ve never thought ill of someone else or wished them harm in any way. Indeed, just the opposite has happened. A man I didn’t care for once appeared at our door on a winter’s evening. I invited him in and ushered him to a chair in front of the fire. We sat for a pleasant hour, philosophizing, and by the time he left, we were thick as thieves. The United Nations should have a woodstove instead of a dais.

Our stove was made in Norway by a company named Jøtul, which has been making stoves since 1853. If our woodstove had been made in China, I probably wouldn’t have bought it, but I liked the idea of it being built by Norwegians. I’m sure Chinese workers do just as good a job as Norwegian workers, so I don’t know why I feel the way I do. I don’t like what it says about me that I automatically assume Chinese workers are less devoted to quality. The Forbidden City Imperial Palace in Beijing was built in the early 1400s and is still standing. I’m fairly certain it wasn’t built by Norwegians. If it had been built in America, we’d have torn it down and put up a Walmart. This is the kind of thing I think about while seated by the fire.

I should probably mention that we have a second home, my wife’s ancestral farmhouse in southern Indiana. We put a Jøtul woodstove in it last spring, so now I can think down there, which has thrown my whole life out of whack since I go there for the express purpose of not thinking. Lately, I’ve been thinking that owning two houses with woodstoves is wearing me out, and I should sell one and live in the other. Except now I am a prisoner, bound by cords of memory to the first house where our children were reared, tied by marriage to the second, where my wife was raised. And so, come winter, I own and am owned, captor and captive alike, lighting one fire while dousing another.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and the author of 22 books, including the Harmony and Hope series featuring Sam Gardner.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

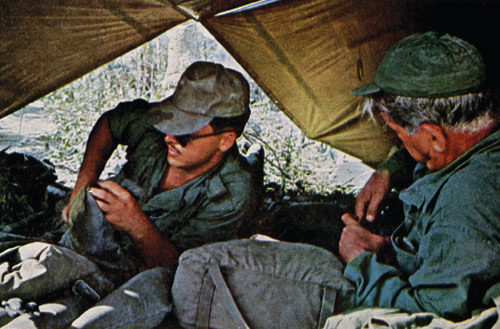

Heroes of Vietnam: My Son, the Soldier

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

—This article is excerpted from “My Son in Vietnam” by Harold H. Martin, originally published July 16, 1966, in the Post. The complete story as it appears in the original magazine is available at the end of this article. —

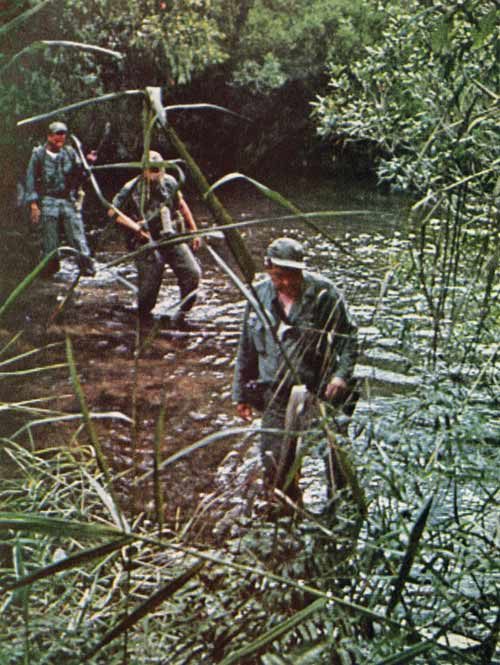

From San Francisco to Saigon, and from Saigon to An Khê, and now, on this rocky footpath leading under tall trees to his foxhole, I kept wondering what to say when I finally found him. Don’t get emotional, I kept telling myself. Don’t embarrass him in front of his friends. Play it cool. Say something flippant, like, “Private Martin, I presume,” or better still, just play it straight. Just say, “Hi, John, how’s it going?”

We came to the crest of a little rise, and Platoon Sgt. Zubrod, who was guiding me, stopped. “There he is,” he said. Thirty yards ahead, three troopers stood around a little fire, drying their rain-soaked shirts. For a moment I didn’t recognize him. From babyhood he had always been a chubby guy, built solid, like a brick. Now he was lean as a summertime rabbit, burned black by the sun. He wore a thin black moustache and dark glasses, and his hair, cut short, was curly.

We were very close before he looked up and saw me. “Good Goddlemighty!” he said. “What the hell are you doing here?” He stuck out his hand.

“I was in Saigon,” I said, “but they kept shooting up the place, so I thought I’d better come up here, where it’s safer.”

He grinned and poked me in the stomach. “What’s with the pot? I had a letter from Mama saying Hollywood was after you for Moby-Dick. They want you to play the whale.”

Suddenly he remembered his manners. “Excuse me,” he said. “Dad, this is David Crosby. He’s on the machine gun with me. And this is Robert Ellsworth. He’s in the next hole, on the 90 mm recoilless. Dave … Bob, the vision you see before you is my father.” He nodded toward the huge platoon sergeant standing beside me. “I see you’ve already met the Papa Bear.”

Sgt. Zubrod grinned. “You got everything you need?” he asked me. “Okay, I’ll get on back to the C.P.” With a walk that was remarkably bearlike, he set off down the trail to the log-and-sand-bagged bunker that was, at the moment, the command post of the outfit I’d come across the world to find — the 1st Platoon of Bravo Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) — now deployed 11,000 miles from its home at Fort Benning, Georgia, at a place called An Khê in the central highlands of South Vietnam.

Darkness was coming. We stood on the flanks of a gentle slope; behind us, the rising ground was covered with a thin forest of slim, white-barked trees, with an underlayer of low, thick scrub. Before us, down the slope, was the raw slash of the defense perimeter, 400 feet wide, that encircled the huge cavalry encampment. It was called the Green Line, but there was nothing green about it. Every tree and bush had been cut and burned, and the rough land smoothed off so a crawling man could find no defilade. It was a formidable barrier-in-depth of barbed wire — five rows of great loose rolls of concertina wire fastened to stakes — and between the rows of wire had been planted various explosive devices.

Fifty yards back from the nearest wire were high watchtowers, 30 of them in the 18-mile circuit of the camp. They were manned by machine gunners during the day, and at night by specialists operating sensitive watching and listening instruments. Between the watchtowers were the sandbagged gun pits where riflemen, machine gunners, and grenadiers stood guard from dark till dawn. Back of them, in the woods, were the mortar batteries, and back of the mortars the 105s and the 155s and the big 175s that throw a 400-pound projectile more than 20 miles, and behind them — on a field called the Golf Course — were the helipads where the gun ships stay on call. At the center, protected by all this bristle of guns and wire and minefields, was 1st Cav headquarters — the hospitals, supply dumps, chow halls, chapels, and office tents of division command.

In the other direction, beyond the wire, lay Viet Cong country — swamps and high grass and thin forest land of pine and palm trees where, until a few months ago, “Charley,” the Viet Cong, prowled at will. Now our patrols traversed it by day and set ambushes beside its trails and clearings at night. Far out, 4 miles beyond the wire, was a picket line of scattered outposts, lightly manned but able to bring down flare ships, gun ships, and artillery fire on Charley the moment he was spotted.

The Green Line was a barrier behind which the 1st Cavalry could stay forever, if it chose. From here it could fly its battalions out to harass Charley wherever he might be hiding in the hills, and bring them back to rest and refit in safety. High on the flank of Nui Hon Chu’o’ng, a mountain rising in the center of the encampment, was the mark of permanence — a huge black horse’s head on a yellow field — the shoulder patch of the division done in concrete. It was visible for miles, a defiant challenge to Charley.