This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

Everything was quiet in Camp Nam Ðông as I finished my round of the inner perimeter that night. I went up to the mess hall to check the guard roster. My watch said 2:26 a.m. At that moment the roof erupted in a blinding brilliance. The roaring concussion knocked me back through the door.

I scrambled into the command post next door. Master Sgt. Gabriel Ralph Alamo, my team sergeant, was already on the phone to Staff Sgt. Keith Daniels in the communications room, calling for a flare plane.

Now more mortar rounds rocked the camp. Grenades burst in volleys, their sound lighter than the mortars’ thunderclaps. Small arms and automatic weapons rattled from all sides. The mess hall was blazing.

When the blast of the first mortar round jolted Daniels out of bed, he flicked on the radio. Bare to the waist, Dan strapped on his holster but kept the gun in his hand, cocked, and watched the door, waiting to get a tone on the radio transmitter.

The minute he did, he sent his message: “Hello, Ða Năng … Nam Ðông calling … I have an operation-immediate message.”

“Roger. Roger. Go ahead, Nam Ðông.”

“Request flare ship and an air strike … We are under heavy mortar fire.”

The crashing, rending blasts of the mortar shells walked closer. A direct hit exploded on the supply room next door. Dan reckoned the communications room was next. Holstering his .45, he picked up his rifle, grabbed a belt of ammunition, and raced out the door.

Behind him, the communications room blew up. Already the whole long house was burning, flames crackling in the dry thatch of the roof and along the rattan walls.

We had known that the Viet Cong might attack at almost any time. But that weekend, the threat of attack seemed to have become much greater.

Close to the borders of both Laos and North Vietnam, Camp Nam Ðông had been set up to give some protection from the communists to the 5,000 inhabitants of the nine villages in our valley. To provide this protection, the camp commander, Ðai-uy (Captain) Lich, had a force of 311 Vietnamese.

The Special Forces detachment I commanded had been assigned as advisors to the camp commander — to give some protection and, even more important, to aid the villagers. Recently, for example, our medics, easygoing Sgt. Thomas L. Gregg and husky young Sgt. Terrance D. Terrin, had successfully handled an epidemic of encephalitis — “sleeping sickness.” Besides the 12 of us in Team A-726, there were only two other Westerners in the camp: Kevin Conway, an Australian warrant officer, and Dr. Gerald C. Hickey, an American expert on the Vietnamese mountain tribes.

On Saturday night, Sgt. Michael Disser, patrolling the villages farthest up the valley with a squad of night fighters, had radioed: “The villagers are scared, but they won’t tell me or my interpreters why.” Terry Terrin reported that his men had found the bodies of two murdered village chiefs. And tempers in the camp had flared in a quarrel — fomented by communist agents, I felt sure — between the South Vietnamese strike forces and our contingent of 60 Nungs, the tough mercenaries, ethnically Chinese.

I think that all of us in the team had a sense of foreboding that night — Staff Sgt. Merwin “Woody” Woods, I later discovered, wrote his wife: “All hell is going to break loose here before the night is over.”

At the blast of the first enemy mortar shell, Gregg rolled out of his bed in the dispensary, picked up his shotgun, and stepped outside.

The burning mess hall cast an eerie, dancing light over the camp, spectacular now with swirling smoke and the flashes of exploding shells. The V.C. mortars were zeroed in on us.

In the glare of the fire, Gregg saw crouched figures moving forward, not more than 20 yards away. He raised his shotgun and fired. The blasts caught six V.C. almost point blank. Gregg took a quick look around, then rushed back to the burning dispensary to save as much equipment as he could.

Racing to man his 81 mm mortar position near the dispensary, Sgt. 1st Class Thurman R. Brown pulled up short when he suddenly saw grenades arcing toward him from the direction of his own mortar pit. There, at the top of the concrete bunker at the rear of the pit, were at least two V.C. grenadiers. A 57 mm shell slammed into the wall a few feet away, blowing the wall apart and hurling Brown through the air. He ran to the C.P. to get some hand grenades.

By then the C.P. was burning. Alamo and I were trying to save what we could of the ammunition, arms, radios, and other equipment we had stored there. Brown grabbed a supply of grenades and headed back toward his position. A few yards ahead of him, one of the Vietnamese interpreters, George Tuan, was hit. Brown ran to Tuan, who was struggling to sit up. Both legs were off just below the knees. In 30 seconds he was dead.

Brown doubled back and ran through the burning buildings. A mortar shell landed right behind him, and he went flying through the air again. Stunned, he shook his head clear and glanced toward his mortar pit. Nobody in sight. He dashed over and jumped in. But when he looked up, he found himself staring down the barrel of a submachine gun held by one of two V.C. lying on top of his ammunition bunker. He raised his rifle, but the men rolled out of sight. Brown leaped to the edge of the pit and shot them both.

Back in the pit, he peered inside the bunker. Two Nungs were there. They couldn’t get out, and the V.C. couldn’t get in. The men Brown had killed had been about to blow up the bunker.

“Illumination rounds!” Brown ordered. The flares, floating overhead, would light up the area until the flare ship flew over.

As Brown started across the few feet between the bunker and his mortar, another burst hit. He tumbled through the bunker door.

When he tried to get up, he found he couldn’t move. His right leg felt dead. “Oh, Lord,” he mumbled. “I’ve lost a leg.”

Then he discovered he was sitting on it. In 30 seconds he was up and firing the mortar. As fast as he could move, he fired for illumination, bathing the scene in light so we could see the attackers.

Brown had awakened, seen a man die, helped fight a fire, survived four brushes with death, killed two men, and given us a fighting chance with his illuminating shells. All in five minutes.

Pop Alamo and I were still hauling stuff out of the burning C.P. when I saw Sgt. 1st Class Vernon Beeson running toward us. Mortar shells and grenades exploded within 25 feet of him, but nothing touched him. He took off through the burning buildings to his 81 mm mortar position. His Nungs were already there, breaking out ammunition. Bee knew that what we wanted was light.

“Gimme illumination!” he cried, and started firing as fast as he could drop the shells into the big tube.

Only 10 minutes had passed since the first V.C. shell landed.

From his quarters, Woody had seen that first shell explode — a ball of burning white phosphorus with “14,000 different-colored flames shooting out of it.”

Rolling off his bunk, he thumped to the floor, grabbing his .38 Smith & Wesson Special. Bullets were buzzing through the room. Woods reached up to his gun peg and took down his AR-15. Wearing only his GI drawers and pistol belt, he started crawling out the door to his mortar pit. The rocks outside were too rough on his knees, so he stood up and ran barefoot through the enemy fire to his position overlooking the helicopter pad.

The mortar on the other side of the gate was Mike Disser’s. Mike and Staff Sgt. Raymond “Whit” Whitsell, the team’s engineers, had elected not to waste time unlocking the door of the supply room where they slept. They left by the window, only moments before the room took a direct hit.

Whit scurried down the concrete steps into his 60 mm mortar pit. In easy reach, where he had laid them out as a precaution, were 18 rounds of illuminating shells. He plunked them in as fast as he could move.

The situation in Mike Disser’s pit was quite different. When he reached it, he found that six Nungs had preceded him, and that they were firing their carbines in the direction of the camp’s main ammunition bunkers. Then he peered over the rim of his pit. By the light of his flare, he saw what he has since called the most frightening sight of his life.

Hundreds of men were moving in on the camp. They were the main assault force of the two reinforced V.C. battalions — 800 to 900 guerrillas — that had ringed Camp Nam Ðông in the night. The first wave had overrun Strike Force Company 122 and was now less than 30 yards away.

Kneeling by his mortar and firing into the attackers as fast as he could, Mike glanced over his shoulder and saw Australian Warrant Officer Kevin Conway suddenly pitch headlong down the steps. He rolled over and Mike saw the wound. It was neat and round, smaller than a dime, almost exactly between the eyes. Conway was unconscious but alive. He moaned with each shallow breath.

By this time, Team Sgt. Alamo, painfully burned from the collapsing C.P., had dashed to Mike’s mortar pit through a hail of fire. When Conway fell, Alamo was at the front of the pit, picking off V.C. a few yards away with his AR-15. A few minutes later, a one-man army in the person of my executive officer, Lt. Jay Olejniczak (always called “Lieutenant O,” naturally), joined them.

Conway was sprawled in the dirt near the steps on the right of the pit when Jay got there. Alamo was in front of him, firing at figures flitting among the three ammunition bunkers 33 yards away. Disser, with his AR-15 cradled in his arms, was uncasing illuminating rounds and launching them in a steady, unfrenzied rhythm.

Jay took off his jacket and pillowed it under Conway’s head. A half-hour after he was hit, Conway quietly died. Jay joined Alamo at the parapet. With his M-79 launcher pointed almost straight up, he arched grenades among the ammunition bunkers.

Doc Hickey had decided to make for the dispensary, at the rear of the camp. When a mortar burst tossed him high in the air, he calmly felt himself all over for blood or broken bones; finding none, he continued on his way.

In the brief time of battle so far, I had been fully occupied with the need to save equipment we would need to fight with. Now I had to locate my men and organize the camp’s defenses.

In the flickering light from the fire, I saw movement at the gate, 20 yards away. “Mike!” I yelled. “Illuminate the main gate.”

He popped one over there and I saw three V.C. already within the inner perimeter. I squeezed off a half-dozen rounds. Two of the V.C. slumped. The third started crawling into the grass. I threw a grenade and he stopped.

Somewhere along the line I had been hit. My left forearm was bleeding, and there was a shrapnel wound about the size of a quarter in my stomach. It was belt-high, on the left side, and it was bleeding. But nothing hurt too much, and my legs were okay.

Nearby, Brown and his two Nungs were operating with precision. As quick as they handed him the 81 mm projectiles, he pulled off all the increment charges from the tail assembly — no need for boosters at that point-blank range — removed the safety clip, set the timing, and popped the shell into the muzzle of his mortar.

“Cover me,” Brown said to Dan. “They’re coming over the fence.”

A dead V.C. hung on the barbed wire of the inner-perimeter fence about 10 feet away. Brown had shot him only minutes before. Muzzle flashes and shouts indicated a cluster of V.C., perhaps 30 yards away. They seemed to be grouping for a charge.

An illuminating round lit up the scene. At least a hundred men were out there. One group of 10 or 15 made for the fence in a line of skirmishers. Dan fired fast with his AR-15. A couple of Nungs entered the pit and joined him at the rim. To his left, Dan heard the roar of a shotgun. He gave a quick look and saw, with relief, that Gregg had come into the pit too, and was booming away at anything that moved. Together they knocked down the first wave. But another came on, and another, and another.

The Nung alongside Dan let out a yell, wheeled and fired three quick carbine bursts at the top of the bunker in the rear of the pit. Dan turned in time to see a V.C. there, crumpling backward, a dynamite grenade in his hand.

Working my way to the rear of camp, I yelled for a medic and was rewarded with a shout from Gregg in Brown’s pit. I jumped in. Smiley, carrying the hand radio, followed.

“Did you call Ða Năng?” I asked Dan. He said he had. I couldn’t understand where the reaction forces were. We had been fighting for almost an hour. It was only 32 miles to Ða Năng. Where was the flare ship? Where was the air strike?

Smiley and I headed back to Disser’s position to see how things were going at the front gate. As we passed by the supply room, the ammunition blew apart with a tremendous explosion. For the third time, I was knocked down hard, and for the first time I felt real pain. My left leg hurt where it was torn by shrapnel. I pulled myself up and made it to Disser’s pit, the faithful Smiley right behind me.

It was a hellhole.

The V.C. had breached the outer perimeter and completely overrun Strike Force Company 122. They were at the inner perimeter barbed wire. Our mortar and automatic-weapons fire made them keep their heads down and move with caution. But they were within easy grenade-throwing distance. They bombarded us with grenades in volleys — five, six, seven at a time.

Jay heard a thud behind him and looked back. A fragmentation grenade rolled around by his feet. Inches away, it hit like a sledgehammer blow against the soles of his boots. He knew that the bones were broken. He carefully tightened his boot laces and tied them securely around his bare ankle, hoping to stop the bleeding and keep the bones together.

More grenades went off in the pit. Disser, crouched alongside his mortar, was wounded in the knees, the arms, and the legs. He kept on firing.

A grenade bounced into the bunker and landed in an ammunition box alongside Disser. Jay and Alamo dove to the right, Mike to the left. The blast tore into Mike’s foot and lower leg. He crawled back to his mortar and started firing it again.

Alamo slumped on the steps, bleeding from the shoulder and from a fresh hole just below the eye. Jay, sitting in the bunker doorway and passing ammunition to Disser, was a mass of wounds. He was hit in both legs, the left hand and elbow, the shoulders, and the back. The grenade barrages had jarred him loose from his weapons, and he looked about for something, anything. He resolved to leap upon the first V.C. to enter the pit and fight him with his bare hands.

Knocked down by an exploding grenade, trying to shake off the bewilderment, I fired into the darkness. Mike was trying to keep his mortar going, with two Nungs now helping him and Jay passing them ammunition.

“This is for Pop!” Jay yelled, passing Mike a round. Mike grabbed it, shouted, and launched it.

“This one’s for Conway!” Jay yelled, passing another round. They worked that way, yelling and firing, talking it up in a frenzied rhythm, performing in their own private hell. But the bedlam of bursting grenades was too much. In desperation we were picking up grenades and throwing them out of the pit before they could go off.

“Let’s get the hell out of here!” Mike yelled.

“Right!” I yelled back.

As if for emphasis, a concussion grenade exploded, knocking Mike and me down. Mike’s whole side was numb and he moved like a drunken man.

“Get out!” I cried.

Mike and Smiley evacuated the pit first. Jay and the Nungs followed them. Jay, as chopped up as he was, went out the same way he came in, loaded with weapons. I fired cover for their withdrawal to an 18-inch-deep ditch we had dug for burying communications wire.

Pop Alamo was sitting on the steps, bleeding from the face, the shoulder, and the stomach. I yelled to Mike and Jay to cover me, got one of Pop’s arms around my neck, and started to straighten up. I was in about a half-standing position when a tremendous blast went off in my face. It must have been a mortar hit at the top of the stairs. I could hear myself screaming as I flew through space. I had the sensation of falling backward off a cliff. I am going to die, I thought.

I came to with my head and shoulders inside the ammunition bunker, the rest of me outside. My left shoulder was all bloody, and intense pain shot from there down to my fingertips. My head, which had been aching since the first explosion, was bloody, too, and pulsed with pain. My stomach wound was bleeding. But I was alive.

Alamo was sprawled in the pit. He was dead.

I picked up the 60 mm mortar and moved out. Thirty yards away, I ducked behind a pile of cinder blocks. Four wounded Nungs were there. One of them had half his scalp torn away. I took off my jacket and my T-shirt and tore the T-shirt into bandages and patched up the men. I had a little piece left over, and I stuffed this into my stomach wound to try to stop the bleeding. I used one of my raggedy socks as a tourniquet on one of the men.

“Come on, you fellows are going to be all right,” I said to the Nungs. “You can still fight. Here’s your weapons. Cover me.”

I propped them up along the cinder blocks, their carbines in their hands. I shoved the mortar behind them and started to run back. But I couldn’t straighten up for the pain. I had to stay bent over, walking.

I went back to Woody’s pit, yelled out who I was so the Nungs wouldn’t shoot, and lay down on the rim, too exhausted to climb down inside. Woody’s feet were cut and bleeding.

I asked him how he was.

“Hell, I’m all right,” Woody said. “But I think my right eardrum’s busted. I felt some liquid running out of it. How’s everybody else?”

I hesitated. We used to argue in training about whether it was wiser to lie to your men when they were taking heavy casualties. There are two schools of thought. I decided that with these men, the bitter truth would make them fight harder. I was right.

“Alamo’s dead, Houston’s dead, Conway’s dead,” I told him. “Lieutenant ‘O’ and Disser are wounded. Brown’s wounded. Terry’s wounded. I don’t know about Beeson. I can’t get to him.”

Woody took the news without a word of comment. But I know now that he thought it was the death sentence for all of us. Isolated as he was, all he knew of his certain knowledge was that three men of our 12-man team were yet alive; he and I and Whitsell, out of contact but obviously firing furiously. Where were our planes?

A few minutes later, when I ran into Gregg, he insisted on checking me over. “You’re all shot up,” Gregg said. “Hold still and I’ll fix you up.”

“No,” I said. “There are a lot of them worse off than me. Take care of them and catch me later.”

I left for the main gate. I had an idea there would be a determined assault in that area. Perhaps I could get the Nungs to move the 60 mm mortar back into Disser’s pit. We would need it as a strong point. I saw no end to the pressure. We had been fighting for more than an hour and a half, without even a five-minute breather. Did anybody know?

And then I heard it. The distant hum of an airplane engine. It grew louder and louder.

The skies lit up. The flare ship had arrived. It was 4:04 a.m.

The plane brought a lot more than light. It brought hope to us in the camp, and it must have discouraged the V.C., for little by little their firing tapered off. A flare ship is usually followed by an air strike, and they knew it. Within minutes they began to withdraw. But they were far from through with us.

In the flare-lit gloom of the broken terrain in front of Brown’s mortar pit, a loudspeaker suddenly cut on. A man’s voice began speaking excited, high-pitched Vietnamese. It shocked both sides into silence.

Dan grabbed Tet, the interpreter, and demanded, “What’s he saying?”

“He say lay down weapons. V.C. going take camp and we all be killed.”

Dan, Gregg, and Brown exchanged hard looks of anger.

“Over my dead body,” Dan said.

“We’ll lay down our weapons when we’re too dead to pick ’em up,” Gregg said. But the silence held. Nobody in that sector was firing at all. The silence was unnerving. And then it was broken by the voice from the loudspeaker again, this time in English.

“We are going to annihilate your camp; you will all be killed!”

Brown was already adjusting the elevation on his mortar. “Where do you think it is?”

“Over here,” Dan said, pointing.

Brown fired about 10 rounds of high explosive and white phosphorus as fast as he could. The bursts broke the spell. The Nung machine gun on the right began chopping again. Small-arms fire resumed all around the pit. Incoming fire answered back.

There was another new sound; 60 mm mortar shells were walking toward the pit from within the camp.

“That mortar’s close,” Brown said.

They could hear the thunk of the shell sliding down the tube, the small explosion of its launching, and the roaring impact of its landing in back of them.

Off to the left, the loudspeaker came on again. Brown wheeled his mortar to the left and smothered the place where the sound was coming from with high explosive and white-phosphorus rounds. That was the last we heard of it.

Daylight was coming on by the time I finally got to Beeson. Gregg was in the pit, treating a wounded Nung, when I arrived. It was five, going on six, and the spaces between the V.C. mortar volleys seemed to be getting longer.

“Sit down, Captain,” Beeson said gently.

“Naw, I’m all right,” I said automatically.

“Sit down, sir,” Beeson said, still gently, “or I’m going to have to knock you down.”

He sat me on an ammunition box and started looking at my wounds. I felt the strength draining out of me.

Beeson put a bandage on my shoulder, but I wouldn’t let him work on the stomach wound. I had to go make the rounds again to brace for a possible new attack.

I walked out of Beeson’s pit without bothering to duck. After all those hours of twisting, crouching, and crawling, I was sick of it all. To hell with it, I thought. A hand grenade went off and knocked me down. I got up and walked to the makeshift C.P. that had developed behind the cinder blocks near Whit’s and Woody’s positions at the main gate.

About 50 yards in front of Woody’s, I saw four or five V.C. behind some tree stumps.

“Can you drop an 81 on them that close, Woody?” I called out.

“I never did it before, but I could damn well try,” Woody said.

Without using the sights, he put the tube almost straight up. The tree stumps blew sky high, and with them the last of the V.C. Except for sporadic small-arms fire, the battle for Nam Ðông was over.

A lot has happened since then. While I was in the hospital, Team A-726 was reactivated and saw more action — Brown, Beeson, Dan, Gregg, and Whit forming the nucleus — until last November when those five and I flew home together.

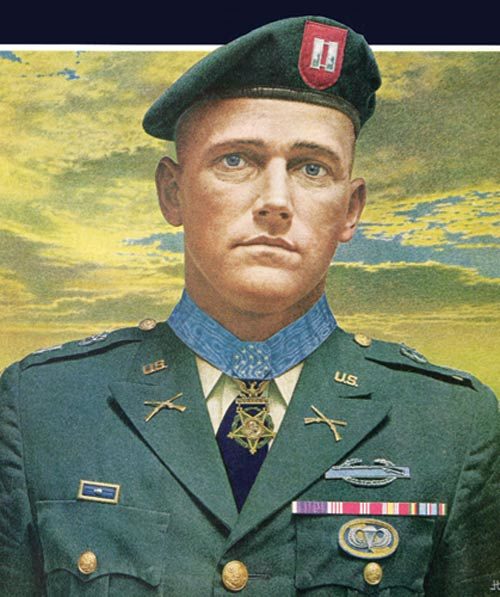

Pop Alamo and John Houston — God rest their souls — were posthumously awarded the nation’s second-highest military decoration, the Distinguished Service Cross. They were the only members missing when we assembled at the White House last December 5 as one of the most decorated units in Army history — Silver Stars to Olejniczak, Brown, Disser, and Terrin; and Bronze Stars with “V” for Valor to Beeson, Daniels, Gregg, Whitsell, and Woods; as well as nine Purple Hearts among us (all but Bee, Dan, and Gregg were wounded).

The Medal of Honor which President Johnson awarded me belongs equally to all of us. I solemnly pledge that whatever good flows from it for me will be passed on, intact, to the valiant men of my team, Detachment A-726 of the 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne).

—“The Battle for Nam Đông,” October 23, 1965

Excerpt from Outpost of Freedom by Capt. Roger H.C. Donlon, as told to Warren Rogers. ©1965 McGraw-Hill Education. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I live right down the street from Roger donlon,my uncle Vernon Beeson served with him ..

This is a great article and Colonel Donlon’s book is better yet. I’m a songwriter and Vietnam Veteran and friend of Colonel Donlon and am trying to figure out how to get permission to use the photo/artist rendition of Colonel/Captain Donlon used in this article, to use it on the cover of the album of a single I am going to release about Colonel Donlon’s Nam Dong, put to words and music. Can you help me get permission or the contact who can give permission to use the photo/artist rendition. I’m a retired Lieutenant Colonel, US Army, 2 tour Vietnam Veteran, song writer and music producer.