This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As part of her acceptance speech for the 2018 Golden Globes’ Cecil B. DeMille Award, Oprah Winfrey highlighted the life and legacy of Recy Taylor. Taylor, who passed away on December 28 at the age of 97, was 24 years old and a new mother when she was abducted and raped by six white men in her hometown of Abbeville, Alabama, on the night of September 3, 1944. Although her rapists threatened to kill her if she spoke out, Taylor reported the crime anyway, and the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP sent a young investigator named Rosa Parks to Abbeville. Parks and others would subsequently start “The Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor,” working to draw national media and public attention to this brutal crime that was tragically representative of many African American women’s experiences.

Taylor’s story and life are well worth remembering for their own sake, but it was Taylor’s link to Rosa Parks that led to the Montgomery bus boycott and the early Civil Rights Movement. Long before hashtags and social media, Taylor and Parks were the creators of the original #MeToo movement.

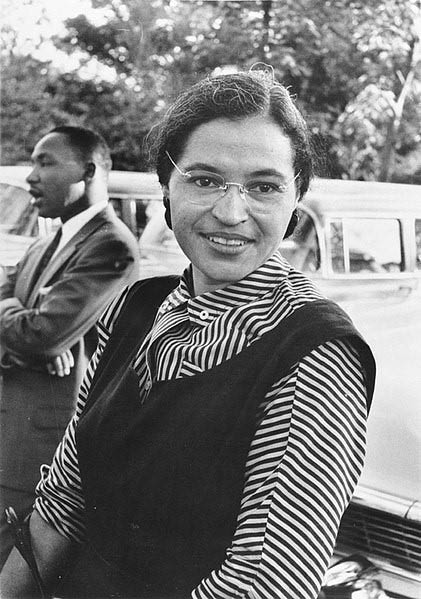

Rosa Parks’ refusal to move to the back of the bus was not only the origin of a movement, but also, as historian Danielle McGuire has traced at length, a culmination of the campaign against sexual and racial violence that began in earnest with Taylor and continued to grow from there.

After helping Taylor, Parks began to fight back against systemic sexual and racial violence against African American women in Montgomery. On March 27, 1949, Gertrude Perkins was arrested for “public drunkenness” by two white police officers, who then raped her at gunpoint. When Montgomery mayor W.A. Gayle refused to take any action, arguing that “my policeman would not do a thing like that,” Parks and others formed a “Citizens Committee for Gertrude Perkins.” Although Perkins’ case did not get beyond a grand jury hearing, the Citizens Committee led lengthy protests that forced the two police officers out of the city.

Mayor Gayle was of course tragically mistaken about what white policeman would and did do to African American women. But there was another group who represented at least as much of a threat: the city’s bus drivers. They were granted the equivalent of police power in order to enforce segregation laws, and were allowed to carry blackjacks and guns. They used that power and those weapons far too often for awful purposes: Between 1953 and 1955, African American women filed more than thirty abuse complaints against white drivers with the Montgomery City Lines company, for charges ranging from sexual insults and inappropriate touching to abuse and rape.

Those complaints came to the attention of the African American Women’s Political Council, who began advocating for a boycott. Rosa Parks was actually the third activist arrested in 1955 as part of those efforts, following 15-year-old Claudette Colvin and 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith.

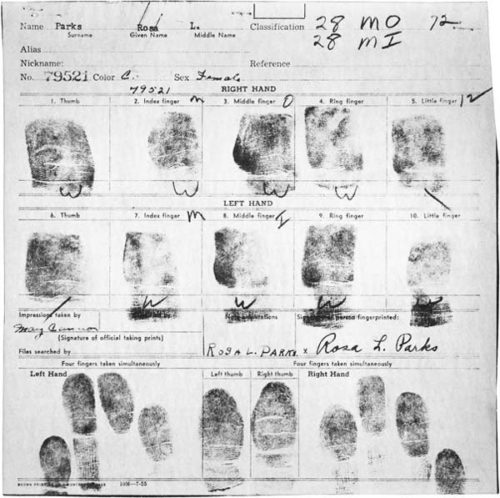

But it was Parks’ December 1 arrest that finally broke the dam and launched the boycott in earnest. Immediately after Parks’ arrest, WPC leader JoAnn Gibson Robinson called for a boycott of city buses on Monday, December 5. She asked “every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial,” distributing more than 50,000 flyers throughout the city.

The boycott would last for eleven challenging and crucial months. On that same day, Robinson and other women leaders founded the Montgomery Improvement Association to coordinate the boycott, publishing a newsletter, organizing volunteer transportation, and keeping the process running as smoothly and successfully as possible. Soon many other activists and organizations would join and amplify the cause, with a young minister named Martin Luther King Jr. (then preaching at Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church) prominent among them.

But it was Montgomery’s women—Robinson and the WPC, Parks and NAACP, and most especially citizens like Gertrude Perkins, Claudette Colvin, and Mary Louise Smith—who truly launched the boycott.

They did so as civil rights leaders, as social and political activists, and as community organizers. But they also did so in solidarity with one another, and with the countless African American women who were mistreated, abused, and violated. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Civil Rights Movement began with a potent #MeToo moment, an outraged expression of and impassioned resistance to shared experiences that cut across lines of gender and race, sexual and racial violence.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now