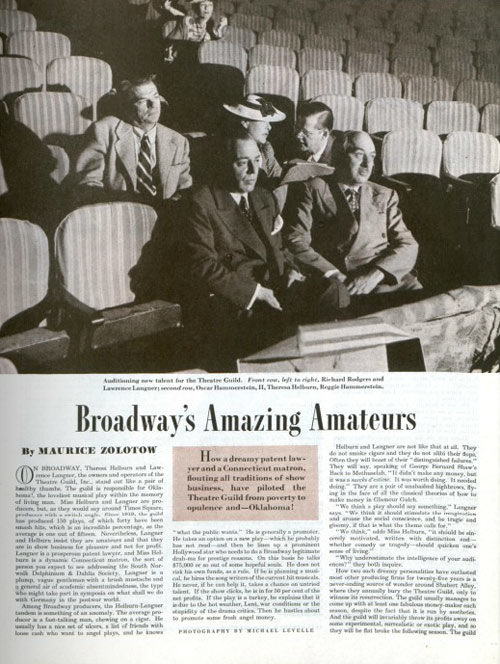

The Legacy of Oklahoma!, the First Broadway Musical Sensation

Theresa Helburn, of the prestigious Theatre Guild group, was seeking just $35,000 more to stage a musical version of Lynn Riggs’s Green Grow the Lilacs in 1942, but it was difficult to convince investors to fund the project. More than 50 people turned her down, possibly because of the group’s failed production of the straight play in 1931. Helburn and her partner Lawrence Langner drummed up the necessary support, however, and opened the musical Away We Go for previews in New Haven, Connecticut.

After some changes to Away We Go — songs were shuffled and unruly onstage pigeons were nixed — the musical in its final form, Oklahoma!, opened 75 years ago on Broadway. The naysayers of the New York theater crowd didn’t just underestimate the show’s potential; they passed up the opportunity to take part in the first Broadway musical smash hit.

Public interest in the show grew exponentially after its Broadway premiere, leading one radio announcer to quip, “Look at that play Oklahoma! A man died last week and left his place in line to his wife. If she dies before she gets her tickets, her place in line goes to an uncle in Baltimore.” Reportedly, the $4.80 tickets were going for as much as $50 on the street.

The folksy musical was the first collaboration between composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II. It was also among the first ever musicals, as we typically know them today. Oklahoma! told an ambitious story coherently using lyrics, dance, dialogue, and music — a form considered a “book musical.”

Rodgers and Hammerstein would go on to rule Broadway in the postwar years with their saccharine portrayals of romance and morality like South Pacific, The King and I, and The Sound of Music. Stephen Holden wrote of the duo, in The New York Times: “The America of Rodgers and Hammerstein — where the good guys won, love conquered all and progress was taken for granted — was itself a dream, a golden bubble of postwar hope and confidence that evaporated more than it burst.” Before it dissipated, however, the Rodgers and Hammerstein machine altered musical theater, and perhaps all music, for good.

A Salute to Baseball in Film

For opening day, our resident movie buff Bill Newcott assembled his favorite scenes about our national pastime.

News of the Week: Baseball Starts, Groucho Sings, and You Might Get $100 in the Mail

Buy Me Some Peanuts and Cracker Jack

It’s funny how you can love some things deeply and then drift away from them over time. I’m not talking about people — though that can happen too. I’m talking about things you enjoy, your hobbies, and the ways you spend your time.

That happened to me and baseball. It’s the only sport I played as a kid (left fielder and pitcher), and I grew up obsessed with the Boston Red Sox. At one time I could not only tell you the team’s lineup, but also their batting averages. I loved baseball throughout my teens and early adult years, too.

Then in my late 20s, I became obsessed with tennis, and my knowledge of how many home runs Carl Yastrzemski hit was replaced with how many Grand Slams Roger Federer has won. I was emotional about the Red Sox World Series win in 2004 — after an eight-decade drought — but their 2007 and 2013 championships I watched only as a fair-weather fan, not as someone with a solid interest. Just yesterday, I saw the lineup for this year’s team, and I can only name three or four players, and the only reason I can is that they’re the ones who have been on the team the longest. Sorry, Blake Swihart and Craig Kimbrel!

Baseball season started yesterday, and if you’re still a fan and plan on watching a lot of games this summer, here’s ESPN’s schedule for the entire season, for every team. Maybe I’ll try to catch a Sox game on one of these warm nights, when there isn’t a tennis tournament being played somewhere in the world.

Since I mentioned “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” here’s how Cracker Jack got its name.

When Her Muscles Start Relaxin’, Up the Hill Comes Andrew Jackson

Quick question: What do Groucho Marx, Tony Bennett, and Harry Belafonte have in common? They’ve all made recordings that were just inducted into the National Recording Registry.

Bennett’s “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” entered the ranks, and so did Harry Belafonte’s album Calypso. Twenty-three others got the honor too, including “Footloose” by Kenny Loggins, “My Girl” by the Temptations, Run-DMC’s album Raising Hell, Artur Schnabel’s The Complete Beethoven Sonatas, and the soundtrack to The Sound of Music.

I know what you’re thinking: Groucho Marx? All recordings that are “recognized as vital to our nation’s audio legacy” are celebrated, and Groucho is in for his 1972 album An Evening with Groucho, which includes the song “Lydia, the Tattooed Lady,” originally sung in the movie At the Circus.

USS Juneau Found

The story of the five Sullivan Brothers, who all died aboard the USS Juneau during World War II, is one of the saddest stories of any war. It not only led to new rules regarding how many family members can serve in the military at one time, it was the inspiration for the movies The Fighting Sullivans and Saving Private Ryan. Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen and his research company recently found the wreck of the ship at the bottom of the South Pacific, 76 years after it sank.

Drink, Click, Buy

I’ve never bought anything after having a few too many cocktails. Oh, I can remember years ago buying a lot of fast food after a night of drinking, but I’ve never had too much to drink and then gone online and bought something I didn’t need. But apparently that’s a real problem, with people spending an average of $448 last year on tipsy purchases.

I have a problem with this news being described as “costing America $30 billion.” If you’re spending money online, isn’t that good for the companies you’re buying from? And if it’s something you want or need, whether it’s a book, a new jacket, or a subscription to your favorite magazine, how is that a bad thing?

National Poetry Month

The April celebration doesn’t start for two more days, but you can get a jumpstart by reading this piece in The Paris Review on Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” which they call “the most misread poem in America.”

I never knew it was once used in an ad for Mentos.

RIP Louise Latham, Linda Brown, Zell Miller, Frank Avruch, and Charles P. Lazarus

Louise Latham was best known for her roles in movies like Marnie and Firecreek, as well as TV shows such as The Fugitive, Perry Mason, Columbo, The X-Files, ER, and Murder, She Wrote. She died in February at the age of 95.

Linda Brown was not allowed to attend an all-white school, which led to the famous Brown v. Board of Education court case that ended school segregation. She died Sunday at the age of 75.

Zell Miller was a Democratic governor of Georgia from 1991 to 1996 and a senator from 2000 to 2005. He also once challenged MSNBC’s Chris Matthews to a duel! He died last Friday at the age of 86.

Frank Avruch was a longtime host of Boston TV shows, including The Great Entertainment and Man About Town. He was also one of the guys who played Bozo the Clown, wearing the makeup throughout the 1960s. He died last week at the age of 89.

Just a week after it was announced that Toys ’R’ Us is going out of business, the founder of the chain, Charles P. Lazarus, has died. He was 94.

Quote of the Week

“What’s up, deplorable?”

—liberal Jackie to her conservative sister Roseanne on ABC’s Roseanne reboot, which returned to massive ratings

The Best and the Worst

Best: Can you imagine someone starting a job today and staying at that same job for 50 years? Sue Scheible went to work for The Patriot Ledger in 1968, and she’s still there. She wrote a great top-ten list of her reasons why she’s still on the job.

Worst: Valpak, the coupon company with the blue envelopes, is also marking 50 years. In celebration, they’re randomly sending people checks in those envelopes. I didn’t pick this as a “worst” because this is a bad idea — good for them! — I picked it because I didn’t get one.

This Week in History

Vincent van Gogh Born (March 30, 1853)

Vincent van Gogh: painter of famous masterpieces, slicer of ears, and subject of a popular sad song from the ’70s.

Jeopardy! Debuts (March 30, 1964)

The original star was Art Fleming, who hosted the show until 1975 and then again in a revamped version in 1978-79. Alex Trebek has hosted the current syndicated version since 1984.

I couldn’t find video from the first season, but here’s an episode from 1974:

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Greyhounds (March 29, 1941)

Paul Bransom

March 29, 1941

I could tell you that I picked this Paul Bransom cover because I like the use of neutral colors and that it’s a different type of cover for the Post, but the truth is, I just really love dogs.

Easter Recipes

We don’t celebrate Easter in my family. It’s one of those in-between holidays, more important than Groundhog Day, but not as important as Thanksgiving, so it’s just another day for us. No ham, no colored eggs, no chocolate. Well, actually, there will be chocolate on Easter. There’s always chocolate! It just won’t be shaped like a bunny.

But if you plan on making a meal for your family on Sunday, you can try Curtis Stone’s Roasted Pork Loin, these Maple Dill Carrots, and this Easter Bunny Cake, which is equal parts adorable and horrifying.

And if you plan on having a lot of people over for dinner, try one of these four farm recipes for home-cured ham from 1950.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Men’s Final Four (March 31-April 2)

I’m not sure how you did in your bracket (do I have the terminology right? I watch basketball even less than baseball), but the final four going for the NCAA Men’s Championship are Kansas, Villanova, Michigan, and Loyola Chicago. Here’s the CBS and TBS broadcast schedule.

April Fools’ Day (April 1)

You could spend the day playing cruel jokes on your friends and family, or you could try to spot all 45 errors in this classic Norman Rockwell Post cover from 1943.

Jesus Christ Superstar Live (April 1)

This live musical, airing at 8 p.m. on NBC and starring John Legend, Sara Bareilles, and Alice Cooper, is the latest live event from the network, after The Sound of Music, Peter Pan, The Wiz, and Hairspray. They’re producing A Few Good Men later this year.

Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One

Movie critic Bill Newcott reviews Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One, The Death of Stalin (including some vintage words of wisdom from Mel Brooks), and the documentary More Art Upstairs. Also don’t miss Bill’s home video quick hits, including his reviews of All the Money in the World, Molly’s Game, The Commuter, The Post, and The King of Jazz.

Unfinished Business

The legend, at least, was that the view up there was beautiful.

In the nearly two decades that Steve Reeb had worked in the building he had never gone up to the 13th floor. His department was located on 12, and he never had a reason beyond itching curiosity to venture up the flight.

But how many times had his finger strayed over the forbidden elevator button?

Now, idling in his car in the parking lot in the fading winter light, he no longer itched. He fairly burned.

He glanced at his watch. It was 4:30 p.m.

Lynn had urged him that morning to drive away and never look back. He knew his wife was right — better to leave head held high.

“Don’t take it personal,” she had begged him, pressing his gray head against her own. “It’s just the times. You lasted longer than anyone.”

What was she afraid of? In the rearview mirror he glanced at his face — lined and imperfectly shaven.

Haunted, perhaps. But disgruntled? He loathed the word.

His gray eyes roved back to the building. A spider fern and a box of possessions — mostly paperclips and hobby photographs of birds — slumped in the passenger seat.

A gust of wind rolled off the river and struck the car door like a bowling ball. Still, he stared.

I lasted longer than anyone. A realization crept into Steve Reeb’s mind. I’m the only one who remembers what happened.

A sudden buzz in his pocket almost made him cry out. He fumbled for the phone.

It was a text from Lynn: “See you soon. Did they give you a ‘retirement’ present?”

He pocketed the phone without answering. He reached for the ignition. Turned it off.

Steve Reeb had made up his mind.

Feeling beneath his seat, he ripped something from its case unceremoniously and tucked it under his coat.

The car door slammed and he directed his feet towards the lobby.

Inside, he headed straight for the bank of elevators. He moved swiftly and tried not to look at anyone. The faces he met were all unfamiliar — ordinary souls from the other floors whose names he never learned and departments he could only guess.

He was relieved to find himself alone in the empty silver elevator car. If he encountered one of his own coworkers — someone he cared about like Darryl, Mike, or Janet — he knew he would lose his nerve.

But alone, absent questions or prying eyes, he depressed the 13th button. Part of him doubted whether it even functioned any more. But the numbers glowed to life, and he felt the car lurch upwards.

The floors dropped away like pings of rain.

One. Two. Three. Four …

Steve Reeb rose in body. But in spirit he sank backwards in time.

How long ago was it? He reflected darkly. Almost 18 1/2 years.

Five. Six. Seven. Eight …

He had been on the job just a matter of months when it happened. If memory served, he had just come back to his desk from getting a fresh cup of coffee, was just settling down in his chair when he heard the first screams through the ceiling.

Nine. Ten. Eleven.

I just sat there, he confessed to the empty elevator car.

Twelve.

I just sat there.

Thirteen.

The silver doors parted.

One small step for a man. His heart beat painfully. One giant leap for Steve Reeb.

Instead of the moon, he found himself standing on a thickly dusty office carpet in a spare and abandoned cubicle farm.

Most of the furniture had been removed. What was left — chairs and a few desks with unplugged phones — were covered in white sheeting. Even beneath their shrouds, they looked outdated. The plastic had all yellowed.

Of course, the whole floor has been shuttered after the incident. They picked up and moved the entire department to another building. Some of the survivors never came back to claim their belongings.

Tragedy never sleeps. It hung in the air around Steve Reeb like invisible smoke.

People died here.

And if the news reports were right, behind one of these desks the shooter had turned the gun on himself.

He moved slowly towards the large bank of windows where the late afternoon light poured and pooled on the carpet beneath.

He tried not to fixate on the ugly, round putty-filled holes that pocketed the walls. Instead he looked beyond, to the river stretched out like a cool white opal. The ghostly specks were tundra swan.

For a few minutes he watched them dance through new binoculars.

He tucked his “retirement” gift back under his coat and turned to leave. He had seen enough to know the legend was true, and he would drive away without glancing back.

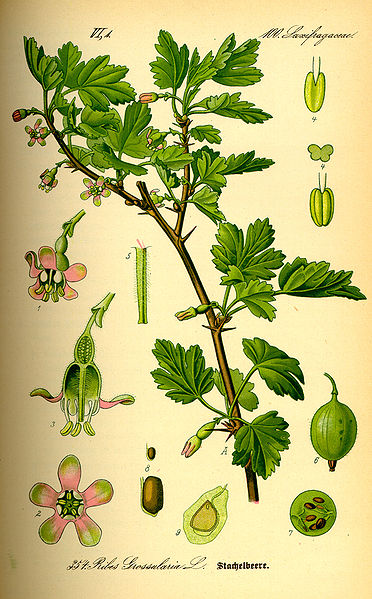

Try These 150-Year-Old Gooseberry Recipes

Try these delicious and unusual recipes for the gooseberry, aka “sour grape.”

Gooseberry Fool

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, May 30, 1868

Gooseberry fool made by the following recipe is much liked by my own family, and has always been highly approved of by any friends who have tasted it:—Wash a quart of full-sized green gooseberries, put them into an enameled saucepan, cover it tightly, and set it on a trivet some distance from a slow fire. Shake the saucepan frequently that the gooseberries may not burn. When perfectly tender, turn them out on a coarse sieve, and rub them through it; and moist sugar to taste, and a little nutmeg. When quite cold mix with them a pint of milk and two eggs very thoroughly beaten, which answer the purpose of cream. Serve either in a glass dish or in custard cups.

Gooseberry Jam

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, July 12, 1856

Pick and clean red gooseberries, thoroughly ripe. Boil them by themselves for 20 minutes, skimming them frequently. Then add brown sugar, in the proportion of one pound of sugar to one pound of fruit. Boil for half an hour after the sugar is in. Skim it, and pour it into earthenware jars. When cold, paper up the jars, and set aside in a dry cool situation. Strawberry, and black currant jams are made in precisely the same manner as the above; but instead of brown, use lump sugar.

Green Gooseberry Cheese

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, June 2, 1866

Take six pounds of green gooseberries before they begin to ripen; snip them carefully, taking off both ends quite clear; then put the gooseberries into cold spring water, and let them remain for two hours. Then take them out and bruise them in a wooden vessel; put them into a preserving-pan and stir them over a clear fire till they are quite tender. When reduced to a pulp add four pounds and a half of powdered loaf sugar, and boil till the mixture becomes quite thick and is of a good green color. Stir it frequently; pour into moulds.

Gooseberry Champagne

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, September 8, 1866

Take large, fine gooseberries, that are full-grown, but not yet beginning to turn red; and pick off their tops and tails. Then weigh the fruit, and allow a gallon of clear, soft water to every 3 pounds of gooseberries. Put them into a large, clean tub; pour on a little of the water; pound and mash them thoroughly with a wooden beetle; add the remainder of the water, and give the whole a hard stirring. Cover the tub with a cloth, and let it stand four days; stirring it frequently and thoroughly, to the bottom. Thin strain the liquid, through a coarse linen cloth, into another vessel; and to each gallon of liquid add four pounds of fine loaf sugar; and to every five gallons a quart of the best and clearest French brandy. Mix the whole well together; and put it into a clean cask, that will just hold it, as it should be filled full. Place the cask on its side, in a cool, dry part of the cellar; and lay the bung loosely on the top. Secure the cask firmly in its place, so that it cannot, by any chance, be shaken or moved; as the least disturbance will injure the wine. Let it work for a fortnight, or more; till the fermentation is quite over, and the hissing has ceased. Then bottle it; driving in the corks tightly. Lay the bottles on their sides. In six months it will be fit for drinking, and will be found as brisk as real champagne.

Gooseberry Wine

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, June 8, 1867

Take 40 pounds of nice large gooseberries before they commence to turn ripe, but not before fully grown; remove the blossoms and tails; bruise the fruit without crushing the seeds or skins; add to the pulp four gallons of soft water, stir and mash the fruit in the water until the whole pulp is cleared from the skin ; let it stand for six hours, strain it through a coarse bag or sieve that will not let through the seeds; bring the water and juice to boiling heat, and dissolve 30 pounds of white sugar, and add it to the liquor ; pass a gallon of water through the mass, strain, and add it to the mixture; measure the wine, and add soft water until it measures 10 gallons. Let it ferment as currant wine. Leave the barrel tightly bunged after the fermentation has ceased, until it is drawn off to bottle.

Green Gooseberry Pudding

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, May 21, 1870

Line a tart-dish with light puff-paste; boil for a quarter of an hour one quart of goose- berries with eight ounces of sugar and a teacupful of water. Beat the fruit up with three ounces of fresh butter, the yelks of three well-beaten eggs, and the grated crumb of a stale roll. These should be added when the fruit is cool. Pour the mixture into the dish, and bake the pudding from half to three-quarters of an hour.

Some Gooseberry Goodies

Originally published in The Country Gentleman, June 27, 1914

The small, sour, green gooseberry of the old-time garden was neglected with good reason. Numerous thorns made the fruit hard to pick, and the berries made too tedious work to bother with in the rush of preserving season. But now that improved culture has given us big, juicy, fine-flavored berries, which may be quickly prepared for summer desserts and for winter use, the old prejudices are passing and the berry is coming into its rights.

Two Takes on Gooseberry Pudding

A steamed gooseberry pudding, in a deep pudding dish, with plenty of fruit and flaky pastry, is a novelty that is certain to become a favorite dessert. Prepare a rich biscuit dough, roll out to half an inch in thickness, line a pudding dish with it, and fill with large, ripe, tender gooseberries. Sweeten well, with a good proportion of brown sugar or a tablespoonful of molasses added to granulated sugar to give the desired flavor. Cover with a top crust, tie a floured cloth securely over the top of the pudding dish, set it in a covered pan of boiling water, and steam for two hours.

For another form of steamed pudding the gooseberries are mixed directly with the batter. Two tablespoonfuls of butter are creamed with one cupful of sugar, a cupful of sour milk is added, with half a teaspoonful of soda dissolved in a little cold water, and sufficient flour to make a rather stiff batter. Stir in a heaping cupful of gooseberries. At the last beat in the whites of the eggs, turn the batter into a buttered pudding dish, cover closely, and steam two hours.

These puddings may be served with creamy vanilla or lemon sauce. But for variety and novelty try a rich gooseberry sauce, made by cooking the berries in very little water until tender and passing them through a fine sieve. To half a cupful of the smooth pulp add the same amount of sugar and water and boil for a few minutes; thicken slightly with a teaspoonful of cornstarch wet with cold water. When cold beat the white of an egg quite stiff, and with an egg beater combine the thick sauce with the egg.

Multitasking a Bavarian Cream

Gooseberry Bavarian cream is a convenient dessert that may be prepared while cooking breakfast, to be served cold for dinner. Rub a bowlful of hot, stewed berries through a sieve, and to one cupful of the pulp add half a cupful of granulated sugar. Soak a tablespoonful of gelatin in water until dissolved, stir it into a cupful of boiling water, then add the sweetened gooseberry pulp. When it begins to cool beat briskly until it thickens, adding a cupful of rich milk; beat again until thick. Turn into a mold; serve with whipped cream.

Making Roly-Poly

Gooseberry roly-poly may be either steamed or baked for a rich and novel dessert. Sift together one and a half cupfuls of flour, a teaspoonful of baking powder, and half a teaspoonful of salt. Rub in two tablespoonfuls of butter — or one of butter and one of lard — and mix with sufficient sweet milk to make a soft dough. Work lightly with the fingertips, turn the dough on a floured board, and roll into a sheet about half an inch thick. Spread thickly with rich gooseberry pulp that has been rubbed through a sieve and sweetened. Roll up like a jelly roll. Pinch the ends carefully together to keep in the pulp and juice, and tie a thin layer of cheesecloth about the long roll to keep it in shape. Steam for an hour, then remove the cloth, place the roll on a buttered pie plate, and brown for a few minutes in the hot oven. Cut thick slices across the roll and serve hot with whipped cream or a favorite pudding sauce.

One- or Two-Crust Pies

Most gooseberry recipes are improved if the berries are boiled until the skins crack open and then rubbed through a sieve for a smooth pulp. An exception may be made for the two-crust gooseberry pie, which is improved when made with the whole berries if they are of the big, tender, thin-skinned variety. Have the crusts of rich, flaky pastry. Fill the pie plate rather full of berries, as they will shrivel in cooking; add a generous quantity of sugar if the berries are tart, and sift sufficient flour over them to absorb the surplus juice in cooking. Bake quickly in a hot oven until the berries are thoroughly done and the pie well browned. Sift powdered sugar over the top when cold.

For the one-crust gooseberry pie use the rich pulp rubbed through a sieve, with all skins removed. The pulp should be well sweetened while hot and beaten with half a teaspoonful of butter and two tablespoonfuls of cream for each pie. Spread thickly on the under crust, bake in a hot oven, and finish with a meringue, as for lemon pie. Or, if preferred, give a generous coating of whipped cream and powdered sugar when the pie is cold.

An Unusual Salad

Chinese salad is a spicy novelty when served with gooseberries. Wash and boil a cupful of rice. When thoroughly done dash cold water over the rice and drain. Select a pint of gooseberries; chop them lightly, leaving them in rather coarse pieces; sprinkle enough sugar over them to enrich the acid flavor without making them sweet. Make a rich dressing of six tablespoonfuls of olive oil, three tablespoonfuls of lemon juice, and one tablespoonful of soy. Beat the oil and lemon juice until quite thick, add the soy, and beat again until well blended. When ready to serve place the flaky rice on lettuce leaves, over the rice toss the chopped berries, and over the whole place the soy dressing.

Gooseberry and Ginger

For a delicious compote of gooseberries a combination of ripe gooseberries and candied ginger is a favorite relish. Bring a quart of gooseberries to a gentle boil, with a heaping cupful of sugar and a teaspoonful of ginger root minced very fine, or a quarter pound of candied ginger cut in long, thin strips. After simmering until thoroughly tender, remove the berries and ginger to the dish in which they are to be served, keeping the berries as whole as possible. Return the juice to the saucepan; boil a few minutes longer, until well cooked down; then pour it over the berries and serve when cold.

Uncooked berries are best for unsweetened shortcakes made of pastry dough; stewed gooseberry pulp is best for sweet cake. Gooseberry preserves may be cooked down to a rich, heavy sirup, with equal quantities of sugar and fruit, and the skins left in the preserve if the berries are of the thin-skinned variety. If the skins seem tough pass the berries through a sieve after they have been cooked slightly, and use the pulp both for thin preserves and for heavier jam, well cooked down.

Whole gooseberries and chopped ginger root, cooked in a spicy sirup with vinegar and sugar, form a winter relish that is very acceptable with cold meats. Other spices may be used if desired, a little mace and cinnamon blending well with the tart berries in the vinegar and sugar sirup.

Sponge or Float

Gooseberry sponge and gooseberry float are easily prepared desserts to serve after a substantial dinner, while more hearty desserts are dumplings and rich puddings. For the gooseberry float the cooked and mashed berries will be required. Have the pulp quite sweet, and for two cupfuls whip the whites of three eggs, with half a cupful of powdered sugar, until frothy and stiff. Then beat the gooseberries into the frosting, heap the mixture lightly in dessert glasses and serve very cold. Gooseberry sponge is made with gelatin. Half a box of gelatin is soaked in half a cupful of cold water, and then dissolved in hot sirup made by bringing to a boil one cupful each of water and sugar. When cool a cupful of gooseberry pulp is added to the gelatin, with the white of an egg, and the whole is thoroughly beaten until light and spongy.

Better than Apple Butter

A nutritious relish for the children is a spicy gooseberry butter. The gooseberries are simply hulled and boiled in a little sugar-and-water sirup with the favorite spices. The result is richer than the usual apple butter. To two cupfuls of gooseberries allow one cupful of water, one of sugar, and half a cupful of vinegar. Ground cinnamon and mace, a teaspoonful of each with half a teaspoonful of cloves, if the flavor is liked, should be stirred directly into the boiling sirup. Boil until the berries are done and the sirup begins to thicken. Then press through a sieve to remove only the coarsest skins and retain all the pulp possible in a thick mixture. Return to the fire for a few minutes and beat thoroughly while hot, with an extra cupful of sugar, to a heavy butter. The vinegar and spice will keep the butter from souring, and it may be made up in quantity.

Other Ideas

For pop-overs and tarts, for filling patties and gelatin cups, and for timbales and soufflés, the rich, spongy gooseberry pulp, served plain or whipped with cream or white of egg and sugar, may be made to serve a delicious change in company desserts. Plain tapioca pudding is greatly improved by stewing gooseberries with the tapioca. In the different forms of dumplings gooseberries may be cooked whole like cherries.

Post Travels: Below the Surface of the Beautiful Galápagos

A typical day in the Galápagos islands is anything but typical. As Saturday Evening Post editorial director Steven Slon wrote in The Bleak and Beautiful Galápagos, “the islands actually are extraordinarily beautiful — a beauty that stems in part from being unspoiled by man.”

From dancing blue-footed boobies to scuttling Sally Lightfoot crabs, at every turn, Mother Nature seems to be staging a flawless performance. But the best way to get close to the stars of the show, the Galápagos A-listers if you will, is to get below the surface.

Sailing with Metropolitan Touring, I spent a large amount of my time in the islands snorkeling with animals that have no fear of humans. Every time I put on a snorkel and mask, I was more dazzled by the marine wildlife that swam along and said hello. As highlights from my time underwater show, it always more fun swimming with a buddy.

Law Matters: Be Careful What You Post Online

Lew Tesser gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Timothy Nolen, Esq., associate at Tesser, Ryan & Rochman, Esq., in the preparation of this article.

Time after time, friends, family, employers and now even the courts remind us: be careful what you post online, as it may not be as private as you think. Whether you mark something as “private” or not, it might be used against you in court someday.

In recent years, technological advances have changed the way we live and work, but few developments have had as far-reaching an impact on our lives as social media. With friends and family posting more details than ever about their lives, it can be tempting to “put yourself out there,” in effect documenting daily activities on social media through postings and photos. For some of us who aren’t so open, it might be comforting to assume that carefully managing social media settings really will keep your information private, and that there is no downside as long as we don’t make our profiles public.

Think again! A recent case, which went all the way to the New York Court of Appeals (New York State’s highest court), made it abundantly clear that simply making your social media accounts private is insufficient.

In a case involving a woman who was severely injured when she fell off a horse, the woman sued the man who owned the horse for money damages. She claimed she had previously lived a very active life (which she had frequently posted about on Facebook), but now could not be as active due to both her physical and cognitive injuries. In a process called “discovery,” the owner sought access to the woman’s private Facebook postings and photos in order to see just how severely the accident had really impacted her day-to-day life. (“Discovery” is a procedure that requires individuals involved in a lawsuit to hand over certain documents or information.) The woman refused to hand over her private Facebook information, claiming among other things that it would be an invasion of her privacy.

In a decision that should give pause to many active social media users, New York’s highest court ordered her to hand over her private Facebook information. The court noted that “some materials on a Facebook account may fairly be characterized as private. But even private materials may be subject to discovery if they are relevant.” In other words, courts focus more on whether information is important or “relevant” to a case, and less on whether information is classified as “private” or “public.”

This is not to say that all users’ private social media must always be turned over in discovery. In order to gain access to such private social media information, the party seeking it must demonstrate that the social media content is likely to lead to relevant information.

So how could private Facebook information be relevant to determining whether the woman was injured when she fell of the horse? (She certainly wasn’t posting about it as it was happening.) As the court noted, reviewing her Facebook posts and photos might help determine just how “active” a lifestyle she really enjoyed before the accident. Or perhaps her recent private posts would demonstrate that, contrary to what she says, she still lives a very active lifestyle. Or maybe the fact that, post-accident, she was still able to write lengthy, complex and detailed Facebook posts would undermine her claim that she had suffered severe cognitive injuries and had “difficulty writing and using the computer.”

Court records do not reveal whether the search of her private documents revealed anything harmful to her, but the point is, it could have.

As the court’s reasoning demonstrates, you should be mindful that what you post on Facebook or any other social media site might be relevant at trial in ways that you would not normally expect. For example, perhaps your “checking in” on Facebook someplace five minutes before an accident could be used to prove you were near the accident when it happened; or maybe your use of nicknames on Twitter could help identify you in a situation where you were relying on anonymity; or maybe your Instagram post with language complaining about how you got a black eye might prove the real source of your injuries; or maybe your LinkedIn profile and postings might undermine your claim that you were disabled and couldn’t work.

Social media has been a terrific tool to bring friends, families, and even businesses together. But remember that just because you mark something as “private” doesn’t mean it can’t be used against you in court—another reason you should be careful what you post online!

(The Court of Appeals case discussed is Forman v. Henkin, 2018 N.Y. LEXIS 180 (Feb. 13, 2018). The examples of the relevancy of “private” social media postings are based loosely on recent New York cases.)

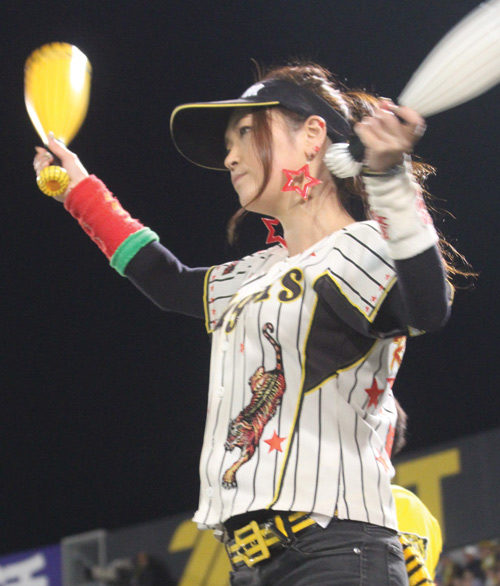

The Healing Power of Baseball in Japan

Cozy spring breeze

Over the grassy ground

How I want to play ball!

—Shiki Masaoka (1897)

Day 1: Tokyo

At the start of the Japanese baseball season this past spring, the breeze over the grassy ground at Tokyo’s historic Meiji Jingu stadium was not cozy. It was a brisk, moist wind that swept over the diamond and crashed into the stands. Fans rubbed their arms with gloved hands. Even so, it was time to play ball, and nothing was going to dampen their spirits. It was the opening series between the Tokyo rivals, the host Yakult Swallows and the visiting Yomiuri Giants.

In Japan, baseball is the national sport, but even that description doesn’t quite capture the intensity, emotion, and enjoyment the Japanese attach to its rituals. I travel not to see sights but to see what the people who live where I go really care about, and that’s what I was looking for when I set out on a short journey across Japan. In Tokyo, I had met up with Katsura Yamamoto and Nao Nomura, friends of friends from home, who were helping get me started.

Built in 1926, Meiji Jingu is a cherished venue like Wrigley Field or Fenway Park. The Swallows’ faithful wore the team’s alternative home jersey, a Day-Glo lime green that made the stands appear as if they’d been streaked with highlighter. Fan club captains, looking like martial artists in happi coats and black headscarves, shouted cheers through bullhorns. Fans serenaded players, such as the Swallows’ superstar second baseman, Tetsuto Yamada: Ya-ma-da! Ya-ma-da, Yamada Tetsuto! Ya-ma-da, Yamada Tetsutooooo! Yamada and the Swallows jumped on the Giants’ pitching early, and the fans stomped, high-fived, banged plastic bats, blew horns, and opened and closed plastic mini-umbrellas as players crossed home plate, a Swallows custom that made all of Meiji Jingu twinkle — except in left field, where Giants fans, wearing their team’s bright orange, sat, still and subdued, at least until the Giants came up to bat, when they raised such a ruckus that you might have thought their team was winning.

I hailed a “beer girl,” as the almost exclusively female purveyors of fresh brew in the stands are known. They run the stadium steps with kegs of Asahi, Sapporo, and Kirin in backpacks for more than three hours, but even more impressive are their indefatigable smiles.

“The pretty ones make more money,” Nao said. “Some of them have been discovered and became models or actresses. If they work for the Giants, they’re on television all the time.”

The Giants are Japan’s oldest and most beloved team. They’ve won 30 Japan League championships since the circuit was created in 1936. The Giants are also Japan’s most despised team, and my friends Nao and Katsura, historians in non-baseball life, love to hate them. Nao’s team is the Hiroshima Toyo Carp — her late father was from Hiroshima — while Katsura adores the Hanshin Tigers, the Giants’ archrivals, who play near Osaka. During the game, she frequently checked her phone for Tigers updates. Her love affair with the Tigers had not prevented her from marrying a devotee of the Chunichi Dragons, the team in Nagoya. Their intermarriage produced a son, now 14, who has chosen the Tigers.

“He’s a good boy,” Katsura said with the unmistakable tone of a victor.

Other good boys sat throughout the section. They wore school uniforms and filed down the aisles to their seats with the correctness of parliamentarians shuffling into session. Despite their formal clothes and posture, they were having fun. But they were not just any students on a school trip. They were all survivors of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that triggered the Fukushima nuclear accident. The Swallows had brought them as special guests, and when they were announced on the P.A. between innings, the entire stadium, including the players, stood and cheered.

There was something quintessentially Japanese about the experience. The baseball stadium is where harmonious, courteous, rule-abiding Japan lets down its hair. Almost from the beginning, when an American missionary named Horace Wilson introduced the sport here in 1872, Japan adopted baseball as its own. As one Japanese writer put it, “If the game hadn’t already been invented in America, it would have been invented in Japan.” But the ballpark here serves other purposes, too: It is a cultural inheritance transmitted through bloodlines, a meeting spot, and, as I would discover soon enough, a place of emotional refuge.

Day 2: Osaka-Koshien

My friend Shutaro Suzuki, a devoted member of the Swallows’ fan club, insisted that I see Osaka’s team, the Hanshin Tigers. “They are the most crazy!” he told me. So I boarded the Shinkansen, aka the bullet train, west to Osaka. The train is state of the art, with airy compartments redolent of leather that offer an ideal vantage from which to watch the landscape of coastlines, forests, and mountains streak past.

The Tigers’ field, Koshien, has special meaning to Japan because it hosts a two-week, 49-team school tournament that, each year since 1915, has crowned a national champion. Tigers fans were certainly colorful, many in black and yellow, with tiger masks, tiger whiskers, tiger socks, and tiger tails. Some had dyed their hair with streaks of yellow. I took my seat in center field. No one around me spoke English, but once they saw I was an ally — as a matter of baseball-travel policy, I always root for the home team — they offered me cold chicken tempura and whiskey highballs, and high-fived and fist-bumped me. When the Tigers chased the opposing BayStars’ pitcher and the fans bid him sayonara with “Auld Lang Syne,” I sang along, even though everyone else was singing in Japanese.

Outside, I found Koshien’s monument to Babe Ruth, a plaque set in a block of stone mounted in a pavilion. Ruth played here while leading a legendary 1934 tour of American all-stars across Japan. It was a spectacular success and critical event in the history of Japanese ball, helping launch the country’s professional league two years later.

“Ruth was very important to Japan,” Robert K. Fitts, author of Banzai Babe Ruth, a superb history of the tour, told me. “He was the most popular athlete in the world. He was like Muhammad Ali. The Japanese considered amateur ball as pure, and professional as tainted. The Ruth tour showed it could be honorable. It also showed the economic potential.”

Japan was good for Ruth, too. His skills were in decline, his career drawing to a close. But in Japan, he magically found his swing, and his youth, again, mashing 13 home runs in 18 games. Crowds lined streets serenading, “Banzai Beibu Rusu!”

Ruth even shared his hosts’ fantasy that the tour would restore deteriorating U.S.-Japan relations. He returned to America full of optimism, his trunks packed with rare Japanese objets d’art. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor seven years later, he opened the windows of his apartment above New York’s Riverside Drive and pitched the Japanese treasures one by one onto the street below.

The disaffection was mutual. For the Japanese, banzai turned into a different kind of rallying cry. Their soldiers in Burma were said to have charged into battle screaming, “To hell with Babe Ruth!”

Day 3: Hiroshima

My next stop was Hiroshima, where the war ended when American bombers silenced those battle cries and really sent this Japanese city to hell. It is, somewhat incongruously, a cheerful place of 1.2 million people. It has wide, busy streets, pedestrian-only districts with fashionable boutiques, artsy cafés and teahouses, good restaurants, a red light district that has become somewhat standard in large Japanese cities, and an expansive public park along the Ota River with striking sculptures and statues recalling that it was here that, on the morning of August 6, 1945, in a hot flash of light, 140,000 lives were extinguished, with tens of thousands more perishing later.

Hiroshima’s team, the Toyo Carp, was off for the week, but I wanted to see the city, which had risen from the ashes, a revival in which baseball played a role. Even after the war, the Japanese never considered abandoning their American sport. On the contrary, they seemed to embrace it even more warmly. In 1946, the Japan Baseball League resumed play and, in 1949, announced an expansion from 8 teams to 12. Hiroshima wanted a squad, but the city was so devastated and impoverished that it couldn’t attract one of the corporate sponsors that typically fund Japanese teams. So its people raised a campaign, collecting public donations, and in 1950 fielded a team on their own. The city named the team for the abundant koi in the Ota River, but chose the English word, carp. Another name that was considered was the Atoms.

I visited the A-Bomb Dome, the former Hiroshima Prefecture Industrial Promotional Hall near ground zero that somehow withstood the blast, before arriving at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The opening exhibit is a diorama of three figures — a woman, a girl, and a boy — their skin hanging like wax from their bones, an exact depiction of physical torment not even imagined by Dante. All of the exhibits were unspeakably sad, but perhaps none more so than the tricycle beloved by a 3-year-old rider who perished. His father, feeling the boy was too young to be left in the cemetery by himself, had buried him in his backyard with the tricycle. A dozen years later, when the boy’s remains were finally interred in a cemetery, the tricycle was moved to the museum.

“It’s a myth that people were vaporized,” a docent named Kumiko Seino told me matter-of-factly. “They were carbonized. Their bodies were burned black, like hard wood.” During the recovery, the Ota quickly filled with corpses. A lack of equipment made burial difficult; a lack of wood made cremation equally challenging.

Kumiko was one of the museum’s “memory keepers,” who share their experiences as hibakusha — survivors and children of survivors. One reason she began volunteering was that it pained her how often she met young Japanese who knew little about the bombing. “They think the bomb fell in an open park,” she said. “They don’t realize it was filled with people and it’s a park now because they were all destroyed.”

She took me to the Peace Bell and the Children’s Memorial and into the basement of a building where I had to put on a hard hat. A worker had survived here, protected by the concrete despite being only a little over 500 feet from ground zero. In one corner was a senbazuru, 1,000 origami cranes on string. It’s a way of lighting up the space and showing that people remember. Little else seems to have changed. A steel door is still canted on its hinges.

Kumiko walked me around the Peace Park, showing me different cenotaphs — monuments to families that once lived here. “Takada’s wife and children,” said one. “Takagi and his wife,” said another.

“Sometimes I feel I am coming to see my grandmother,” Kumiko told me. “I don’t like to come at night. Maybe there are ghosts.”

“Why ghosts?”

“Because they don’t go to heaven. They died so quickly they didn’t know they were dead.”

I don’t believe in ghosts myself, but in meeting Kumiko and others, it wasn’t hard to see how the living people here could be haunted. Hiroshima is full of people born after the war who were their parents’ second try at life. I encountered no bitterness; on the contrary, Kumiko was careful not to make visitors uncomfortable. What happened happened, there was no going back, and Hiroshima’s mission as a city has become to make sure it never happens anywhere else.

Later, I walked down a side street and slipped into a plain but appealing little restaurant. Two men signaled that a seat next to them at the counter was free. Hironabu and Hiroyuki, both 61, spoke limited English, but between hand gestures, nonverbal cues, and a translation app, we passed an evening of remarkably wide-ranging conversation. I bought them a round of shochu; they reciprocated with a round of chicken meatballs. I got a lesson in restaurant Japanese: Yaki means grill and tori means bird. To help me understand what I might be ordering, they patted body parts. Behind a glass panel, the chef-owner turned skewers over hot coals with the attention of a surgeon performing an organ transplant. Which, in a sense, was what he was doing.

“Kidneys?” I asked. “You have two?”

“No! One!” he said. “Shio kimo.”

I offered other possibilities — heart, stomach, intestines. “Oh, I know,” I said. “Liver!”

“Yes! Liver!”

We ate atsu-age, thick cuts of deep-fried tofu, lotus root, and shiitake mushrooms. “Shiitake!” Hironabu said, and was overjoyed to learn we use the same word in English.

Their parents were survivors. Both men were born in 1955, 10 years after the event. Like Kumiko, they represented the city’s reissue, its rebirth, but neither of them had ever discussed it with his parents. It was just there in the background. There were other things to talk about.

“You play baseball?” Hironabu asked.

Yes, I told him, I played third base in high school.

“He,” Hiroyuki said, pointing to his mate, “center field. Me, I watch.”

“I was no good,” Hironabu confessed.

“Me neither,” I said.

“You know the Carp? They are the number-one team! The best team!”

We drank to that.

On the way back to the hotel, I stepped into a 7-Eleven, which had copy machines that also allow you to order and print baseball tickets. Everything was in Japanese, but it was easy to get a store clerk to help. The next day, I planned to go to Fukuoka, the largest city in Kyushu, the westernmost large island of the Japanese archipelago, to see another game.

Back in my room on the 10th floor of my hotel, I lay on my back and closed my eyes. A little later I felt myself swaying, and for a moment wondered if I’d drunk more than I’d realized. As the bed began to swing like a hammock, I gripped both sides of the mattress and held on until the earthquake passed.

Day 4: Fukuoka

The Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks can play indoors when they need to — the Yahuoku! Dome, completed in 1993, was Japan’s first retractable-roof stadium — so the one thing I hadn’t worried about was being rained out. I couldn’t have anticipated an earthquake. In fact, it was a whole series of earthquakes, dozens of them, foreshocks and aftershocks sandwiching the main event, 7.3 on the Richter scale, that I’d felt all the way back in Hiroshima. Dozens died, at least a thousand were injured, and many tens of thousands found themselves without shelter.

Further spasms buckled highways and bridges. But the trains to Fukuoka were still running, so I decided to stick to my plan. When I checked in to my hotel, I got evacuation instructions along with my keycard. TV reports showed emergency workers freeing trapped victims and carrying zipped yellow body bags. Officials spoke with tight, grim expressions.

The first game after the earthquake was canceled, but the second took place as scheduled. Waves of people came out, filling the stadium. I had expected some kind of pregame acknowledgment, a moment of silence at least, but at 1:00, the SoftBank Hawks unceremoniously took the field and the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles’ first batter stepped to the plate.

The first seven innings featured some of the dullest, most error-ridden baseball I’d ever seen, as if after a tragedy of great magnitude, no one’s heart was really in it. Although the fan club in right field tried, even they had a certain forced feeling. Finally, with the listless Hawks down 7-3 and showing no signs of life, I decided to leave. I visited the Sadaharu Oh Museum, which celebrates the life and career of the man known as the Babe Ruth of Japan, and the team shop before catching the bus back to the city center. Somewhere along the way, I had the sudden feeling something was amiss. I patted my pockets and checked my satchel to confirm the loss. My Japan Rail Pass was gone. You could only buy it outside the country, and you needed to keep the physical pass on you. I was a bit ashamed to feel as aggrieved as I did given the devastating loss the people here had just suffered, but it was expensive, and I’d have to pay full fare to get back to Tokyo, so I decided to go back on the off chance I’d find it.

An hour had passed since I’d left when I got a taxi to go back, but the driver still had the game on his radio.

“The Hawks are still playing?” I asked.

He eyed me in the rearview mirror. “Tie,” he said. “Seven to seven.”

The Hawks had scored four times in the bottom of the ninth. I dashed back into the stadium, where the fans who’d stayed were on their feet waving rally towels and a team band banged taiko drums and blew horns as the teams slugged it out in extra innings. The Hawks were down to their last out in the bottom of the 12th (in Japan, games are declared a tie after 12 innings) when their 32-year-old outfielder Yuki Yoshimura, whose three-run pinch-hit homer in the ninth had evened the score, hit a walk-off blast to win the marathon contest.

Mic’d up in the outfield, Yoshimura addressed the fans. Japan calls these postgame exchanges the “hero of the game” interview. The whole place was silent as he spoke. A woman next to me translated, though I hardly needed her help.

“I know I’m just a baseball player, and we can’t do much,” Yoshimura said, “but we know the people of Kyushu are suffering and they won’t quit, and we were never going to quit, either.”

I admired him for being able to speak even more than for what he’d done in the game — though later, when a television reporter asked him a question, he covered his face in his palms and sobbed.

It put the loss of my rail pass in perspective. Still, after the stadium exploded fireworks that reverberated dreadfully under the closed dome, and after the fans performed the ritual of releasing oblong yellow balloons in the air, so symbolic of letting it all go, I decided to check the lost-and-found — because you never know.

And, this being Japan, someone had, of course, turned it in.

Originally published on Travelandleisure.com.

Todd Pitock’s last piece for the Post was “A Discouraging Word” (Argument, May/June 2017).

This article is featured in the March/April 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

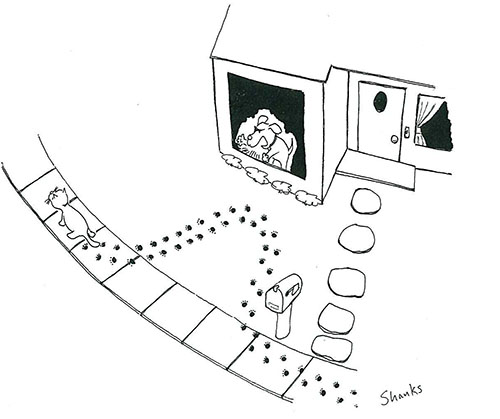

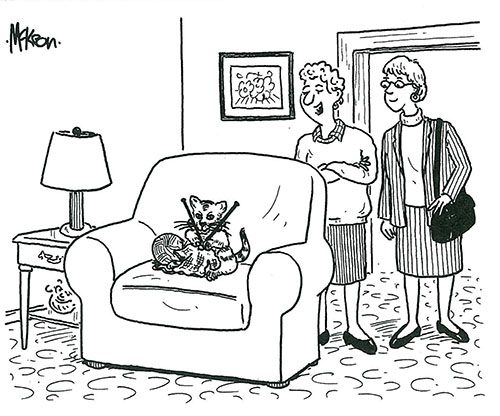

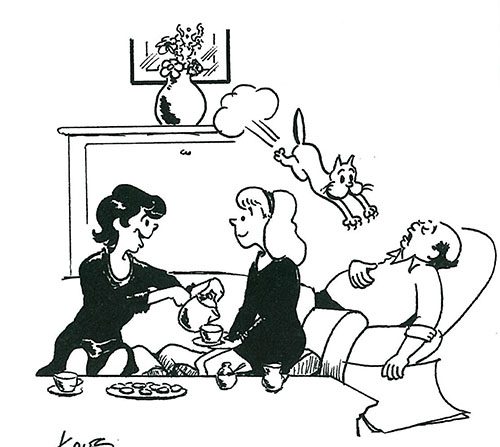

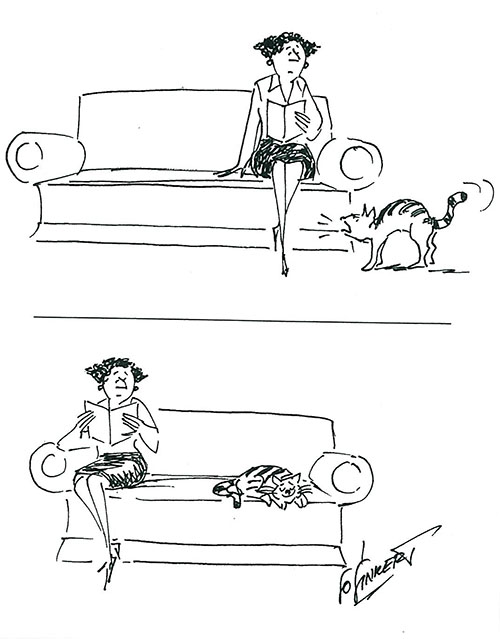

Cartoons: Favorite Cats

Holy cats! Check out some of our best cat cartoons.

Nov/Dec 2001

Jul/Aug 2002

Sep/Oct 2005

July/Aug 2004

Jul/Aug 2004

Mar/Apr 2009

A Centennial of Cultivating Character in Pennsylvania

Sixty-six years ago, James Tate rose at 4:30 a.m. sharp each morning to milk a handful of cows in time for his 6:30 a.m. breakfast. This strict routine taught him responsibility and work ethic as a teen. Through pouring rain, headaches, and unruly sows, Tate learned “the cows always have to be milked.”

Tate didn’t grow up in the Midwest or even in a rural area; he attended the Church Farm School just 20 miles outside of Philadelphia.

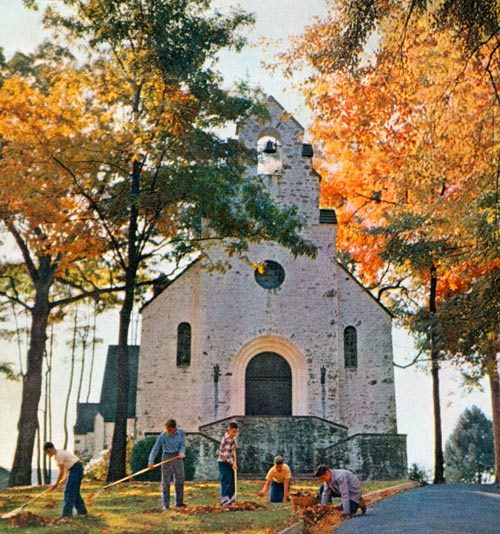

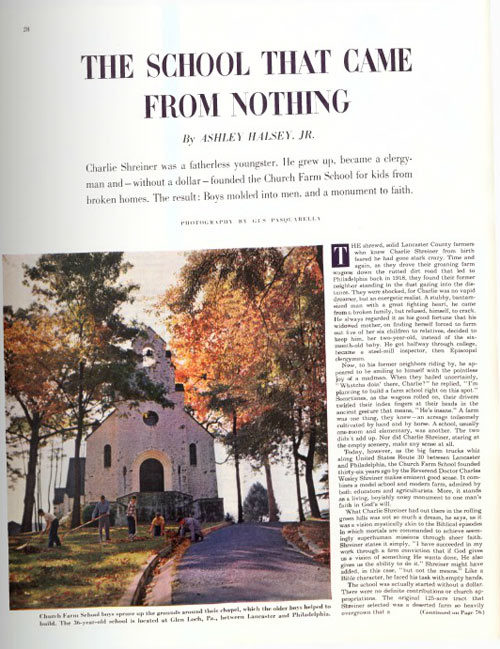

The Episcopal boarding school for boys is celebrating its centennial in April. Although dairy farming is no longer a part of the curriculum, CFS continues its focus on disadvantaged boys that was the subject of a 1954 article in this magazine titled “The School that Came from Nothing.” Ashley Halsey, Jr. reported for the Post on the humble origins of CFS and its eccentric brand of education. More than 60 years later, the ambitious “school that came from nothing” remains the legacy of one man’s wishful thinking that worked.

The school was founded by Charles Shreiner, a stern Episcopal priest dubbed “the Colonel” by his earlier role in a Pennsylvania Boys’ Brigade. To realize his dream of opening a school for fatherless boys — as he had been himself — the Colonel cozied up to Philadelphian philanthropists and set out to work on his 125-acre plot in Glenloch, Pennsylvania. Over the years, the farm grew in serendipitous strokes: oil and electric companies paid to cross the land with their pipelines and power lines, and confident donors filled out the operation with tools — both educational and agricultural.

At its largest, the Church Farm School spanned 1,600 acres and raised cows, chickens, and hogs along with a host of crops. The bulk of the farm’s products were sold to sustain the school, and some of the bounty was packaged as gifts for its faithful benefactors. Tate recalls the peony bouquets and sausages the boys prepared to send off as tokens of thanks. If a donor was lucky, they might receive a parcel of scrapple in the mail. The pork by-product has fallen out of fashion, but in the ’50s Tate and his fellow farmers skimmed the fat from the mush and wrapped it up as “Church Farm School Scrapple.”

The school’s scrapple days are over. In the 21st century, CFS engages its students in STEAM (Science Technology Engineering Arts and Mathematics) learning. Reverend Edmund Sherrill took the helm of CFS 9 years ago following three generations of Shreiner leadership.

Since the last write-up of CFS in this magazine in 1954, the school has transformed into a diverse community of hands-on college preparation. In the student body of around 200 boys, Sherrill says 80 percent are students of color, and the school has boasted a 100 percent college admission rate for seven years. “I have to believe that the founder would be pleased that the school’s mission is intact,” Sherrill says, “to bring opportunity to kids who wouldn’t otherwise be able to access it.” Eighty-eight percent of the school’s students receive financial aid.

Mohammed Emun graduated from CFS in 2017. He refers to the school as “the farm” even though the four silos that watch over its campus no longer hold grain. Emun attends Tufts University in Massachusetts, and he is planning to combine his interests in computer science and psychology to study cognitive brain science. Emun says his days at the farm were filled with challenging coursework, multidisciplinary extracurriculars, and community service. “I see some other students having a hard time adjusting to college, but I think it’s easier for me since I learned independence at a boarding school,” he says. Emun left his home in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania to attend boarding school at age 11. While at CFS, he edited the school’s yearbook, took part in student council and multicultural club, and even volunteered with Habitats for Humanity.

In its century of growth and transformation, CFS has come to focus on maintaining a small student body — around 200 boys — and developing an arts-integrated education in an effort to create global citizens. “Curriculum has changed from the delivery of information to the utilization of information,” Rev. Sherrill says. By blending arts and design into a STEM education, Sherrill believes the school’s curriculum is addressing the larger questions behind utility and function, like, “What kind of world are we designing to live in?”

Creative problem-solving has a long history at CFS, starting with the Colonel’s bureaucratic backflips that kept the school running through world wars and the Great Depression. The still-standing 1928 gothic-style chapel was erected with the help of some of its pioneering students, who carved the lumber and laid the stone for the structure. While agriculture was a focal point in the earlier days of the school, for some it served only as a larger lesson in accountability.

James Tate spent years milking cows and cutting corn when it was “high as an elephant’s eye,” but he didn’t go on to a career in animal husbandry. Tate graduated from Penn State with a degree in liberal arts, and found himself in an advertising career in New York City by the late ’60s. Even after running his own advertising firm, he never forgot his time at CFS. Tate served as the president of the school’s alumni association for 20 years, and he now resides about 10 miles from campus.

Tate is pleased with the direction of the school as it enters its second hundred years. He believes the changing curriculum is necessary in a 21st-century world. When he steps onto campus, the changes are obvious: baseball fields and tennis courts have replaced pastures, and farmland has given way to a solar panel farm. What endures, however, at CFS is the attitude of the boys toward their school: “I am amazed at how strongly they feel about the school when I see them on campus,” Tate says, “They talk about it in glowing terms.”

North Country Girl: Chapter 45 — That Toddlin’ Town

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

On my second day in Chicago, James took me in his big Cadillac to see an apartment he was thinking of renting. Newberry Plaza was a brand new high-rise building that looked surprised to find itself towering above the single-story restaurants, bars, and shops of its Near North neighborhood. As we entered the building, we passed a new restaurant on the main floor, and, James, always one to be impressed with celebrities no matter how minor, said, “That’s Arnie’s Steak House. It’s owned by Arnie Morton, the guy who bankrolled Hugh Hefner.”

A man at the lobby desk checked James’ name, made a phone call, and a pretty young thing in a pastel suit showed up and gave us the questioning eye I had almost grown accustomed to. She was like all the people we saw in the lobbies and elevator: youngish, well-dressed, and attractive. I sensed James’ relief that there were no disgusting old people living here.

Newberry Plaza apartments were designed for happening singles, all one-bedrooms and studios, a place within staggering distance of Chicago’s most popular bars and clubs. At fifty-seven stories, it was the tallest building I had ever been in. The rental agent showed us into a boxy, ordinary apartment that was not as big as James’ place in Des Moines; bedroom, living room, bathroom, and a kitchen designed for people who never cooked. James gushed, the woman beamed, and I shrugged till I looked out the window. Down below was a sparkling outdoor pool surrounded by rows of white lounge chairs. A private pool in downtown Chicago seemed improbably luxurious.

“What do you think?” said James, with his tell of a little self-satisfied smirk. I assured him that I thought Newberry Plaza was really cool, and I could see him living there. He agreed, already mentally escaping from his tacky two-story, half-brick half-gabled refuge of the dental assistant and divorced dad, a building that put the plain in Des Plaines. He was moving to the heart of toddling Chicago. James signed a lease that day for a one-bedroom apartment on the 10th floor at what seemed to me the astounding sum of $400 a month.

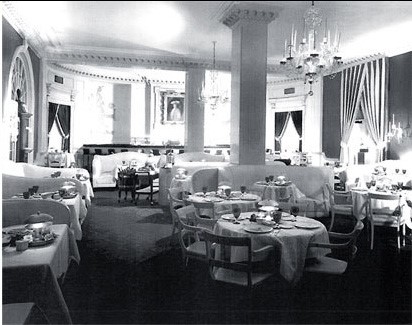

That evening I discovered that the real selling point for Newberry Plaza was that it was three blocks from James’ preferred backgammon den, in the Ambassador West Hotel, which was every bit as posh as it sounds. A uniformed doorman, unsmiling as a Beefeater, nodded at James before allowing us to enter the hotel. James confidently guided me through the hushed, dimly lit lobby, where visiting dignitaries murmured to the concierge. I suddenly realized that I was wearing the same outfit I had on when I was given the bum’s rush out of the El Presidente hotel; I hoped there were no house detectives lurking about as I scurried beside James in my platform shoes and mini skirt like a furtive hooker.

The backgammon club was hidden inside the hotel. There was no sign, only a discreet door in the back of the lobby. When I walked in, I felt as if I had entered a scene from Dickens, a London club frequented by Mr. Pickwick or the three gentlemen who declined to attend Scrooge’s funeral unless a lunch was provided.

The walls and upholstery were all deep maroon, the color of claret. Dark wood paneling was punctuated by sconces, which emitted a golden light that was calming and flattering. Hunting prints depicting horses and dogs and men in pink hung evenly between the sconces. The place was as quiet as a library and smelled like money.

The eight backgammon tables were all occupied, mostly by older white men who looked like bankers, but there was also a man who was even darker than James with a nose like a knife, smoking a black cigarette, playing against a raven-haired woman who was the same age as my mother but half the weight, a woman who sparkled about the neck, wrist, and fingers, her diamonds catching the light like tiny disco balls. James and I sat at the carved mahogany bar, the rich relation of the one at Pracna. Without a word, the bartender placed a vodka and soda, the least fattening of drinks, in front of James. The bartender tilted his chin at me and I reluctantly agreed to have the same.

One of the older gents sighed, took out his checkbook, shook hands with his opponent, and left the club. James walked over to the empty seat, and after an exchange of raised eyebrows and hand signs, sat down to play. I watched James roll the dice and march his men around the board and felt that another rabbit hole had opened up, transporting me to a new Wonderland. I leaned back in my comfy bar chair, yanked down my miniskirt, and tried to talk myself into feeling I belonged there, despite the fact that bets the equivalent of my entire shoe box of tips were changing hands every few games. There was no music, the waiter silently and automatically replaced empty glasses, and few words spoken besides a soft “double”. The loudest noises were the chunk chunk of the dice in their cups and the swish of a cocktail shaker. It was very soothing, being tucked away in this jewelry box, and I started to relax as I sipped my disgusting drink. But Houdini James had other things up the sleeve of his suit jacket, a jacket the backgammon club required men to wear (women were not allowed to wear pants, and my tiny skirt got a few disapproving looks).

Backgammon had always been an endurance sport for James. Whole afternoons and evenings would pass in marathon games at the Villa Vera before James would pack away his backgammon board. I was settled in at the bar for what I thought would be the rest of the night when James stood, collected his winnings, finished his drink, and escorted me out of there.

Astoundingly, there was another meal, this one right across the street at the famous Pump Room. This was the absolute cherry on this sundae of a weekend, as my idea what a fancy big-city restaurant looked like had been formed when I first saw a photo of the Pump Room in my mom’s Time–Life cookbook, and it seemed unchanged ten years later. Red-jacketed waiters lifted silver domes, boned Dover soles, cracked eggs and grated cheese over Caesar salads. As waiters pulled out my chair, before me was a wide, empty plate, guarded on both sides by rows of heavy silver knives, spoons, and forks of various sizes. Our waiter whisked away that empty plate and then solemnly opened a bottle of champagne, deadening the pop of the cork with a thick white napkin.

Over more food (I was starting to feel like a Strasbourg goose) the old James came back. He rehashed the night’s backgammon games, giving himself extra points for his luck, daring, and ability to quickly and logically assess potential dice throws. I was once again in my supporting role as admirer and eager student, James quizzing me on odds, probability, and back game strategy.

The clock struck midnight, and in Chicago as in Acapulco, it was time to disco. James’s new apartment was a stumble away from Faces disco, where a long line of hopefuls stretched down Rush Street waiting to get in. James, of course, was welcomed at the door by a large man who slapped him on the back as James slipped him a folded up bill.

Six months before, Faces would have left me agape. But after the glories of Armando’s, I thought the place looked second rate, like a TV commercial set for “K-Tel’s Greatest Disco Hits.” The crowd was pale-even-in-summer swinging Chicago singles, the men in shiny Huk-a-Poo shirts and the women in dresses made of even shinier synthetics and sporting early variations of Farrah Fawcett’s famous feathered hair. The gaudy clothes were the only spots of color. Faces was all urban greys and blacks, and you had to feel your way down to the dance floor, which lit up in flashes, as if sending out a mysterious Morse code message. A fog-machine enveloped the club regularly, and the dim lighting and the strong drinks probably made for many regrettable pick-ups. Faces had cloned the soundtrack from Armando’s; we were still push pushing in the bush and rocking the boat, don’t rock the boat, baby, which blasted at ear-popping volume. A cute cocktail waitress found her way in the dark to our table. She gave James a hug and kiss and me a side eye that let me know they had slept together.

I was stuffed to the gills with continental cuisine, but when James stretched out his arm I heaved myself out to the dance floor to join the disco revelry. We danced till closing, then James, a steady hand on the wheel even with champagne and many vodkas in him, drove us back along the empty Chicago highways to his Des Plaines apartment, where we stayed in bed till my plane left the next day.

Chicago wasn’t as glamorous as Acapulco, but that weekend beat the hell out of slinging burgers and fighting with Steve in Minneapolis. And along with the copious drugs and sex, I enjoyed how different James had been with me. He still loved playing Svengali, guiding and grooming his wide-eyed young girlfriend. But for the first time I felt that James had listened to me, asked my opinions, treated me almost like an equal.

James always got a thrill out of kissing and stroking me in public, but our goodbyes at O’Hare were so uninhibited that every time I came up for air I saw another passenger staring at us. James held me tightly in his arms, until everyone else had boarded; I had to push myself away and run down the ramp to the plane, the door shutting behind me. On the flight home, I imagined how cool, how fun it would be if James flew me down Chicago once a month for backgammon, disco, and salami and eggs.

With nothing but this thought in my silly little head, I took a cab from the airport to Steve’s place. I wasn’t expecting a warm welcome. Steve let me into the apartment without a word and went back to his beer and whatever he was watching on TV. With a twinge of guilt, I started to tidy up the debris of what looked like a three-day party. I emptied the overflowing ashtrays and found several different shades of lipstick-traced cigarette butts and roaches. It seemed Steve had also had a fun weekend, although you couldn’t know it tell from his sullen pout.

I finally realized, “I can’t stay here.” I told Steve that I would pack my things and get out, and got a noncommittal grunt in response. I would make Patti and Mindy take me in for a few days, then make my apologies to Liz, hoping she needed a roommate for the fall semester. I walked out the door the next morning with my pink Samsonite suitcases. I didn’t see Steve again for seven years.

How did we find each other before cell phones and the Internet? (And how can you lose anyone now?) James somehow tracked me down at Patti and Mindy’s. As I dabbed off ketchup stains from my Pracna uniform I listened to James’ husky voice on the phone, telling me he had never met anyone like me and asking me to move to Chicago to live with him in his cool new downtown apartment. He didn’t say anything about love. I didn’t care.

At this point, five years after my first disastrous experience, which I had come to think of as “the moonshot,” I had learned that sex and love did not necessarily go together. They had with my first love, Michael Vlasdic; we were drenched in Lysergic acid diethylamide and teenage hormones, and sex was our souls touching. But with the right guy, sex could be about friendship, a chance to laugh and play and say “I really like you.” With Steve, the wrong guy, bed was a battlefield and sex was about control and craving and power, who was on top, who was under the thumb. With James sex was the floor of the mercantile: my bouncy flesh and boundless curiosity traded for his depth of experience and wealth of knowledge. It was an exchange so satisfactory to both of us that Adam Smith would have approved.

If James’s offer had been to move me to stodgy, suburban Des Plaines, I would have balked. But at that point, I was a gypsy with little to hold me in Minneapolis: I was sleeping on a couch and living out of a suitcase. I said yes.

Considering History: Vitriol and Violence, Radical Activism, and the Suffrage Movement

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

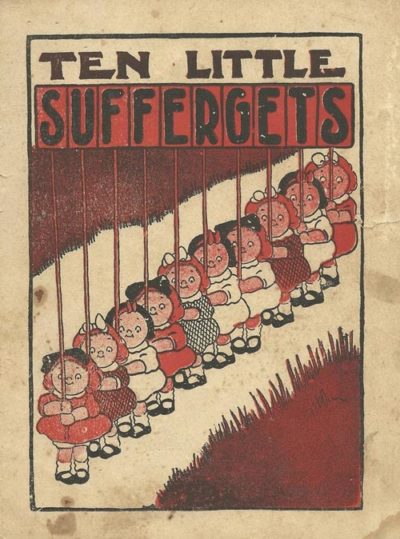

The early-20th-century children’s book Ten Little Suffergets (c.1910-1915) literally and figuratively illustrates the vitriol and violence often directed at the women’s suffrage movement and its participants. Based on the racist nursey rhyme “Ten Little Indians,” the book portrays suffrage activists as a group of spoiled young girls, carrying signs demanding such changes as “Cake Every Day,” “No More Spanking,” and “Down with Teachers” alongside “Equal Rights.” One by one the “suffergets” are either distracted by frivolous pursuits and abandon the cause or are violently removed from the march (such as by an angry father figure). The concluding image is of the final girl’s abandoned “dolly” (looking quite like the girl herself) with a cracked and broken head.

It’s possible in hindsight to see a now broadly accepted cause like women’s suffrage as being widely accepted and shared, as a significant political change that took time to achieve but without the kinds of hostile responses other such social movements have received. But in fact, across its more than half a century of existence, the American suffrage movement was quite the opposite: a profoundly radical and progressive idea that was subjected relentlessly to both rhetorical and actual attacks. Remembering those attacks always helps us consider the consistent courage of suffrage activists in facing such harassment and arguing for their cause, often in the most public places and ways.

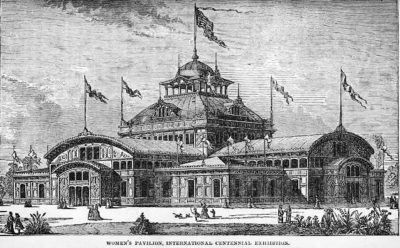

The July 4, 1876 protest at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia was one such occasion. For the first time at a World’s Fair, the Centennial included a separate Women’s Pavilion, a space in which to celebrate and share women’s identities, art and culture, and voices. Yet this impressive step was not without its limits, and one was the near-complete absence of any social or political issues — including the era’s most prominent such issue, suffrage — from the pavilion. Indeed, focusing more on domestic arts and crafts and housework, the Women’s Pavilion could be said to reinforce some of the most prominent arguments against women’s participation in the public and political spheres.

A group of suffrage activists, representing the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), decided to highlight this exclusion and their cause at the Centennial’s most public occasion, the July 4th celebration. Led by Susan B. Anthony, the group erected a stage of their own not far from the celebration’s official platform, and there read aloud a “Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States” (a revision and extension of the declaration produced at the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman’s Rights Convention). Before doing so, Anthony made clear the group’s willingness to confront their fellow Americans in this most public space, noting, “While the nation is buoyant with patriotism, and all hearts are attuned to praise, it is with sorrow we come to strike the one discordant note, on this 100th anniversary of our country’s birth.” Yet she added, “Our faith is firm and unwavering in the broad principles of human rights proclaimed in 1776, not only as abstract truths but as the cornerstones of a republic.”

Anthony, the NWSA, and their many colleagues continued to strike their discordant note and fight for the extension of those rights for the next four decades. Another very public moment of radical activism, and one met with particularly violent response, was the March 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade. Held in Washington, DC, on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, the parade represented the largest gathering of suffrage activists and allies in American history, with more than 5,000 participants marching down Pennsylvania Avenue.

The marchers were met with sustained hostility, not only from many in the crowd but also from at least some of the police officers tasked to protect the parade. Hundreds of marchers were seriously injured; according to one eyewitness testimony quoted in The Washington Post, two ambulances “came and went constantly for six hours, always impeded and at times actually opposed, so that doctor and driver literally had to fight their way to give succor to the injured.” Yet the marchers, led by prominent activist Alice Paul and attorney Inez Milholland (riding a white horse), persevered, completing their planned route from the Capitol to the Treasury building, and drew national attention to both their cause and the violent attacks upon it.

The parade also featured an internal discordant note that produced one more moment of radical courage. The organizers intended the march to be segregated, with a separate cohort of African-American suffrage activists bringing up the rear. The pioneering journalist, anti-lynching crusader, and women’s rights activist Ida B. Wells asked if she could march with the Illinois delegation in the main march, and was initially turned down. Yet Wells did not accept this answer and, with the aid of sympathetic allies, defied this racist division and joined the Illinois delegation as the march began. In so doing, Wells embodied one more moment of radical persistence in the face of contempt and exclusion, a historical lesson that the American suffrage movement offers consistently and crucially.

Con Watch: Getting Something for Nothing on Twitter

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

An estimated 157 million people use Twitter each day, so it isn’t surprising that scammers have used Twitter for years to perpetrate scams. The latest Twitter scam is both simple and ingenious.

The scam begins when a thief impersonates the Twitter account of a prominent person with a lot of Twitter followers. They will use an identical photo and choose a Twitter handle that looks similar to the real thing. For instance, Elon Musk’s legitimate handle, @elonmusk, was impersonated by someone using @elonlmusk (with an l). Someone glancing at the scammer’s tweet might not recognize that it is not the Twitter handle of Elon Musk.

In this case, the scammer tweeted, “I’m giving away 5,000 ETH to my followers! To pаrtiсipаte, just send 0.5-1 ETH to the address below and get 5-10 ETH back to the address you used for the transaction.” (ETH is an abbreviation of the cryptocurrency Ethereum.) Victims then send the cryptocurrency in an attempt to receive more in return. Obviously, the real Elon Musk isn’t involved and — surprise! — the victims never get their money.