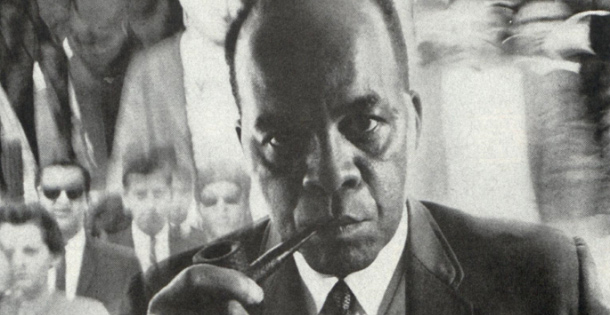

In his long — yet widely forgotten — fight for civil rights in Washington D.C., Julius Hobson was rarely predictable. The Social Security Administration economist and statistician took on many roles in the 1960s and ’70s in the struggle for racial equality. Hobson was an organizer, a professor, a city councilman, and — perhaps most surprisingly — an FBI informant.

Hobson’s activism was characterized by gimmicky protests as well as pragmatic policy work. His most infamous stunt involved carting cages of giant rats to Georgetown from poorer D.C. neighborhoods in 1964. In his rallies, Hobson claimed he had a rat farm with many more of the vermin, which he threatened to release (legally) in wealthy, white neighborhoods if action wasn’t taken to curb the pest problem in poor black ones. “A D.C. problem usually is not a problem until it is a white problem,” he said.

In reality, no such farm existed, but Hobson’s hoax convinced the city to implement rat patrols in its Northeast and Southeast neighborhoods.

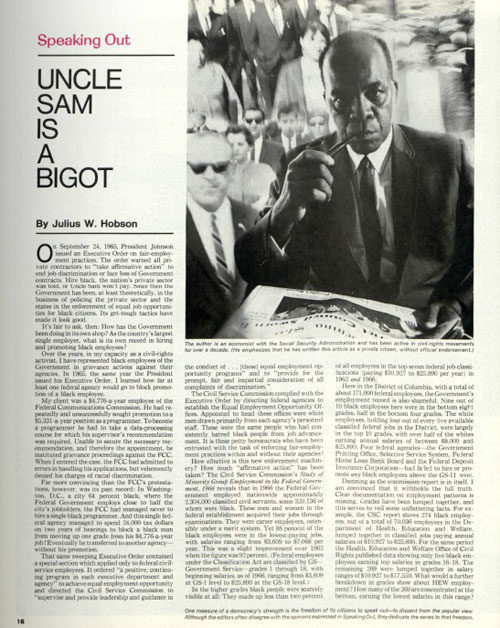

Hobson concerned himself with an array of issues affecting African Americans in D.C., most notably housing, education, law enforcement, and employment. Fifty years ago, Hobson’s editorial for The Saturday Evening Post, “Uncle Sam Is a Bigot,” addressed discriminatory hiring and promoting practices in the federal government. After President Johnson’s 1965 executive order demanding private contractors to “take affirmative action” against employment discrimination, Hobson turned a critical eye to the government’s own agencies and found significant disparities between the experiences of black employees and white ones. Furthermore, he encountered resistance from these departments to confront the issues despite mounting evidence of institutional racism.

Hobson described one grievance proceeding he took part in: “In Washington, D.C., a city 64 percent black, where the Federal Government employs close to half the city’s jobholders, the FCC had managed never to hire a single black programmer. And this single federal agency managed to spend 24,000 tax dollars on two years of hearings to block a black man from moving up one grade from his $4,776-a-year job!” Similar scenarios were to be found in the SSA and the Navy. Overall, he discovered that 88 percent of black federal employees were stuck in the lowest-paying jobs.

The Equal Opportunity Employment Commission, also established in 1965, was largely staffed, Hobson recognized, with the same white men from the personnel staffs of various agencies “who had consistently barred black men from job advancement.” Hobson believed the only remedy to this marginalization was for African Americans to make employment demands and to back them up with a lawsuit.

The litigation route had worked for Hobson the previous year. He had successfully sued the District of Columbia Public Schools to end their practice of “tracking” students according to skill level when he proved the schools were spending more money on white students than on black students.

Hobson died in 1977, but it wasn’t until 1981 that The Washington Post reported on FBI files claiming the self-described Marxist socialist had acted as an informant during the early and mid-1960s, once receiving between $100 and $300 for his work. There was no evidence suggesting Hobson had betrayed his activist community to the FBI, however. In fact, those who knew Hobson said he was likely misinforming the agency to throw them off. He was, after all, described in the FBI’s documents as “an undependable leftist radical who should be kept under surveillance.”

The best explanation of Hobson’s unlikely relationship with the FBI lies in his tendency toward nonviolent protest. Although he had reportedly given the bureau information in advance regarding large-scale protests — the march on Washington in 1963 and a civil rights demonstration at the 1964 Democratic Convention — Hobson often did so with the intention of constraining the more militant groups involved, like the Deacons for Defense and Justice and the Maoist black nationalist Revolutionary Action Movement, who advocated arming their members. A retired FBI agent, and a contact of Hobson’s, corroborated that the activist only divulged information to avoid violent confrontations and was never steered by the agency.

The whole narrative is further muddled by Hobson’s reputation for deception as a means to justice. His demands for equality at any cost cast a puzzling shadow on Hobson’s role in the civil rights movement. Perhaps he is best characterized by his catchphrase, according to his obituary in The Washington Post: “I sleep mad.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now