Veterans of the newspaper game whose memories of active affairs in print shops run back for so far as two decades should have no trouble in fixing chronologically the period when there befell the thing of which I mean to tell. For the time of it was the time when yellow journalism, having passed its pumpkin-colored apogee, was by slow gradations fading to a saffronish aspect. Mind you, I’m not claiming that it yet was not very yellow in spots, for in spots it was — and to a somewhat lesser degree still is — but generally speaking the severity of the visitation had abated, as though a patient, having been afflicted for a spell with acute jaundice, might now be said to be suffering merely from biliousness.

It still, though, was in the day of the signed statement; the day of the studhorse headline; the day when the more private a man’s affairs might be the more public they were made; the day when today’s exclusive expose would he tomorrow’s libel suit and day after tomorrow’s compromise out of court.

Oldsters of the craft will remember how the plague started, and how as a sort of journalistic liver complaint it spread through the country so that newspapers both great and small caught it and broke out with red ink, like a malignant rash, and with weird displays of pictures and type, like a madness. There were certain papers in certain cities which remained immune, for the owners of these papers being conservative men or having conservative clienteles — which came to the same thing — took steps to quarantine against it, so to speak, and thus escaped catching the disease. But The Daily Beam did not have to catch it; it was horn with it, the lusty child of a craze for sensation and a plague for freakishness. And Jason Q. Wendover, its owner, was its Allah; and Ben Ali Crisp, its city editor, was his prophet.

Behind his back his staff called him Ben Alibi; to his face they called him Chief. Ask any man who broke into big-town newspaper work along about the time, say, of the Spanish-American War if he recalls Chief Crisp; and then sit back and prepare to hear tales of journalistic audacity, of journalistic enterprise and of journalistic canniness, all of them smeared and drippy with the very essence of yellowness. If he knew how to suck eggs and spew the yolks abroad he likewise knew how to hide the shells afterward, a gift which made him all the more valuable to The Daily Beam and to its proprietor, as shall develop.

There was the time when the exposures about the treatment of the prisoners confined in the State Home for Wayward Girls at Wilfordshire first came out. Other papers were content to print page long accounts of the testimony offered before the commission of legislative investigators to whom the inmates one after another described how they had been triced up to their cell gratings with their arms drawn tautly above their heads and their feet barely touching the floor; and how for lesser breaches of discipline they had been balled and chained or ducked in ice-water baths or locked up for solitary confinement in sound-proof cubicles. It made good reading. Charges of cruelty in reformatory institutions always have made and always will make good reading. But the inspiration of Ben Ali Crisp carried him beyond the mere publishing of the testimony and the mere interviewing of the superintendent and the accused keepers. Any city editor worth his salt knew enough to send good reporters to the hearing and with spread and layout to play up what copy the reporters sent back from the town of Wilfordshire. What did Crisp do?

Here’s what: One morning he had Lily Simmons report to him at eight o’clock instead of nine, which was her regular hour for coming on duty. To quote the sporting desk, Lily Simmons was his one best bet as a woman special writer. She weighed about ninety pounds, was a stringy little budget of nerves and nerviness, and she drew down ninety dollars a week for the work she did, and in three years’ time wrecked her health doing it. Under the pen name of Nita Dare she wrote heart-interest specials about murderers and visiting royalties and socially prominent divorcees and other popular idols of the hour. Under the guidance of the seemingly slack but none the less rigid discipline of the trade she followed she went down in submarines and up in balloons and came back to the shop and wrote adjective laden accounts of her sensations and her emotions. To prove the perils of working girls in a great city she once had stood on a certain corner after dark and kept tally — for subsequent publication — of the number of men who accosted her between eight-thirty and eleven p.m. And by common consent she was the most gifted sob sister of her hectic journalistic generation.

At eight o’clock this day, pursuant to orders, she came. Crisp was waiting for her. He took her into a disused cuddy room back of the art department, where old drawings, photographers’ supplies and such like things were stored. Out of one coat pocket he hauled a pair of handcuffs and out of the other a clothesline. On Lily’s bony little wrists he locked the cuffs, ran the rope through the middle link of the chain connecting them, passed the rope over a stout hook set high in the wall and drew her up until her arms were stretched straight above her head and her heels cleared the floor. Then he made the rope fast against slipping and went out and locked the door behind him, leaving her there on tiptoe with her face against the plastering. He left her there until four o’clock in the afternoon. When he let her down she was in a dead faint, but came to in ample time to do six columns of regular Edgar Allan Poeish agony stuff, which under the screaming six-column caption “How it Feels to be Strung Up for Eight Hours at Wilfordshire, by Nita Dare,” ran in next day’s editions of the Beam and made the town sit up and take notice for a week.

Then — so the reminiscent veteran will probably tell you — there was the famous headline which Crisp wrote once upon a time. Only a headline it was, but it started a laugh which laughed a distinguished young profligate right out of the United States. Long after Mr. Chauncey Chilvers had hidden his diminished head in Paris, then the favorite refuge of the discredited wealthy American waster, and long after the girl he had expected to marry had married somebody else and divorced that somebody else and married again, folks still were grinning over what Crisp did on the day when one of his reporters brought in the tale. It had to do with a gorgeous reception at the home of the fiancée’s parents in Park Avenue, with the appearance of the prospective bridegroom in a condition which might charitably be described as confused; with his attempts, under the guidance of a shocked but sympathetic second man, to ascend a flight of steps to the gentlemen’s cloakroom on the second floor; with his abrupt somersaulting descent from the top step back down again to the main hallway of the mansion at the very moment when the young woman and her father had issued from the drawing room to welcome certain guests of the utmost social and financial importance; and with the final upshot, which was the summary expulsion of the disheveled and incoherent offender into outer darkness.

The yarn, as written, was exactly the sort of grist which suited the Beam’s news hoppers. So Crisp put it in wide measure on the front page and over it he ran in inch-deep Italics the top caption: How to Lose a Rich Bride.

And immediately below this he framed a sort of combination of headline, decoration and illustration which was copied from coast to coast, becoming in time a headlining classic. It was like this:

The heavy black types supplied part of the picture; the tumbling manikin did the rest.

Then there was the time when the Beam was pushing its campaign against alleged inefficiency in the police department, taking text for its most vehement preachments from the failure of the force to capture the notorious “Doctor” Sidney Magrue, proved murderer and fugitive, going at large with a fat price on his head and his photograph and printed description stuck up in every station house. Crisp hired a stock actor to make himself up as this badly wanted person. Thus disguised, the actor spent a whole day strolling about populous parts of town, occasionally inquiring a direction from a patrolman on post and actually winding up at dusk by walking into headquarters and making inquiry at the Lost Property Bureau touching on a fictitious missing hand bag. The tale of the experience being printed in full in next day’s Beam resulted in three things — enhanced reputation for the Beam, a raise in salary for Crisp and the loss of a lifelong job for Inspector Malachi Prendergast, head of the detective bureau.

There is a sequel to the tale of this coup which sometime will bear telling, but not here; it’s too long.

Crisp was like that. He saw the news and he raised it. If a rival paper saw the raise, matching enterprise against audacity, he went the other fellow one better. There were risks to be taken of course — risks of damage actions, risks of personal reprisal on the part of some hot-headed citizen who figured that in the Beam’s desire to print not necessarily what was true but what was interesting he had sustained an injustice which only might be alleviated by the blackening of eyes and the bloodying up of noses. But for such contingencies Crisp, like a wise general who never plans an offensive but he shapes along with it his defensive, was usually prepared. It was to this forearming instinct that he owed the play upon his middle name — the lengthening of Ali into Alibi — which the men in the city room employed in speaking of him when he was safely out of their hearing.

For example:

One day a solid-looking individual with the air about him of nursing a grievance almost as large as he was walked into the Beam building and asked that he might see the city editor. He was told to go up to the third floor and inquire for Mr. Crisp. Aboard a creaky elevator he ascended to the third floor, and having traversed a corridor that was heavy with the distinctive smell of every newspaper shop — a perfume compounded of old paper smells, fresh ink smells, stale paste smells and photography chemical smells of any age at all — he came at the far end of the corridor to an anteroom where a square-jawed attendant took down his name and inquired what his business might be.

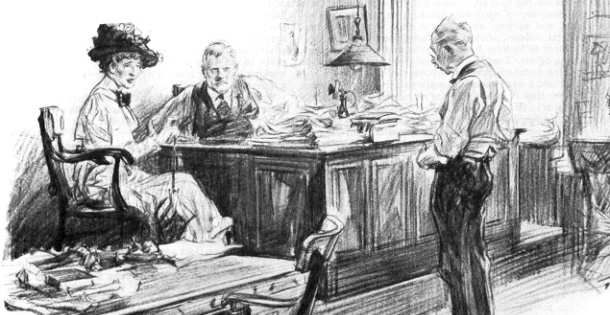

Now had this gentleman — Gillespie was the name he gave — been one of several common enough types that came to the Beam; had he been a crank seeking publicity for the exploitation of his pet fad, or an unfaithful servant desirous of peddling unsavory details of his master’s or his mistress’ private life for a price, or one of those unattached mercenaries of the newspaper game known as a tipster, he would have been bidden to take a seat upon a hard and uncomfortable bench and wait his turn. But Mr. Gillespie, it seemed, had come to demand redress and correction of a gross error deeply affecting him personally, which had appeared in the columns of yesterday’s Beam, and for such as he there was a standing rule designed by the owners with a view to proving how zealous was the Beam to render fairness to all. Hesitating only long enough to make up his own mind that the caller was the sort not apt to turn physically violent, the attendant summoned an office boy from within and promptly the gentleman was escorted through the city room, on past the copy desk and the battery of desks of the rewrite men, to where on a raised platform like a schoolmaster’s dais and behind a wide flat-topped desk that was bristly with steel spindles sat a prematurely grizzled man of forty or thereabouts.

At the stranger’s approach this man rose in greeting.

“Are you the man in charge?” demanded Mr. Gillespie, mounting the rostrum.

“Well,” said the other, “I imagine I’m the man you wish to see. I’m the city editor — Crisp is my name. And your name is — “

“Gillespie — James G. Gillespie, of Gillespie & Swope, wholesale carpets. Here’s my card.”

“Sit down, Mr. Gillespie, please.” Crisp waved to a chair which his personal office boy had shoved forward. “Now then, how can I serve you?” His manner was cordial but businesslike, in contrast to Mr. Gillespie’s, which was businesslike enough but stiff to the point of hostility.

“Well,” stated Gillespie, “you can begin by correcting this outrageous misstatement of facts which appeared in the last edition of your sheet yesterday afternoon.” And he laid on the desk before Mr. Crisp a crumpled clipping. “My partner says I ought to sue you people for libel. My wife, who is ill in bed as a result of this thing, says I ought to horsewhip somebody for it. But I decided that before I took any steps I’d come here to you and personally insist on an immediate retraction of this infamous error.”

“Quite right, Mr. Gillespie. You did the right thing. I’m glad you did come, though I’m sorry that such an errand should bring you. Pardon me one moment.” He glanced briefly at the clipping. “Now then,” he went on, “suppose you tell me the real circumstances in this affair? It says here — but suppose you tell me your side first?”

Mr. Gillespie told him at length and with heat. By his way of telling it there had been an incredible perversion of the truth. He had been put in an entirely false light; he had been held up to ridicule; he had been wounded in his general reputation; he had been embarrassed, humiliated, chagrined — and so on and so forth for five minutes.

When he had done Mr. Crisp spoke, and in his tones, his look and his bearing was a real distress hardly repressed.

“Mr. Gillespie,” he said, “first and foremost and before everything else we have two great aims in getting out this paper — to fight the battles of the people and to tell the truth. The truth hurts people sometimes — we can’t help that! We have our duty before us. But when meaning to do the right thing, as we always aim to do, we print something which turns out to be untrue it hurts us as a newspaper and it hurts me — personally — more than it possibly can hurt anyone else. I want you to believe me when I tell you this. And right here and now, before your eyes, I intend to make proper amends for unintentionally wounding you.”

“How are you going to go about doing that?”

“How are you going to go about doing that?”

“Just one moment, please, and I’ll show you.” He hailed the head copy reader. “Flynn, look through yesterday’s schedule and see what reporter turned in the story that ran in the final under the heading Rich Merchant Figures Strangely in Raid on Gay Road House.”

Flynn ran practiced fingers through a sheaf of scribbled sheets. Then, “Overton wrote that story, Mr. Crisp,” he answered.

“Overton, eh?” Mr. Crisp’s accent was ominous. “Boy, tell Mr. Overton to come here.”

The boy vanished behind a rack of lockers at the opposite side of the big room. Immediately from some recess back of the lockers there appeared a small shabby man with white hair and a bleak, pale face. He was in his shirt sleeves. He wore a frayed collar of an old-fashioned cut, a little rusty black tie and on his lower arms calico sleeve protectors. His stubby fingers were stained with ink marks. Everything about him — his pigeon-toed, embarrassed step as he approached his superior, his uneasy light blue eye, the fumbling hand that he lifted to a stubby white mustache — seemed to advertise that here was a typical example of the well-meaning but unsuccessful underling. He offered a striking contrast to the smart appearing younger men scattered about the city room, who raised their heads from what they were doing to follow him with their eyes as he crossed the floor.

“You wanted me, Mr. Crisp?” said he, halting on the farther side of the city editor’s desk.

“Yes, I wanted you.” Mr. Crisp’s voice was grim, with an undertone of menace in it. He shoved the clipping in his hand almost into Overton’s face. “You wrote this — this thing?”

“Yes, sir, I wrote it, but — “

“Never mind the buts. Never mind offering any explanations or any excuses. You admit you wrote it — that’s sufficient. Well then, do you know what you’ve done? You’ve done this gentleman here a great injustice — he’s convinced me of it. You’ve injured one of the most prominent and respected citizens in this whole city. You’ve made his family unhappy. And in injuring him you’ve injured the Beam. Well then, you know the rule on this paper about this sort of thing.”

“Yes, but Mr. Crisp,” pleaded the stricken offender, “you know how hard I try to be careful about details. You know I’ve never made a slip before. And I thought I got my information from reliable sources.”

“You thought? What business had you thinking? How often have you heard me say that the Beam wants proof behind every statement it prints — cold, hard proof; not what somebody thinks. Overton, you’re done here. I’m sorry for you — but as I said just now you know the rule about carelessness. You can’t stay in this shop another hour. Here” — he scribbled a line on a scrap of paper — “hand this to the cashier on your way out. It’s an order for what salary is coming to you. And now please get your hat and coat and leave here and don’t you ever come back.”

There was final judgment in the way he said it. He had been judge, jury and accuser before; now his mien was that of the executioner performing a disagreeable but necessary task conscientiously — and relentlessly. The condemned one bowed his abashed head as though realizing the futility of any appeal, any plea in extenuation or any plea for pardon. Without another word he turned away, a pitiable shrunken little figure of failure and regret and humiliation, and went back to the corner whence he had emerged. Half a minute later, with his hat on his head and his coat on his back, he reappeared and with his eyes fixed on the floor in front of him passed out solitary and aloof in his disgrace.

Mr. Crisp turned to Mr. Gillespie.

“Well, sir,” he said, “that job is done — and to your satisfaction, too, I trust.”

Mr. Gillespie was a kindly enough man. In his own business he was not given to maintaining discipline so mercilessly as this. The thing he had just seen gave him almost a guilty feeling. In a sudden rush of compassion he forgot the principal object that had brought him hither.

“I’ve got to go — just remember an important engagement,” he said. “I’ll probably be back later in the day.”

And out he hurried to overtake this man Overton — or whatever the little fellow’s name might be. He caught up with him at the elevator. Together in an awkward little silence they descended to the street floor.

“Say, listen here,” blurted out Mr. Gillespie when they had stepped out of the car — “say now, that was pretty rough on you. I realize that you didn’t know me — that you had no malicious desire to hurt me in what you wrote — that you merely got the thing twisted round the wrong way. Really I suppose it’s the sort of thing that might happen any time. Newspapers have to fill up their columns somehow. I’m sorry about this — really I am. Don’t you suppose that if you waited here and I went back and had another talk with your city editor and told him that I wished he’d take you back that maybe — well, damn it, man, I’m supposed to be the aggrieved party to this transaction anyhow and he ought to listen to me if I put in a word for you!”

The discharged man shook his head.

“I’m much obliged to you, sir,” he answered miserably, “and I’m sure it’s very kind of you to volunteer to help me, especially under the circumstances, but really, sir, it’s no use. I’ve broken the strictest rule in this whole place and I’ve got to take the consequences. One slip-up, and out a man goes. It was just my luck that it happened to be me. No, sir, I’ll take my medicine and get out.”

“But say now,” pressed Mr. Gillespie, “you’re not exactly a young man. It might be sort of hard for you to get another job. If you should need help now to sort of tide you over while you’re looking round for something else to do — “

“Thank you for that too, sir,” said Overton. “But please don’t concern yourself about me. I’ll get along, I guess — I always have. And I don’t need any help, sir — honestly I don’t. Good day, sir.”

He shambled away toward the rear, heading presumably for the cashier’s department, and Mr. Gillespie, after watching his retreating figure for a moment, passed out into the street, filled with a sense of vague indefinable regret for things in general.

As for Overton, he bided where he had stopped in an elbow of the wall until Mr. Gillespie was safely gone. Then without visiting the cashier’s office he took a walk round the block, came back to the Beam building, rode upstairs to the third floor, silently and unobtrusively reinserted himself into the busy city room, passed behind the locker cabinets to a sort of alcove within hearing but out of sight of the others, and there hung his hat and coat on pegs and sat down at a cluttered desk and went to work as though nothing out of the ordinary had happened.

As a matter of fact, so far as Overton was concerned, nothing out of the ordinary had happened. Being fired by Crisp — publicly and ignominiously fired before all the city room and before irate complainants — was the principal part of his job. He was used to it. It happened to him at least once a fortnight, once a week sometimes, occasionally as often as twice a week. In the organism of The Daily Beam machine he was a humble but a useful cog, for he was the scapegoat, the vicarious sacrifice, the official whipping boy for the sins of others. A whipping boy at fifty — that was what Overton was.

Once upon a time he had been a reporter of indifferent sorts; but that had been so many years before that Overton hated to think back to the time of it. When his legs began to wear out — and his imagination — he had been put on the exchange desk reading papers for reprint stuff; odd times he compiled clippings for the “morgue,” where the published doings and sayings of notables were kept in envelopes filed and indexed, and once in a while he subbed for the frowsy ex-copy reader who under the pen name of Beth Blair wrote the column called Balm to the Lovelorn. When Wendover bought the old and moribund Evening Star and renamed it the Beam and gave it a new and a yellow life Overton came as a legacy from the old ownership along with the hacked and battered office equipment and the green shades on the dangling electric globes and the rest of the fixtures.

It was Crisp who saw in Overton possibilities for the role of scapegoat and developed him in the part. The little man had a sort of cheap histrionic talent. Cast in another mold of environment he might have made a fair actor. Crisp discerned this and worked to bring it out in him — and succeeded amply well. Physically Overton was qualified from the beginning; he looked — well, so hang-doggish. With mighty little prompting he learned to simulate to the very life the guilty aspect of a self-confessed, yet well-intentioned incompetent; and he learned to take his cues from Crisp, as Crisp in turn took his from those indignant persons who came to protest against this or that published thing. So well did he learn that his play-acting very often served a double purpose. Primarily it was designed to give Crisp a chance to prove the seeming determination of the Beam to be strictly accurate and to punish by instant and ignominious dismissal any member of the staff who might unintentionally break the rule. Secondarily Overton’s very mien of sorrowful resignation to his make-believe fate, his dumb and stricken acceptance of dire consequences more often than not so quickened the sympathies of the injured party that the latter — as witness the case of the forgiving Mr. Gillespie — forgot or forewent his original intention of suing the paper for damages.

Considering all things, it might be said that Overton earned his salary, which was thirty dollars a week; just what it had been for long years. He sat at the exchange desk using shears and paste pot and a leaky fountain pen, and on the pay roll was carried as exchange editor, but really, as has been stated, his job was to be fired as frequently as Crisp’s system of office policy dictated that somebody should be fired before witnesses. To Overton it made no difference who had turned in the offending story or who had telephoned it in or who had rewritten it. His task was to assume sponsorship for the slip-up, to be dismissed with harsh words, to get his hat and coat, to leave the office, to walk round the block — and come back again. The city room had its nickname for him. With a sort of half-pitying contempt, it called him The Worm.

He had, no friends in the office, unless Flynn, head of the copy desk, might be called his friend. So far as anyone knew he had no friends outside the office; nor any kith or kin. It was vaguely understood that he lived in a lodging house somewhere up on Third Avenue and that he took his meals in mean restaurants – places where scrap meat masqueraded as Irish stew and chopped-up gristle as Hungarian goulash. If he drank, he drank alone; certainly no one had ever seen him buy a drink for another or accept a drink which another bought. If he had ever had a romance in his life, or a sweetheart or a wife or a child or a tragedy, nobody knew about it and nobody cared. Anyhow he did not look to be the sort of person who would have a romance, but only the sort who would have loneliness and hopelessness for a portion through all the days of this life. From eight in the morning until four in the afternoon he sat at his desk in the alcove behind the lockers, at noontime eating his luncheon out of a paper parcel and emerging only on those occasions when Crisp summoned him forth to play his appointed character. At four he went away; at eight the next morning, he returned; that, so far as the staff of the Beam kenned it, was the sum total of his existence. Once in a great while, when the tides of copy moved slackly, Flynn would invade his refuge to sit for a few minutes on the edge of Overton’s cluttered desk and exchange commonplaces with the little man. It always was commonplaces that they exchanged; never confidences. Even so, Flynn saw more of him than any other man in the shop. He was not a mystery, because to be a mystery a man must rouse the interest or the curiosity of his fellows; must awaken on their part a desire to understand the reasons underlying his aloofness or his isolation, as the case may be. This colorless, solitary creature had not even the elements within him or about him to quicken interest. The office accepted him for what he was — its official scapegoat — and called him by that singularly cruel and singularly appropriate title of The Worm.

As for Crisp, it was characteristic of the man that he never saw in Overton a figure to rouse one’s sympathy or one’s compassion, which is the next of kin to sympathy. It probably never occurred to him that the role he had drilled Overton to play so excellently well was a role calculated to undermine a man’s sense of self-respect. Or if it did occur to him ever he gave the thought no consideration. For Crisp, with all his flair for sensationalism, was a good city editor, which is another way of saying he worshipped the great brazen god Results. He was all for action; subsequent reactions concerned him not a whit. He rarely pressed a reporter to reveal how the reporter had got a difficult story. He was too deeply gratified if only the reporter had got it to inquire regarding the deceit, the evasion, the twisting about of facts or the subterfuge that might have been practiced. This did not imply delicacy on Crisp’s part, nor was it indifference to details. It was in the day’s work, that was all. To him journalistic ends amply justified journalistic means.

Outside the shop Crisp may have been a reasonably human and a reasonably kindly being — probably he was. Inside he was a bloodhound; the picked leader of a trained and greedy pack. Chronicles of misery or misfortune or disgrace were things to be caught at and elaborated and spread-eagled in print. Privately the victims might have his personal condolences; professionally they constituted merely so much good live copy, and as such were to be exploited. Loss of life in a steamship disaster or a tenement-house fire or a railroad wreck was to be desired; the greater the loss of life the bigger the story. After he locked his desk and went away he might have such thought for the dead and the maimed as any average man would have. But before that his solicitude was all aimed at gathering up and weaving into the printed tale every morbid charnel-house detail of horror and suffering which would twist at the heartstrings of the reader and make the reader buy later editions.

Crisp may never have heard of the editor who said he was not too good to print anything which the Almighty permitted to happen, but just the same that was his creed. City editors — some of them–get to be like that; just as reporters, trained to read hidden motives and secret causes under the vanities and the pretensions and the seeming disinterestedness of those with whom in the discharge of their duty they have daily to deal, become in time the most cynical, the most suspicious, the most skeptical of modern breeds. There’s a nigger in every woodpile — find said nigger! That briefly is your average seasoned reporter’s viewpoint of the affairs of life as they relate to the news.

Crisp had another characteristic common among his kind, but in his case developed to a degree which would have made him a marked man any place except in a newspaper shop — the one place where the type is somewhat prevalent. He thought in headlines and he frequently spoke in headlines. Tell him a man’s name and promptly — and mechanically — his fingers began checking off the letters of that man’s name as he counted up and balanced off to see whether the name would fit into the top deck of a headline built of this size type or that size type. For obvious reasons he was drawn instinctively to individuals with short names and instinctively disliked individuals with long names. To him a suicide agreement between two or more persons was a Pact always, just as an official investigation was a Probe and a country-wide search for someone was a Dragnet and an anarchist was a Red and a child of a few years was either a Tiny Tot or a plain Tot, depending upon the caption he mentally set about constructing in the same instant that the subject was mentioned in his hearing. One of the headquarters men would get him on the telephone to report, let us say., that a six-year-old tenement dweller crossing a street had been killed by a trolley car under particularly distressing circumstances.

“Forbes,” he would call out to a rewrite man, “take this story from Doheny, will you? Tiny Tot With Penny Clutched in Chubby Hand Dies ‘Neath Tram Before Mother’s Eyes! Write about six sticks of it.” You see, before ever the tale of the tragedy had been detailed by the outside leg man to the inside desk man Crisp would have framed in his mind a suitable heading.

Similarly, if you stated to him that a young woman defendant was on the witness stand up at the Criminal Courts Building undergoing a searching cross-examination at the hands of the prosecutor, and thanks be to the latter’s persistent proddings making significant admissions, he simultaneously would be translating the intelligence inside his brain to something after this fashion: Accused Girl, on Rack, Bares All. Probably in his sleep he dreamed headlines; certainly he lived with them by day.

This in some share was due to his training. He had been a copy reader before he had become a city editor; but more it was due to the fact that he sucked up and absorbed and made part and parcel of himself whatsoever pertained to the trade he followed. To the job he held, the work he did and the paper he served he gave a wholesouled, single-purposed devotion, which in a more lucrative field than this might have made a rich man of him. The Beam was at once his child and his father. Its twisted ideals, its dubious moralities, its shrieking fakeries, its hysterical crusadings, its frequent service in the public good, its blatant assumption of pure motives, its uncoverings of secret corruptions, its deliberate misrepresentations of causes and individuals, its vain boastings and its actual worthy performances might offer to others a paradoxical mixture of commingled great faults and great virtues, but to old Ben Alibi, sitting there coining imaginary headlines in his head and shaping the news to suit his mood, they were all virtues.

Why not? He had been a main factor in modeling the Beam into what it was, and mortal man rarely quarrels with his own pet creations. In his service to this mudfooted, brass-mouthed idol of his he spared neither himself nor any other. Wherefore it was quite natural that Crisp should take no heed of little Overton’s private feelings touching on the sorry contribution which Overton made to the Beam’s well-being. To Crisp, Overton merely was a cog in the machine and to be treated as a cog.

Accepting such treatment, Overton cogged along, at intervals coming forth from his hiding place like a timorous mouse from behind a wainscoting to be scolded for another’s fault and fired for another’s transgression and then to take his regular walk round the block and return to potter over exchanges while waiting the occasion of his next public appearance. The staff lost count of the number of times its members had witnessed the byplay at Crisp’s desk.

No doubt Overton lost count — if indeed he ever tried to keep one — of the number of times he went through it.

But there is an old saying to the effect that the worm will turn. Probably in the instance of the original worm the turning thereof occasioned all the more surprise among the other worms present because of its very unexpectedness; probably if the truth were known the impulse for revolt had been stirring and stewing in that wormly soul all unsuspected for a long time before it was made manifest in the astounding fact of acrobatism. No doubt it is hard enough to fathom the phenomena of these reactions in worms; and in humans even harder by reason of a human’s superior facilities for concealing the secretly working inner emotions.

As regards Overton, it already has been stated that he had somewhat of the acting instinct, which means the instinct for dissembling. Just precisely when his submerged sense of self-respect, his half-drowned, half-dead manhood began to grow sick of the hateful thing he did to earn his daily bread is past knowing and past guessing at even. It must have been through months, possibly it was through years, that the spirit of rebellion was quickening within him, never by word or deed or look from him betraying itself, yet constantly strengthening and fortifying itself upon the bitter mental food it fed on, against the coming of the hour when the worm, turning, would cease forever thereafter to be a worm and would rise to another plane — a plane as far remote from its former estate and estimation as John Hancock is from Judas Iscariot.

One blistering hot day about midday there came to the Beam office a fluttered young woman with a grievance. Having been brought to Crisp, she stated it. It seemed she was a professional entertainer; she did turns at Sigmund Goldflap’s all night place uptown. Her name — or anyhow the name she gave Crisp — was Lotta Desmond. Two nights before one of the other girls in Sig Goldflap’s troupe had killed herself after a quarrel with one now referred to by this Lotta Desmond as the other girl’s “jump man friend.” And the Beam had printed a picture of Lotta Desmond with the other girl’s name under it, whereat Lotta had suffered deep humiliation. She couldn’t understand why this awful mistake had been made. She’d always liked to read the Beam — it was her favorite evening paper. She had never been mixed up in any scandals herself. She was a lady all over, if she did say it herself. She felt as if she could not hold up her head again. People who knew her, seeing her picture in the paper, would naturally think she was the one who had killed herself. And somethin’ would have to be done right away to put her right with people. Stating her case, she raised her voice shrilly as persons in her walk of life are apt to do under stress of emotion. She repeated the main points of her indictment over and over again, each time using the same words, as might also have been expected of her, considering what — plainly — Lotta Desmond was. Before she was through she was weeping noisily and — one might say — vulgarly.

The city room listened to the vehement outburst, grinning collectively to itself. The city room felt it knew good and well what had happened. It had happened before. To dress up the story of the suicide Crisp had demanded a photograph. Accordingly the reporter assigned to the job had brought in a photograph. There had been difficulties in the way of fulfillment of Crisp’s order, and the reporter had taken a chance — so the city room, harkening, figured the thing out. Possibly the reporter had abstracted a photograph from a grouped presentment of Goldflap’s talent. In such case one might assume he — being naturally hurried — had selected a likeness of the wrong girl. Possibly he had induced a Tenderloin photographer to let him have a photograph, in which event the photographer might have made the mistake with the coincidental result, that a picture of this Lotta Desmond had been bestowed instead of the picture of her dead sister performer. Anyhow the main point with the reporter had been to get a photograph — some photograph, somehow. Dealing with individuals of no social or financial importance the Beam quite often made these little mistakes.

As he sat hearing Lotta Desmond’s indignant recital Crisp had been studying her. It was easy to appraise her. It was easy to assign her her proper niche in the scheme of existence. She had a young body and an old face. You might call her a youthful hag. Her hair was a straw yellow — darker, though, at the roots where the dye had been carelessly laid on. Her frock was a monstrosity of cheap gaudiness. It combined certain of the primary tints — green, blue, brick-dust red; it might have borrowed its color scheme from a map in an atlas. The jewelry she wore would have been worth thousands if it had been genuine. She had about the mentality of a guinea pig — just about. She should be easy — the customary artifice should amply suffice to cajole her out of any idea she might have lurking in that two-cent brain of hers touching on a claim for cash damages for injury to reputation and peace of mind. So he worked the office trick — he questioned Flynn, as per the regular routine, and he sent a boy to summon Overton before him.

Up to a certain point the game of subterfuge was played through as it had been played many a time before. Overton, faithful and letter-perfect in his part of the penitent criminal, took cue from Crisp’s snapped questions and made — or rather began to make — the expected answers. It was not in the book for him to be allowed ever to complete a sentence; he must be caught up sharply with his admissions half framed and incomplete. It was the effect of the confessed delinquent’s demeanor that Crisp desired to produce rather than any definite statements which might be remembered and used afterward in the event of punitive proceedings legally forwarded.

In the midst of the dialogue Overton raised his whitish head and looked full into the face of her for whom the scene had been devised. If he had read compassion for his seeming plight in her shallow pale eyes it was more than any other person there read in them. To the rest she seemed still what she had been from the moment of her appearance — a fit subject for Crisp’s favorite scheme of deception; a young person indignant, yet somewhat pleased at her elevation into prominence before so many strange men; rather embarrassed, and sure before many ticks of time had passed to be suitably placated by the prospect that on her account a man had been discharged from service and sent adrift. It is not probable either that she reminded him of anybody that he had ever known — of anybody, say, that he might have cared for once upon a time. Past doubt what happened was that regardless of contributory causes or the lack of them this hour chanced merely to be the particular hour of Overton’s declaration of independence. It was the hour ordained for his private honor to come forth and walk abroad among men, and since a private honor was a thing which none there had ever credited him with owning, what followed now was all the more unexpected by the audience:

“Stop it, Crisp!” broke in Overton in a voice none there had ever heard him use. “Stop this damn mummery!”

The strangest part was that Crisp did stop — stopped with his eyes goggling in amazement and his lower jaw ajar on a half-finished sentence. He had such a look on his face as a bulldog might have in the event of a sudden counterattack by a bunny rabbit. Overton spoke to the girl.

“Young lady,” he said, “this whole thing was got up and staged to fool you — but it ends right here. I never heard of you before and I never heard of your photograph before and I had nothing to do with the printing of it either. But if I’m any judge of such things — and God knows I should be, considering what I know about this shop — you’ve got a claim for damages against this newspaper and I advise you to get out of here as quickly as you can and go find yourself a lawyer and put your case in his hands. You heard this man fire me just now. Well, he’s fired me fifty times before now, but it didn’t take because it wasn’t meant to. But now it does take, because I’m firing myself here and now.”

He swung back on Crisp.

“Listen!” he ordered, and his words came from him straight and hard like bullets from a machine gun. “They call me The Worm round this shop. And that’s what I have been and that’s what I am — a worm. But you’ve heard, I guess, that a worm will turn, and that’s what I’ve done — I’ve turned. And if you open your mouth to me again I’ll smash you in it — you white livered yellow cur dog!” He set his back to Crisp and the girl and walked away. He nodded a farewell to Flynn as he passed the copy desk, went behind the lockers, came out again with his hat on his head and his coat on his arm; and in the shocked hush which possessed the room he walked out, head erect and shoulders up, for once in his life a figure of force and dignity. The girl followed — a new-formed resolution plainly quickening her to a brisk gait. The city room watched her until her skimpy skirts flipped out the door, then with one accord all present looked toward Crisp.

“The worm turns, eh?” he said casually, half to himself, half to those within hearing. “Well, Flynn, I guess we’ll have to find a likely candidate somewhere for the vacancy that’s just occurred and break him in.”

He checked off sundry letters on the fingers of one hand, repeating the letters aloud as he did so: “W-o-r-m T-u-r-n-s.”

And the city room knew that its chief was translating an experience into a headline — a headline which must go to waste.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now