This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

The Edsel would come to be known as one of the biggest product failures in automotive history. But just weeks before the launch, without the benefit of clairvoyance, a Post editor breathlessly described a cross-country jaunt in the new “mystery” vehicle.

—Originally published August 31, 1957—

The event of this week is the introduction of the first entirely new American motorcar of Big Three parentage in approximately a generation. The newcomer is the Edsel, a well-known if not particularly euphonious family name from the Ford tree. Commercially the Edsel is a competitor for General Motors’ Buick, and it raises the Ford volume lines of cars to four.

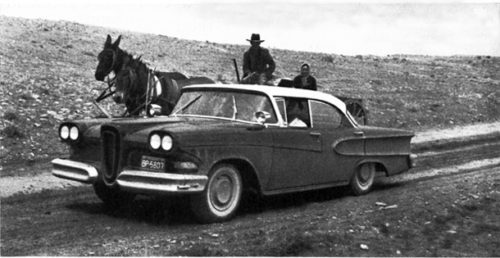

I first met the Edsel in early May a few steps off Oakwood Boulevard in Dearborn, Michigan, behind a protective wall of masonry and security guards. The debutante car was disreputably dressed, for a purpose. As far as was practical, its newness had been concealed or somewhat altered. The car was then officially unborn, although actually three secret years old. We were to go for a spin, furtively and by the worst routes, deep into the Western states. There were three automobiles — a green Edsel, a black Edsel, and a workhorse Ford station wagon carrying engineering equipment, extra Edsel parts, suitcases, coveralls, and potato chips. We made a convoy, two of us in a disguised or blacked-out condition, and we were hooked together by radio-telephone and a comradeship of semi-secrecy.

Although the basic engineering of the new car had been thoroughly honed on guarded proving grounds, it was still necessary to subject the nearly finished product to the experience of assorted public highways on the plains, over the mountains, and through the deserts. The trip had to be somewhat sneaky. We had to avoid too-close and too-frequent public inspection. We dared not offer anyone a chance to take pictures which might be published prematurely or delivered to competitive manufacturers, thus making an anticlimax of this week’s debut.

Such concealment is normal in road trials of annual models by every member of Detroit’s cloak-and-dagger auto industry. For a brand-new line of automobiles it is twice as important. And yet there is a delicate limit to the camouflage. A blackout complete enough to breed no talk, rumors, or anticipation would be painful. A new car, ideally, should be heard about but not seen. It was quite all right for us to pique curiosity, wrong to satisfy it.

Our Edsels were part handmade and part production models. They wore black adhesive tape over chrome trim or had the trim removed. Each bore a pair of meaningless metal plates concealing part of the rear contours. Rear taillights were 1951 Ford lights tacked into place.

We risked the road on a Monday morning. In a hazy way, we felt like a bank guard carrying a billion dollars, hoping our position of special privilege might be noticed, but somewhat fearful that it would. Manifestations of interest and curiosity were almost immediate — and uncomplimentary. A passenger beside the driver of a passing car stood up on the seat to gaze at us. He was a boy of about 4. He would have shown more interest in a delivery truck. A dog charged out of a front yard and yelped us along for 50 yards. It was the first Edsel he had ever barked at, and I had the definite feeling he would have barked harder at a 1912 Maxwell.

From then on, the degree of interest in automobiles shown by American citizens began to crystallize. Single drivers were the most persistent inquirers. Most commonly they would pick us up in a town, follow out on the highway, shoot ahead for a front look, and finally give us up, turning back to town.

In Wichita, Kansas, a driver with a knowing grin pulled alongside the green Edsel and started rolling down his window. We pulled back. He pulled back. We jumped ahead. He followed for 20 blocks and through three turns. We put him on our radio: “Fellow in a light green Ford looking us over.”

The lead car asked, “Has he got a camera?”

He did not.

We stopped for gas, for meals, for motels. And then the patterns of interest changed entirely. Now we became familiar with “Hey, Mac ——”; “Hey, you ——” ; “Say ——”; “Hey, mister, what kind of car is that?”

We were allowed only one stock answer. “Experimental car.” Sometimes it was enough, but not often. “Yeah, but what kind of experimental car?”

There was a definite age pattern at our stops. Elderly people could walk or drive past us without a second glance. A fair proportion of middle-aged people could do the same. But teenagers, boy or girl, not yet turned introspective by taxes, sacroiliac, or in-laws, were acutely sensitive to automotive novelties. They displayed a swift homing instinct on service stations. At fuel stops, always at fairly inconspicuous locations, we sometimes escaped questioning by anyone but attendants, who were too polite to push customers too far. But frequently the teenagers appeared within minutes, and by the time we pulled out they had started to cluster, attracting one another like magnets.

They were surprisingly well-informed. It is also true that the Edsels of the convoy were not entirely free of clues. After receiving our stock answer of “experimental car” and realizing that no further information was to be had, they started their own examinations and analyses, too often in inaudible whispers. They observed a suggestion of the Ford family of cars in our roof line. They found the tiny Ford Company mark on some of the window glass. At one overnight stop it was discovered in the morning that a pen knife had been used to lift the tape from a hubcap to reveal the Edsel “E.” Presumably the inquisitors had come from a school group which had caught sight of the cars the previous night. They identified our taillights. More than once a rebuffed teenager would turn to a companion and say, “Those are ’51 Ford taillights. Could be the new Edsel.”

In a residence district of Springfield, Illinois, a fuel stop drew two hot rods and a bicycle into the service station, where our convoy was temporarily revealed by bright lights. A half-dozen teenagers ringed us like wolves around a hurt caribou. “Say, Mac ——” it started again. Then, in the face of our noncommittal answers, the eager beavers began on their own. They spotted the cluster of shift buttons in the center of the steering column, an Edsel innovation. “Hey, look at this!” They correctly tabbed our taillights for a product of Ford. They studied the unchromed, undecorated concentric rings on the radiator, part of the new vertical-front treatment which marks the 1958 Edsel. What they whispered we could not catch, but it was obvious that they were fairly sure of what breed they had here.

Nevertheless it wasn’t enough for them, and we were preparing to pull out. In a final moment of frustration one corn-fed young blond addressed the driver of the green Edsel. “Well, anyway,” he said, “let’s see you spread a patch.” (I was informed that this was teenage language for starting up with such a rush that you leave rubber marks on the pavement.)

At any given moment there are doubtless tens of millions of American cars on the nation’s roads. In this vast circulatory system the odds are millions to one that any fraction of the tiny total of trial cars on the road will meet any other in significant fraction. And yet, on a residence street in a plains town the radio said, “Lead car to middleman and tailgate. Get the two Chryslers in the right-hand lane!” Sure enough, like two small families of rare whooping cranes meeting in the middle of a crow caucus on Cloud Seven, we had fellow sneaks alongside. Pedestrians and other drivers in the block undoubtedly were unaware of the meeting or its improbability. But our engineers knew. The Chryslers had concealed but strange protuberances, and one of them was making an unorthodox engine noise.

They spotted us too. They grinned. “How far west you guys going?” We grinned back. We never saw them again. A young man in a Mercedes Benz set out to examine us, from the front, from the back and alongside. The impish driver of the black Edsel, beating the stranger to the punch, called across, “Hey, what kind of car is that?” Disgusted, our examiner left us.

Ford officials don’t say so directly, but it is pretty obvious that the Edsel is competitively aimed at Buick and De Soto, which means it will, at the extremes of its range, compete with several other cars, including a couple of Ford’s own products. It will be sold by about 1,200 exclusive dealers. The customers of these dealers will ultimately declare what its niche shall be. At any rate, this week’s debut will clarify things for a freckled young man who viewed the convoy cars at a Midwestern fuel stop. Rather than risk a serious identification which might later prove wrong, he addressed a companion with pseudo self-confidence. “It’s a light bomber,” he said, “but I can’t see how they’re going to get it off the ground.”

—“I Rode Detroit’s Mystery Car,” August 31, 1957

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

An interesting look at the near last minute ‘real world’ rigors the Edsel could be subjected to, while still trying to retain its mystery in early May ’57. A month later when I was 2 weeks old, part of the forthcoming mystery car’s fender was revealed on the cover of Newsweek.

The excitement pretty well died down when the car was introduced. Ford wanted to beat GM at its own game, or at least have a car-for-car choice from Ford for their Buick and Oldsmobile. It didn’t work. Not in its attempt at market segmentation penetration, or really anything else.

If any year it could have had had a chance to do damage to Buick, it was 1958. The Buick looked terrible and sold the same way. The bad economy that year didn’t help, and Buick was given the first of the Jetson-like ’59s weeks before any other GM divisions were given their new models.

Regardless of their ’58 blunder, Buick had a long history of high quality, beautiful cars. Edsel, an upstart, went out the gate with a peculiar front and back end, strange siding, an odd pricing strategy not only with GM, but with Ford and Mercury. On top of THAT, there were build quality problems—from the beginning.

The sizzle had had the flames up too high, promising too much, while the steak itself was an uncooked, unnecessary, third misfit version of a car Ford and Mercury already had under control categorically with GM.

Robert McNamara, President of Ford at the time (and always opposed to the Edsel) knew right away he had a lemon AND a crisis on his hands. For ’59 he drastically cut the number of available models, and greatly improved the front end (see bottom illustration) while still retaining the theme. He also made the car essentially a ’59 Ford (saving $$) with outer styling distinctions differentiating them.

The all-new ’60 Fords provided the also all-new (Ford-based) ’60 Edsel with almost a fresh start. It even had a variation of the ’59 Pontiac split grill up front. Ironically Pontiac went with the ‘shark’ grill for ’60. The Edsel never made it into ’60 itself, with the plug pulled that November.

The Edsel was the wrong car at the wrong time. Well, any time would have been wrong. What WAS needed was the car we’d know later as the the Comet, then Mercury Comet (with the Ford Falcon of course) filling the compact void only Rambler had to that point.

Robert McNamara successfully distanced himself from the Edsel fiasco with one of Ford’s greatest triumphs in early ’58 with the introduction of the 4-seater Thunderbird. A smash hit from day one, it created the personal luxury car market that would later be followed by Grand Prix, Riviera, Toronado, Monte Carlo, Cordoba, Buick Regal and more. It also helped as a needed Edsel distraction for Ford exactly when it was desperately needed.

McNamara had the 4-seat ’58 T-Bird in mind as the first of the two-seater ’55 T-birds were coming off of the assembly line. He had great success at Ford. What happened during his time as Secretary of Defense in the Kennedy-Johnson years though is another matter for another time.