Beginning of the end, is what I thought. One bum step put me out for a week. Mostly I was confined to the decking in front of my tent on the edge of camp, leg up, ice pack on my ankle.

My three Batswana guys came out for their instructions when they felt like it. The English girls, Pippa and Ellie, visited occasionally, fussing. Leaving hours with myself, worried about being, now, in sight of 50, and what that means when your job is essentially physical. Then the elephant turned up, and there were two of us contemplating mortality.

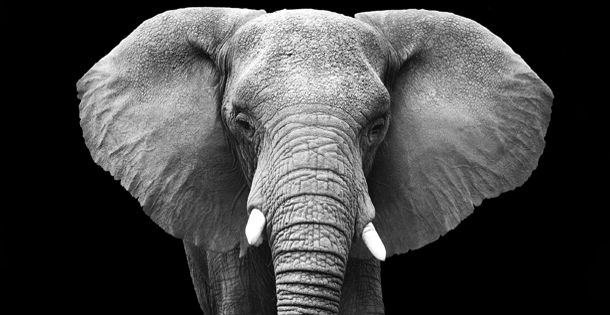

He was alongside without preamble. How he got through the mopane woodland without snap or crunch, I don’t know. Elephants are not stealthy by nature. I lifted my eyes and there he was, more topography than animal: a vertical landscape of ridges and fissures, crusted with sand and dirt, patched with thickets of wiry hair.

First thing you’re supposed to do if an elephant appears without warning is stay stock-still. My enforced immobility took care of the dissident impulse to run like blerrie hell. In the immediate moment, my breathing stopped. I brought it back online, keeping the breaths long and shallow.

My crutches were flat to the decking. I reached a slow hand to gauge the gap, coming up short by some centimeters. Opportunism was not a getaway option. So long as the elephant stayed where he was, side-on, head behind the tent, there was no immediate danger. No sooner had I made that assessment, he began to reverse.

The heavy skin sagging from the peak and hollow of his pelvis pulled taut as one stump foot lifted and reached back, then the other. A ragged ear came into view, the big, veined sheet of it pinned down with black studs. When the ear flapped, those studs burst into an eddy of flies. They fixed again when the ear flapped back.

The elephant halted full profile. An amber eye glimmered behind a thick brush of eyelashes. He stood there for an age, though in real time no more than five, six minutes. When he shifted again, I was hopeful he would leave me to my boredom. No such luck. His rear end rotated, tamping down saplings and bushes, until we were face to face. More than that. His trunk snaked my way, and we were nose to nose.

With snuffles of stagnant air, the prehensile tip explored my nose and brow, tip-tapped up across my forehead, pinched through my hair. I took it as a gathering of information; he didn’t quite know what he had in front of him. When the trunk drew away, I was of the presumption that he was blind, or near enough.

Deaf as well, maybe. I tested it. “Hey, guy,” I spoke. He was impassive. “Hey!” I repeated several times, dialing up to the verge of shouting. Finally his ears twitched. The flies scattered, then coalesced. “Hey,” I said again, reducing the volume a touch. His ears responded; the flies likewise.

If he intended malice he would have threatened it by now. I was confident enough of that to divert my attention to rearranging my predicament. I took the mostly melted ice pack off my ankle and eased that leg to the deck, wincing at the electric jolt when my swollen foot touched the slats. I bent forward to snag the crutches, slid them round, lifted them up, clamped them vertical between my knees. I checked the elephant’s reaction.

He had stayed as he was, head-on and inert. Now I was able to take a good look at him and saw just how old this guy was. His tusks were thick, not especially long. That’s typical for the Okavango. The ivory here doesn’t measure up to other parts of Africa. Some of the researchers would give you an explanation, but don’t ask me on that kind of science. Camp maintenance is my limit.

His declined senses and the jut of his pelvis were giveaways of his age. His scooped-out temples, deeply cast with shadow, compounded the evidence. Now as I said, I’m no expert, but I’ve seen plenty of elephants in my time, and I estimated that this guy was north of 60 at least. Maybe past 70 even. In a place like the Okavango Delta, with its floods and droughts and bushfires, that’s some achievement.

“Hey, man,” I said, intuitively modulating my voice to be heard without causing alarm. “What brings you here?”

He transferred weight between his front legs. There was weariness in the movement, and also intransigence. He’d touched and sniffed my face, he’d heard my voice, and he was going nowhere.

At my age, there’s only so long you can wait out a situation before your bladder has its say. I climbed the crutches and hooked my arms over them, then shuffled the long way round my chair to the tent, watching him all the while. I’d left the flap half-fastened. I unzipped the remainder and went in, through to the bathroom out back. I relieved my discomfort and flushed.

Rational thinking would have kept me in the tent. I could continue my convalescence as easy inside as out. Hell, man, my tent’s stocked with a few books, a Walkman and some tapes, and a cool box of Castles. It would be no great inconvenience. But there was something about that old guy. A recognition, you could say. A common ground. A solidarity. I couldn’t just leave him there. So I pegged back out, turned the chair slightly toward him, moved the table on which I’d left a couple of books, and binocs, and a bottle of water, and brought the other chair round to rest my leg on. Reorganized, I sat back down.

This was us for the next three days. I took regular toilet breaks. The elephant just went where he was standing, never more than a strained trickle. Three times a day I crutched my way over to the dining hut for meals. The elephant had no apparent appetite or thirst. Nights I slept inside with the zip down tight, not against him, but in mind of the usual nocturnal threats of the bundu. If anything, I slept better for knowing I had a sentry outside.

First afternoon, Ellie came out to check on me, totally unaware I had company. I cut short her shouted greeting with a palm held up rigid, then a finger to my mouth. I waved her across to me. She’s been in the Okavango 18 months now and studies lions for her day job, so it takes more than a bull elephant to scare her off.

She came in close, crouching beside me with her hand partly on the cuff of my shorts, partly on the skin of my thigh. For a time I was more conscious of that than of the elephant. Was it just an innocent sign she was at ease with me, now that we had known each other as colleagues for a few weeks? Or something more?

“How long’s he been here?” she whispered.

“Couple hours,” I whispered into her close ear. She smelled fresh and scented, like a shower.

“Goodness me, he’s getting on a bit. How old do you think?”

I told her my upper-end estimate. Over 70. She nodded in acceptance. On some matters of opinion, the researchers seem to regard me as a peer. Hell, I’m no kind of zoologist, and there’s plenty I don’t know. But you put a man in the bush most of his life, he picks up a thing or two. I know wild animals better than I know people. Often prefer them, too. There’s no subterfuge. If you can read the signs, it’s all in plain view.

We whispered to and fro a few times more, and I inhaled my fill. At last Ellie said she had to get back; she was heading out with Pippa to track the Burbank pride. They’d been putting in good work with those lions these past weeks. Those two girls, fearless, man. I’ve seen them sitting on the roof of their Land Rover, not a care in the world, with the lions all round them. Like I say, if you can read the signs.

Ellie lifted her hand away to stand up. Its pressure lingered long after she’d retraced the path through camp to the office hut.

Second day the elephant was still beside the decking, same position, same demeanor. After breakfast, I arranged myself in situ and started thinking about that sense of solidarity I’d felt the previous day.

The two of us were not so different, clinging to our memories of how things used to be. I guessed he’d come to this patch of mopane woodland because it meant something to him. He would have known it long before the research camp was here, with its line of tents, and the office and dining huts, and the generator chugging out noise and fumes, and the comings and goings of people and vehicles.

In his lifetime, the entire Okavango had been transformed, not just this wooded island between the channels. The southern part of the delta has been carved into concessions for tourist lodges and research camps. The elephant’s luckiest stroke was living away from the old hunting concessions up north. You won’t find many old bulls there, if any.

Did he wonder where the tribal villages had gone? Did he mind the whole place becoming crisscrossed with sandy roads? Was he irritated by the Cessnas droning overhead between airstrips, and the motorboats whining along the channels? Did he tolerate vehicles stopping beside him with camera lenses glinting and autofocuses beeping, or was he one of those bulls who’d send them into reverse-gear retreat with a show of bluster?

His past is here. Mine is South Africa, where everything also is beyond recognition. My home street in Joburg, in Bellevue East … hell, man. Every family I knew way back when is gone. I can’t go there and be safe. You can lay on all the political reasons you like, and sure, they’d be justified, but I can’t help but take it personal when nobody gives a damn about how I’ve lost my place in the world. I’m left drifting here and there for jobs, and my fitness for heavy-duty maintenance is fast running out. After that, then what?

Third day, the elephant died. I saw it coming for an hour or two. When I came back from breakfast he had moved round to the front of the decking. Both ears had wilted, giving a different shape to his head. The flies now were crusted around his eyes and in the lip of his trunk.

My ankle was restored enough for me to be able to walk with a stick. I hobbled across to him and, cautiously, from my elevated position on the slats, placed my palm on the broad part of his trunk between his tusks. His eyes closed. We stayed joined for some time.

Ellie and Pippa came to see how he was and rested their hands on my shoulders while I rested my hand on the elephant. The girls stayed with me as the indications became ominous. The elephant began to sway. We could hear the rattle of his lungs, transmitted short through his mouth and long through his trunk. He moved into a clumsy turn, rotating to the view that had been my first sight. His profile was diminished now. Whether he was still conscious, we couldn’t tell. Finally, with terminal inevitability, he keeled away from us, breaking into the undergrowth like a felled tree. The disturbance settled to indifferent stillness.

We went down to him. His eye opened in acknowledgment. We swept away the bothering flies, and we stroked his thick, bristly hide. When the eye sank into its socket, we knew he’d gone. We maintained our vigil for a few more minutes, affording him some final dignity.

It all changed when Ellie radioed the news to the office, one hand on Pippa’s arm while she made the call. There was as much in that touch as the one to my thigh. Camaraderie, you could call it. The girls are half my age, and some. Their fondness for me is the same they’d have for a grizzled old lion. Or this elephant.

We knew he couldn’t be left. The carcass would soon attract hyenas, crocs up from the channel, maybe lions even. Not to mention the stench. Aussie male and female — the chief researchers, our bosses — drafted in a tractor from the tourist lodge. Noosed around the neck by chain, the elephant was unceremoniously dragged through the thick bush in front of my tent to the edge of the water, then across mud and reeds to a clearing a couple of klicks from camp.

The lodge’s return for their help was the elephant’s skull, which would be left out for weeks to be picked clean, then installed in front of reception as a feature. The tusks were chainsawed out by Parks and Wildlife for transportation to the government ivory store in Gaborone.

The bush in front of my tent was left flattened to the channel. A cluster of hippos wallowed there. I had heard them often enough; now I could see them. At dusk I steered my chair to gaze out, alone with my thoughts.

There was movement behind me, and a voice. “How are you feeling?”

“Better,” I said reflexively. Then, with consideration: “Haven’t ironed out the limp yet, but I’ll be back to work tomorrow.”

“The elephant, I meant.” Ellie scraped a chair across the boards to settle beside me. “You’re missing him, I’m sure.”

“Ag.” I reached to the top left pocket of my shirt, where I once kept a pack of Marlboros. A good 10 years since I quit. Old habits. I exhaled a lungful of air. Clicked tongue to teeth for final punctuation.

Her hand extended toward me, paused. “I know. I know.” Her fingers hovered short of my forearm. Pulled back.

The decking seemed somehow more spacious than before. Not because of the elephant’s absence or the opening up of the bush. The liberated dimension was vertical, like a roof removed. Whatever had been bearing down on me no longer was.

Stars infiltrated the sky, diluted by the near-full moon as it rose. The usual obligations were sidelined. I didn’t offer Ellie a Castle or anything. No pressure to talk, even. My compulsion to reach for absent cigarettes went away.

The night took the initiative. Hippos, hauling out to graze on the floodplain, chuntered. The creaking-door call of a Pel’s fishing owl above us, two or three trees over. Hyenas chuckled across the firebreak behind camp. The sustained roar and trailing coughs of a lion, out by the airstrip.

At seven, one of my guys would beat the drum to summon us to the dining hut for supper. That would be it. We would return to the fold of daily gossip. Lion news, usually. No doubt tonight overshadowed by the elephant. It being a Thursday, bobotie for main course, with milk tart for dessert. Insects buzzing against the bare lightbulbs overhead, and some of us fingertip-fishing strays out of our drinks. Bundu life has its routines.

But this was new. Ellie beside me, and a view ahead. Beyond the hatchwork of reeds, the liquid moonlight shimmered. Entrancing, luring. Almost obtainable.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I enjoyed reading the short fiction “Tuskers” by Richard Newton. A simple story about a temporarily disabled man forced to engage peacefully with an ailing elephant. I came to care for the elephant and could see the environment all around. Naturally, I was made to feel for the elephant’s demise, which lends to the artistry and depth of the author. Good piece worthy of the printed pages of the SatEvePost. Keep ’em coming!

Though “Tuskers” is fictional, Richard is drawing from years of real-life experience with wildlife. You can find more of his writings (fiction and non-) as well as some beautiful photography at https://irnewtonwrites.wordpress.com/.

Yes, this is a vividly portrayed story — simple yet moving. My mother received her issue of the Post and called me after reading it to tell me about it. She asked me to look into the author’s other works because she’d like to read more stories by him. She’s 93 and was a high school English and literature teacher. I’d like to find out more about Richard Newton for myself as well as her; I’m equally moved by “Tuskers”. Can you help? I’ve googled his name but of course it is not a refined search. I don’t know where to go from here. Thanks for your consideration.

Wow! Just came across this in my email – my husband and I got really touched by the story. If it is truly fiction – the author is amazing. What an incredible picture he has painted and so moving! It does seem as if he really was there. Thank you….