News of the Week: Fall Books, Comma Abuse, and the Weird World of Inebriated Seafood

Read This!

If this were 1988 and a time traveler came back in time and told me that in 2018, Bill Cosby goes to prison, there’s a new Magnum P.I., and President Donald Trump addresses the United Nations, I would have probably put that time traveler in the same category as the guy who stands on the street corner yelling at birds. Of course, it wouldn’t have stopped me from asking him what the Megabucks numbers would be on a certain date.

But those are all actual things that happened this week, which leads me to this: There’s so much news coming at us now, and it’s all simply exhausting. It seems like there is BREAKING NEWS every five minutes (and most of it isn’t even “breaking”), and it has made me tense and irritated. I’m not even on social media and I feel overwhelmed. We’re all in information overload, we all have ADD, and we all need a break.

And we can get that break by turning off the TV, putting down our phones, and opening a book. Here are a few new ones that might interest you.

Leadership in Turbulent Times, by Doris Kearns Goodwin (out now). The historian looks back at four presidents — Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Lyndon B. Johnson — and explains how they became leaders.

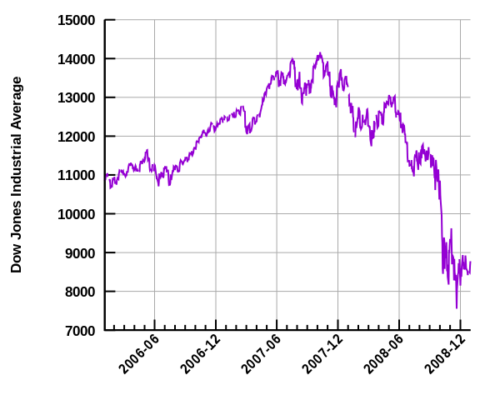

None of My Business, by P.J. O’Rourke (out now). The humorist tries to explain the financial world to us, including why you’re not rich.

Your Duck Is My Duck, by Deborah Eisenberg (out now). The acclaimed author is back with a book of short stories, her first collection since 2006.

My Life with John Steinbeck: The Story of John Steinbeck’s Forgotten Wife, by Gwyn Conger Steinbeck (out now). This memoir by the second wife of the Of Mice and Men author reveals some things that his fans might not want to hear.

Transcription, by Kate Atkinson (out now). The latest novel from the acclaimed author of Life after Life and A God in Ruins is “a dramatic story of WWII espionage, betrayal, and loyalty.” She’s one of Stephen King’s favorite writers.

The Reckoning, by John Grisham (October 23). Grisham’s latest novel concerns an attorney who tries to defend one of the most-liked citizens of a small Mississippi town, who admits to killing a pastor and friend, but won’t say why.

Cook Like a Pro, by Ina Garten (October 23). This is the Barefoot Contessa host’s 11th book. I don’t know if you’ll be able to actually cook like a pro, but I bet you can make something that tastes really great.

Too Many Commas

Never mind foreign policy, the economy, or healthcare. I’m more interested in what the current administration is doing about punctuation.

The State Department is cracking down on the misuse of commas in official documents and press releases. According to CNN, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has sent out emails asking staff to stop using so many commas. It seems that Pompeo is a big fan of the Chicago Manual of Style.

This is all well and good, and I applaud any attempt to fix bad punctuation and bad grammar. I just hope they’re fans of the Oxford Comma.

By the way, the new Magnum P.I. I mentioned above is missing its comma, too. As I told you a while back, CBS did this on purpose so the title would be hashtag-friendly on Twitter and more easily found in Google searches.

Papa John’s May Change Name to Papa Johns

Let me repeat that if you didn’t get it the first time: Papa John’s wants to change its name to Papa Johns.

Do you notice the difference? The apostrophe in John’s is gone (seems like everyone is cracking down on punctuation this week). It’s not a huge change, but the company is trying to distance itself from controversial founder John Schnatter, who is actually trying to buy back the company.

In other name-change news, Weight Watchers is becoming WW. Not only is this name change confusing, it’s also needless. The company wants to focus more on general well-being and health, and not focus so much on weight loss, because the word weight is probably too politically incorrect.

Isn’t WW rather cumbersome? Do they believe that everyone in the world will just forget that the first W stands for weight?

Not to be outdone, Dunkin’ Donuts is changing its name, too. They’re still going to sell donuts (as well as doughnuts), but they want to be known as a beverage place first, so starting in January, it’s just going to be known as Dunkin’. Because everything is ridiculous.

Do We Need a Voice-Controlled Microwave?

No, of course not. But that’s not stopping them from coming.

Amazon wants to be in every single room of our homes, and one of their kitchen items is a microwave that takes commands via Alexa. The Senior Vice President of Amazon Devices says “the user interface is stuck in the ’70s,” and it’s time for something like this. Yes, those days of pressing a button on your microwave are soooooo 1979.

The only way a voice-controlled microwave would make sense is if it goes to the supermarket for me, places the meals in the microwave for me, and then yells at me for buying microwave dinners instead of cooking something myself.

Sea-Weed

Did you know that octopuses (and I’ll never believe that’s the plural) are more social when they’re given the drug ecstasy?

That’s the odd headline in this BBC story. I don’t know why you’d want to make an octopus more social, but there it is.

And they’re not the only citizens of the sea who are getting high. Charlotte’s Legendary Lobster Pound, a restaurant in Maine, has been giving marijuana to lobsters to make them more docile and sleepy before they’re, well, thrown in boiling water. The state of Maine has asked the restaurant to stop doing this.

By the way, Social Octopus was the name of my high school ska band.

RIP Gary Kurtz, Jack Young, and Laurie Mitchell

Gary Kurtz produced such movies as Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, American Graffiti, and The Dark Crystal. He died Sunday at the age of 78.

Jack Young was a stuntman who worked on dozens of movies over the years, including Rio Bravo (he’s the guy who falls from the loft after Dean Martin shoots him), D.O.A., High Noon, The Conqueror, 3:10 to Yuma, The Alamo, and How the West Was Won. He died last month at the age of 91.

Laurie Mitchell played the evil space queen in the 1950s camp classic Queen of Outer Space. She also appeared in Attack of the Puppet People and TV shows like 77 Sunset Strip, Perry Mason, and Richard Diamond, Private Detective. She died last week at the age of 90.

Quote of the Week

“Why would they cancel a popular show that everybody loves?!”

—Kyle, surfing around, looking for his favorite TV show, on tonight’s season premiere of Last Man Standing, now on Fox after being canceled by ABC

This Week in History

60 Minutes Premieres (September 24, 1968)

The venerable CBS news magazine celebrated 50 years this week. Here are five times the show shocked viewers, and here’s our interview with humorist Andy Rooney.

William Faulkner Born (September 25, 1897)

The Post published 22 short stories by the Southern writer from 1930 until 1967. He won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1949.

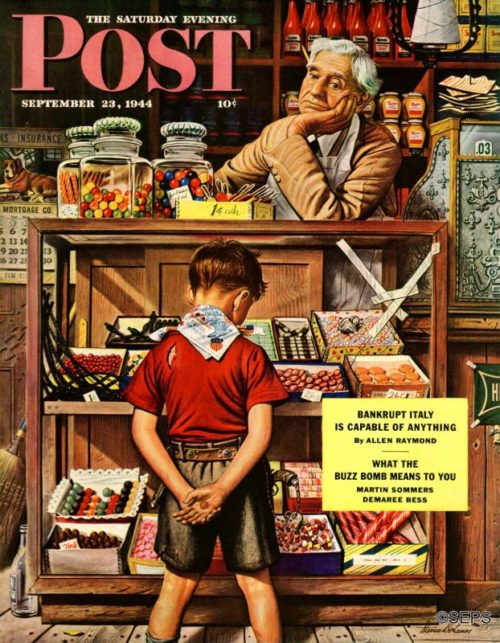

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Penny Candy (September 23, 1944)

Stevan Dohanos

September 23, 1944

One of my favorite childhood memories is going to the store and getting a big bag of penny candy and other goodies. The expression on the clerk’s face in this Stevan Dohanos painting is one I remember well. Come on kid, what do you want, I have things to do.

The taped glass is a nice touch. Probably from kids tapping on the glass too hard, pointing to the candy they want.

National Coffee Day

I always laugh to myself when I hear about this holiday, because people who drink coffee don’t need a special day. They drink it every day anyway. You’re probably drinking a cup right now as you’re reading this.

Saturday is National Coffee Day, and many of the chains are having special deals. I couldn’t find anything for Starbucks, but at Krispy Kreme you can get a free hot or iced coffee of any size. Peet’s is offering a free drip coffee or tea and 25% off a pound of beans at participating locations. And Dunkin’ Donuts is having a “buy one, get one free” promotion on hot coffee all day long.

Oh, sorry: DUNKIN’. I’m never going to get used to that.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Clergy Appreciation Month

October is the month when congregations honor their pastors and priests and their families. This month also has Clergy Appreciation Day, which this year is October 14.

Get Organized Week (October 1-7)

New Year’s Day seems like the logical time to change things up and finally get organized, with a fresh new year starting up. But many people (like me) like to do it in the fall, when the air turns cool and kids are back in school and everyone has more energy and it’s time to go to The Container Store and Staples for supplies to get things organized.

But that’s next week. This week, you can still be disorganized and frantic if you want.

The Best-Selling Author Who Made a Criminal Career of Forgery

“I have a hangover that is a real museum piece; I’m sure then that I must have said something terrible. To save me this kind of exertion in the future, I am thinking of having little letters runoff saying, ‘Can you ever forgive me?

Dorothy.’”

From her pithy poems and short stories to her legendary letters, Dorothy Parker’s snappy and acerbic writing was thought to be unmistakable. But Dorothy Parker didn’t write the excerpt above; Lee Israel did.

The biographer-turned-forger stole or fabricated hundreds of literary letters in the 1990s, and her 2008 memoir, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, has been adapted into a film — starring Melissa McCarthy as Israel — to be released on October 19th.

Before Israel became a criminal of correspondence, she was a freelance culture writer and Times best-selling author. Her biographies of Tallulah Bankhead (Miss Tallulah Bankhead) and Dorothy Kilgallen (Kilgallen) earned her moderate success as an author that was obliterated in a publishing war with Estée Lauder.

Estée Lauder: Beyond the Magic — a gossipy tell-all of the makeup magnate — released concurrently with the businesswoman’s own biography in 1985 and promptly tanked, dragging Israel’s reputation down with it. Years later, she regretted refusing an offer from Lauder to kill the book. As she told it in her memoir, “Instead of taking a great deal of money from a woman rich as Oprah, I published a bad, unimportant book, rushed out in months to beat the other little piggy to market.”

Israel spent years in poverty and on welfare with writer’s block and likely alcoholism. Described as a difficult person, she found it impossible to be employed in wage work, and held resentment for her fall from grace: “Writers, unlike lawyers, doctors, agents, and Verizon Information, do not get paid when they fail or misjudge,” she wrote.

Her crime spree began in the early ’90s, when she lifted some original Fanny Brice letters from the library and sold them for 40 dollars each. One letter, she noticed, bared some white space before the signature where she could insert some juicy lines of her own to up the price.

It was after Israel realized her new medium — forgery — that she created, as she said, her best work. She composed imaginary correspondence from Noël Coward that she claimed was “better Coward than Coward,” and whipped up phony letters from Lillian Hellman, Edna Ferber, and Louise Brooks, among others. One letter authored by Israel, and featured in The Letters of Noël Coward, delivered a course comment on Julie Andrews: “She is a bright, talented actress, and quite attractive since she dealt with her monstrous English overbite.” Israel bragged that her work passed for that of the cosmopolitan creative elite, but it was typed out in “a room with a view not of Alpine splendor, but of brick and pigeons.”

To ensure utmost authenticity in her ruse, Israel scoured secondhand stores for period typewriters — kept in a storage locker on the Upper West Side near her apartment — and she tore vintage paper from old journals in libraries. Her previous writing work had equipped her with the research skills necessary to analyze and imitate the stylistic quirks of larger-than-life entertainers and legends from the Algonquin Round Table. She found autograph dealers around the country who would pay 50 to 100 dollars for each letter, a modest price, and made up stories about how she had come to own them. Many of the dealers, however, were remarkably indifferent about the origins of the works, she claimed.

The truly “evil” part of her new vocation, she admitted, happened slowly. Some suspicions arose when Israel began to write overt homosexual references into her Coward letters (a farfetched conceit, given the harsh offenses for homosexuality in his time), so she stopped drafting new letters and took to stealing the originals from the library. She brought them home, made counterfeit versions, and switched the two. This new method led to her undoing when a dealer came in contact with her library of choice over a Hemingway missive.

Israel never saw jail time, but she did get six months of house arrest and five years of probation for her crimes. In the end, she scantly regretted her years spent in “such good company” as the deceased subjects of her forgeries. Her memoir was named after the ambiguous sign-off she attributed to Dorothy Parker, explaining in an interview, “I want to be forgiven, yet I’m not going to give a full-throated apology.” Israel attributed her actions to desperation and maintained that only someone as well-read and as charming as she could have convincingly brought to life some of the most iconic voices of the 20th century.

The Next Word

The next word to come out of Matthew Vinatieri’s mouth would undoubtedly be the most important one of his life.

This was, to say the very least, an unfortunate turn of events.

Meanwhile, somewhere well outside the confines of Matthew’s lips, the universe was acting predictably uncooperative, as per its usual state of being. Over the loudspeakers, Billy Joel’s voice crooned about Brenda and Eddie who were still going steady in the summer of ’75. The sun was setting. The lights were dimming. The murmur of unrelated lives haphazardly congregated together but for one night grew louder and louder. A bartender poured out another pair of shots for two men in business suits who had been sitting in the same stools since happy hour and who would undoubtedly be there until closing time. Behind them, a group of women celebrated a birthday with shrieks and toasts and glasses of overpriced wine that splished and splashed onto the floor while an older man with sunglasses and a suspiciously runny nose stumbled out of the bathroom door and nearly slipped and fell over a poorly dressed college student who was drinking by himself in the corner with his eyes glued to a hockey game playing on the television screen above the bar, and all the while the dinner crowd continued to shuffle out while the cocktail crowd drunkenly stumbled its way in, and by this point Brenda and Eddie had already gotten an apartment with deep pile carpet and a couple of paintings from Sears. Yet none of the noise and none of the static surrounding Matthew seemed to have the slightest bit of sympathy that the next damn word to come out of his stupid mouth would be the most important one of his damn stupid life.

On the bright side, at least Matthew knew to where he was supposed to direct this said word. That part was easy enough. It was to be directed — at an adequate volume and with a moderate tempo — towards the neighboring stool which stood approximately two feet away from him.

Or, to be slightly more specific, to the man who was sitting on the neighboring stool which stood approximately two feet away from him.

A man named Brandon Kimmel.

Brandon. Twenty-nine years of age with a scruffy beard and blue eyes and a tattoo on his forearm and who was also a good two inches shorter than his dating profile had previously suggested, which Matthew was more than willing to forgive in its totality simply in exchange for Brandon’s unconditional and undying love.

Which, to Matthew, seemed like a fair trade.

And to his credit, the glass of bourbon perspiring on the bar top next to him seemed to agree. Matthew took a nervous sip from it, and another one after that. The bourbon lit a fire on his lips that cascaded to the back of his throat and exploded all the way down to the pit of his stomach. This was already Matthew’s third drink of the night. The first had been a beer he had guzzled frantically while showering, while the second had been a far too strong Irish coffee he had smuggled onto the subway.

The drinks, of course, were intended to serve a very important purpose. They were there to calm Matthew’s nerves, which were in desperate need of calming. Though in defense of his nerves, there weren’t too many first dates for Matthew Vinatieri. Second dates were even rarer. And by this point, Matthew wasn’t quite sure what exactly a third date entailed or if such a thing even actually existed.

Needless to say, it was important for Matthew to get off on the right foot — even if that foot had been rendered slightly inebriated and undeniably uncoordinated. Yet thus far, those three drinks had conspired together to do just the opposite. Rather than making his words silky smooth, the alcohol blended them all up like a cheap cocktail which swished and swirled around Matthew’s head in a jumbled mess. Every little thing made him dumbstruck and confused and in desperate hope that perhaps a fourth drink could get the other three to behave properly.

Every little thing going on was too much. Even little things like simple questions. Which, coincidentally, is exactly what Brandon had asked Matthew.

A simple, little question.

There was no doubt about it, either. There were all the hallmarks of a simple, little question. Small words. Few syllables. Limited variety of letters. All of which formed together into a short and concise question. It even ended in a clear and defined question mark, too. Granted, Brandon had asked this question verbally, so therefore there hadn’t necessarily been a visible, literal, tangible question mark. Per say. But it was still there, all right. Matthew could see it just fine. Brandon’s intonation had been nothing short of a grammatical symphony. It rose in a crescendo, up and up and up before swooping down and then, at the very last second before it crashed into the ground with a fiery flame, it swooped back up again and trailed off into the dimly lit noise of the bar, twirling and twisting in and around itself into a perfectly formed question mark before it all faded away graciously like a puff of smoke whispering something softly into the dead of night.

So, yes. It had been a simple, little question. And at the tail end of that question, there awaited only two answers. Either Matthew could say “yes.” Or he could say “no.”

That was it. Two little words. “Yes” and “no.”

It sounded easy enough. But Matthew knew better. Oh, did he know better. Matthew knew that those two little words were in fact worlds apart. Galaxies, even. And Matthew also knew that whichever answer he picked, whichever word he uttered out of his stupid mouth, it would undoubtedly be the most important one in his life. Deep down, Matthew knew that word would determine whether or not there would be a second date or, dare he even dream, a third date after that. One word and one word alone would decide if Matthew would be led on a path to eternal happiness, or if he’d be forever alone.

“Yes.” Or “no.”

Brenda and Eddie were already starting to fight when the money got tight and Matthew needed to make a decision.

He prodded each word.

First, there was “yes.”

“Yes” seemed nice.

“Yes” was positive, for starters. It was agreeable. It was outgoing and popular and optimistic about the future and it seized the day. “Yes” was the sort of word that looked at the glass as half full. It looked at life with a can-do attitude. And at the end of it all, “yes” led to a plan. Better yet. To a realization that things happen for a reason and that everything works out in the end as long as you believe that they will, gosh darn it.

“Yes” was all smiles and sunshine and kittens. People like “yes.” And more importantly, people like people who say “yes.”

And yet. The more Matthew thought about it, maybe, just maybe, “yes” was a little bit too nice. Maybe it was just a little bit too eager to please.

“Yes” could be simple-minded. Naïve. Stupid. Desperate. And if there was anything Matthew couldn’t afford to come across as, it was simple-minded and naïve and stupid and desperate.

Maybe, just maybe, what Matthew needed was a “no.”

“No” was critical, true. But “no” was also thoughtful. Analytical. “No” was a rebel. Anti-establishment. Black flag. Independent. Punk rock. “No” was a master of its own destiny. “No” didn’t get dictated to by life. On the contrary. “No” grabbed life by the proverbial genitals and told it what the damn plan was. And if life didn’t like it, “no” told it precisely where it could stick it.

“No” was strong.

People like strong.

And yet. “No” could also be a bit of a stick in the mud, too, couldn’t it? “No” could be a bit of a jerk. “No” upsets people. “No” causes waves. And sometimes, people just want to float on calm waters.

Matthew took another sip of his drink.

Time was running out. So was his bourbon.

He grimaced. His face twitched. He hoped that any sort of noise would just hop out of his mouth, all by its own doing. That an answer would find itself.

By now, Brenda and Eddie had had it already by the summer of ’75.

Matthew needed to say something. Anything. And now. So, he weighed both options. He examined their benefits. Inspected their detriments. Made mental tally marks of what they offered and where they fit in and how they could each single-handedly change his life from here on out. And after carefully weighing both options and counting their tallies, he flipped a coin.

It landed with a thud.

“No,” he blurted out. “I mean, not really. No. I don’t really follow any of that stuff. Not really.”

Brandon smiled that smile of his. “Oh, that’s all right,” he said. “You know, I’m actually sort of into astrology myself. I think it’s sort of fun, you know?”

Matthew nodded. The nod was a lie, though. Clearly, he didn’t know. He didn’t know anything. Matthew didn’t know anything for one thing, that is. That this was it. That he had picked incorrectly. And that now, there was no other conclusion to draw other than that he was clearly on a path to eternal loneliness. There would be no second date, he figured, and there would certainly be no third date. Not after an answer like that. No. There would only be more bourbon and Irish coffees smuggled onto the subway and beers drank in the shower.

Well outside the confines of Matthew’s lips, the lights in the bar continued to dim. The dinner crowd dwindled. The cocktail crowd grew larger and larger. Shots were kicked and overpriced alcohol splished and splashed and people stumbled in and out of doors. From a stool approximately two feet away, Brandon smiled that smile of his, a smile which completely escaped Matthew’s notice. And in the background, Billy Joel’s voice crooned about how the best they could do was to pick up the pieces, but that they always knew they’d both find a way to get by.

10 Years Ago: Elon Musk’s Conquest of Space Begins

Space Exploration Technologies Corporation had a vision: they would make it easier to access outer space. Other companies had tried privately funded space travel before, but no one else had attempted it with an ambitious agenda of cheaper builds, reusable craft, and Mars colonization in the long view. But on September 28, 2008, SpaceX took the first giant leap toward their future with the launch of Falcon 1.

SpaceX founder Elon Musk already had a high business profile when he founded the company in 2002. He and his brother had founded the software company Zip2, , with Musk making $22 million off of its sale in 1999. That same year, Musk co-founded X.com, an online financial company. X.com merged with Confinity, and the company renamed itself after the Confinity product PayPal. In 2002, eBay bought PayPal; Musk’s stock share earned him $165 million in the sale. Musk investigated purchasing refurbished rockets from Russia to attempt his “Mars Oasis” plan of putting a greenhouse on the Red Planet, but ultimately realized it would be cheaper to build the rockets himself. With $100 million of his own money, he founded SpaceX in May of 2002.

There had been other attempts to privately fund and launch rockets in the past. The Conestoga, built by Space Services Incorporated, reached space in 1982, but the series was only launched three times before it was shut down. The Northrop Grumman craft Pegasus used an air-launch strategy where it would be lifted into the air by a plane, and then released mid-air for launch. The first successful Pegasus mission happened in 1990; there have been 42 further launches to date, with another scheduled for October, 2018.

But SpaceX always had a longer view, and the differences in approach and goal would be built into the program. Among the SpaceX priorities was a smaller launch price point with an eye toward using the rocket to position low-Earth-orbit satellites; cheaper delivery was seen as a possible boon to business and development and a profit-center for future partnerships. Falcon would also use liquid fuel, which was a departure from solid-rocket boosters used by NASA on the Space Shuttle. The final design for Falcon made it a two-stage rocket, meaning that one stage, after achieving boost and lift, would separate, allowing the main portion to achieve orbit.

It took $90 million dollars to develop Falcon, and that was the small hurdle. The important thing was making sure it worked. The Department of Defense paid for the first two test launches after development because they were interested in seeing what kind of practical application the system might offer. Flight test one failed after one minute because of a fuel line rupture. The second test had multiple issues, but Musk and his team wrote it up as a success because they were able to determine that 95 percent of the systems in the vehicle worked properly. The third launch in August 2008 failed when, after stage separation, two sections of the rocket hit each other again. At that point, things were financially grim for the venture; the next attempt had to be a success.

SpaceX released this video of Falcon 1 highlights.

The fourth flight came on September 28, 2008. As Musk himself would later say, the future of the company was riding on it. One correction — an increase in the time between the burn-out of the first stage and separation of the second — appeared to have fixed the cause of failure from the third flight. Falcon 1 achieved orbit, placed a non-functioning spacecraft weighing 363 pounds in orbit as well, and completed its mission. The Falcon 1 designation would be used again the following year for a successful July 2009 launch that also included delivery of a vehicular payload into orbit. At the 2017 International Aeronautical Conference, Musk was frank about the need for the fourth flight to succeed; he said, “The first three launches failed. . . [The] fourth launch worked, or that would have been it for SpaceX.”

The legacy of Falcon lives on at SpaceX. Falcon 1 was, according to SpaceX, “the first privately-developed liquid-fueled rocket to successfully reach orbit.” Its success secured a contract with NASA to deliver cargo to the International Space Station, with an original cost of a comparatively affordable $9 million per launch. Today, SpaceX has made their way to the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy series; Falcon 9 has had 61 missions, the most recent of which in placed a Telstar 18V communications satellite in orbit earlier this month.

SpaceX hasn’t simply rested on their laurels with Falcon. They’ve continued to push the boundaries of what its possible. They’ve developed the Dragon, a capsule-craft that is capable of carrying either cargo or astronauts; it’s been used in resupply missions for the International Space Station. SpaceX moved sustainability a huge distance forward with their creation of the reusable launch system; this system allows separated boosters to return to Earth under their own power and land for later re-use. The next giant leap for SpaceX will be the BFR, or the Big Falcon Rocket. Scheduled to replace the other series sometime in the 2020s, it will cover all the applications (resupply, human transport, interplanetary movement) and be the most powerful rocket ever created. The BFR would have the capability to satisfy Musk’s dream of Mars; at SXSW in 2013, Musk said, “I’d like to die on Mars, just not on impact.”

While the Mars greenhouse has yet to be conquered, Musk is making good on his vision of cheaper, more frequent spaceflight with reusable components. He currently plans to have a craft orbit the Moon with a civilian on board as part of a “lunar tourism” initiative. During the commission of Falcon development, Musk also had time to found auto manufacturer Tesla in 2003. Whatever direction SpaceX goes in the future, it’s sure to be eagerly observed and imitated.

Unfortunately, the anniversary of Falcon’s success finds Tesla in serious turmoil. On September 27, the Securities and Exchange Commission accused Musk of making false public statements based on a comment that he made on Twitter in early August. According to the SEC, Musk’s tweet, “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured,” constitutes a type of fraud that could mislead investors. Tesla’s directors released a statement that the are “fully confident in Elon, his integrity and his leadership of the company.” Tesla itself is not named as a party in the suit. It will likely take some time for this situation to play out in the courts. No matter the outcome, one thing is certain: Elon Musk has a knack for getting attention.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

In a Word: An Airing Out of ‘Feisty’

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The adjective feisty is often used to describe people (usually women) who show a lively aggressiveness in their demeanor, like one of those small, yappy dogs that seems to have endless energy and spunk. The comparison here isn’t an accident: feist has been a generic term for a small dog used for hunting game animals since the time of the American Revolution, and later it became a derisive term for a lapdog, both literal and metaphorical.

Feist came from the shortening of an earlier phrase fysting curre, “stinking cur.” We might think of a cur, if we think of it at all, as a low-bred or immoral man, but the term was originally a deprecatory term for a dog.

The fysting (or fisting) of fysting curre comes from the Middle English verb fysten (or fisten) “to break wind,” which is also where we get the word fizzle.

Etymologically, then, feisty traces back to the expulsion of malodorous intestinal gases.

While we often hold Shakespeare up as a matchless master of English composition, he was no stranger to either the common vernacular or bathroom humor. Thus we find, in Pericles, Prince of Tyre Act IV, Scene 5, the following outburst from Pericles’ daughter Marina:

To the choleric fisting of every rogue

Thy ear is liable, thy food is such

As hath been belch’d on by infected lungs.

Language changes, of course, and while we do find arguments to avoid feisty because of its sexist overtones, at least it’s divorced from its flatulent past.

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The Story of Uncle Sam

Who is Uncle Sam? Why is he dressed that way? And how did he come to represent the United States?

See more History Minute videos.

Top 10 Reads for Autumn 2018

Every month, Amazon staffers sift through hundreds of new books searching for gems. Here’s what Amazon editor Chris Schluep chose especially for Post readers.

Fiction

Transcription

by Kate Akinson

A young woman’s past life in British espionage during WWII unexpectedly revisits her 10 years later.

Little, Brown & Co.

Virgil Wander

by Leif Enger

A small Midwestern town blossoms to life through Enger’s depiction of its colorful denizens.

Grove Press

The Witch Elm

The Witch Elm

by Tana French

Toby leads a happy, unconcerned life — until a skull is found in a tree, leading us to question what lurks beneath the surface.

Viking

Unsheltered

Unsheltered

by Barbara Kingsolver

In alternating chapters, this novel tells the story of two people separated by a century and what it takes to face life’s challenges.

Harper

Washington Black

Washington Black

by Esi Edugyan

Profound, beautiful, and wise, this book about a runaway slave is also a full-blown adventure novel that is full of twists and turns.

Knopf

Nonfiction

21 Lessons for the 21st Century

21 Lessons for the 21st Century

by Yuval Noah Harari

The Sapiens and Homo Deus author provides 21 essays to help you untangle and prepare for the near future.

Spiegel & Grau

The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers

The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers

by Maxwell King

The iconic Mr. Rogers finally gets the full-length and definitive biography he deserves.

Abrams Press

These Truths: A History of the United States

These Truths: A History of the United States

by Jill Lepore

The first single-volume history of America in decades, written by a New Yorker journalist and Harvard historian.

W.W. Norton

Leadership in Turbulent Times

Leadership in Turbulent Times

by Doris Kearns Goodwin

The celebrated biographer draws upon four presidents — Lincoln, the Roosevelts, and LBJ — to examine what it takes to lead.

Simon & Schuster

Napoleon: A Life

Napoleon: A Life

by Adam Zamoyski

Zamoyski’s examines what Napoleon was trying to achieve, in the context of the European Enlightenment.

Basic Books

North Country Girl: Chapter 71 — Me and the Other Guy

Gay Haubner is taking a hiatus from her weekly series. Look for occasional updates in the future. For more about Gay’s life, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

1980 was the winter of my discontent. I had a dream of a life in Manhattan, barely working at Penthouse magazine, enjoying my own expense account plus our advertisers’ largesse, and going home at night to Michael, my artist boyfriend, to party in our own tiny apartment, or out at bars and clubs with a slew of musician, artist, and writer friends. But inside me there was a gnawing worm, a niggling “What if?” that had taken root when I turned down an offer to join the crew of a Mediterranean yacht as cook and bottle washer.

Where in the world would I be if I had dared to accept that job? What adventures, what interesting men had I missed out on? Who would that girl be if she had walked the gangplank onto the yacht with nothing but her passport and a handful of pesos, leaving her New York City life behind? I rode the subway to work, turned in my magazine copy, kissed Michael good night, and rued that sensible decision to stay in my enviable rut.

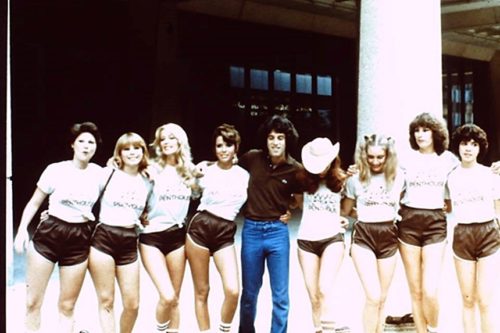

I was a latent dumpster fire in need of a thrown match. The spark that blazed my life to the ground was lit at a party at the apartment of the Penthouse production manager, in the midst of a mass of people who had collectively reached that level of inebriation where everyone is dancing. Rockpile’s “Girls Talk” was blasting at a volume of 11 and I was swirling in the arms and trampling on the feet of a wiry, bushy-haired, Brooklyn-tinged guy from work, one of those cute Canarsie kids who can pass for Italian.

I wasn’t sure what Jeff’s real job was; I knew him as the coach of our Penthouse Pet softball team, which had recruited me to pose as a fake Pet, barnstorming across New Jersey and Long Island. I played left field like Ferdinand the Bull, smelling the flowers while ground balls and popped flies passed me by. It didn’t matter. These were charity games against the Elks and VFW and Rotary Club, teams made up of civic-minded suburban dads, good clean Penthouse fun for good causes.

My softball coach’s hands wriggled down to find my ass, a move that might have been cause for a lawsuit 30 years later. We were both out of our minds, bordering on blackout unconscious, but I felt lips and hot breath on my ear and heard words that singed me: “I could really go for you Gay…if I didn’t like your boyfriend so much.”

It felt like another door closing, another option cut off…because I had a boyfriend.

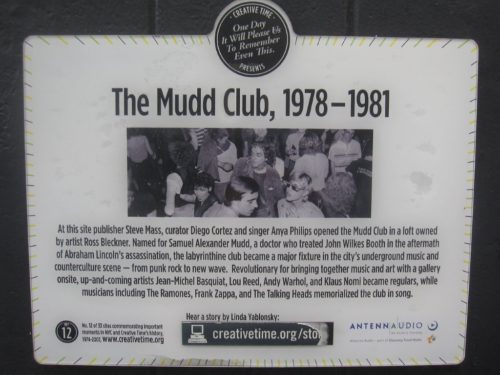

The next weekend I rounded up a bunch of my Penthouse pals for a night out at the infamous, ridiculously popular Mudd Club. The Mudd Club was the last hurrah of NYC punk culture; it had its own obliging PR agent. “I’m calling from Penthouse magazine, we’re interested in doing an article on the Mudd Club,” I had fibbed on the phone. The PR guy assured me my name would be at the door and asked how many. “Oh, there’ll be a few other people from editorial,” I said.

We showed up at the Mudd Club at midnight: me, my boyfriend Michael, six people, not necessarily editors, from Penthouse, their dates, my softball coach and dance partner, Jeff, and random friends we had picked up earlier. I wormed my way through the crush of punk hopefuls to the Bluto in charge of admittance, who, mirabile dictu, found my name on the guest list. I waved to my friends, shouted, “Come on!” and was swept inside on a wave of shoving, thrusting bodies.

The door slammed shut behind me. It was as dark as a mine and I was at the center of a throbbing mob, unable to see if everyone had gotten in with me. The whole place was a filthy mosh pit, floors so sticky you could barely move your feet, everything, even the ceiling, painted black and covered with graffiti, ear-shattering music that made conversation a ludicrous idea, an atmosphere tinged with piss and sweat and spilt beer.

A strong hand grasped my arm and pulled me over to the wall. Jeff handed me a Rolling Rock and a Quaalude, never my favorite drug but an old pal from Mexico. I took them both. “Who else got in?” I yelled, and Jeff shrugged.

Then we leaned back against that grimy brick wall and we were kissing and hands were maneuvered inside clothing and Jeff and I were doing everything outside of actual sex, which at the moment seemed like the most appropriate thing one could do at the Mudd Club, like snorting coke at Studio 54.

The hour we spent in fervent frottage wasn’t enough. “What time do you have to be at work Monday?” I asked when Jeff let me up for air. He looked puzzled; were we going to do this for the next 36 hours?

“Ten?” he answered.

“I’ll be at your place at nine,” I said, extracted myself, and found my way outside, almost certain in my addled state that my boyfriend Michael would still be hanging around. He was at home, rightfully furious, and drinking straight from a bottle of Jack Daniels. I was tousled and plastered myself as I apologized and told untruths about how I had searched the Mudd Club for him, certain that he had been right behind me, and then couldn’t find a taxi.

The actual, real, illicitly thrilling sex happened Monday morning; then Jeff and I split a cab from his apartment uptown to the Penthouse office. We rode in silence. That was fun, I thought, it’s good to get it out of my system, once was certainly enough.

Once was not enough. I did not escape from my perfect life on a yacht or a plane, and certainly not on a train to glory. I climbed into a handbasket to hell. I plunged into a dirty affair, heated even hotter by our struggle to find somewhere to do it: Jeff’s roommate regarded Michael as his good friend, as did everyone I had ever introduced to Michael.

I imagined our affair as a stain on a shirt, I just had to keep putting it in the washer until the stain was gone and the shirt was wearable again. But there was no out for this damn spot.

As all successful cheaters do, I became an accomplished liar, especially to myself. But now I can see the awful truth. It was fun. It was a champagne fizz of feelings, a flip-flopping stomach, skin ready to burst into flame at a touch. Even my eyesight sharpened; it was like getting my childhood once-a-year glasses upgrade, the world in high-res.

And my hearing was dog-pitched; every bar and restaurant I went to, every car radio that passed was tuned to the Miscreants station: “Me and Mrs. Jones,” “Dark End of the Street,” and “If Loving You is Wrong” on repeat all over New York City.

Michael didn’t seem to notice that I was being invited to more nighttime press events, even when those events morphed into weekend affairs.

My job had always provided me access to test drive cars, a perk I had never taken advantage of, Michael being completely disinclined to leave the city for the wilds of upstate New York or Connecticut lest he be lost in the woods, eaten by a bear, or more than a block from a bar.

Jeff and I took stolen weekends in borrowed Datsuns and Subarus, headed for the homes of friends of his who had never met Michael, so Jeff could pass me off as his girlfriend.

A Sunday night, we headed back from Providence, Rhode Island, ostensibly visiting one of Jeff’s high school pals, but spending most of the weekend in the friend’s basement guest room. We were on an almost deserted highway that stretched ahead of us in the dark, a long way to New York City, a long time for me to ponder my sins.

I have to do something, I scolded myself. I love Michael, I can’t go on like this. Meanwhile the part of me that wasn’t lying knew I certainly could until something made me stop.

The single car in front of us accelerated and began to swerve from one lane to the next. I had been so quiet for so long that I couldn’t find my voice to cry “Watch out!” not that Jeff had a clue where to steer to not be in the path of this lunatic, who now sped across all four highway lanes and side-swiped a sixty-foot floodlight. In what seemed to be slow motion, the streetlight pitched towards our car like a felled redwood, hit ten feet in front of us, took a bounce, and landed inches in front of our loaner, a factory-fresh Nissan 280ZX. The flashing lights of the highway patrol appeared in the northbound lane, coming for the guilty parties; Jeff inched our borrowed car onto the shoulder and around our brush with a well-deserved death.

A believer in signs and portents, I almost saw the light. “We can’t do this anymore,” I said to Jeff after we dropped off the car at the dealership, even while we were in a clutch that made passersby either grin or avert their eyes.

My resolve lasted about a week, until I realized that I had an out-of-town trip in my future, a Penthouse expense account junket to the Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Mecca of the dirty weekend, a city made for cheating hearts. “This is really, really it,” I fooled myself, “three nights with Jeff in the Holiday Inn, clean sheets and towels, room service…it will be the perfect ending.”

Holiday Inn, Las Vegas.

Of course it wasn’t. But the champagne was losing its fizz, my guilty conscience turning vinegary.

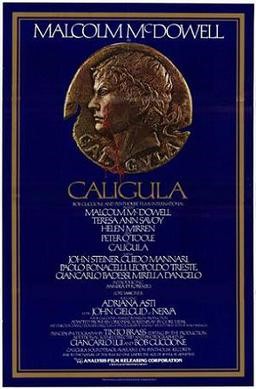

A few weeks after Las Vegas, the Penthouse editorial staff was summoned by our boss, Jim Goode, to his office, always an evil omen. “Caligula,” intoned Jim. “It’s finally going to open.”

Caligula was the fabled, almost mythical motion picture that we had been hearing about forever, a cinematic epic featuring Bob Guccione’s penchant for fake Roman anything, large-breasted girls engaging in deviant sex, and out-of-work British actors, wooed by oversized checks. The magazine had already run dozens of articles hyping the film, as well as several pictorials of “The Girls of Caligula” taking off their togas to veni, vidi, vici. (Uncovered by Penthouse were the lawsuits from both screenwriter Gore Vidal and the original director desperately trying to extract their names from this pornographic debacle.) From the stories and movie stills, it seemed like it was as if it wasn’t enough for the Roman Empire to fall, Caligula had to kick it in the nuts on its way down.

“And…” here Jim looked utterly defeated, “we all have to go to see it.” Everyone in that room suddenly developed plans for their rest of their lives, but there was no escape. The staffs of Penthouse, Omni, Forum, and Variations (really, really deviant junk) were marched up Third Avenue like POWs on their way to Bataan, only more unhappy. At the door to the Trans Luxe Theatre, re-christened the Penthouse Theatre in honor of its round-the-clock showings of Caligula for the next six months, come hell or high water or the Catholic Legion of Decency, was a stern-faced woman taking names.

I managed to nap through the unsimulated sex scenes, but was woken by the sound of gagging. I caught a soul-scarring glimpse of an early Roman bulldozer shearing off the heads of vertically-buried slaves, before snapping my eyes shut again. My best pal Annie, seated next to me and in danger of having the gagger behind us puke on her, bravely stood and headed up the aisle towards freedom, tailed by the woman with a clipboard.

I found Annie outside on her tenth sanity-reviving Newport and we headed back down Third to P.J. Clarke’s and the relief of alcohol. I felt as soiled as I had back when I was editing Penthouse letters. I was worse than Caligula’s horny cousin, Messalina (a role played with the skill of a potted plant by Penthouse Pet Anneka di Lorenzo, who later became another litigant against Guccione, then drowned under suspicious circumstances); at least she was an honest whore. I cracked.

I put my arms and head down on the bar and wept. I bawled, “I’m a horrible person! I’ve been cheating on Michael for months.”

“I know,” said Annie, and patted my back. “With Jeff.” Wait, what? The tears were sucked back in and I straightened up.

“You know?”

Annie sighed, “Gay, everybody knows.” I started crying again.

“What do they think?”

“They all think you’re an idiot.” Annie answered. “I think you better move in with me.”

A coward to the end, I did not tell Michael why I was leaving. I called him from Annie’s that night. “I’ll come by tomorrow to pick up my stuff.”

My stuff was waiting for me, strewn about the courtyard, slowly being covered by a freak late October snowfall. It looked like the crime scene I knew it was. My clothes were heaped in a pile directly below our bedroom window. It was harder to find my jewelry, which had sunk into the snow; my silly “Gay” necklace from Mexico vanished forever. Michael had tossed the LPs he decided were mine like Frisbees from the second floor; some of them were intact in their soggy cardboard sleeves. He seemed to have aimed my cosmetics at the iced-over concrete fountain in the center of the courtyard, which was spattered with broken glass, creams, and lotions; there was still perfume in the air. I picked up a silvery canister that had survived with only a dent; it was the scent Jeff liked on me best, Eau de Charles of the Ritz.

Eventually one of Michael’s multitude of friends let the truth slip. I am thankful that Michael was not a Russian romantic in the Tolstoy tradition. There were no pistols at dawn, no one crushed under a subway train.

Annie’s apartment provided only a limited refuge for me. Breaking up with Michael was not enough; if I was going to be with Jeff, I needed a clean slate, a different life where I was not reminded thirty times a day of what a heel I was, how I had betrayed the dearest man alive, whose only faults were that he hated the outdoors and liked to take a drink.

Jeff had a vision quest. He was going to be a running back with the Falcons; he would train in Atlanta for a few months to get ready for the team’s walk-on tryouts. Jeff had played football in college, before leaving the program to follow vegetarianism, the Dead, and the Rainbow Family. He had seen Rocky too many times. Now he was starring in the role of the contender with heart who just needs one shot. All Jeff was missing were the turtles.

I had no idea what the actual chances for success this plan had. Could a guy who topped off at 5’9” and 145 pounds get into the NFL? It seemed no more unlikely than my own half-pint stab at modeling. I was besotted, desperate to make a getaway, and Atlanta started to sound romantic; like “Lolita” its three syllables tripped from my tongue like a kiss.

We bought a pick-up truck for $600. I loaded my surviving possessions on top of Jeff’s things and we headed south, looking for all the world like the Clampett family, especially after the gale-force gusts on the Pulaski Skyway ripped the tarp covering our worldly goods free from our amateurish knots. I turned around and through the small window in the back of the truck watched the square of blue plastic sail off into the sky, while the dreaming spires of Manhattan dissolved in the mist.

Gay Haubner is taking a hiatus from her weekly series. Look for occasional updates in the future.

Big Birthday Style: Will Smith Turns 50

Now, this is the story all about how

The entertainment business got turned upside down.

It’ll only take a minute for us to share

How a Philly kid became a rapper, movie star, and Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

We’ll spare you more since you almost certainly have the theme song trapped in your head, but it’s for a good reason. Will Smith, start of music, television, and film, turns 50 today. That’s right; Big Willy is the Big 5-0.

Willard Carroll Smith, Jr. was born in Philadelphia in 1968. Smith grew up in a family of four kids. His mother was a school board administrator and his father was an Air Force veteran who worked as a refrigeration engineer. Like many kids of his age group, he was drawn to the sound of hip-hop that emerged on the East Coast in the early ’70s.

Smith didn’t know his life would change when he met Jeffrey Townes in 1985. Townes, who used the stage name “DJ Jazzy Jeff,” was DJing at a house party, but his hype man hadn’t showed. Smith stepped up to the microphone and their partnership fell into place. By 1986, the duo, now named DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, was putting out work on local label Word Up; Smith defied the convention of the time by deciding to “work clean” and avoid swearing in his lyrics. Jive Records caught wind of the pair and snatched them up, re-releasing their debut album Rock the House in 1987.

The music video for “Parents Just Don’t Understand” by DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince

The following year, lightning struck. Their second album, He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper, yielded the smash hit “Parents Just Don’t Understand.” The tune went to #12 on the Hot 100 and won the first Grammy for Best Rap Performance. The album went as high as #4 and sold over 3 million copies. With their conversational style and colorful videos featuring Smith’s comedic persona, the duo quickly became stars. Unfortunately, Smith would run afoul of the IRS for underpayment of income tax; he was in dire financial straits when he was offered the chance to audition for the show that would become The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

The opening sequence and theme song to The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

Debuting in 1990, the show quickly became a hit. Buoyed by an infectious theme song The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air followed Smith’s eponymous, but fictionalized, character as he moved to the West Coast to live with his rich aunt, uncle, and cousins. The classic fish-out-of-water premise allowed Smith to use elements of his stage persona in the show, as well as his natural charm, setting up culture clashes best realized in his interactions with his Uncle Phil (James Avery) and his cousin, Carlson (Alfonso Ribeiro). The show ran for six seasons and continues to be a solid performer in syndication.

During the run of the series, Smith continued to make music and branch into films. His first hit film, Bad Boys in 1995, set the table for a huge action-hero run. The following year, he headlined Independence Day, a major worldwide hit that become, for a time, the second-highest grossing film of all time. It helped set what would be Smith’s rep as “Mr. Fourth of July;” that is, for a few years in a row, Smith’s big-budget action films would debut on the Fourth of July weekend to big box office. That trend continued with Men in Black in 1998 and Wild, Wild West in 1999 (while it tanked long term, it had a strong opening).

Smith managed to create tremendous synergy between his acting and music. His solo debut album, Big Willie Style, delivered five hit singles beginning in 1997. One of those, Men in Black, was recorded to go along with the pending film; it won Smith a 1998 Grammy for Best Solo Rap Performance. He also recorded a title track for Wild, Wild West that he released on his next album, Willennium.

The trailer for the film Ali, directed by Michael Mann.

On film, Smith reached for more serious work and was rewarded for his efforts when he played Muhammad Ali in Ali in 2001; he was nominated for both the Academy Award and the Golden Globe for Best Actor. In the years since, Smith has worked steadily with a larger focus on film and production than music. His last album was released in 2005, but he’s acted in 17 films since Ali and has three scheduled for release in 2019. Smith’s biggest hit of late was 2016’s Suicide Squad, based on the DC Comics series about super-villains forced to take missions for the government; Smith played Floyd Lawton, aka Deadshot, a morally complex hitman. A sequel is pending.

During a 2012 appearance on The Graham Norton Show, Smith proved he still remembers that famous theme song.

Today, Smith continues to enjoy a high profile in entertainment. His wife, actress and producer Jada Pinkett-Smith, is a frequent production partner, and the couple are shareholders in the Philadelphia 76ers NBA franchise. Smith’s son, Trey, from an earlier marriage, is a DJ and rapper. Smith and Pinkett-Smith’s children Jaden and Willow have also become performers and social media celebrities.

Not one to forget his friends, Smith has produced projects that have furthered the careers of others in his orbit. He has produced films like Eddie Murphy’s Showtime and the 2014 remake of Annie. Smith also served as Executive Producer for fellow rapper Queen Latifah’s talk show. He helped launch the musical career of his Fresh Prince co-star Tatyana Ali, appearing on her 1998 track “Boy You Knock Me Out” and having her guest on his own “Who I Am.” Smith and his family support a number of charitable causes; they founded the Will and Jada Smith Family Foundation to serve inner-city communities with educational and business-incubation opportunities..

Smith’s story contains many elements of the classic American success fable. He stuck to his vision of his music and how he should present himself. He sought bigger challenges and found bigger success. Despite making sequels, he wasn’t content to repeat himself in his work. He’s used his success to create opportunities and elevate others in both film and music. That’s how he became the Prince of Bel-Air (and Hollywood, and the Grammys, and whatever he chooses to do).

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

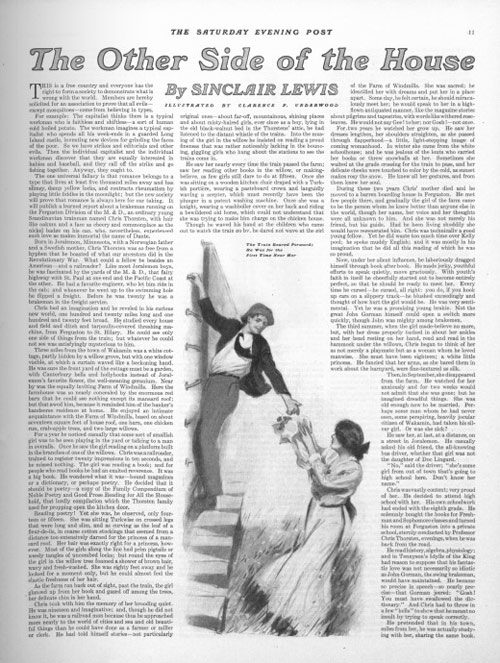

“The Other Side of the House” by Sinclair Lewis

Editor George Horace Lorimer accepted Sinclair Lewis’s short story “Nature, Inc.” from The Saturday Evening Post’s “slush pile” of manuscripts in 1915 and began a prolific relationship between the satirical author and the magazine. Lewis’s novel Babbitt (1922) brought this kinship to a screeching halt due to its critique of business and the middle class. Lorimer wrote an unkind review of the book, and Lewis was left out of the Post for years to come.

In “The Other Side of the House,” a Minnesota trainman initiates a peculiar courtship with a student along his route. When they finally meet, one high-stakes decision to stay or go will set them on track for love or loneliness.

Published on November 27, 1915

This is a free country and everyone has the right to form a society to demonstrate what is wrong with the world. Members are hereby solicited for an association to prove that all evils — except mosquitoes — come from believing in types.

For example: The capitalist thinks there is a typical workman who is faithless and shiftless — a sort of human cold boiled potato. The workman imagines a typical capitalist who spends all his weekends in a guarded Long Island castle, inventing new devices for grinding the faces of the poor. So we have strikes and editorials and other evils. Then the individual capitalist and the individual workman discover that they are equally interested in babies and baseball, and they call off the strike and go fishing together. Anyway, they ought to.

The one universal fallacy is that romance belongs to a type that lives at least five thousand miles away and has slimsy, damp yellow locks, and contracts rheumatism by playing little fiddles in the moonlight; but the new society will prove that romance is always here for our taking. It will publish a learned report about a brakeman running on the Ferguston Division of the M.&D., an ordinary young Scandinavian trainman named Chris Thorsten, with hair like oakum and a face as cheery and commonplace as the nickel badge on his cap, who, nevertheless, experienced such love as makes immortal the name of Dante.

Born in Joralemon, Minnesota, with a Norwegian father and a Swedish mother, Chris Thorsten was so free from a hyphen that he boasted of what our ancestors did in the Revolutionary War. What could a fellow be besides an American — and a railroader? Like most Joralemon boys, he was fascinated by the yards of the M.&D., that fairy highway with St. Paul at one end and the Pacific Coast at the other. He had a favorite engineer, who let him ride in the cab; and whenever he went up to the swimming hole he flipped a freight. Before he was twenty he was a brakeman in the freight service.

Chris had an imagination and he reveled in his curious new world, one hundred and twenty miles long and one hundred and twenty feet broad. He studied every house and field and ditch and tarpaulin-covered threshing machine, from Ferguston to St. Hilary. He could see only one side of things from the train; but whatever he could not see was satisfyingly mysterious to him.

Three miles from the town of Wakamin was a white cottage, partly hidden by a willow grove, but with one window visible, at which a curtain waved like a beckoning hand. He was sure the front yard of the cottage must be a garden, with Canterbury bells and hollyhocks instead of Joralemon’s favorite flower, the well-meaning geranium. Nearby was the equally inviting Farm of Windmills. Here the farmhouse was so nearly concealed by the enormous red barn that he could see nothing except its mansard roof; but that awed him, because it reminded him of the banker’s handsome residence at home. He enjoyed an intimate acquaintance with the Farm of Windmills, based on about seventeen square feet of house roof, one barn, one chicken run, crab-apple trees, and two large willows.

For a year he noticed casually that some sort of smallish girl was to be seen playing in the yard or talking to a man in overalls. Once he saw the girl reading on a platform built in the branches of one of the willows. Chris was a railroader, trained to register twenty impressions in ten seconds, and he missed nothing. The girl was reading a book; and for people who read books he had an exalted reverence. It was a big book. He wondered what it was — bound magazines or a dictionary, or perhaps poetry. He decided that it should be poetry — a copy of the Family Compendium of Noble Poetry and Good Prose Reading for All the Household, that lordly compilation which the Thorsten family used for propping open the kitchen door.

Reading poetry! Yet she was, he observed, only fourteen or fifteen. She was sitting Turkwise on crossed legs that were long and slim, and as curving as the leaf of a fleur-de-lis, in coarse cotton stockings that seemed from a distance too extensively darned for the princess of a mansard roof. Her hair was exactly right for a princess, however. Most of the girls along the line had prim pigtails or weedy tangles of uncombed locks; but round the eyes of the girl in the willow tree foamed a shower of brown hair, wavy and fresh-washed. She was eighty feet away and he looked for a moment only, but he could almost feel the elastic freshness of her hair.

As the farm ran back out of sight, past the train, the girl glanced up from her book and gazed off among the trees, her delicate chin in her hand.

Chris took with him the memory of her brooding quiet. He was nineteen and imaginative; and, though he did not know it, he was a railroad man because thus he approached more nearly to the world of cities and sea and old beautiful things than he could have done as a farmer or miller or clerk. He had told himself stories — not particularly original ones — about far-off, mountainous, shining places and about misty-haired girls, ever since as a boy, lying in the old black-walnut bed in the Thorstens’ attic, he had listened to the distant whistle of the trains. Into the musing of the girl in the willow he insisted on reading a proud fineness that was rather noticeably lacking in the bouncing, giggling girls who hung about the stations to see the trains come in.

He saw her nearly every time the train passed the farm; saw her reading other books in the willow, or making believe, as few girls still dare to do at fifteen. Once she was sitting on a wooden kitchen chair draped with a Turkish portiere, wearing a pasteboard crown and languidly waving a scepter, which must recently have been the plunger in a patent washing machine. Once she was a knight, wearing a washboiler cover on her back and riding a bewildered old horse, which could not understand that she was trying to make him charge on the chicken house.

Though he waved his hand at the children who came out to watch the train go by, he dared not wave at the girl of the Farm of Windmills. She was sacred; he identified her with dreams and put her in a place apart. Some day, he felt certain, he should miraculously meet her; he would speak to her in a high-flown antiquated manner, like the magazine stories about pilgrims and tapestries, with words like withered roseleaves. He would not say Gee! to her; nor Gosh! — not once.

For two years he watched her grow up. He saw her dresses lengthen, her shoulders straighten, as she passed through flapperhood — a little, light-stepping image of coming womanhood. In winter she came from the white schoolhouse; and he was jealous of the louts who carried her books or threw snowballs at her. Sometimes she waited at the grade crossing for the train to pass, and her delicate cheeks were touched to color by the cold, as sunset makes rosy the snow. He knew all her gestures, and from them knew her soul.

During these two years Chris’ mother died and he moved to a barren boarding house in Ferguston. He met few people there, and gradually the girl of the farm came to be the person whom he knew better than anyone else in the world, though her name, her voice and her thoughts were all unknown to him. And she was not merely his friend, but his guide. Had he been living shoddily she would have regenerated him. Chris was technically a good young fellow. Yet he did waste too much time over Kelly pool; he spoke muddy English; and it was mostly in his imagination that he did all this reading of which he was so proud.

Now, under her silent influence, he laboriously dragged himself through book after book. He made jerky, youthful efforts to speak quietly, move graciously. With youth’s faith in itself he cheerfully started out to become entirely perfect, so that he should be ready to meet her. Every time he cursed — he cursed, all right; you do, if you hook up cars on a slippery track — he blushed exceedingly and thought of how hurt the girl would be. He was very sentimental. Yet he was a promising young brakie. Not the great John Gorman himself could open a switch more quickly, though John was mighty among brakemen.

The third summer, when the girl made-believe no more, but, with her dress properly tucked in about her ankles and her head resting on her hand, read and read in the hammock under the willows, Chris began to think of her as not merely a playmate but as a woman whom he loved man-wise. She must have been eighteen; a white little princess. He fancied that her arms, as she bared them in work about the barnyard, were fine-textured as silk.

Then, in September, she disappeared from the farm. He watched for her anxiously and for two weeks would not admit that she was gone; but he imagined dreadful things. She was old enough now to be married. Perhaps some man whom he had never seen, some perspiring, heavily jocular citizen of Wakamin, had taken his silver girl. Or was she sick?

He saw her, at last, at a distance, on a street in Joralemon. He casually asked his old friend, the all-knowing bus driver, whether that girl was not the daughter of Doc Lingard.

“No,” said the driver; “she’s some girl from out of town that’s going to high school here. Don’t know her name.”

Chris was vastly content; very proud of her. He decided to attend high school with her. His own schoolwork had ended with the eighth grade. He solemnly bought the books for Freshman and Sophomore classes and turned his room at Ferguston into a private school, sternly conducted by Professor Chris Thorsten, evenings, when he was back from the road.

He read history, algebra, physiology; and in Tennyson’s Idylls of the King had reason to suppose that his fantastic love was not necessarily so idiotic as John Gorman, the swing brakeman, would have maintained. He became so precise in speech — so nearly precise — that Gorman jeered: “Gosh! You must have swallowed the dictionary.” And Chris had to throw in a few “hells” to show that he meant no insult by trying to speak correctly.

He pretended that in his town, miles from her, he was actually studying with her, sharing the same book. He could feel one elbow grind on the table; feel the other arm, as he turned the leaves, faintly touch her side. The light would slide down her smooth cheek to her throat as she glanced from page to page, he imagined.

It was in his high school reading that he first learned the story of Dante — which he innocently pronounced Dant. He traced himself in the lonely poet; the girl of the farm in the deathless Beatrice. All winter he asserted to himself that he was the exiled Italian, wandering down the damp corridors of ancient palaces. He was not, though. And the Minnesota winter was not really a season of rains and poetic melancholy.

Chris, on the cars, was a lumpy figure in a duck-lined Mackinaw coat and huge red mittens. Two cars away he could scarcely be seen through the blizzard. When the northwest gales stopped, and the sun glared on miles of snowdrifts that stretched from the track to the steel-blue sky, the thermometer dropped to forty degrees below zero and the coupling pins stung his hand even through mittens. But he was Dante and also a high school prize winner, and declined to admit that he was cold.

It is probably true that Chris Thorsten’s poetry was inferior to that of Dante; but, as regards practical common sense, he was a genius compared with that self-satisfied, wireless lover. He knew that if he was ever to care for the girl he had to climb beyond brakemanhood. He saw no reason why he should not be General Traffic Manager some day; but he saw plenty of reasons why he was not likely to be, unless he got into the General Offices — which the railroaders call the white-collar route. He added stenography and typewriting to his studies, and read books — one book, anyway — about railroad finance and management.

The girl seemed so constantly with him that for a second he was not surprised when, on a May day — with the poplars and silver birches in foliage, the prairie sloughs like fields of bluebells, and lady-slippers out in the tamarack swamps — he saw her again, standing between the willows, at the Farm of Windmills. Instantly his hand shot out as though it was a live, winged thing flying to her. For the first time in nearly four years of a love like worship he was waving to her. She responded — a flick of her hand; a slight turning of her shoulders in her white blouse; while the sun caught the movement of her piled brown hair.

He stretched out his arms, standing on a box car, revealed to her as a figure against the cornflower sky, in the attitude of crucifixion — and of utter happiness. His floppy corduroy trousers and black sateen shirt and black slouch hat fluttered buoyantly as the breeze whisked about him.

He wanted to tell someone all about it; but — the conductor chewed tobacco, and the front brakeman wore a celluloid button stamped, “Kiss me, kid!” and John Gorman had a laugh like a sick horse. Chris compromised by shouting, “Great day, by golly!” to the operator when they reached the Wakamin Station. By which he meant to indicate that the year was at spring and his sweetheart slim and winsome and kind; that life was exciting and the Wakamin Station more glorious than all the stations of London or Rome or fairyland.

In this last he was absurdly exaggerating. The Wakamin Station presumably answered the purpose, but it was not esthetic. On the splintery platform, so sun-soaked that the planks smelled of pine forests and resin oozed out in amber drops, one case of empty beer bottles reposed desolately. Under the platform all the homeless newspapers and orange peels of the neighborhood found a resting place. Yet here Chris shouted his happiness.

He waved to the girl again the day following. She did not respond. The third day she was not in sight. The fourth, she fluttered a handkerchief at him. The fifth, she was reading in the hammock and did not look up. The sixth, he was off duty. The seventh, she did not appear. The eighth, she answered with a gesture of her delicate fingers like the waver of lace in a draft.

So it went for two weeks, and he tried to assay her replies scientifically.

Once, when they were sidetracked for two hours, John Gorman caught him plucking the petals of a daisy and growling: “Loves me — loves me not!” Chris had to lie vigorously — that he was trying to guess his chances of winning Doc Nickerson’s shotgun raffle — to save himself from the reputation of being a young lover.

There is probably no legal reason why all lovers should not be confined in asylums. For more than two weeks it did not occur to Chris that, though he knew the girl better than he knew any other person in the world, and though she had waved to him, yet there was no reason why she should distinguish his greeting from any other careless gesture by a passing trainman.

When he did forget moonshine long enough to make this revolutionary discovery, he spent an evening at Ferguston in composing a bouquet for her. He discerningly stole daffodils from his landlady’s garden, and from Old Man Bromenshenkel, the vegetable man, he bought irises, purple and golden; and he wrapped the bouquet in silver-gilt paper, with all of the lover’s fumbling anxiety over his first gift. Thrice he unwrapped it — once to see whether the stalks were fastened, and once to put in a note, “Greetings from a lonely brakie!” and once to remove that note, which he rended and utterly destroyed.

Next day it was his trick on watch in the caboose cupola. He thrust his arm — unromantic in its sleeve of blue flannel fuzzy with lint — through the window, whirled it violently, and let the bouquet fly toward her. The girl, not very poetically engaged in feeding pigs, stared perplexedly and did not give response. The bouquet landed in the weed-filled ditch beside the track.

When the train passed next day Chris saw the gilt paper of his gift still lying among the weeds, a forlorn thing, with the gay cover smashed from its fall.

Hurt, amazed, he stared at it, then peered at the farmyard. As in her childhood days, the girl was reading on the airy platform among the willow boughs; but round her slim, fine legs a long skirt was swathed and her fingers pressed her temples as though her eyes were a little tired.

She looked up, the sunlight that came through the leaves checkering her hair with light and shadow, and let her quiet glance dwell on the train. He curtly saluted her, hand to forehead, and she waved just as the train exasperatingly bore him away.

“I wonder whether she knew it was a bouquet for her?” he meditated.

That night he prepared another bouquet of the brightest irises he could find, and he flung them unwrapped. He saw her pointed chin rise until her throat shone above her collar as, with surprised eyes, she followed the arc of the flying flowers. She started to run forward.

The flowers were gone next day, and from the tree house she peeped shyly at the train.

Roses, as they came into bloom, sweet peas that were like her fresh cleanness, pansies and peonies, he gave her. He had to hide them in his lunch pail, in his pocket — even among the farm machinery loaded on flat cars — to conceal them from the other trainmen.

She was standing by the fence one morning of passing; her fingers were nervously pinching the rusty barbed wire; with a perturbed, lovely excitement she was examining the whole train. He was impudently perched on a brake on a box car. He sprang up; his hat came off. His cropped, broom-colored hair and the pleasant evert tan of his Norse face had something of the sturdy boyishness of a young knight. He awkwardly bowed to her, and from his pocket he brought out a careful though slightly mussy little bunch of pansies. A smile transformed the searching seriousness of her face; then, as though she were again the little girl, she ran away.

She waved to him always after that. Once or twice there were girls with her, visitors apparently, and she motioned with a secrecy that she evidently enjoyed. He saw her studying him from the willow, her little high-crowned head cocked on one side.

He knew now that her greetings were for him alone. Once, when he was in the cupola, he saw the front brakeman signal to her. She stared at the intruder and did not move; but when the caboose came opposite her, and Chris waved, she was like one waking from a brown study.

At last he sent her a book by his aerial post — Keats’ Poems, in a red-line edition — and in it this note:

Please let me send you this book. For years now I have been watching you read; I guess there are not many girls along here who read. I love to read too; even a brakie loves to read sometimes. I read Dickens and Hall Caine, and lots of magazines. So I wanted to send you this book. If you like it just wave it once as I go by, and I will know I have not been fresh in giving it to you, because we both like to read. Honest, I do not want to be fresh. I have got all kinds of respect for the lady who reads such interesting-looking books in the willows.

YOUR FRIEND OF THE FREIGHT TRAIN.

P. S. The librarian of the Saint Hilary Public Library — she is a highly educated woman — says she is sure you will like this book. It is fine poetry. I do not read much poetry myself, but I appreciate it.

He was gloomy after giving her the book. Perhaps she would scorn it. He pictured her with eyes flashing, foot stamping — like the heroine of Humble Hearts, which had played under canvas at Ferguston; he fancied her exclaiming: “Sir, how dare you!”

Next day she stood at the fence again, flushed, agitated, her eyes shining. As he came abreast of her she pulled the book from under her arm, hesitated, then waved it timidly.

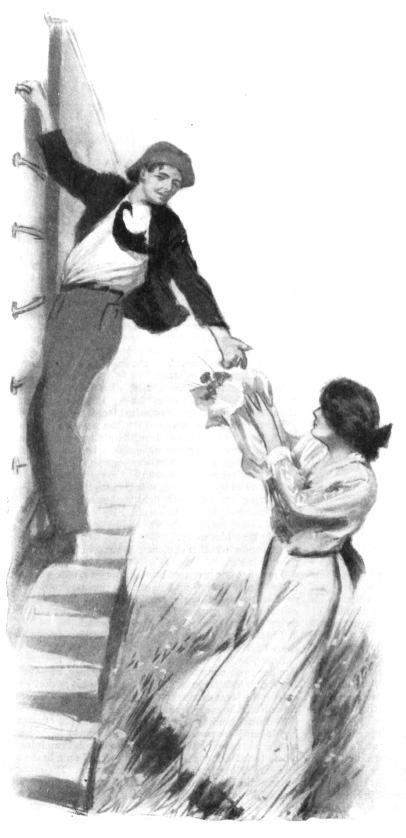

After two weeks, during which she did not come so far as the fence, though he sent her another book, he looked ahead and saw her down beside the track, balancing a ball of paper and watching intently. She motioned up at him with the bundle. He skipped down the iron ladder on the side of the box car and leaned far out, precariously holding the ladder with one hand, the other hand outstretched toward her, smoke and cinders storming round them both.

The train roared forward; he was carried toward her — was for the first time near her parted, expectant lips. She was holding out the bundle. He caught it, slammed it to his breast to hold it safe, while in the sudden jerk of the action he almost lost his grip and nearly fell from the ladder. He heard the cruelly grinding trucks. His whole body contracted with the fear of falling; but instantly he got hold of himself and over his shoulder bowed to her gracefully — that is, as gracefully as a man hanging with feet and one hand to a ladder on the side of a jouncing train, swinging with the motion, can reasonably be expected to bow.

As Dante would have opened a scroll from Beatrice, so a panting, dusty brakeman sat on a box car and undid the folds of a bunched newspaper.

There were shaggy russet dahlias setting off the purple of wild asters — and among the flowers this note:

Dear Unknown Friend:

Indeed I do love to read books, as you said; and I want to thank you many times for making my summer happier. It might have been quite a lonely summer if I hadn’t had somebody to sort of talk to as you went by. There are not many books round here, so I appreciated your thoughtfulness; and, oh, indeed, I did not feel you were fresh, like you said. I am going back to school. I leave this afternoon, but could not go without thanking you. I hope you will not have a bad winter; it must be hard on trains in snow. I will think of you there.

THE GIRL THAT READS.

“I will think of you there.” That was the phrase he kissed most frequently.

He studied her handwriting — the precise script of a woman who reads much and writes little. In the slender loops of the l’s he saw her own self.