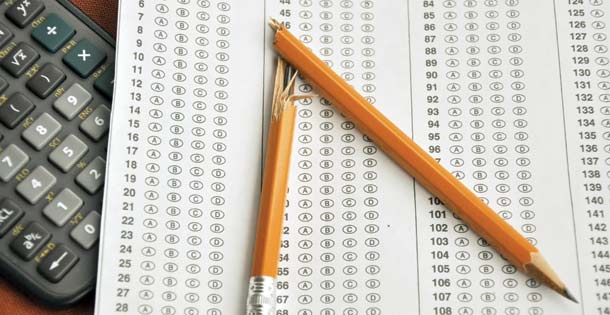

Our nation’s test obsession is making American schools into unhappy places. Benchmark, practice, field, and diagnostic exams are raising the total number of standardized tests up to an average of 133 by the 12th grade. Physical education, art, foreign languages, and other vital subjects are going on the block in favor of more drilling on core tested subjects. In one Florida high school, a student reported that her brand-new computer lab was in use 124 days out of the 180-day school year for testing and test prep.

Like many other Gen X and Gen Y parents, I’m committed to sending my daughter to a public school, both because private school would be a financial stretch for our family and because I have a strong personal belief in public schools as the building block of democracy. But I can’t ignore what I’ve been hearing.

Parents are sending kids to public schools with high test scores and great reputations only to come up against an unyielding rigidity that I trace directly back to tests. In poorer districts, teaching to the test is even more likely to replace the other activities that students desperately need. The charter schools that are supposed to provide educational choice are captive to data-driven decision making that results in even more test score obsession to please lawmakers and private donors.

The word of the day is anxiety. Here are some of the problems:

1) We’re testing the wrong things.

A flood of recent research has supported the idea that creative problem solving, oral and written communication skills, and critical thinking, plus social and emotional factors including grit, motivation, and the ability to collaborate, are just as important in determining success as traditional academics. All of these are largely outside the scope of most standardized tests, including the new Common Core–aligned tests. Scores on state tests do not correlate with students’ ability to think.

2) Tests waste student time and taxpayer money.

Not only do standardized tests address only a fraction of what students need to learn, we’re spending ages doing it. Time given to standardized tests includes practice tests, field tests, prep days, Saturday school, and workbooks for homework. Reports from across the country suggest that students spend about three days taking state tests in each of grades 3-10, but up to 25 percent of the school year engaged in testing and test prep.

That’s the time factor. What about money? A 2012 report by the Brookings Institution found $669 million in direct annual spending on assessments in 45 states, or $27 per student. But that’s just the beginning. The cost rises up to an estimated $1,100 per student when you add in the logistical and administrative overhead (e.g., the extra cost of paying teachers to administer the tests and offer help as students prepare for them).

Many informed observers say that we’d do better to have more expensive tests, and fewer of them. “The reliance on multiple-choice tests is a very American obsession,” says Dylan Wiliam, an expert on the use of assessments that improve classroom practice. “We think nothing of spending $300-$400 on examining kids at the end of high school in England.” It’s a case of penny wise and pound foolish, critics like Wiliam say: You waste billions of dollars and untold hours by distorting the entire enterprise of school, preparing students to take crummy multiple-choice tests that cost only $25 to grade.

3) They are making students hate school.

A little bit of stress can be healthy and motivational. Too much, or the wrong kind, can be damaging and toxic. When you put teachers’ and principals’ jobs on the line and turn up the heat on parents, students catch the anxiety like a bug. It’s like burning thirsty plants under a magnifying glass in the hope that they will grow faster under scrutiny.

Especially in the elementary grades, teachers and parents across the country report students throwing up, staying home with stomachaches, locking themselves in the bathroom, crying, having nightmares, and otherwise acting out on test days.

4) They are making teachers hate teaching.

High-stakes standardized tests deprofessionalize teaching because they give outside authorities the final say on how teachers should do their jobs. The testing company determines the quality of teachers’ performance. In judging students’ progress, the law gives test scores more weight than the observations of people who spend time with the kids every day.

How do you judge a teacher based on their students’ test scores? Not very well. Obviously, you can’t take a teacher whose students are the children of Hispanic migrant workers and simply compare their test scores with those of the teacher teaching the rich kids up the hill to figure out who is a better teacher. In a 2011 paper, “Getting Teacher Evaluation Right,” Stanford researcher Linda Darling-Hammond and three other education researchers concluded that ratings for individual teachers are highly unstable, varying from year to year and from one test to another.

5) They penalize diversity.

No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the major testing law, was intended to “close the achievement gap.” It sought to hold schools accountable, not just for results averaged over all students, but for the performance of each historically lower-performing group of students: the poor, African Americans, Hispanics, English-language learners, and those with a learning disability. The unintended consequence of that laudable intention is that schools that serve the poor and ethnic minorities are more likely to fail NCLB tests and to be punished or closed. Granted, school reorganizations sometimes mean real improvement, but in all cases, they disrupt neighborhoods and social networks, which is why they have sparked protests from Detroit to Newark to Chicago to Houston to Baltimore.

6) They cause teaching to the test.

In an ideal world, better test scores should show that teaching and learning are getting better. But standardized tests have never delivered on that simple promise. A first-grade teacher described on a blog what teaching to the test had done to her and her students: “Standardized tests actually make students stupid. Yes, stupid. … In my zeal to get administrative scrutiny off me and my students, I mistakenly thought that if I give [administrators] the test results they want, then I could do what I know was best for my students. To that end, I trained my students to do well in these tests. I taught them to look for loopholes; to eliminate and guess; to find key words; to look for clues; in short, to exchange the process of thinking for the process of manipulation.”

“We’re seeing schools emphasize literacy skills and math to the detriment of civics, social studies, the arts, and anything creative,” Wayne Au at the University of Washington Bothell, author of a study on the topic, told me.

7) High stakes tempt cheating.

The simplest way to improve a school’s test scores is a No. 2 pencil with an eraser. You take the test papers, erase the students’ incorrect answers, and bubble in the correct ones. According to a GAO report issued in May 2013, officials in 33 states confirmed at least one instance of cheating in the 2011 and 2012 school years, and in 32 of 33 cases, states canceled, invalidated, or nullified test scores as a result of cheating.

8) They are full of errors.

Mistakes on tests are widespread. If your child starts taking math and reading tests in third grade, by the time she gets to seventh grade, odds are she will have taken at least one test on which her score was bogus. In a year-long investigation published in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in September 2013, Heather Vogell studied more than 92,000 test questions given over two years to students in 42 states and Washington, D.C. The investigation revealed that almost one in ten tests nationwide contained significant blocks of flawed questions — 10 percent or more of the questions on these tests had ambiguous or wrong answers. In other words, the percentage of flawed questions is high enough in one out of ten tests to place the fairness of the results in doubt.

If anything, essay questions on standardized tests are even more questionable than multiple choice. They are supposed to be the place to demonstrate deeper learning and communication skills. A series of experiments by Les Perelman at MIT has shown that nonsensical essays could get high scores from graders if they contained the right vocabulary and were the proper length.

Who is to blame for America’s high-stakes testing obsession, unique in history and in the world? Testing companies are collecting the cash, and politicians are passing the laws, but as parents, we are the ones who have allowed this to happen.

So it’s time to ask some tough questions that get down to root causes. What if my kid doesn’t score as high as she might on a test? What is it I’m really afraid of? That she’s not really all that special? That the world won’t realize he’s as wonderful as I know he is? That she won’t be successful? That his life will be ruined if he doesn’t get into this kindergarten or that college? That he’ll be missing out on his best chance at happiness? Or am I really afraid of how that score will reflect on me and the job I’m doing?

“I’m hoping that people will pay attention to these issues,” says psychologist Suniya Luthar. “This is about you and me, our kids, so we had better pay attention.”

Finding and forming connections with like-minded parents is essential. So is enlisting our kids’ teachers as allies. I’m firmly convinced that a future of fewer tests, better tests, and happier, healthier, more successful kids is well within our grasp. But we all have to work together to create it.

Adapted excerpt from The Test: Why Our Schools Are Obsessed with Standardized Testing — But You Don’t Have to Be by Anya Kamenetz. Copyright © 2015. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Preseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More on education in America:

Online Testing Doesn’t Work

When it comes to exams, this high schooler wants to stick with good old-fashioned pencil and paper. Read more >>

American Schools in Crisis

A leading educator argues that current reforms are short sighted, wrong headed—and bound to fail. Read more >>

Teaching to the Test Gets an ‘F’

A conversation with Sir Ken Robinson, a leading thinker in the field of education and human potential. Read more >>

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now