September 1 marks the anniversary of the day George Pullman’s sleeper car made its first run on the rail line between Chicago and Bloomington, Illinois.

The date is more than just a turning point in railroad history. The appearance of the Pullman sleeper car wrought changes affecting American business, social class, labor unions, and race relations over the years.

1858:

George Pullman was inspired to build a rail car with sleeping berths after making a miserable overnight journey across New York state in a make-shift sleeping car.

1862:

He formed the Pullman Palace Car Company to build railroad cars in which berths would fold down from the roof at night. During the day, the berths were stowed above, not unlike overhead storage in modern airplanes, and passengers sat in comfortably upholstered seats, enjoying the luxury of wash rooms, chandelier lights, thick carpeting, and heating stoves.

1865:

Public acceptance developed slowly. The Pullman coach received much favorable publicity after Mrs. Lincoln chose a Pullman car to transport her husband’s body back to Springfield.

1866:

The Saturday Evening Post noted in its June 23 issue, “Mr. Pullman, the projector of the sleeping-car improvement in railroad traveling, has just placed on some of the western roads new cars, with conveniences, luxuries, and ornamentation quite in advance of anything yet produced. A novel arrangement of the trucks [wheel assemblies] secures such a steadiness of motion that writing is as easily done as in a home library, and tables are provided for this purpose. One car, the ‘Omaha,’ is furnished with an organ.”

1870:

A Post writer, writing on a trip “Homeward from the Pacific Coast” made an observation about that organ. “We took our place in the luxuriant ‘Pullman Palace.’ There was a parlor organ on board, a poor wheezy out of tune thing, but as we were in the realms of sage brush and alkali again, we managed to make it serve for the getting up of quite a Sunday afternoon concert. What mellifluous sounds were wafted out upon the desert air only those on board that train can tell, but finally the most energetic of our singers were forced to desist because two refractory keys of the upper bank would insist upon singing out above all else, even when not requested to do so by touch of hand.”

1872:

By this year, the Pullman company had 800 cars running on rail lines covering 30,000 miles of country. Pullman continued to introduce luxuries to his cars, including thick carpeting, dark wood interiors, and reclining seats.

1881:

The first Pullman employee moves into Pullman, Illinois, a town owned and operated by the company. In its time, Pullman was hailed as the ultimate, enlightened community for workers. It offered employees clean, well-lit housing with indoor plumbing, gas, sewers, stores, and theaters. The rent was higher than average, but the quality of housing was generally better than in surrounding neighborhoods. The higher living standard came with another price, though. George Pullman maintained absolute control on all organization, events, and publications in his town. He also required all employees—about 3,500 eventually—to live in the company town and follow its rules.

1885:

The April 25th Post marveled at the cost of Pullman luxury:

“Few persons, as they see one of the fast express trains go by, are aware of the value of such a train. What is known as the Royal Limited Express over the Pennsylvania road, as the train is ordinarily made up, represents over $120,000. This is a rather low estimate of one of the fast expresses. Some of the palace cars are worth $18,000 and Pullman palace cars occasionally run that cost in the neighborhood of $30,000.” (That’s the equivalent of $700,000 in 2009 currency.)

1893:

In response to the depression in this year, The Pullman Palace Car Company cut employees’ wages, but didn’t drop the rent it charged employees. When Pullman workers went out on strike, union workers across the nation added their support by walking off their jobs, effectively halting rail traffic. Meanwhile, at the Pullman factory, the strike led to property damage and fights with strike-breaking employees. Ultimately, the Pullman company convinced Washington that the strike was a threat to public safety and interstate commerce. President Cleveland sent in federal troops and forcibly ended the strike in favor of management. The strike leaders were arrested, tried, and sentenced.

1894:

Yet American opinion was not wholly supportive of the government’s actions. A national commission investigated working conditions at Pullman and concluded that the forced community for employees was “unAmerican.” The state Supreme Court eventually ordered Pullman to sell its company town and end its control over worker’s lives.

1935:

The American Federation of Labor broke with its own tradition to recognize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a union of black Americans who serviced the Pullman coaches. For many years, the Pullman Company was the largest employer of black Americans. Black porters on sleeping cars attended passengers’ needs, made up beds, and polished shoes. It was menial work, but it offered one of the few avenues to something like middle-class life to male black Americans.

1940:

The U.S. Department of Justice brought an anti-trust suit against Pullman. It claimed that being the chief manufacturer of passenger cars and the sole agent for tickets on these cars made Pullman a monopoly. The court ordered the Pullman Company to create two separate businesses for manufacturing and passenger-traffic.

1941:

A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, announced to President Roosevelt that he was planning to march on Washington with members of his union and the NAACP—just as the country was struggling to prepare for war. In return for calling off the march, Randolph obtained Roosevelt’s promise to outlaw discrimination on defense-contract work and to pass the Fair Employment Act. (In 1949, Randolph pressured Harry Truman to officially end segregation within the military.)

1943:

The reverses handed to the Pullman company were not so great that it couldn’t thrive during the war years. As a 1943 Post article relates:

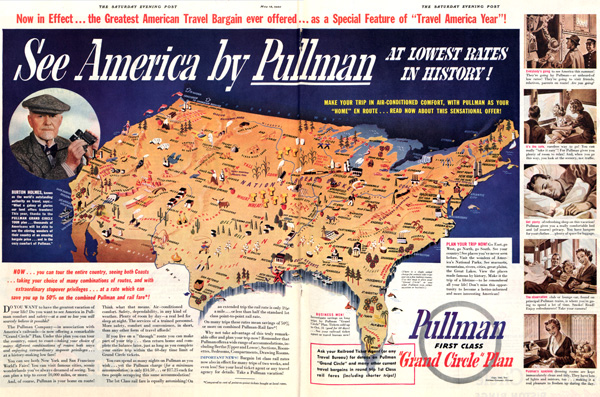

“Pullman’s original pool of sleeping cars has mushroomed to a fleet of more than 7,000 perambulating hotels which last year grossed better than $113,000,000. It is units of this highly mobile pool, distributed to the different railroads to meet hour-by-hour needs, which makes possible the efficient handling of close to 75,000 passengers a day.” Today, the American Transportation Authority estimates that the number of airline passengers, in a single day, can reach 2,000,000.

As late as the 1980s, the Pullman Company was still manufacturing passenger cars for commuter trains. Ultimately, various divisions of the company were sold off to other businesses. Part of the operations, for example, are now part of the Halliburton, while other parts have been subsumed by Halliburton’s chief rival, Washington Group International.

Having weathered the shrinking passenger car industry, the Pullman Company was purchased by Tenneco, and is now in the equally challenged business of manufacturing auto parts.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Sorry to hear that Pullman is, or was, in any way associated with Halliburton !!!