American history is filled with heroes, but only three are honored with national holidays — Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and Martin Luther King Jr. Of these, only the latter two were born in America, and Washington’s birthday also serves as President’s Day to honor all other presidents. Martin Luther King Jr. has his own holiday (although, the state of Virginia combines his holiday weekend with Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson Day).

A dedicated national holiday is a unique honor for an American, particularly when he was regarded with dread and suspicion in his own time.

Civil rights have always been a troublesome issue for a country that is publicly dedicated to equality. But for many years, the fate of minorities in the United States was only a peripheral problem to American society; white Americans could live their lives without ever confronting the problems of racism and segregation.

That began to change in the mid-20th century. The U.S. Federal Government secured the support of black Americans for the war effort by offering them new chances for advancement, both in the military and in military contracting. In 1954, the Supreme Court decided there could be no legal justification for racial inequality. States could no longer justify segregated schools. In 1955 Rosa Parks inspired 50,000 black Americans to protest segregation on buses in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1957 President Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock to enable black students to enroll in the local high school. Black activists staged sit-ins in the 1960s, and Freedom Riders took Ms. Parks’ protest further, testing the government’s willingness to support integration on interstate transportation.

In a relatively short time, the issue of race had moved to center stage. Some white Americans who had always enjoyed the full benefits of their rights had difficulty understanding the black Americans’ impatience and mistrust of the government. And they wondered about the charismatic leader who had emerged from this movement and talked boldly of immediate action. Martin Luther King Jr. made civil rights an issue that could not be ignored or dismissed as racial politics. It was an American issue.

The Post published an article about Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963. Its author, Reese Cleghorn, recognized the need for integration, but he was skeptical about King.

He reported the Birmingham riots as if he had no stake in the conflict between black Americans fighting for their overdue civil rights and white racists who wanted to refuse them. Cleghorn seems to have gathered up every criticism he could find about King — though he was too busy to include the name of his sources.

For instance, he links King with violent black protesters:

“Thus did racial violence come this spring to the most rigidly segregated major city in America. It marked a collision of two power systems, the first represented by Bull Connor, vigorously enforcing laws that preserve the status quo of racial discrimination, the second by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. making a carefully planned assault on those laws and that discrimination.”

He presents King as a dangerous provocateur:

“[King] lighted a fire under the pressure cooker, well knowing that the ‘peaceful demonstrations’ he organized would bring, at the very least, tough repressive measures by the police. And although he hoped his followers would not respond with violence — he has always stressed a nonviolent philosophy — that was a risk he was prepared to take. Two months earlier his No.1 staff assistant, the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, had explained, ‘We’ve got to have a crisis to bargain with. To take moderate approach, hoping to get white help doesn’t work. They nail you to the cross, and it saps the enthusiasm of the followers. You’ve got to have a crisis.'”

King was imperious:

“For these and other reasons, some integrationist leaders felt that King had blundered in bringing crisis to Birmingham. It was not the right place, they maintained; this was not the right time; and mass marches to fill the jails—a tactic that bears King’s personal brand—was not the right tactic. Further, King had gone into Birmingham not only against the advice of these leaders but without even informing them. ‘That’s just arrogant,’ one said in exasperation.”

King was self-serving:

“Other detractors within the desegregation movement have bitterly accused King of tackling Birmingham primarily to raise money and to keep his name and his organizations, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), out in front on the teeming civil-rights scene.”

He was playing with fire:

“King’s magic touch with the masses of Negroes remains. They do not understand the intricacies of his tactics. What they see is a powerful crusader for equality who does something instead of just talking, who sticks lighted matches to the status quo and who is impatient with talk of waiting. Given the increasing unrest among Negroes, King’s flare seems likely to spread a trail of little Birmingham’s through the nation during the next few months.”

He was out of his depth:

“King bears heavy organizational responsibilities, and it is in this realm that he is most criticized.”

He was immoderate:

“Seven leading Alabama churchmen, some of whom had staked their prestige and positions upon a moderate solution in Birmingham, had openly criticized [King’s] actions there. He answered them with a publicly released 9,000-word letter … [which] split him from the white moderates of the South and suggested that Negroes would plot their own course in the future.”

Martin Luther King Jr. might have looked threatening to white Americans in the early ’60s, even those that considered themselves informed and fair-minded. He appeared far more attractive in a short while, though, as angrier voices arose in the black community. When the Black Muslim church started gathering supporters and Black Panthers became active, Dr. King suddenly seemed extremely moderate, reasonable, and comfortable.

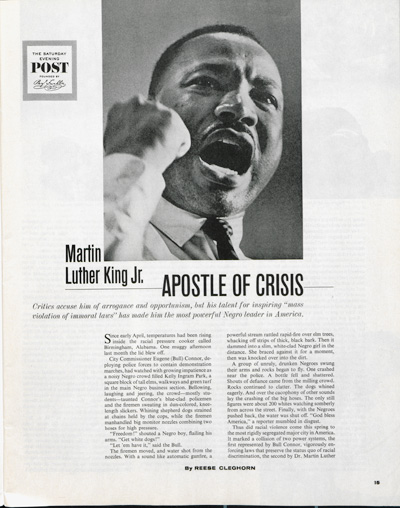

Overall, Cleghorn tries to be informed, but he was writing from a time when middle America still felt it had the luxury of disapproving and dismissing the voices of black America. Cleghorn does little to allay fears of future riots and racial violence. Even the chosen photograph seems to heighten the effect; you’d have to look long and hard to find a more menacing picture of Dr. King.

Click here to read Cleghorn’s original article from 1963 [PDF].

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Black America was so long

A blur kept in time and in place

By white America. This wrong

Of giving one’s rights based on race

At last focused in on one man,

Who gave a face to civil rights,

Who gave a dream for all time span,

Who brought together blacks and whites.

Doing his life work, Dr. King

Was loved and hated, praised and killed.

But a nation began changing.

His dream is still being fulfilled.

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day,

Reminder of a long, hard way.