On May 14, 1856, James King stepped out of his editor’s office at the San Francisco Bulletin and was immediately confronted by James P. Casey, editor of the San Francisco Sunday Times. The two exchanged a few words before Casey drew a pistol and shot King. The Bulletin editor fell, mortally wounded.

It was one of hundreds of murders that occurred that year in San Francisco, but it prompted an army of 3,000 armed vigilantes to seize power, and threatened to topple the state government of California.

San Franciscans had become accustomed to shootings, but King’s death was intolerable. The editor had earned a reputation in the city for his relentless attacks on government corruption and inaction. One of his targets was James Casey whom King had revealed as a former inmate at Sing Sing Penitentiary.

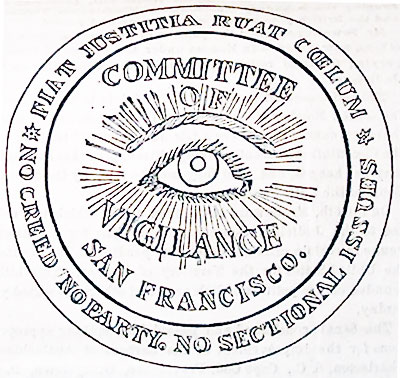

King’s followers expected Casey’s corrupt friends in the city government to secure his release from jail and protect him from prosecution. Consequently, they revived the Vigilance Committee, which had been inactive since 1853. The Post of June 21, 1856, picks up the story:

“On the 16th, Mr. King died, and the whole city became a scene of excitement. The old Vigilance Committee called a meeting, and placards of an inflammatory nature were posted up, calling upon the citizens to take the law in their own hands… On Saturday, the 18th, an organized force of 3,000 citizens, divided into division and companies, marched from the Committee’s rooms and took possession of the jail. They took from thence Casey and a gambler named Cory, the murderer of Colonel Richardson, and carried them to the Committee rooms, where they remained strongly guarded. … Both the prisoners, it is supposed, would be hung.”

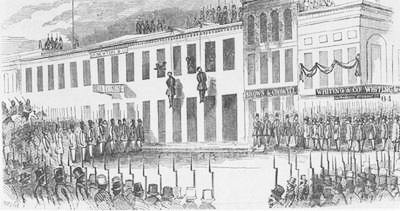

Which they were. The Vigilance Committee held a swift trial of both men and, five days later, hung them before a large crowd.

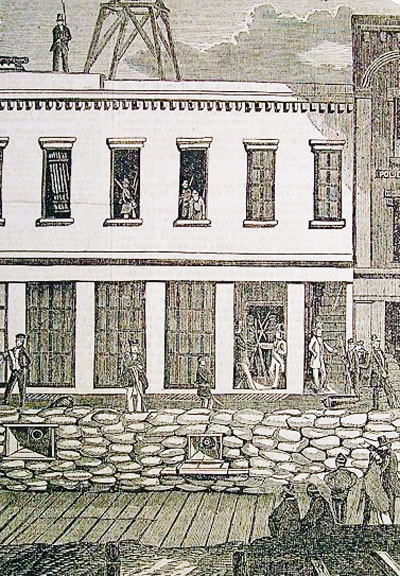

The Committee did not disband after this execution, but proceeded to arm itself, arrest questionable characters, and try them, completely ignoring the city’s police and courts. Fearing the governor would disband them by force, the Committee members fortified their offices and gathered weapons. Meanwhile, the governor’s political machine, calling itself The Law and Order Party, attempted to obtain weapons from Federal arsenals.

In August, a Committee member named Sterling Hopkins, attempted to arrest Rube Maloney, who was trying to secure Federal rifles from the local armory. David S. Terry, a judge on the state supreme court, and a man loyal to the state administration, was present. According to the Post of August 2,

“Judge Terry… interfered to protect Maloney, and, together with others, formed an armed party to escort Maloney to the [weapons at the] Dupont Street armory. Hopkins collected assistance, and attacked the other party in the streets. A struggle ensued, in the course of which Terry stabbed Hopkins with a Bowie knife.

“The news of the melee was communicated to the Executive Committee, who were in session, and the great bell was sounded for the rally of the Committee’s troops. In fifteen minutes a regiment of infantry, two companies of cavalry, and five companies of artillery were in motion.

“Maloney and his friends had taken refuge in a brick building, well guarded and fortified. This building was invaded on all sides by the Committee’s troops, and the inmates ordered to surrender. They obeyed without hesitation, and Maloney and Terry were… conveyed as prisoners to the headquarters of the Committee.”

The Committee then entered the armory, seized the weapons, and arrested the state troops, but released them on parole.

“On the same day Hopkins was stabbed, two vessels, freighted with arms for the State authorities were seized in the Bay by armed vessels, belonging to the Committee… [The] commander of one of these vessels, was arrested by the Federal officers, and held in $25,000 on the charge of piracy.”

The governor declared a state of insurrection and ordered a local banker and former artillery officer, William Tecumseh Sherman, to form a state militia. Sherman appealed to citizens to join his force, but gave it up after a week, when only a handful of men showed up.

The Committee tried Judge Terry but, to general surprise, acquitted him. Terry was freed, but resigned his judgeship in the state court.

In July, the Committee was roused to summary action again:

“Messrs. Hetherington & Randall, large real estate operators in San Francisco, doing business together, had a disagreement about pecuniary matters. They met on the 24th of July at the St. Nicholas bar. Hetherington commenced an assault upon Randall, and they fired simultaneously at one another—six shots being exchanged. Randall fell, mortally wounded. The regular police attempted to arrest Hetherington, but they were overpowered by the police of the Vigilance Committee, who hurried Hetherington away to their headquarters. Randall died the next day. Hetherington was tried by the Committee on the 26th, and hung on the 29th.

“Philander Brace, who committed a murder a year or two since, was hung at the same time. About fifteen thousand spectators witnessed the execution, and there were four thousand troops of the Committee present under arms. All the approaches to the place of execution were guarded by cannon.

“One of the most revolting scenes ever witnessed occurred at the execution. Hetherington proceeded to address the crowd, but was continually interrupted by the most disgusting profanity on the part of Brace, which at last proceeded so far, that it was deemed necessary to silence him by tying a handkerchief over his mouth.”

These executions seemed to dispel much of the passion for justice in the city. The Committee conducted an investigation of state corruption and, after publishing its findings, disbanded.

For all the weaponry it seized, the Committee’s action were generally bloodless. It executed only four prisoners and ordered over two dozen out of the state. Altogether, its actions were only a small part of the city’s mayhem: “There were 489 persons killed during the first 10 months of 1856,” the Committee reported. “Six of these were hanged by the Sheriff, and forty-six by the mobs, and the balance were killed by various means by the lawless element.”

In its earliest reporting, the Post was critical of the Vigilance Committee

“The Pacific State seems to be in a far from pacific condition. Two murders a day, we see it stated, is about the average for the past year. Criminals escape through the meshes of the law, and [lynch law] has to be appealed to—which, even when it does justice, does it unjustly.” [June 21, 1856]

If the state had become lawless and corrupt, the article asked, who was ultimately responsible?

“Evidently the majority of the people. They must be lacking either in the ability or the desire to choose the right kind of judges. In either case they are proving themselves incapable of self-government.”

But later that summer, the Post had become more sympathetic to the vigilantes:

“When ruffians… [grew] audacious in their villainy, no longer… content with pillaging the city treasury, but, trusting to the fact that their cronies occupied high civil and even judicial positions, [they] began to believe that they could knock down, stab and shoot peaceable and orderly citizens with impunity

“The great masses of society, including nearly the whole of the powerful middle classes, began to grow alarmed. And when they found that these gamblers, rowdies, and cut-throats were not trusting in vain in their political friends in high civil and judicial stations—then, as practical and justice-loving men, they felt that the time for resistance had come.”

Was it an insurrection, as the California governor claimed? Or the triumph of a law-abiding public? According to William T. Sherman, it was a pointless and dangerous exercise in mob thinking:

“As they controlled the press, [the Committee] wrote their own history, and the world generally gives them the credit of having purged San Francisco of rowdies and roughs; but their success has given great stimulus to a dangerous principle, that would at any time justify the mob in seizing all the power of government; and who is to say that the Vigilance Committee may not be composed of the worst, instead of the best, elements of a community? Indeed, in San Francisco, as soon as it was demonstrated that the real power had passed from the City Hall to the committee room, the same set of bailiffs, constables, and rowdies that had infested the City Hall were found in the employment of the “Vigilantes;” and, after three months’ experience, the better class of people became tired of the midnight sessions and left the business and power of the committee in hands of a court.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

We are much more men then you will ever be and we have a hell of a lot more balls than you Frank.

I suppose, once, real men had to have walked the land of Saint Francis. Apparently, however, they’ve not left much of a trace.

Know one thing, though: I’m getting mighty fond of poet, Ima Ryma. Got some stones.

I, City of San Francisco,

Warn those that think I’m just a wuss,

Where old hippies and far libs go,

That make me a pushover puss,

Look into my past history

When citizens had had enough,

Grabbing nasty powers that be,

Who after hanging weren’t so tough.

Vigilantes cleaned house before.

If pushed they will do so again,

If my citizens get so sore

With too much corruption and sin.

Let the scumbags suffer the fate,

All hang high from the Golden Gate.