The following is an excerpt from “The World Does Move,” from July 7, 1928 [PDF]. The author is listening to a judge’s outrage at the state of the nation’s youth.

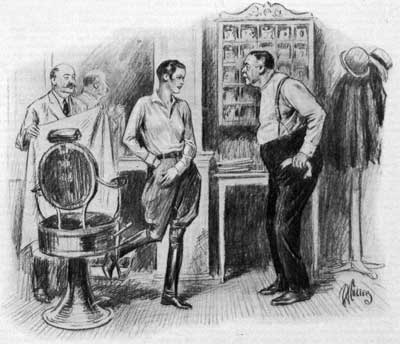

“I’ve been going to the same barber shop for fourteen years,” he said harshly, as I sat down. “I went to it for the last time today. I took off my coat and necktie the way I always do, and then I noticed there were three women sitting there in the waiting chairs and looking at me as if I’d committed a crime. Mad at me for taking off my coat and collar in a place where they had no right to be themselves! I thought probably they were them to solicit for a charity or something; but just then old George called ‘Next!’ And my soul, if one of those women didn’t get right up and march to the chair and sit down in it !

“That wasn’t the worst of it. The person that had just got out of the chair was wearing boots and breeches, but it wasn’t a man. It was a girl—one that had been a nice-looking girl, too, until she sat down in that chair and had three feet of beautiful thick brown hair out off. She was my own daughter, Julie, nineteen years old. I didn’t my a word to her—not then; I just looked at her. Then I told old George I guessed his shop was getting to be too co-educational for me and I put on my things and went out. I’ll never set foot in the place again!”

“Where will you get your hair cut, judge?”

“I guess we’d better learn to cut our own hair, we men,” he mid bitterly. “There really isn’t any place left nowadays where we can go to get by ourselves. Coming home from Washington the other day, I was in the Pullman smoker—what they call the club car — and I’ll eat my shirt if four women didn’t come in there and light cigarettes and sit down to play bridge!

Never turned a hair—didn’t have any hair long enough to turn, for that matter. They won’t let us keep a club car, or any kind of club, to ourselves nowadays;

they got to have anyway half of it.

“I said when we let ’em into the polling booth they’d never be contented with that, and I was right. Remember all the fuss they made about their right to vote? Well, they’ve proved they didn’t care about that at all, because more than half the very women that made the fuss don’t bother to vote, now they know they can. They just wanted to show as we couldn’t have anything On earth to ourselves. They haven’t left as one single refuge.

“It used to be a man could at least go hang around a livery stable when he felt lonesome for his kind; but now there aren’t any more livery stable. He can’t go to a saloon; there aren’t any more saloons. [Written in 1929, nearly a decade into Prohibition] Once he could go sit in a hotel lobby, because that was a he place; nowadays hotel lobbies are full of women sitting there all day. When I studied law there weren’t three women in all the offices downtown; now you can’t find an office without a bob-haired stenographer in it, and there are dozens of women got their own offices—every kind of offices.

“That’s another thing I’ve been having it out with Julie about. She’s not only cut off her hair; she wants to go into business as soon as she finds out what kind she’d enjoy most. She’s like the rest—the one thing that gives her the horrors is the idea of staying home.

“What’s become of the old home life in this country anyhow? Everybody seems to have to be going somewhere every minute. There’s the car in the garage: it’ll take us anywhere—let’s go! ‘Let’s go’ is the unceasing national cry.

“I understand there’s a great deal of what they’ve now invented a horrible new word for—’necking’ — while they’re on the road between parties and movies and end-of-the-night breakfasts. But it’s always, ‘Let’s go—let’s go anywhere except home!”

He paused for a moment, while his bushy gray eyebrows were contorted in a frown of distressed perplexity: then he looked at me almost with pathos and speaking slowly, asked a question evidently sincere: “Does it ever seem to you, nowadays, that maybe we’re all—all of us, young people and old people both—that maybe we’re all crazy?”

Read the full story, “The World Does Move,” from July 7, 1928 [PDF].

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Typos galore