The American hunger for liberty has never been fully satisfied. It led to a revolution and political independence in 1776, but it had continued to evolve. After freeing themselves from the British crown, Americans wanted independence from the wealthy landowners and from the government. They wanted liberty for women and minorities. They chafed at restraints, and pushed back at every law that would restrict their rights of property, speech, or lifestyle.

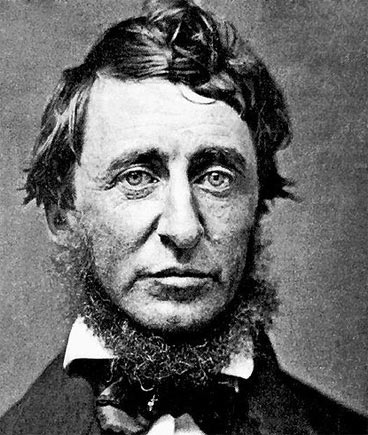

Henry David Thoreau is an unusual hero among the millions of freedom seekers in American history. He sought freedom not from government or capital, but from human nature.

He took his search for personal freedom to the wilderness in 1845, on July 4th — the significance wasn’t lost on him. That day, he moved away from home to live in the woods around Walden Pond, near Concord, Massachusetts. For the next two years, Thoreau tried to liberate himself from a life of distractions, comforts, and routine. As he put it: “I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

He declared an independence from society to pursue a life of simplicity and honesty. “Most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind.” He gardened. He wrote. He visited friends (he was living only 1.5 miles outside Concord). But he continued to reside in the tiny house for over two years. The account he wrote of his time there has changed many an American’s life.

In 1849, the Post reprinted a New York review of Thoreau’s lectures about his experiences.

A Young Philosopher Henry D. Thoreau, of Concord, Mass., has recently been lecturing on “Life in the Woods,” in Portland and elsewhere. There is not a young man in the land — and very few old ones — who would not profit by an attentive hearing of that lecture. Mr. Thoreau is a young student, who has imbibed (or rather refused to stifle) the idea that man’s soul is better worth living for than his body. Accordingly, he had built himself a house ten by fifteen feet in a piece of unfrequented woods by the side of a pleasant little lakelet, where he devotes his days to study and reflection, cultivating a small plot of ground, living frugally on vegetables, and working for the neighboring farmers whenever he is in need of money or additional exercise. It thus costs him some six to eight week’s rugged labor per year to earn his food and clothes, and perhaps an hour or two per day extra to prepare his food and fuel, keep his house in order, &c. He has lived in this way four years, and his total expenses for last year were $41.25, and his surplus earning at the close were $31.21, which he considers a better result than almost any of the farmers of Concord could show, though they have worked all the time. By this course, Mr. Thoreau lives free from pecuniary obligation or dependence on others, except that he borrows some books, which is an equal pleasure to lender and borrower. The man on whose land his is a squater is no wise injured or inconvenienced thereby. If all our young men would but hear this lecture, we think some among them would feel strongly impelled either to come to New York or go to California.

It wasn’t easy being Henry David Thoreau. He was a loner, a lifelong bachelor, an eccentric, and, at times, a contrarian who opposed the Mexican-American war and, with greater fervor, slavery. He died young, at age 44, from tuberculosis. His life was rough and irregular, but a rough passage is inevitable when you have to clear your own roads.

Thoreau would been quickly forgotten if he had not been championed by Ralph Waldo Emerson and his students. Walden was printed in small editions over the years. Scholars recognized it as a work of great talent, but not for another 40 years after Thoreau’s death. Its renown among American letters is only partly due to the endorsement of English professors. His lasting fame rests on his ability to address that American hunger for independence, as in “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”

My Life.*

by H.D. Thoreau

My life is like a stroll upon the beach,

As near the ocean’s edge as I can go;

My tardy steps its waves sometimes o’erreach,

Sometimes I stay to let them overflow.

My sole employment is, and scrupulous care,

To place my gains beyond the reach of tides;

Each smoother pebble, and each shell more rare,

Which Ocean kindly to my hand confides.

I have but few companions on the shore —

They scorn the strand who sail upon the sea;

Yet oft I think the ocean they’ve sailed o’er

Is deeper known upon the strand to me.

The middle sea contains no crimson dulse**,

Its deeper waves cast up no pearls to view;

Along the shore my hand is on its pulse,And I converse with many a shipwrecked crew.

* This poem, taken from Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, appears with the title “The Fisher’s Boy” in modern collections.

** “dulse”: a red seaweed that lives attached to rocks in deep water.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

We who love freedom share Thoreau’s strong desire to be left to the pusuit of our own moral ends–unimpeded by that most powerful and, because of its necessary “legitimacy,” dangerous threat to individual liberty, government.