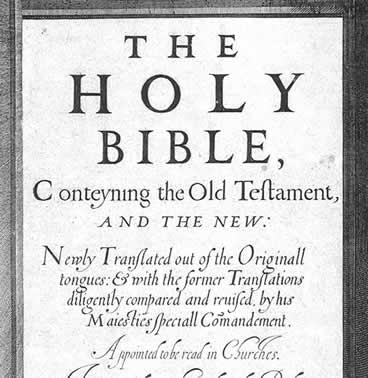

Since its publication 400 years ago this year, the King James Bible has become the most frequently quoted version of the Old and New Testament among English speaking people. Its style has become so widely accepted that many Christians have come to view other translations as flawed or even sacrilegious.

There are several reasons why Protestant Christians still rely on a translation made four centuries ago. There is tradition and familiarity. But there is also the power of the English language used in this work.

By good luck, or by the grace of God, King James commissioned this translation at a time when the expressive power of English was undergoing an incredible growth. As a 1951 Post article noted, the King’s translators proved highly creative in setting the biblical language of Aramaic and Greek into

the haunting phrases [that have] imprinted so deeply on the thoughts and imagery of all English-speaking people: “apple of his eye,” “powers that be,” “widow’s mite,” “filthy lucre,” “as a lamb to the slaughter,” “pearls before swine,” “worthy of his hire,” “broken reed,” “birds of the air,” “loaves and fishes,” “army with banners,” “clear as crystal,” “thorn in the flesh,” “still small voice,” “salt of the earth” —these are only a few.

The King’s goal was to produce a skilled, consistent, and rigorously edited version of scriptures (an earlier English translation of the Old Testament had included the commandment, “Thou shalt commit adultery.”) In the process, though, his scholars created a masterwork that influenced all writers of English for centuries. The power of its message, set to its best advantage amid the imagery and cadence of deathless poetry, could reach out beyond the faithful to touch agnostics and non-believers.

Abraham Lincoln is a good example. He openly challenged the teachings of the Christian faith as a young man. He firmly refused offers to pray with others. He purposely eliminated the word “God” from his speeches, preferring the ambiguous term, “Maker.” And he professed no faith in any life after death. Yet as the Post article, “How Well Do You Know the Bible?” notes, Lincoln might have been—

the President who read the Bible most in office was Lincoln; the White House guards used to find him, before he had had breakfast in the morning, turning the pages of his Bible in the small room he used for a library.

He had read the whole Bible and memorized long passages from it. Its words and phrases came frequently and effectively from his lips in speeches, political debates, and even casual conversation. Once, at a Cabinet meeting where his advisers were discussing the new greenback dollar bills that were issued during the Civil War, the question came up of what official slogan to print on them.

“In God we trust,” was suggested, but Lincoln had a more whimsical idea. “If you are going to put a legend on the greenbacks,” he said, “I would suggest that of Peter: ‘Silver and gold have I none; but such as I have give I thee,”’ quoting Acts iii. 6 verbatim.

Lincoln’s two greatest utterances, the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural, are filled with the rich word poetry of the King James Version, and we have the almost unanimous word of his biographers that he found the Bible his principal solace at a time when the nation he headed was undergoing its most terrible internal trials. In the summer of 1864, when he was living in a cottage at the Soldiers’ Home on the outskirts of Washington, a friend named Joshua. Speed entered his room unexpectedly and found the President sitting near the window, reading his Bible by the light of failing day.

“I am glad to see you so profitably engaged,” remarked Speed, with a touch of lightness. .

“Yes,” said Lincoln. “I am profitably engaged.”

“Well,” said Speed, “if you have recovered from your skepticism I am sorry to say I have not.”

The tall President rose from his chair, placed his hand on his friend’s shoulder, and looked him earnestly in the eye. “You are wrong, Speed,” he said. “Take all of this book upon reason that you can, and the balance on faith, and you will live and die a happier and better man.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Good article, Jeff. Our church-going readers will appreciate it. Thanks.