When war began in April, 1861, Northerners and Southerners alike were talking about a quick, glorious victory. Abraham Lincoln wasn’t among them. He knew, long before most Americans, that the war would be costly, long, and bitter. He also learned the pain and loss many Americans eventually felt when his friend, Elmer Ellsworth, was killed on May 23, 1861.

On that day, Colonel Ellsworth and his regiment were clearing out the Confederate troops in Alexandria, Virginia, right across the Potomac, within sight of the Capitol and White House. On June 5, 1861, the Post quoted from the Army’s official report:

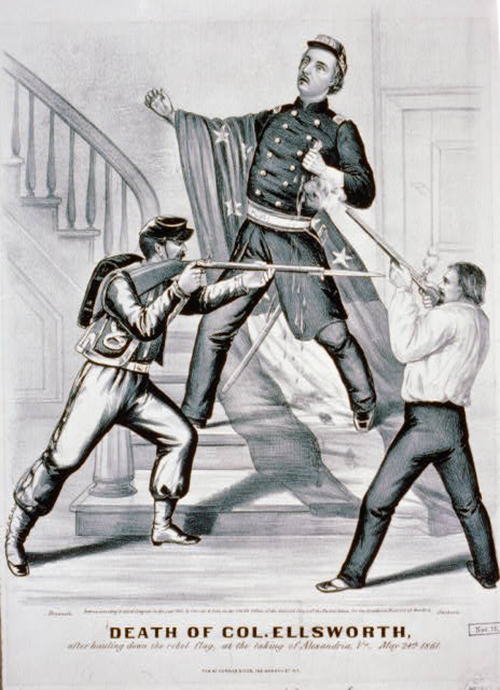

It appears that Ellsworth was marching up the street with a squad of men to take possession of the telegraph office, when, in passing along, he noticed a Secession flag flying from the top of a building. He immediately exclaimed—“That has to come down” and, entering the building, made his way up to the roof with one of his men, hauled down the rebel emblem, and wrapping it around his body, descended.

“While on the second floor, a Secessionist came out of a door with a cocked double-barreled shot-gun. He took aim at Ellsworth, when the latter attempted to strike the gun out of the way with his fist. As he struck it, one of the barrels was discharged, lodging a whole load of buckshot in Ellsworth’s body, killing him instantly. His companion instantly shot the murderer through the head with a revolver, making him a corpse a second or two after the fall of the noble Ellsworth. The house was immediately surrounded and all the inmates made prisoners.”

The remains of the deceased were brought over to the Navy Yard this morning. The doleful peals of all the bells in the city are announcing the sad news to the citizens. The President visited the Navy Yard and saw the remains of his friend Colonel Ellsworth.

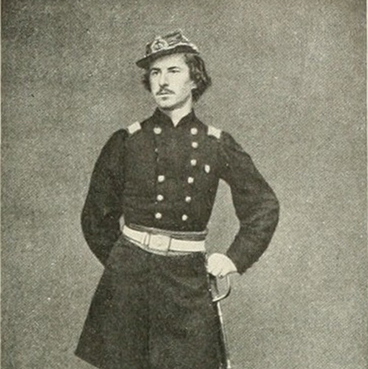

Like Robert E. Lee and Ulysses Grant, Ellsworth was a representative man of his time. While still a teenager, he left his New York home and travelled to the wilds of Illinois where he took several jobs, worked hard, and lived frugally. In the late 1850s, he was inspired to form an elite militia corps. Its soldiers would wear the distinctive uniform of the French Zouave soldiers, and would be trained for agility and strength. Each man would be moral, sober, and utterly dedicated to the corps and its training. Soon Ellsworth was travelling the country, putting on demonstrations and drill practices with his Zouaves before amazed and enthusiastic crowds.

But it ended when he struck up a conversation with Abraham Lincoln after a demonstration in Springfield. Elmer Ellsworth immediately hung up his fanciful Zoave uniform and disbanded the militia so he could became a law clerk at Lincoln’s firm.

Lincoln appears to have taken Ellsworth under his wing, encouraging him, inspiring him, and acting very much like an older brother. He probably recognized himself in this earnest young man who was taking the hard, solitary road to success. In turn, Ellsworth became devoted to Lincoln and, eventually, a valuable part of his presidential campaign. He followed him to Washington after his election and was a frequent guest at the White House. Then, in May, with a fresh commission from the president, Ellsworth marched off to his fate.

Washington, May 25— The remains of Col. Ellsworth were this morning conveyed to the East room of the White House, where they lay in state for several hours. The President and his family visited the remains and took a farewell look at the face of their much-loved friend, before the crowd was admitted.

Even Lincoln’s closest associates admitted that he rarely shared his thoughts or feelings. But on this occasion, he made no effort to hide his grief, as Senator Wilson of Massachusetts observed when he visited Lincoln on May 24.

As we entered the library we observed Mr. Lincoln before a window, looking out across the Potomac… He did not move until we approached very closely, when he turned round abruptly, and advanced toward us, extending his hand: “Excuse me,” he said, “but I cannot talk.”

We supposed his voice had given away from some cause or other, and we were about to inquire, when to our surprise the President burst into tears, and concealed his face in his handkerchief. He walked up and down the room for some moments, and we stepped aside in silence, not a little moved at such an unusual spectacle, in such a man and in such a place. After composing himself somewhat, Mr. Lincoln sat down and invited us to him. “I will make no apology, gentlemen,” said he, “for my weakness; but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in great regard. Just as you entered the room, Captain Fox left me, after giving me the painful details of his unfortunate death. The event was so unexpected, and the recital so touching, that it quite unmanned me.”

Ellsworth was honored as a hero, and the souvenir hawkers were soon busy.

The flags which Col. Ellsworth seized and carried, the oil cloth on which he fell, &c, have been divided, and the pieces are carefully preserved by curiosity hunters. A resident of Paterson, New Jersey, boasts of possessing and exhibiting a piece of cheese which the gallant Colonel had in his haversack!

For months, newspapers and politicians spoke the name “Ellsworth” to evoke the spirit of patriotism and sacrifice. It was soon obscured by the growing casualty lists and, by war’s end, was barely remembered, just one death among 600,000.

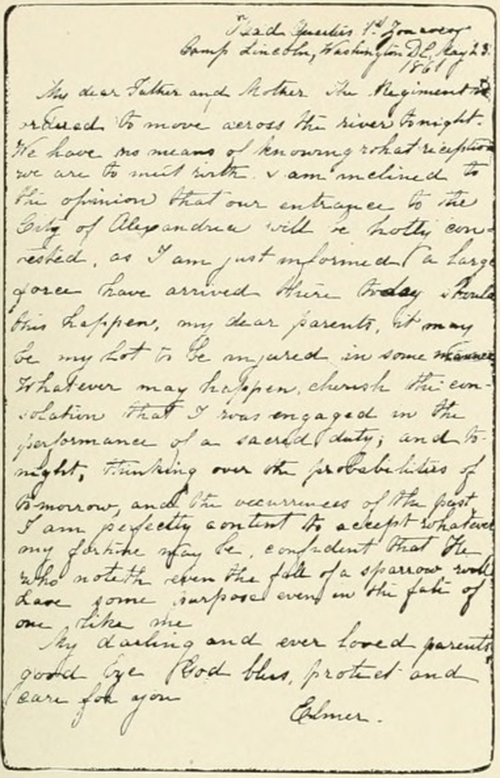

The Final Letter from Elmer Ellsworth

THE LAST LETTER— The following letter gives us a higher idea of Colonel Ellsworth than we previously had. We had looked upon him as a dashing, daring, but reckless and somewhat superficial soldier—this letter shows, however, both depth and nobility of character, and that he was at heart a religious and believing man. There is a tone of sadness in the letter, almost ominous of his approaching end;

Head Quarters, First Zouaves, Camp Lincoln:

Washington, D.C., May 23, 1861

My Dear Father and Mother—The Regiment is ordered to move across the river tonight. We have no means of knowing what reception we are to meet with. I am inclined to the opinion that our entrance to the city of Alexandria will be hotly contested, as I am just informed a large force have arrived there to-day. Should this happen, my dear parents, it may be my lot to be injured in some manner. Whatever may happen, cherish the consolation that I was engaged in the performance of a sacred duty; and tonight, thinking over the probabilities of tomorrow, and the occurrences of the past, I am perfectly content to accept whatever my fortune may be, confident that He who noteth even the fall of a sparrow will have some purpose even in the fate of one like me.

My darling and ever loved parents, good-bye. God bless, protect, and care for you.

Elmer

[Saturday Evening Post, June 8, 1861]

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I worked for him in Illinois,

And followed him to Washington.

With army troops I did deploy

To keep the rebels on the run.

I was returned a casualty.

In the White House I laid in State.

He came to bid farewell to me,

To mourn my consequence of fate.

He was but one man who yet must

Carry all the burdens of war.

I might have been his first loss thrust

On him, but he’d bear many more.

I called the President my friend,

And he wept for me at my end.