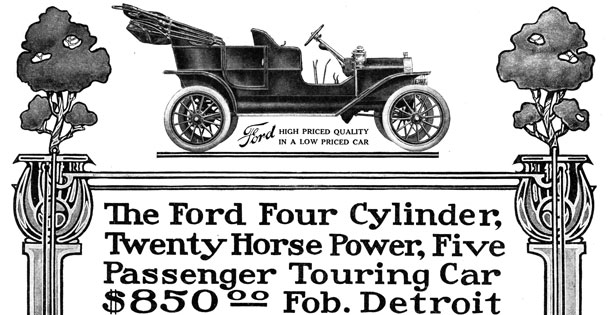

Shown below is the full-page advertisement seen on page 29 of the October 3rd, 1908, Saturday Evening Post. It appeared among ads for other, better known automobile makers like Packard, Cadillac, Winton, and Oldsmobile—expensive cars for wealthy buyers. Until then, the Ford Motor Company had been only a modest competitor, producing a small number of Henry Ford’s Model R and Model S vehicles.

But with his Model T, things would be different. Ford would introduce a new design and business plan with the assumption that all Americans, not just the rich, wanted their own automobiles. He was ready to give them—

a 4-cylinder, 20 horsepower, five-passenger family car—powerful, speedy and enduring,—a car that looks good, and is as good as it looks.

His gamble paid off generously; in the first year, Ford sold 10,000 Model Ts—ten thousand new cars for a nation that previously had only 100,000 registered vehicles!

The Model T’s success was due, in part, to its superior engineering, including its use of Vanadium steel, a tough, lightweight alloy that kept the weight of the vehicle down to 1200 pounds.

Not an ounce of necessary weight sacrificed, not an ounce of dead weight in the car.

But no selling point was more important than price; the Model T sold for just $850 (about $20,000 today). As Ford proclaimed:

this big, roomy, powerful five-passenger touring car … possesses at least equal value with any “1909” car announced, and at the same time sells for several hundred dollars less than the lowest of the rest.

Compare … the new Ford car with those of any higher priced car offered and see if you can justify … the additional expenditure that buying any other car involves.*

Ford’s Model T began several revolutions. Of course it changed manufacturing and business

methods. But his “car for the multitude,” as he called it, also revolutionized the nature of the American family and society. Middle-income families gained a new mobility and independence as well as new opportunities. Life would no longer center around the family hearthside and the neighborhood. Americans could now explore their country, escape their town or village, drive off to new opportunities, or follow their whim to speed down a country road.

Year after year, Ford compounded his success. His yearly production doubled and doubled again, from 20,000 to 53,000 then 94,000. By 1913, when production reached 225,000 Model Ts, he was turning out a new car every 3 minutes. Meanwhile, the price kept dropping, too; in 1916, he could afford to sell his car for just $360 ($7,000 today).

This productivity was only possible because of Ford’s assembly line, which—according to critics—forced workers into mindless labor at an inhuman pace. Furthermore, critics claimed, this mass-production culture was spreading across the nation along with the Model T. Americans were endlessly racing after dreams and living at a pace of life beyond human endurance.

Nonsense, Ford replied. In 1926, he defended the culture and production methods that the Model T had made possible.

There is [one] criticism that appears when modern industry is mentioned—the charge that machine-production methods, rapidity of operation, is responsible for the so-called killing pace of present-day life. In one breath industry is charged with making men stupid, and in the next with making men too nervously alert. Both statements cannot be correct.

How is one to reconcile the killing pace with the fact that the average of human life is lengthened year by year?

We live on a planet driving at terrific speed through space; is anyone nervously ruined by letting the earth carry him along? We are naturally habituated to the speed of the planet.

In just the same way, no one who is in step with the pace of industry is conscious of it. Irritation does not arise from the pull forward; it is in the pull back. Only those who try to check the pace of progress find our present gait distressful.

Our pace was made by ourselves. We are not forced to keep up with something superhumanly set for us. Man sets his own pace, and he can only do what is within the limit of his power.

The world is on the move and gives every evidence of an intention to keep moving and to hasten its pace. Viewed in the mass, the spectacle may seem feverish to those who are not a part of it. But from the point of view of the individual there is no sensation of being rushed. Rather the alert men and women of today are irritated by what is, to them, the slow gait of progress. Most of them are in a hurry to reach a better goal, and their ideas are becoming more and more definite as to where and why they are going. People are eager for the real education of experience. They are filled with creative curiosity.

The debate continued long afterward, and continues today. Does new technology make our lives both frantic and mind-numbing? Or does it bring into our lives new rewards and new possibilities? As in every revolution, both extremes come true.

(We can make that comparison today because automakers, in those ingenuous times, advertized their prices. So we know that, in 1909, a Franklin cost $3750; an Oldsmobile Roadster, $2750; the Winton Six, $3000; a Cadillac “Thirty,” $1400, and a Chalmers Detroit [which boasted they made only 9% profit on their cars], $1,500.)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

My wife and I sing about 100 concerts a year to senior groups who love the old songs. One such song we sing is to the tune of “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” The “revised” lyrics go like this (we don’t know the author, but one of our senior fans gave us these words and said they were popular back when):

“Let me call you Lizzie, I’m in debt for you,

Let me hear you rattle, like all good Fords do,

Keep your tail lights burning, and your headlights, too,

Let me call you Lizzie, I’m in debt for you.”

I got myself a Model T

To take the good Lord on the road.

I made the car a church to be

In rolling save the sinner mode.

Accessorized with steeple that

Would fold down, and an organ to

Add music to the fast format,

To crank the crowds as I drove through,

Spreading the word with zeal on wheel,

Sermonizing faith to inspire,

From my Tin Lizzie churchmobile,

With an occasional flat tire.

Lordy, Lordy. Lickety split.

Save more souls. Better step on it.

This was the year my father, Robert Larew, graduated from Marshall College. Wonder if Daddy got to ride in an automobile within that year….