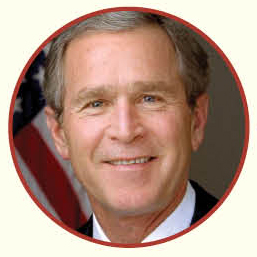

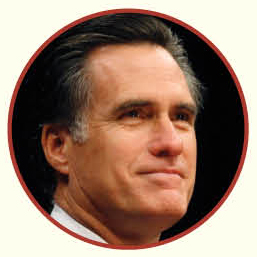

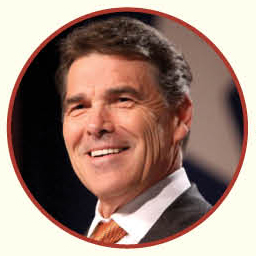

In the spring of 1935, at the depths of the Great Depression, Congress voted by a landslide to create Social Security—372 to 33 in the House and 77 to six in the Senate. Almost nobody was against it. In the years since, it has grown to be the biggest government program in history, anywhere ever, and arguably one of the most successful. It has lifted tens of millions of Americans out of poverty. Today it provides 56 million people a guaranteed paycheck, and nearly two-thirds of retirees count on it for more than half of their income. Yet many now see it as a huge failure. Among the 2012 presidential candidates, Rick Perry has called it a “Ponzi scheme” and a “monstrous lie,” and Mitt Romney has written that “to put it in a nutshell, the American people have been defrauded.” We are told it is going bankrupt. What happened? Where did Social Security come from? And is it really in such grave danger?

The story begins more than a century ago in Imperial Germany. In 1889 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck got a law passed setting up an old-age insurance program that required German workers to contribute a portion of their wages to a fund that would pay them in their retirement. Why? In a time of frightening worker unrest and socialist ferment, Bismarck bluntly admitted that he wanted “to bribe the working classes … to regard the State as a social institution … interested in their welfare.” In other words, he feared he had to start doing more for the workers or they might rise up against him.

Before long other European nations followed. The U.S., with its powerful spirit of self-reliance and independence, did not. Yet old age was getting harder for Americans. By the end of the 19th century the nation had gone from mainly agricultural to industrial, from rural to urban, and from extended families in which generations stayed together to what we now call the nuclear family, of parents and children alone. Americans who worked in factories or offices could easily find themselves out of a job in economic hard times, and when they retired they couldn’t fall back on their families as their parents had. Also, people were living longer. That all added up to more and more people facing long old ages without any resources.

A timeline of Social Security

Click on the arrows or dates to scroll through key moments in this interactive timeline.

- 1889

- 1933

- 1934

- 1934

- 1935

- 1940

- 1941

- 1944

- 1950

- 1956

- 1961

- 1972

- 1977

- 1983

- 1993

- 2000

- 2005

- 2008

- 2010

- 2011

- 2011

- 2011

European inspiration

German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck passes an old-age insurance program that becomes a model for Britain and other European nations.

An early American plan

Retired doctor Francis E. Townsend devises a program—funded by a two percent national sales tax—that would pay every American over 60 a pension of $200 a month that had to be spent within 30 days.

Protection for all

Louisiana Governor Huey P. Long launches the Share Our Wealth Society, which calls on the government to guarantee every family an annual income of at least $2,000.

Talks grow serious

Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins heads a committee that recommends a federal social insurance plan, which includes unemployment insurance and “old-age” security.

The beginning

Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act on August 14. Payroll taxes are first collected in 1937.

MONTHLY PAYMENTS start

On January 31, Ida May Fuller becomes the first to receive a monthly check. The amount is $22.54.

The guarantee

President Roosevelt is quoted as saying: “We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my Social Security program.”

The program grows

Mary Thompson, a widow, is the one millionth Social Security recipient.

Inflation, duly noted

Social Security adds a cost of living adjustment.

Help for the disabled

Social Security is amended to provide monthly benefits to disabled workers ages 50 to 64 and for disabled adult children.

An early retirement option

President Kennedy signs an amendment permitting men to retire at 62 with a reduced benefit. (Women had been given this right in 1956.)

A better inflation plan

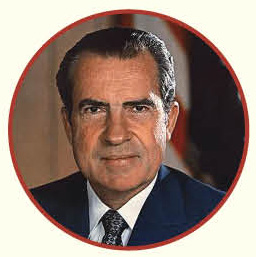

President Nixon signs an amendment to make cost of living adjustments automatic.

First fears of insolvency

Legislation is enacted to raise taxes and scale back benefits.

Money worries continue

President Reagan signs a law taxing benefits. The retirement age is raised from 65 to 67, but not until 2000.

Still more concerns

The taxable portion of benefits is raised from 50 percent to 85 percent.

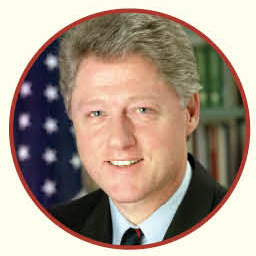

Staying on the job

President Clinton signs a bill eliminating the Retirement Earnings Test (RET), allowing seniors who continue working to receive full benefits.

The privatization effort

After winning re-election, President Bush uses political capital to push for partial privatization—a program in which individuals would manage their own accounts. In the face of resistance from seniors and their advocacy groups, the plan slowly dies.

Generation Shift

Kathleen Casey-Kirschling, generally recognized as the first-born member of the baby boom generation, receives her first Social Security check.

A new insolvency threat

The U.S. Deficit Commission, set up by President Obama, recommends raising the retirement age to 68 and reducing the annual cost of living increases. The plan is not adopted.

The Challenge

“There are one of two ways you can make Social Security work forever. One is to raise the retirement age by a year or two. The other is having slower growth in inflating the benefits of higher-income of Social Security recipients.” —Mitt Romney

An outright attack

Republican presidential primary candidate Rick Perry calls Social Security a “Ponzi scheme.”

Drawing a line in the sand

“We should … strengthen Social Security for future generations. And we must do it without putting at risk current retirees, the most vulnerable, or people with disabilities; without slashing benefits for future generations; and without subjecting Americans’ guaranteed retirement income to the whims of the stock market.” —President Obama, State of the Union

Click Arrow For Previous Event

Click Arrow For Next Event

There were modest pensions for veterans and a few company pension plans, especially among railroads. After the Stock Market Crash of 1929 a few states tried to set up old-age pension systems, but didn’t have the power to effectively implement them. Most older Americans had nothing to fall back on. By 1934, it is estimated, more than half of the elderly in the U.S. were unable to support themselves.

Popular movements arose to challenge this dire situation and agitate for impossible solutions. Huey P. Long, then governor of Louisiana, started the Share Our Wealth Society, which called on the government to guarantee every family in the nation an income of at least $2,000 a year (about $33,000 today), plus a pension for everyone over 60 and confiscation of every personal fortune above $8 million. By 1935 Share Our Wealth had 7.7 million members. Francis E. Townsend, a broke 66-year-old retired doctor, launched a proposal in 1933 to pay every American over 60 $200 a month ($2,400 today) on the condition they spend the money within a month. The payments would be funded by a two percent national sales tax. He soon had millions of followers who organized Townsend Clubs across the country to promote his plan.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt said at one point, “The Congress can’t stand the pressure of the Townsend Plan unless we have a real old-age insurance system, nor can I face the country.” So, on June 8, 1934, he sent Congress a message urging it to enact “social insurance … to provide security against several of the great disturbing factors in life—especially those which relate to unemployment and old age.” He added that “lessons of experience are available from states, from industries, and from many nations of the civilized world.” He set up a committee of five cabinet-level officials headed by Labor Secretary Frances Perkins to come up with a plan.

The committee soon had a large staff and an array of subcommittees. The five officials divided their job into three parts, with one big group tackling unemployment insurance, one big group working on health insurance, and a much smaller group focusing on old-age security. The unemployment team bogged down in disputes, and the health care reformers were kept from doing much by opposition from the American Medical Association, which didn’t want doctors restrained by national regulation. The old-age group, however, came together on a plan where workers and their employers would each contribute, paycheck by paycheck, to a fund that would provide the workers a pension after they retired. It was a relatively moderate, conservative answer to the radical ideas of people like Long and Townsend.

At first the proposed Social Security law was attacked by liberals as doing too little and by conservatives as approaching socialism; but opposition faded, and President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act of 1935 on August 14 of that year. The law included unemployment insurance, aid to dependent children, and other elements, but its biggest feature was the old-age part we now think of as Social Security. Taxes for it were first collected in 1937, and for three years the trust fund was built up before the first monthly Social Security check was written in 1940, giving Ida May Fuller, a retired legal secretary in Ludlow, Vermont, $22.54.

The idea was not to provide a pension where people would always get back the amount they put in; rather it was to collect a pool of insurance money from people and return it to them if and when they needed it. Thus what you receive depends on when you stop working, and a disabled worker can start collecting early and end up getting more than that worker paid in. Originally the law required you not to work at all after 65 to get Social Security no matter how much you had paid in. This requirement was intended to remove older people from the labor pool, creating more jobs for the young. The law also excluded farm and transient workers, domestic servants, and anyone working for someone with fewer than 10 employees. Those people may have needed Social Security the most, but legislators believed the tax would be too hard to collect from them.

The system has been modified and expanded many times since its creation. In 1940 benefits were added for a survivor of a retiree who died. In 1950 cost of living raises were introduced. Disability coverage was added in 1954. Also, Medicare and Medicaid, begun in the 1960s, are both officially part of the Social Security System. In the 1970s fixes started being made to keep the system from losing money; in 1977 the tax rate was slightly increased and benefits were slightly reduced, and in 1983 the retirement age was raised (to eventually reach 67 for full benefits) while the payout for early retirees and people still working was reduced.

Because the nation is going through an enormous demographic change with aging baby boomers, none of those adjustments has made the system permanently sound. There are now more Americans over 65 than ever before to take money out of the system and not enough younger workers paying in to keep up. Social Security’s financing is in need of repair. Nonetheless, the system is hardly on the brink of collapse, as some claim.

Around 56 million Americans, a sixth of the population, received Social Security benefits in 2011. The system is paying them a total of $727 billion. After years of taking in more than it paid out and building up a surplus, the system has just begun to dip into that surplus—the “trust fund” of government bonds, now at a peak of $2.6 trillion. No one can say exactly how fast the trust fund will diminish, but the Social Security Administration and the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) both estimate that if nothing is done it will last until around 2036. But even in that extreme case, Social Security will be able to pay out as much as it takes in. It just won’t be able to pay recipients 100 percent of what they get now; instead, they’ll get something like 76 percent.

How can the loss of money be stopped? There are four possible ways: raise the retirement age; reduce benefits or cost of living increases; raise the top income level for paying Social Security taxes; or raise the Social Security tax rate. If the tax rate were raised from its present 12.4 percent, half paid by employees and half by employers, to 14 percent, that would do it, according to the CBO. More likely is a mix of a smaller tax rise, a modest increase in the retirement age, and a rise in the cap on taxed salary.

In other words, Social Security has very real long-term funding problems, but it is not in a crisis that can’t be fixed. And as for those who say that its trust fund doesn’t really even exist because the government has spent all the money in it, in a sense that’s true—but it’s not a very meaningful sense. The trust fund’s money is all in government bonds, which pay an average of 2.76 percent. Any bond is, in effect, a loan of money to the bond’s issuer and only has value if the bond issuer can repay the loan. The bonds that compose the Social Security trust fund are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S., and it is almost universally agreed that the U.S. government is more dependable than any other issuer of bonds—or any other investment—on Earth. So the Social Security trust fund may not be 100 percent safe, but any other conceivable investment is probably less safe. That’s one reason why attempts to “privatize” Social Security—replacing the trust fund with individuals’ investments in stocks and other securities, such as President George W. Bush proposed in 2005—haven’t gone very far. After the recent stock market crash, privatization appeals to fewer people than ever.

And here’s a glimmer of good news in that long, uncertain future: Eventually, the flood of baby boomers will end, and older people won’t so greatly outbalance younger ones as they do in this unique period of history. So even if the next generation can’t retire quite as comfortably as Americans could in the unprecedentedly prosperous years since World War II, maybe the generation after that will be more comfortable again—as long as we don’t give up on a Social Security system that has worked wonders for millions of Americans for most of a century. There’s a reason it has been “the third rail of American politics” ever since House speaker Tip O’Neill first called it that in the 1980s: Everyone worries about it, but virtually no one wants to lose it.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Social Security is broke. The full faith of USA backing behind SS is no different than the backing behind any other of our national debts. For several months now SS has been paying out more than it has taken in. This deference will now increase exponentially into the future. The deficit is now financed by interest from the bonds in the SS fund. The actual dollars used to make up the deficit are freshly printed just the same way as payments to any of our other deficits. So if SS is not broke because of the bonds that pay 2% interest in the SS fund, why not just print up enough bonds so that no one will even have to pay into SS any more. As a matter of fact I suspect that these bonds even exist. More likely this SS fund is just a number in a ledger somewhere. At some point in the future the books will have to be balanced. No amount of “fairness” will pay off our deficit. The only solution is the same one that all governments have used in the past, inflation. So all you other SS recipients, if we believe this story and let this thing happen, we are getting what we deserve.

Besides stealing all the money out of our Social Security Trust Fund the politicans in Congress have,over the years,increased the Federal tax codes from about 30 pages in 1913 to 5,296 pages in 2011. These added tax codes are riddled with loopholes to benefit big business and the rich. Now you know why our government is broke and is about 15+ trillion dollars in debt. All the politicans blame Social Security for causing a budget imbalance. For the life of me I can never understand why they keep using Social Security as a scapegoat. Everything they do in Congress is done along party lines to enhance their one sided agenda. How about “DOING THE RIGHT THING” for the good of the people who sent you there to represent us and not your political party or your loophole contributers to your re-election fund.

I HAVE TO AGREE WITH THE PREVIOUS COMMENTS RE: CONGRESS STEALING FROM SOCIAL SECURITY FUNDS. ALSO, WHAT ABOUT THE UNFORTUNATE PERSONS WHO DIE AND DO NOT DRAW BUT MAYBE TWO MONTHS OF S/S. THE SURVIVOR MAY (OR NOT) DRAW AT MOST HALF OF THE AMOUNT THAT WOULD HAVE GONE TO THE EARNER. THERE ARE TOO MANY UNQUALIFIED ILLEGALS ON THE PUBLIC DOLE, SOCIAL SECURITY SHOULDNT BE AN ISSUE. IT WORKS. THANK YOU, Helen M Swope

Social Security is my absolutely only income. I have no other income of any kind. I don’t own any property and I don’t have any savings. I have to live

completely on my Social Security. I really don’t think I have to worry about losing it, however, because I’m 84 years old. The information in this article is very interesting. Thanks.

Evelyn Long

Social Security was a solvent company until all the leaders of our nation started to drain it, by funding other causes and slowly depleating it. By now it should of had trillions, instead we have an almost bankrupt fund that could have kept all the people who put their hard earned money into it not having to listen to yearly woes of how we are going to save it. Here’s a great idea, start repaying Social security back all the money that was taken from it with interst. Oh wait, they can’t do that their still taking from it. Sorry, my bad

If Congress hadn’t dipped into the social security fund for other things social security probably wouldnt be broke. Frankly, I think we should have every one should have health care benefits. By putting an extra percent onto the taxes it would probably pay for it. Canada, France Belguim, Germany and other countries have it, why can’t the U. S.