The recent passing of Dick Clark reminded us of the early days of rock music—back when it was alternately called “rock and roll” and The End of Civilization.

Though we remember Clark as a perennially nice, inoffensive guy, he was a force for change in the ’50s. Not only did he play the teen music that parents disliked so much, he insisted on welcoming black teens into his studio audience, and traveling through the South in a racially mixed tour. His “Caravan of the Stars” bus was often denied service and even threatened by armed segregationists.

Just as significant, though, was his promoting of rock ‘n’ roll, which helped integrate black and white traditions and audiences.

When it emerged unexpected in the 1950s, many Americans were shocked and suspicious of this strange, energetic new sound.They were accustomed to “pop” music. But rock ‘n’ roll was, in fact, true “pop” music if the word is meant as an abbreviation of “popular.”

Up to that time, the musical tastes of Americans had been largely shaped by a big industry with a few record labels, which determined much of the music America heard.

As a 1959 article reported, however, the predominance of these companies fell when a few small, independent studios, with little budget and no advertising, produced enormous hit records.

Up until a few years ago there was a fairly orderly sequence that took place in the launching of a new “pop” record. Everything was done big. Whenever one of the major recording companies came across a catchy tune, the company assigned it to a big-name singer, backed him up with a big-name band, then unleashed a barrage of publicity.

Today the popular-record business… is dominated by the smalls and the unknowns.

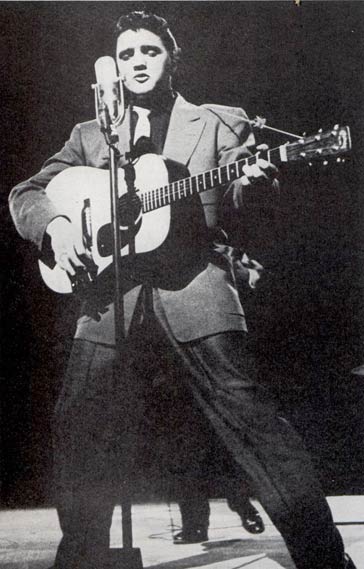

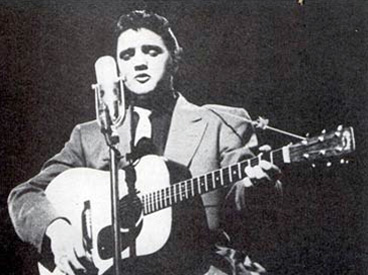

Knowledgeable men in the field agree … the record revolution started on a hot day in 1953 when a slim high-school boy, with his hair nearly down to his shoulders, fidgeted with a beat-up guitar below the windows of the newly opened Sun Recording Studios in Memphis, Tennessee.

The boy, who had taken time off from his after-school job at the Crown Electric Company, spent an hour of indecision out on the sidewalk before he got his courage up and walked one flight up to the small one-room studio. When Sam Phillips, [Sun’s] owner, approached, the boy gulped and said, “Please, mister, I’d like to make a record for my mother.”

“Sure, buddy, just relax and we’ll give it a try,” Phillips said encouragingly.

Phillips was impressed, “the boy was just a raw kid with no training, but he had an interesting sound.” Phillips eventually found the “right song” for Presley —“Without Love.” As Phillips told the reporters, they “had to work hard to get the best out of his style”.

And even when we got something that sounded right, we had a terrible time getting any disc jockey to play it. The only place we got his records played at first was in the Negro sections of Chicago and Detroit and in California.”

But the sound eventually drifted into the hearing of America’s teenagers, where it struck a resounding chord.

After Presley’s overwhelming success [selling 35 million records by that year], unknown studios and artists were eager to try their luck, completely bypassing the big record labels.

Buddy Holly was another star-out-of-nowhere. Throwing together a few songs with a combo he’d assembled in Lubbock, Texas, he drove with his band—The Crickets—out to a tiny recording studio in Clovis, New Mexico—as far from the heart of the recording industry as you can get in the lower 48 states. By the time of his death, 30 months later, he had sold 6 million records—most of which had been recorded in the shadow of the big grain elevator in ‘downtown’ Clovis.

[Inspired by these successes,] youngsters with dreams of glory and gold pooled their talents. A singer would write his own song, hunt up a couple of instrumentalists, and they’d bang out tunes in rumpus rooms, living rooms or basements until they had something they thought was worth recording. Then they’d try to peddle their tapes. If a producer thought they had a “sound,” some unusual quality, either instrumental or vocal, that might drive the teen-agers wild, he’d take a gamble and make records.

This pattern, repeated over and over, revolutionized the popular-record field.

Today 70 to 80 per cent of the hits are being turned out by youngsters you never heard of a month or two ago, and who may disappear from the public scene just as abruptly as they came.

The major companies [are]… still turning out many records, but their hits don’t come as easily as they used to.

The biggest [obstacle] is the inflexibility of the major record companies. The independents are able to adapt quickly to any shift in teen-age tastes; the big organizations, saddled with protocol and chains of command, can’t move as fast.

Many record companies have found, too, that it’s a risky business to buy a new hit and re-record it with big-name singers and musicians. The teen-agers almost always prefer the original recording… [they] refuse to be impressed by the big-name approach.

As the early sounds of rock music poured out of teenager’s radios and record players, adults who were accustomed to ‘big name talent’ (Tony Martin, Jo Stafford, Kay Starr) created their own ‘new sound’: a strident, continual chorus of complaints about that ‘gawdawful music.’

As the Post authors noted, their criticism could actually ensure the survival of rock ‘n’ roll.

According to many teenagers, rock ‘n’ roll never would have got as popular as it is if their elders didn’t hate it so violently. It’s something to think about. The young parents of today compose the generation that went all out for swing against the noisy objections of their parents; and their parents used to get all giggly over ragtime. And so on and so on, back to the day some Neanderthal father listened in outrage as his son got off some hot licks with matched dinosaur-bone drumsticks on the family tom-tom. It must have seemed to that early man that the kids were going absolutely to the dogs.

Today the budding Elvis or Buddy doesn’t even need a small-town recording studio. They can put together their own hit in front of their computer, launch it on YouTube, then sit back and wait for the agents and record companies to show up.

The no-studio viral-marketing approach might have given us Justin Bieber, or any number of other rising artists you don’t like, but if the music industry was still controlled by a few record labels, we might still be listening to Frankie Laine and Rosemary Clooney.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

In Philly in the fifties ’twas

A time and place to sing and dance,

Breaking old barriers because

Dick Clark, one show, just took the chance,

On American Bandstand, to

Let a teen kid of color rate

A record for T.V to view –

A first that could bring a dire fate.

The kid said it had a nice beat

And was easy to dance to, so

That was that, and there came no heat.

All rocked and rolled on with the show.

Music makes lots of joy and fun

For all to sing and dance as one.