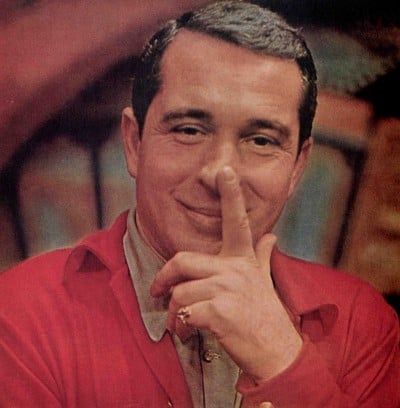

Changing the subject, I said, “I understand that there are people in TV production who are known as ‘screamers’ because they blow their tops and scream at everyone who’s rehearsing with them. On the contrary, I’ve heard that your idea of getting real mad when people goof is to reprove them by saying, ‘Please, fellows!'”

He said, “I’m afraid that’s a slight exaggeration. Things can get a little touchy with us, as with any other show, and there are times when a bit of sternness is helpful.”

“But you don’t scream,” I said.

“It’s not screaming,” he told me. “It’s more of getting things off my chest, and everybody else’s chest, instead of letting people mope and sulk, I believe in getting problems out in the open. There have been occasions during our rehearsals when things got a little hot and people did begin to scream.” He smiled his slow smile. “But I can put a stop to that in five seconds.”

“How?” I asked.

“I just remind them who the boss is,” he said. “It’s that simple. We once had a producer who could scream it up pretty good, but he did it only once or twice, no more. There’s bound to be tension built up when people work together on a stage, but there’s nothing worse than pushing a panic button in the control room and starting to yell at everybody. That only builds more tension, I think it happens because somebody is trying to prove that he is producing. After all, we’re all pros—we all know our jobs, I sing a little, the dancers dance, the band plays, and there’s no need for any hollering when somebody is telling you how to take your position and how to do what you’re being paid to do. If we don’t know that much, we might as well call the whole thing off. When it does happen, I simply calm the guy down by telling him not to do it again. When someone starts getting loud and unpleasant, it just builds tension, which I have to break down. Sometimes I get pretty idiotic up there trying to dispel it.”

“How do you do it?” I asked.

“One way is to foul everything up on purpose. For example, I’ll sing in the wrong key. That breaks the tension real quick. I’m determined that we mustn’t have it when we go on the air. Sometimes a number goes wrong, or a dance number is sour, or a song is bad—so what? Nobody’s going to send us to the electric chair for that. Anyway. I won’t stand for rudeness. We’ve had to let a couple of very good technicians go because of that weakness, although one of them I liked very much.

“I don’t mean that to get along on our show a person has to be a namby-pamby. I want people to be firm when firmness is needed, but not as a means of demonstrating their importance. On the other hand, I don’t like the kind who just amble along, not knowing who’s on first and who’s on second. When our show’s on I like to feel there’s somebody in the control room who has the reins firmly in hand and knows where he’s going. But I want him to do his job quietly and without a lot of fuss.

“We have an associate producer in our office, Henry Howard, who’s been with me for five years. You never bear him, you never know he’s around; but if something needs to be done, you can bet your life it’ll be done. Once you tell him something, you can forget it. And I don’t have to go to him every day and say, ‘Gee, you’re swell,’ He’s an adult. If he wasn’t handling his job, he wouldn’t be here. However, I want to be fair about it. It is not always a symbol of immaturity if somebody has to be told he’s good. A lot of grown-up people need it as food for their starving and undernourished egos.”

“I’m afraid I’m that way,” I confessed. “When I played football in high school, if the coach came up and shook me by the hand after a game, I was willing to go out there and die for him the following Saturday.”

“I don’t say you have to ignore such people,” Como went on. “But there are ways of showing them that you appreciate them without going all flowery and drooly. I know I don’t like that. If somebody comes up to me and gushes, ‘Gee, you sang swell tonight,’ I want to vomit. My instinctive reaction is, What else? After all, I’m getting paid for it. I’m supposed to be singing good. Not that I always do. Some nights when I open my mouth, nothing much comes out. But getting back to my point, I don’t want people patting me on the head for doing my job.

“Mine is a family-type show,” Como said, shifting the subject a bit. “I’m not ashamed of that, I’m proud of it. But it reminds me of a little story about the time when Julie London was on our show. The story also involves our costumer, a Japanese girl named Michi. A lot of girls figure cleavage is a great thing to have—if they have it. It is a part of being glamorous. So if I don’t watch the well-constructed girls like a hawk, we get beefs about their low necklines from the letter-writer-inners. One of Michi’s jobs is to watch our cleavage pushers.”

“Where did Michi learn to be a costumer?” I interrupted.

“She’s a beautiful girl,” Como told me. “A really lovely creature. She was going to school in this country, and she kind of fell into dress designing and from there into the costume business. It is her job to see that the girls on our show are dressed so that we don’t all get arrested. Once in a while in a rehearsal some girl will come out with too much of herself exposed for safety. When that happens, I throw my head back, open my mouth and howl, ‘Michi!’ The whole place breaks up, and Michi comes running and tucks lace and tulle in strategic places. One night when Julie London came on, I took one look at her and howled for Michi. Julie expressed herself very forthrightly about it, and she had every right to say what she did.

“She said, ‘Why don’t you hire boys to do your singing and dancing if that’s the way you feel?’ Julie is a gifted singer, a good performer and a good trouper, and in the end we settled it this way: ‘Personally,’ I said, ‘I like girls, but let’s not overdo it on TV; because if we do, the writer-inners are going to climb right up my back.’ I wasn’t kidding. They really do!”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

A very nice article.I am sad that Perry Como is so underrated.Not producing scandals ,headlines in the tabloids and showing of is obviously the way to get forgotten.

Best regards

G.Bendel

Germany

Wonderful article. I remember listening to Perry on the radio with my Mother. I have many of his records.